The Peoples Liberation Army’s communications were inferior in comparison to the UN forces. Radios were only issued down to regiments, who then used field telephones if available, to contact their battalions. Battalions then used bugles, whistles and runners to talk to each other and their subordinate companies.

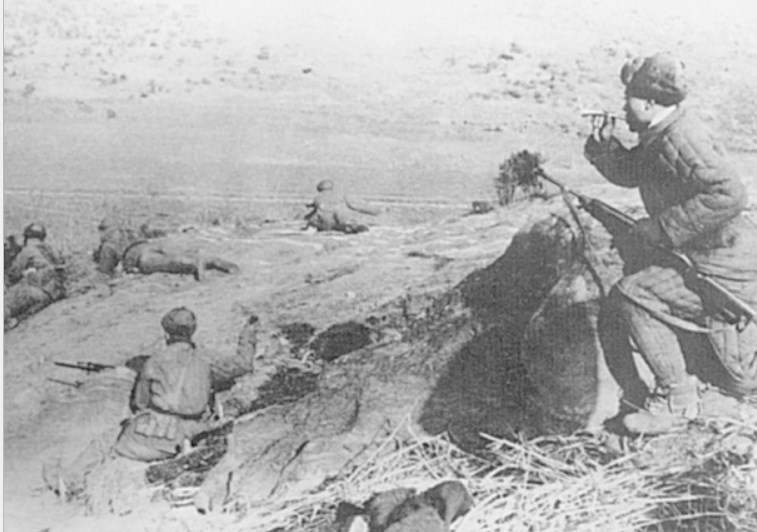

Chinese reinforcements advancing into North Korea. The Chinese enjoyed a virtually unlimited supply of manpower. Note the foliage being carried by the soldiers; the concealment skills of the Chinese were legendary.

25 October – 24

December 1950

It should have come as no surprise to General MacArthur that

the Chinese decided to cross the border in order to protect their interests.

They certainly did not want a unified South Korea, backed by the United States,

across the Yalu River. They made it clear through diplomatic channels that they

would intervene if non-South Korean troops crossed the 38th Parallel.

It was not going to be easy. On 2 October Chairman Mao sent

a cable to Stalin outlining the problems that they would be facing. An American

Corps comprised two infantry divisions and a mechanized division with 1,500 guns

of 70mm to 240mm calibre, including tank guns and anti-aircraft guns. In

comparison each Chinese Army, comprising three divisions, had only thirty-six

such guns. The UN dominated the air, whereas the Chinese had only just started

training pilots and would not be able to deploy more than 300 aircraft in

combat until February 1951. To ensure the elimination of one US Corps, the

Chinese would need to assemble four times as many troops as the enemy – four

field armies to deal with one enemy Corps and requiring 2,200 to 3,000 guns of

more than 70mm calibre to deal with 1,500 enemy guns of the same calibre.

On 5 October 1950, the day after American troops crossed the

38th Parallel, Chairman Mao Zedong issued orders for the North East Frontier

Force of the Chinese Peoples Liberation Army to move up to the Yalu River.

Premier Zhou Enlai was sent to Moscow to persuade Stalin to provide aid and it

was agreed that Russian Mig-15 fighters would be sent to airfields in China and

painted in Chinese Air Force markings, but flown by Soviet pilots. They would

not provide air-ground support to the Chinese forces, but would engage United

Nations aircraft south of the Yalu River.

Because of this short delay, Mao postponed the intervention

of Chinese troops from 13 October to 19 October. Four Armies and three

artillery divisions were mobilized. Many were experienced troops who had fought

the Japanese in the Second World War and defeated the Nationalist Army of

Chiang Kai Shek afterwards. In the meantime, on the 15th President Truman flew

to Wake Island to meet with General MacArthur. They discussed the possibility

of Chinese intervention and Truman’s desire to limit the scope of the war.

MacArthur reassured Truman that the Chinese would not intervene and if they did

they would be easily defeated.

