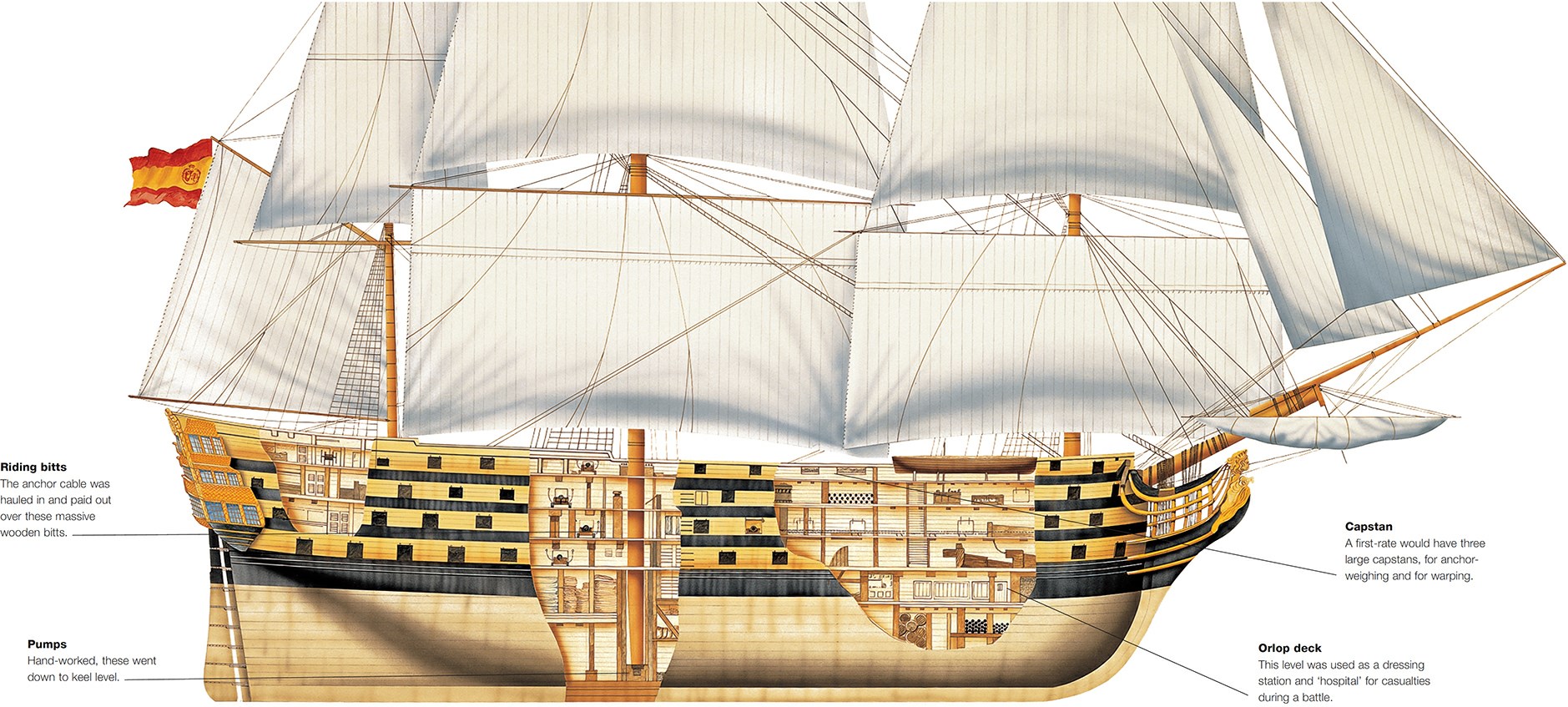

Epitome of the first-rate ‘ship of the line’, Santísima Trinidad was

designed to lead a fleet into battle and to withstand a heavy cannonade. The

concept of staying-power in the face of gunfire was becoming increasingly

important.

These eighteenth-century scale drawings are guides to the installation

of the supports for a canvas roofing to cover the entire upper deck. They were

made before the vessel’s conversion to a four-decker.

The largest warship of the eighteenth century, with four

decks of guns, the Spanish flagship was engaged in two of history’s great naval

battles, at Cape St Vincent and Trafalgar. It was known as the ‘Escorial (royal

palace) of the Seas’.

The Royal Shipyards at Havana, Cuba (then a Spanish

possession) were a major building site for warships. Costs were less than in

Spain and there were large timber resources, especially of hardwoods not

available in Spain, like the American cedarwood used in Santísima Trinidad. It

was the seventh Spanish warship of the name, confirmed by a royal order on 12

March 1768. Its designer was the King’s naval architect Matthew or Mateo

Mullan, an Irishman, and building was supervised by his son Ignacio.

