The military hegemony of France in Europe and in many

regions overseas began on 19 May 1643 with the destruction of the Spanish

Netherlands Army at Rocroi by a French army led by the 21-year-old Duke of

Enghien (later Prince of Conde, the “Great Conde”). The young duke’s

remarkable victory over Spain’s hardened veterans signaled the end of Spain’s

military predominance (which dated from the sixteenth century) and represented

the fruition of the military reorganization initiated by King Louis XIII’s

premier, Armand Jean du Plessis, cardinal-duke of Richelieu.

On the foundation laid by Richelieu, talented military

leaders like Conde, Turenne, Luxembourg, Vauban, Catinat, Villars, Vendome,

Boufflers, and Saxe, and a succession of accomplished royal ministers, like

Colbert and Louvois, built the edifice of France’s military greatness.

France was ruled during its ascendancy by the “Sun

King,” Louis XIV (reigned 1643-1715), whose ambition and territorial

designs caused many of the great wars that wracked Europe during the last

decades of the seventeenth century. French hegemony was first checked by

coalitions led by England and Holland and finally ended by Great Britain in the

Seven Years’ War (1756-63), a true world war in which France lost most of its

great colonial empire.

Henry IV (“le Grand”)

The end of the long period of religious-civil wars in France

(Edict of Nantes, 1598) was also the end of the latest French struggle with

Hapsburg Spain (Treaty of Vervins), with which France had been at war more or

less continually since the beginning of the sixteenth century. The new French

king, Henry IV, had triumphed over his enemies, foreign and domestic, but was

shrewd enough to recognize that he had gained as much by compromise and cynical

accommodation as by military prowess. The conflict with the Spanish Hapsburgs

(and their Austrian cousins) was more suspended than resolved. The debilitating

domestic religious question was solved temporarily by permitting the Huguenots

to erect a kind of independent republic based on their centers of influence,

chiefly in the south and southwest of France. But, fundamentally, the religious

question had been deferred, not settled. Much depended on the king’s political

skills and vision, not only for France, but for Europe.

At this time, the kingdom’s energies were directed toward

re-establishing order and rebuilding the economy, as the Memoires of the Duke

of Sully recount. In foreign affairs, the king conceived a fantastic project

for a “United States of Europe,” a precursor of the present-day European

Union. But how serious he was, and what the results of his various schemes

might have been, remain subjects for conjecture: Henry IV was assassinated by a

fanatic in 1610. He was succeeded by his son, Louis XIII (reigned 1610-43), who

was 9 years old.

Louis XIII (“le

Juste”)

Internal Conflicts

Louis’s reign was troubled by internal division, conspiracy,

and conflict. In part this was due to the king’s youth and the constant

jockeying for power and influence at court among regents, favorites, advisers,

and councilors; in part it was due to the renewed outbreak of religious and

civil wars, as the problems left unresolved at the accession of Henry IV

resurfaced.

It is remarkable that, at this time, France was virtually

bereft of armed forces. The “peace dividend” attendant to the

accession of Henry IV was manifest in the purposeful neglect of the army and

navy. In particular, Henry had allowed the ancient companies of gendarmes

(regular heavy cavalry) to dwindle to nothing, since they had been arrayed against

him in the civil wars. Even the royal household troops, the fabled Maison du

Roi, had been cut back severely, and some units existed only as sinecures for

Henry’s old comrades in arms.

Louis XIII, his favorites, and his ministers gradually

rebuilt the Maison, adding new units and reinforcing the old ones, so that the

Royal Army always had a well-drilled, professional core. In the dizzying

succession of internal wars that beset the country until the final defeat of

the Huguenots (1628), the professionalism of the Royal Army made the

difference.

Louis’s enemies did not want for armed men, nor for

enthusiastic amateurs to lead them, but the armies of the nobles (les grands)

and the Huguenots could not stand up to the Royal Army in the field. The wars

were characterized by sieges-in particular, the epic siege of the Huguenot

stronghold of La Rochelle (1627-28). At the end of the wars, the king’s chief

minister, Cardinal Richelieu, stood in triumph over his enemies. Henceforward

until his death (1642), he was effectively France’s ruler.