On 19 October, United Nations forces entered the North

Korean capital P’yongyang and on the same day the first troops from the Chinese

‘Peoples Volunteer Army’ crossed the Yalu River under great secrecy. As the UN

forces fought their way across the North Korean countryside, General Peng

Dehuai deployed his 270,000 troops in the mountains and waited for the enemy to

fall into the trap.

As the South Korean troops moved into the valleys heading

for the Yalu River, the Chinese watched and on 25 October, made their move. The

Chinese First Phase Campaign began on the morning of 25 October when the 118th

Division of the 40th Army wiped out an infantry battalion of the ROK 6th

Division a mere dozen miles from the Yalu River. At the same time the 1st ROK

Division ran into the Chinese 39th Army, which was tasked with the capture of

Unsan. The 15th Regiment was leading the division and it ground to a halt under

enemy mortar fire. Soon reports came in from the 12th Regiment on the left and

the 11th Regiment in the rear – the Chinese were trying to surround the

division. Colonel Paik immediately withdrew his division to Unsan and

established a defensive perimeter around the town. A captured Chinese soldier

was brought into his headquarters. He was wearing a thick, quilted uniform that

was khaki on the outside and white on the inside and it could be worn inside

out, to facilitate camouflage in snowy terrain. He admitted that he was from

China’s Kwangtung Province and a member of the 39th Army, subordinate to the

13th Army Group. They had boarded trains in September and headed for Manchuria.

They had crossed the Yalu River into Korea in mid-October, moving only at night

and had gone to great efforts to conceal signs of their movement. He said that

tens of thousands of his comrades were in the mountains around the 1st ROK

Division.

The report was passed on to General Willoughby, MacArthur’s

chief of intelligence, but it was ignored. He considered that the South Koreans

had encountered Chinese volunteers fighting with the North Koreans or Korean

residents in China having returned to fight for their homeland. The 1st Cavalry

Division was ordered to bypass the 1st ROK Division and continue the advance.

After six days of fighting the Chinese, surviving only due

to US tank and artillery support the 1st ROK Division was ready to break apart.

The three ROK divisions on its right flank had already retreated and Colonel

Paik knew that time was running out. He recommended to General Milburn the

Corps Commander, that they withdraw to the Chongchon River. They had lost over

500 men, killed or missing in action. Milburn agreed and they began to pull out

as the US 8th Cavalry Regiment of the 1st Cavalry Division moved past them to

cover the withdrawal.

Late in the evening of 1 November, with rocket artillery

support, four Chinese battalions from their 116th Division launched their

attack on two battalions of the 8th Cavalry. The sound of bugles echoed from

the surrounding hills and thousands of Chinese infantry began pouring down the

slopes towards the surprised cavalrymen. Throughout the night the Chinese

continued their attack, overrunning one position after another. Soon they were

so close that the artillery fire was no longer effective and the two battalions

tried to withdraw. However, by now the Chinese had got behind them and

established roadblocks on the main routes out of the town. The infantrymen

split up into small groups and took to the hills to try to find their way to

safety.

Early in the morning of 2 November the human wave of Chinese

fell upon the 3rd Battalion of the 8th Cavalry. They helped to seal their own

fate by allowing a company of Chinese commandos dressed in South Korean

uniforms to cross a bridge near the battalion command post, thinking that they

were ROK troops. Once across the bridge, the Chinese commander blew his bugle

and, throwing satchel charges and grenades, his men overran the command post

and killed many men still in their sleeping bags.

The 5th Cavalry Regiment tried to break through the Chinese

encircling the 8th Cavalry, but they were unable to cut their way through the

determined enemy and after suffering 350 casualties they withdrew, leaving the

survivors of the 8th Cavalry to fight their way to safety. Over 800 of them did

not make it, either dying on the battlefield or surrendering to the victorious

Chinese. It was the most devastating loss to the US forces so far in the war.