It was launched as a three-decker of unusually large

dimensions. Spanish shipbuilding was of high quality, perhaps the best of any

nation. The ships were strongly built and generally of larger size for their

gun-rating than British vessels, which made them both more stable as

gun-platforms and better able to withstand attack.

A Spanish 70-gun ship was about 1540 tonnes (1700 tons)

compared to the 1134 tonnes (1250 tons) of a comparable British ship. This

tradition of size and strength gave the builders of 1769 confidence to

construct the largest warship of the time. Ships of this size were rarities: between

1750 and 1790 the British Navy had only six ships of 100 guns. The French also

built a few very large ships. In 1788 the French Commerce de Marseille exceeded

Santísima Trinidad in size, being 63.5m (208ft 4in) long, with a beam of 16.6m

(54ft 9in), but carried fewer guns, 118 on three decks (captured by the British

in 1793, it was broken up in 1802), and Océan and Orient, of 1790 and 1791,

carried 120 guns.

Years of action

In its first years the ship was probably not in commission

but held in readiness. With the declaration of war by Spain on Great Britain in

July 1779, it entered service as flagship of the Spanish fleet, under Admiral

Luis de Cordoba y Cordoba, operating with allied French ships in the English

Channel and the western approaches. In August 1780 it led an action which

resulted in the capture of 55 British merchant vessels from a convoy. In 1782

it participated in the second siege of Gibraltar, as flagship of a combined

fleet 48-strong of Spanish and French ships, but failed to intercept a British

relief convoy.

Increased firepower

In 1795, in a bold enhancement of its gun-power, a fourth

deck was installed, joining the forecastle to the quarter-deck and raising the

number of cannon carried from 112 to 136. This made Santísima Trinidad by some

way the most heavily-armed ship of its time. Back in service in 1797, it was

the Spanish flagship at the Battle of Cape St Vincent on 14 February, and

suffered major damage, partially dismasted and with over half the crew killed

or wounded. Santísima Trinidad struck her colours to HMS Orion, but before the

British could take possession, they were signalled away, and the ship was

rescued by Pelayo and Principe de Asturias, and limped back to Cadiz for

repair.

Particularly after the construction of the fourth deck,

giving the ship a very high freeboard exposed to sidewinds, Santísima Trinidad

did not have good sailing qualities and gained the nickname ‘El Ponderoso’.

Unlike contemporary French and British naval ships, its hull was not

copper-sheathed. A further disadvantage, according to French observers, was a

poorly-trained crew and the poor quality of many of the guns. With the greater

part of the Spanish fleet, the ship’s home base was Cadiz.

In the course of its 38-year plus career, the Santísima

Trinidad was careened or refitted three times, and spent almost 20 of those

years out of service. This last was typical of ships in other navies: if there

was no war on, crews were discharged and the ship held ‘in ordinary’. Ships in

reserve had their guns removed, to reduce strain on the innumerable joints and

brackets of the hull and gun-decks.

Surrender at

Trafalgar

At Trafalgar, captained by Francisco Javier Uriarte and

carrying the pendant of Rear Admiral Baltasar de Cisneros, it was flagship of

the Spanish squadron, painted dark red with white stripes. In line just ahead

of Admiral Villeneuve’s Bucentaure, it was in the thick of the central battle,

heavily raked by broadsides from HMS Neptune.

After four hours, by 2:12pm, all three masts were gone; an

eyewitness wrote: ‘This tremendous fabric gave a deep roll, with a swell to

leeward, then back to windward, and on her return every mast went by the board,

leaving it an unmanageable hulk on the water.’ The ship was compelled to

surrender (as painted below in the Surrender of the Santísima Trinidad to

Neptune, The Battle of Trafalgar, 3 PM, 21st October 1805 by Lieutenant Robert

Strickland Thomas).

After the battle it was taken in tow by HMS Prince, but in

the storm which followed, the tow could not be held, and Santísima Trinidad was

scuttled on 22 October.

Specification (1768)

Dimensions Length

60.1m (200ft), Beam 19.2m (62ft 9in), Draught 8.02m (26ft 4in)

Displacement

c4309 tonnes (c4750 tons)

Rig 3 masts,

square-rigged

Armament (1768)

30 36-pounder, 32 24-pounder, 32 12-pounder, 18 8-pounder guns

Complement 950