Richelieu

The conclusion of the internal wars allowed Richelieu to

turn his attention to foreign affairs, his true metier. In Richelieu’s eyes,

France’s principal enemy was the House of Hapsburg, and particularly the

Spanish Hapsburgs, whose domains or dependents confronted France on all its

land frontiers. Thus, from 1629 until 1659, France was almost continually at

war with Spain, either at first-hand or by proxy.

These wars included the War of the Mantuan Succession

(1629-32) and the Franco-Spanish War (1635-59), which just preceded open French

involvement in the Thirty Years’ War (French phase, 1636-48) and continued long

afterward. In this series of conflicts, France was ultimately successful,

despite political divisions manifested by the various civil wars of the

antiministerial Fronde (1648-53) and the treason of Conde, who threw in with

the Spanish after his defeat as the leader of the Frondeurs (he served as a

Spanish generalissimo until 1659).

France’s success in this period may be attributed almost

entirely to the policies of Richelieu. He reformed and reorganized the army,

eliminating some of the worst abuses of the oligarchic spoils system by

subordinating the entirely aristocratic officer corps to central authority. He

achieved some success in enlarging and professionalizing the native French

forces and ending the Crown’s dependence on the superb but not always reliable

mercenary contingents that historically had constituted the fighting core of

the French army.

Richelieu also virtually founded the French navy, which had

hardly existed as a permanent force before his ministry. For a brief (and

remarkable) period the navy won several victories against the Spanish. The

greatest French admiral of the period was the cardinal’s brilliant nephew,

Maille-Breze (1619-49).

But Richelieu’s achievements did not long outlast him. His

successor, Cardinal Mazarin (Giuilo Mazarini, premier 1642-61), allowed the

navy to sink into decline, and it was of little military value until its true

foundation as a professional service around 1669 by the great navy minister,

Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619-83). The army, however, retained a measure of

efficiency, and its greatest moments were ahead of it.

Louis XIV (“le

Roi Soleil”)

The Sun King’s reign had begun in 1643, but in fact Mazarin

ruled France until he died in 1661, when Louis proclaimed that henceforth he

would be his own chief minister. The next 54 years were a period of splendor

and magnificence for France, not only in the arts but also in military affairs.

France was at the zenith of its power.

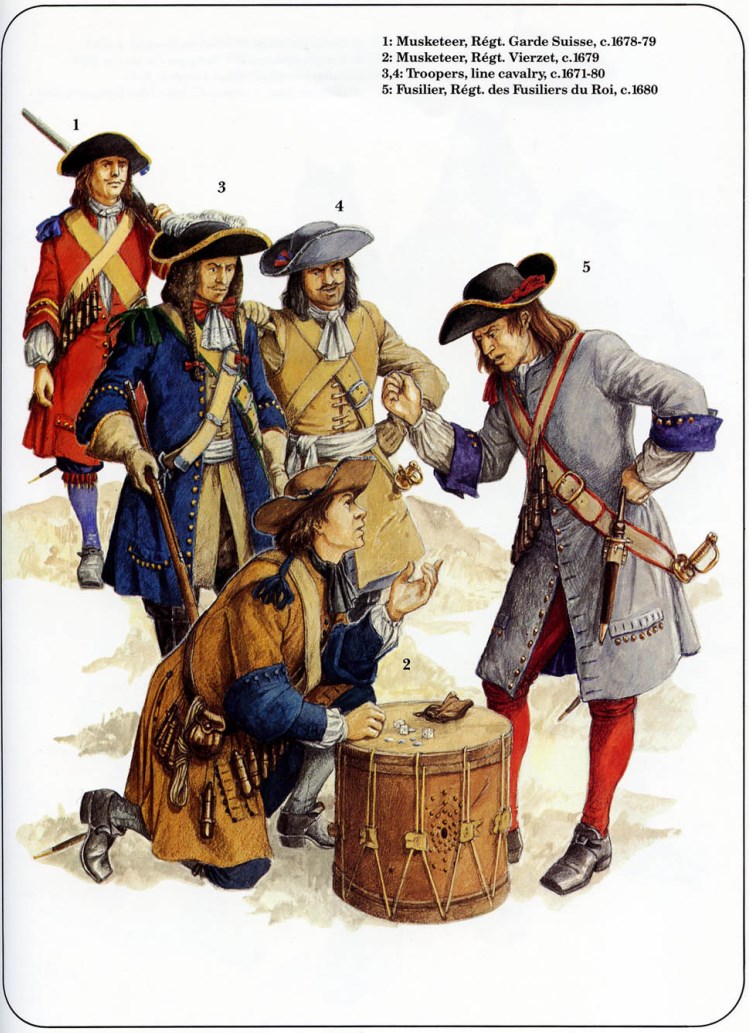

In the military sphere, France was organized for war so

thoroughly that no one power could long hope to withstand it. And Louis’s

ambition for territorial aggrandizement might have startled even his more

aggressive ancestors.