2 November was the day that the UN Offensive Campaign came

to a halt. The US-named Chinese Communist Forces Intervention Campaign began

the next day, 3 November and it would last until 24 January the following year.

The destruction of the 8th Cavalry heralded a change in the balance of power

and it began to shift in favour of the communists. They would refer to those fateful

eleven days, 25 October to 5 November as their Chinese First Offensive.

Other elements of the Eighth Army were also attacked and by

6 November the UN forces had pulled back to the line of the Chongchon River,

which runs from the west coast in a north-easterly direction towards the Chosin

Reservoir. Then as suddenly as they had appeared, the Chinese vanished into the

hills and valleys of the land stretching towards the border with China.

The Chinese had intended to push the UN forces back across

the Chongchon River and into P’yongyang, but they were running short of food

and ammunition and were forced to disengage on 5 November, thus ending the

Chinese First Phase Campaign. Apart from their victory at Unsan, they had also

destroyed the ROK 6th Infantry Division and one regiment from the 8th Division

at the battle of Onjong. In return, they had suffered nearly 11,000 casualties.

The Chinese victory at Unsan was a surprise to the Chinese

leadership and they intensely studied the performance of the 1st Cavalry

Division. It was noted that the American mechanized forces moved fast and

established defence works quickly. It was unfavourable to assault such defences

with massed infantry attacks.

General MacArthur could have halted the march to the Yalu

River after the heavy losses suffered by the Eighth Army at Unsan. It was clear

that the Chinese intended to defend the power stations supplying electricity to

Manchuria and that to continue advancing was to run the risk of full scale war

with China. He was undeterred and launched a ‘Home by Christmas’ offensive.

Historians still debate whether he had convinced himself that only a weak

Chinese force was present in Korea, or whether he wanted to deliberately

provoke war with China.

General Peng suggested to Mao that the UN forces might be

lured into preset ambushes as far north as possible, stretching their supply

lines and isolating them from each other. Mao approved the plan and Peng

instructed each CPVF Army to withdraw its main force further north, but leave

one division to lure the UN forces into the trap. They even released some 100

prisoners of war, including twenty-seven Americans, who were deliberately told

that they were being released because the Volunteers had to return to China due

to supply difficulties.

At this time the US-led United Nations Command comprised the

Eighth Army headquarters and the ROK Army headquarters, three US and three ROK

Corps headquarters, eighteen infantry divisions – ten ROK and seven US Army and

one US Marine, three Allied brigades and a separate airborne regiment. Total

ground forces came to 425,000 men, including 178,000 Americans, plus major air

and navy elements including aircraft carriers and fighters and bombers based in

South Korea and Japan.

Opposing them were the North Korean Army of eight Corps and

thirty divisions plus several brigades, although only two Corps of five

weakened divisions and two brigades were actually engaged in combat with UN

forces. The remainder of their forces had either withdrawn across the Yalu

River into Manchuria or were avoiding combat in the mountains along the border.

The main combat unit opposing the UN advance was the 300,000 strong Chinese

Peoples Volunteer Army. The hilly terrain on the northern bank of the Chongchon

River formed a defensive barrier that allowed the Chinese to hide their

presence, while the UN forces advanced. To make things worse, the battle was

also fought over one of the coldest winters in 100 years, with temperatures

falling as low as –30°F (–34°C).

With the disappearance of the Chinese forces, the UN advance

resumed on 24 November with General Walker’s Eighth Army moving up the west

coast and General Almond’s X Corps due to start moving up the east coast three

days later. The two forces were separated by the virtually impassable Taebaek

Mountains. The Eighth Army comprised the reconstituted ROK II Corps on the

right flank and leading the advance the US I Corps to the west with the US IX

Corps in the centre. They moved cautiously in line to prevent a repeat of the

earlier ambushes in the first Chinese campaign. Despite their lack of manpower,

the US Eighth Army had three and a half times the firepower of the opposing

Chinese forces. In addition the US Fifth Air Force providing the air support,

had little opposition due to the lack of Chinese anti-aircraft weapons.

Morale among the American troops was high, boosted by a

Thanksgiving feast with roast turkey on the eve of the advance. However, this

led to overconfidence and some of the men had discarded equipment and

ammunition before the advance. One rifle company from the US IX Corps began its

advance without carrying helmets or bayonets and there were less on average

than one grenade and fifty rounds of ammunition carried per man. In addition,

because the US planners did not foresee that the campaign would continue into

the winter, the men of Eighth Army started the advance with a shortage of

winter clothing.

What they did not know was that the 13th Peoples Volunteer

Army Group was hiding in the mountains, with the 50th and 66th Army to the

west, the 39th and 40th Army in the centre and the 38th and 42nd Army in the

east. General Peng’s plan was for the 38th and 42nd Army to first attack the

ROK II Corps and destroy the UN right flank, then cut behind the UN lines. At

the same time the 39th and 40th Army would hold the US IX Corps in place, so it

could not reinforce the ROK II Corps. The 50th and 66th Army would check the

advance of the US I Corps.

A Chinese Army was similar to a Corps in the American Army,

consisting of three divisions of around 10,000 men each, although actual

strength was usually 7,000–8,500. Each division had three 3,000-man regiments

of infantry, whereas an American division consisted of three regiments of

infantry, three battalions of 105mm artillery, one battalion of 155mm

artillery, an anti-aircraft battalion, a tank battalion and other supporting

units, totalling 20,000 men.

The Chinese forces were basically infantrymen, with almost

no heavy weapons other than mortars. There was also only one rifle available for

every three Chinese, mostly captured from Japanese during the Second World War

or the Chinese Nationalist forces during the civil war. Most were US made small

arms such as the Thompson sub-machine gun, M1 Garand Rifle, M1918 Browning

Automatic Rifle, the bazooka and the M2 mortar. They were encouraged to use

captured enemy weapons whenever possible and to take weapons from their dead

comrades. Because most of their artillery had been left behind in Manchuria,

mortars were the only heavy support available for the Chinese. For the coming

offensive the average soldier was issued with five days’ worth of rations and

ammunition. To compensate for these shortcomings, the Chinese relied

extensively on night attacks and infiltration to avoid the UN firepower. As

they had little mechanized transport they could avoid the roads and manoeuvre

over the hills, bypassing the UN defences and surrounding isolated UN

positions.

Four of the Chinese armies, the 38th, 40th, 50th and 66th,

struck the Eighth Army, on the night of 25 November. The 40th Army hit the

three regiments of the US 2nd Infantry Division at Kunu-ri on the Chongchon

River, as well as the US 25th Infantry Division on their left flank. Although

they suffered heavy casualties, the Chinese pressed on with their attack, tying

down the American units while a new offensive fell on the ROK II Corps on the

right hand side of the Eighth Army line. The 38th Army broke through the ROK

line in the gap between the 7th and 8th Divisions and established roadblocks to

their rear and by the end of 26 November the II ROK Corps front broke and the

South Koreans began to retreat, thus exposing the right flank of the Eighth

Army.

Heavy attacks on the US 25th Infantry Division and the ROK

1st Division soon followed and both units began to retreat under the pressure.

The village of Kunu-ri became a major bottleneck for the US IX Corps’ retreat

and in an effort to stabilize the front on 28 November, General Walker ordered

the US 2nd Infantry Division to withdraw and set up a new defensive line at

Kunu-ri. General Peng had also recognized the importance of the village and

ordered his 38th Army to cut the IX Corps line of retreat. Its 114th Division

was to capture Kunu-ri while the 112th Division would follow on a parallel

route through the hills north of the road.

By mid-afternoon on 28 November all US and ROK forces were

in retreat. The retreat was made even more difficult by the thousands of

refugees heading south away from the fighting. Amongst them were North Korean

and Chinese infiltrators, dressed in civilian clothes, who would pass the

American check points and then turn and open fire on them. Eventually the ROK

Police would try to route the columns of refugees away from the roads, while on

other occasions both US and ROK troops would open fire on refugees coming near

to their positions.

The US 2nd Infantry Division was positioned in the centre of

Eighth Army’s front, with the Turkish Brigade ten miles away on its right

flank. The Turkish Brigade was ordered to block the Chinese advance and

suffered heavy casualties before it broke out and joined up with the 2nd

Division on 29 November. This delaying action allowed the 2nd Division to

secure Kunu-ri on the night of 28 November.

On the night of 28 November General MacArthur gathered his

field commanders for a conference in Tokyo. He instructed Walker to withdraw

from the battle before the Chinese could surround the Eighth Army and retreat

to a new line at Sunchon, thirty miles south of Kunu-ri.

The full weight of the Chinese offensive now fell on

Lieutenant General Laurence B. Keiser’s 2nd Infantry Division as it prepared to

withdraw from Kunu-ri. The Chinese 113th Division had advanced forty-five miles

in fourteen hours and now occupied strategic points in the rear of the Division

where they established road blocks on the division’s withdrawal route south to

Sunchon.

General Keiser believed that the Chinese only had one

roadblock four miles from his position, but in fact they had constructed a

series of reinforced roadblocks throughout the length of the entire valley. As

the division began to withdraw on the morning of 30 November, it found itself

having to ‘run the gauntlet’ of the road blocks and the thousands of Chinese

occupying the high ground along the route. By the time the General realized his

mistake, it was too late to turn the division around and take the road to the

east and then south to Sinanju. The main Chinese advance was being held back by

the 23rd Infantry Regiment, commanded by Colonel Freeman and he did not feel

that they could hold out long enough for the entire division to turn around and

return to the Sinanju road. The division would just have to run the gauntlet.

At 1300 hours a column of US tanks led the way through the

valley. They came under intense fire and had to stop twice to push aside

barricades of destroyed Turkish trucks set up by the Chinese. By 1400 hours

they were clear of the ambush and had linked up with British troops from the

29th Commonwealth Brigade sent to clear the road to the south. Unfortunately,

while the tankers had to stop to clear the barricades, the trucks following

them also had to halt. Then the soft-skinned vehicles became easy targets for

the Chinese machine guns and mortars. Their occupants would have to exit the

vehicles and take cover in the ditches at the side of the road and watch their

trucks being destroyed. When there was a lull in the firing, drivers would

scramble out of the ditches and back into their trucks and drive on, without

waiting for their passengers to climb back on board.

Lieutenant Colonel William Kelleher of the 1st Battalion,

38th Infantry Regiment later recalled: ‘For the next 500 yards the road was

temporarily impassable because of the numerous burning vehicles and the pile up

of the dead men, coupled with the rush of the wounded from the ditches,

struggling to get aboard anything that rolled … either there would be bodies in

our way, or we would be almost borne down by wounded men who literally threw

themselves upon us … I squeezed a wounded ROK soldier into our trailer, but as

I put him aboard, other wounded men piled on the trailer in such numbers that

the jeep couldn’t pull ahead. It was necessary to beat them off.’

The most dangerous part of the road leading south to Sunchon

was an area known simply as ‘The Pass’ where the hillside was steepest and the

road was at its most narrow point. Most of the casualties occurred in this

bottleneck. Soon the road was littered with dead and dying troops and by the

time General Yazici’s Turkish brigade came to take its turn, all road movement

had stopped because of the number of destroyed and abandoned trucks on the

road. Two companies of Turks fixed bayonets and charged up the eastern slope of

the mountains, while US air support strafed the Chinese positions. General

Keiser sent two of his remaining tanks to clear the wreckage on the route and

the following columns began to creep forward again.

In the meantime, Colonel Freeman realized what was happening

in the valley to his rear and very wisely decided to take his men down the road

to the east. In one of the last acts of the battle, the 23rd Infantry Regiment

fired off its stock of 3,206 artillery shells within twenty minutes and the

massive barrage shocked the Chinese troops from following the regiment. They

broke contact with the Chinese and the 23rd Infantry Regiment lived to fight

another day. The other units of 2nd Division would not be so lucky. As night

fell, General Keiser lost his air support and the Chinese infantry crawled down

the hillsides to swarm over the road. The brunt of their attack fell on the

38th and 503rd Field Artillery Battalions and the 2nd Engineer Combat

Battalion, who had to abandon their equipment and fight their way out on foot.

The majority of them would be killed or captured.

The commander of the 2nd Engineer Battalion, Colonel Alarich

Zacherle, had asked General Keiser days before the start of the Chinese

offensive, to redeploy his unit south to P’yongyang, as their bridging

equipment and bulldozers would not be needed in the mountains. He refused and

only 266 of the 900 men of the battalion survived. The Colonel would spend the

rest of the war in a Chinese prison camp.

With the road now blocked with the destroyed equipment of

the two artillery battalions, the rest of the division was forced to take to

the hills and find a way past the hordes of Chinese. The US 2nd Infantry

Division had ceased to exist as an effective fighting force; it was the greatest

US defeat of the whole war.

Most of the division’s transport was lost during the

retreat; the 37th Field Artillery Battalion for example, lost thirty-five men,

ten howitzers, fifty-three vehicles and thirty-nine trailers. Unit integrity

broke down and there were recriminations afterwards when it became clear that

the divisional commander and other ranking officers had escaped, leaving 4,500

men, almost a third of the division’s strength dead or in captivity. At that

time, a US infantry regiment was authorized 3,800 men and from the three

regiments in the division, the 9th Infantry lost 1,474 men, the 38th Infantry

lost 1,178 men and the 23rd Infantry 545 men. The division also lost sixty-four

artillery pieces, hundreds of trucks and nearly all of its engineer equipment.

The Chinese and North Koreans would make good use of their war booty over the

coming months, while columns of weary 2nd Division prisoners of war trudged

their way north to communist prison camps. It was estimated that 3,000 US POWs

were taken, the largest such group captured by the Chinese during the war.

The other US unit to report significant losses was the US

25th Infantry Division with 1,313 casualties. The Turkish Brigade was rendered

ineffective after losing 936 casualties, along with 90 per cent of its

equipment and vehicles and 50 per cent of its artillery. Chinese casualties

were estimated at 45,000 with half due to combat and the rest to the lack of

adequate winter clothing and the lack of food. For its role in establishing the

Gauntlet against the US 2nd Infantry Division the Chinese 38th Army was awarded

the title ‘Ten Thousand Years Army’ by General Peng on 1 December 1950.

The Eighth Army was now reduced to two Corps, composed of

four divisions and two brigades, so General Walker ordered his Army to abandon

North Korea on 3 December, much to the surprise of the Chinese commanders. The

following 120 mile withdrawal to the 38th Parallel is often referred to as the

longest retreat in US military history. Walker was unaware that the Chinese

13th Army Group was half-starved and incapable of further offensive operations.

The great ‘Bug Out’ had begun.

Across the other side of the peninsula, General Almond’s X

Corps had begun moving northwards on 27 November, with the two divisions of the

ROK I Corps following the coastal roads, the US 7th Infantry Division in the

centre and the 1st Marine Division on the left, all aiming for different points

on the Yalu River. The Marines were to pass along both sides of the Chosin

Reservoir, tie in with the right flank of Eighth Army and then press on a

further sixty miles to the Yalu. The commander of the 1st Marine Division,

Major General Oliver P. Smith, was wary of advancing too fast, despite the

insistence of the Corps commander. The terrain in that part of Korea consisted

of narrow roads, often cut by gullies and valleys with imposing ridgelines and

mountains surrounding them. Smith wanted his men to advance cautiously, in

contact with each other and maintaining unit integrity. He made the correct

decision.

General Almond then ordered the 31st Regimental Combat Team

of the 7th Division to relieve the 5th Marine Regiment on the east side of the

Chosin Reservoir, so the Marines could concentrate their forces in the west.

However, the 31st RCT as well as the rest of the 7th Division were widely

scattered and the units arrived at the east of the reservoir in bits and

pieces. They eventually formed themselves into Task Force Faith and Task Force

McLean, named after their commanders.

Late on 27 November, the Chinese Offensive began on the

eastern front with the 150,000 strong Ninth Army Group, comprising the 20th,

26th and 27th Armies advancing towards the 1st Marine Division and the US 7th

Infantry Division. The CPVF 79th and 89th Divisions fell on the 5th and 7th

Marine Regiments on the west side of the reservoir and the 80th Division

surrounded Task Force McLean on the east side. During heavy fighting Colonel

McLean was captured and Colonel Faith took over command. The 2,500 men of Task

Force Faith tried to break through to the Marines in the south, taking their

600 wounded men with them. The Chinese were too strong for them though and only

half would eventually make it through. The wounded Colonel Faith and all of the

wounded were left behind to their fate.

To the west of the reservoir, the 5th and 7th Marines began

a fighting withdrawal back to Hagaru-ri at the south end of the reservoir and

then a further fifty miles south-east to Hungnam, a port on the east coast from

where they would be withdrawn by sea. The epic retreat would see the 1st Marine

Division bring their dead and wounded with them as they fought their way slowly

to safety. During the day they could rely on close air support from their own

aircraft, but during the night they had to contend with the bitter cold and the

Chinese creeping closer and closer to their columns. Finally, 11,000 Marines

and 1,000 Infantry soldiers made it to Hungnam where they were taken off by the

Navy. They were followed by the ROK I Corps, the battered US 7th Infantry

Division and the newly arrived US 3rd Infantry Division: over 105,000 troops,

18,000 vehicles and 350,000 tons of bulk cargo, as well as 98,000 refugees. On

24 December the port was evacuated and all remaining stores in the warehouses

ashore destroyed in a massive series of explosions. The ships were heading for

Pusan in the South, where the troops would be refitted and redeployed to the

front to help Eighth Army hold the line.

Although the Chinese Ninth Army Group scored the CPVF’s only

major victory in three years of war when it wiped out the entire 32nd Regiment

of the 7th Division, it suffered terribly in the Korean winter. More than

30,000 officers and men, some 22 per cent of the entire Army Group, were

disabled by severe frostbite and over a thousand died.

In the meantime Eighth Army had pulled back from the

Chongchon River and was concentrating near P’yongyang. General Walker realized

that his forces were in no condition to hold a defensive line so far north and

approved a further withdrawal of almost a hundred miles to the Imjin River,

north of Seoul. By the end of December the UN line was established with the US

I and IX Corps and the ROK III, II and I Corps running from the west coast to

east. The Chinese did not pursue them; they needed to resupply and refit, as

did the UN forces now licking their wounds and digging new defensive positions

along the Imjin River. The Second Campaign represented the peak of CPVF

performance in the Korean War. From now on things would get harder. They were

hampered by their weak firepower compared to the UN forces and they would have

to follow them southwards to continue the battle, where the enemy’s superior

weapons and air power could be brought to bear on them. There were logistical

constraints as well; an overstretched supply line, bad roads, a shortage of

trucks and marauding UN aircraft combined to cause food shortages where some

CPVF units only had food for one week.

General Walker’s part in the war came to an end on the

morning of 23 December, while he was out on an inspection tour in his jeep. Ten

miles north of Seoul, a Korean truck driver pulled onto the wrong side of the

road and collided head on with his jeep, killing the General. He would be

replaced by Lieutenant General Matthew B. Ridgway, a famed airborne commander

from the Second World War, whose first task would be to turn morale around and

improve the fighting ability of the Eighth Army.