Louvois

While Colbert reorganized the financial structure of the

nation and launched an ambitious naval building program, his bitter enemy, the

equally remarkable war minister Francois Michel Le Tellier, marquis de Louvois

(1641-91), reorganized the army. Louvois was assisted in this work by Turenne,

who was made marshal-general in 1660 to give him authority over all his

redoubtable contemporaries in the marshalate. Turenne in turn was assisted by

three brilliant but largely forgotten subordinates-Martinet, Fourilles, and Du

Metz-each responsible for the reorganization of a single combat arm: infantry,

cavalry, and artillery, respectively. The result of this immense effort was the

first truly modern army: a permanent professional force, well organized,

trained to a relatively high degree of efficiency, and subordinated to a

powerful minister supported by a large, proficient civilian bureaucracy.

Logistical support of field armies was facilitated by the

magazine system created by the great engineer Vauban. The rationalization of

logistics, combined with the centralized control and direction of the marshaled

human and material resources of the nation-state, made larger armies possible.

Whereas, during the Thirty Years’ War, the average field army had numbered

about 19,000 men, the late-seventeenth-century wars of Louis XIV were fought by

field armies two to three times larger. To compound France’s advantages in this

period, the magnificent armies created by Louvois were led by perhaps the

greatest galaxy of military talent ever assembled.

The Wars of Louis XIV

Louis’s wars of aggression, conducted between 1667 and 1714,

involved his blatant and barely rationalized attempts to expand France’s

frontiers, particularly in the northeast (Flanders) and east (along the Rhine),

at the expense of the moribund Spanish Empire and the hopelessly divided,

invitingly weak Holy Roman Empire. These expansionist wars began in earnest

with the War of Devolution (1667-68) and the Dutch War (1672-79), in which

France gained Franche-Comte and many strong places along the frontiers. France’s

principal enemy was Holland, the architect of strong coalitions which alone

could hope to oppose France. Indeed, in this period, France was virtually

isolated diplomatically. The French armies, led by Turenne and Conde, won

brilliant victories in the field, notably at Seneffe (11 August 1674), where

Conde defeated a Dutch-Spanish army led by William of Orange, the Dutch

stadtholder, and at Sinzheim (16 June 1674), Enzheim (4 October 1674), and

Turckheim (5 January 1675), in which Turenne gained a trio of remarkable

victories against the coalition armies along the Rhine.

The period following the Treaty of Nijmegen (6 February

1679) was marked by French bullying along the Rhine and further French

expansion as Louis’s “Chambers of Reunion” decreed several territories

and towns “French” (since at one time or another they had belonged to

any of several recent French territorial acquisitions). French troops promptly

moved in to enforce the decisions of these courts, and the German emperor was forced

to accede to this latest aggression. Louis followed up by revoking the Edict of

Nantes, which had guaranteed freedom of worship to the Huguenots (1685). Europe

was appalled, and France was much weakened by the emigration of thousands of

her most industrious people.

Further French threats and aggressions along the Rhine led

to the formation of the Dutch-inspired anti-French League of Augsburg, which

consisted of virtually all the powers of Europe except for England (9 July

1686). But the English Revolution of 1688 led to the exile of the English king

James II. When William of Orange and his wife, Mary, James’s daughter, took the

English throne, England joined the League, which became the Grand Alliance (12

May 1689).

Meanwhile, the War of the League of Augsburg (1688-97) had

broken out, and France confronted the coalition on land and sea. A new

generation of French military leaders soon proved their mettle. In Flanders,

the Marshal Duke of Luxembourg, Conde’s protege, won great victories over the

coalition at Fleurus (1 July 1690), Steenkerke (3 August 1692), and Neerwinden

(1 August 1693). In Italy, Marshal Catinat knocked Savoy out of the war after

winning the decisive Battle of Marsaglia (4 October 1693). At sea. however, the

French were beaten badly at Cap La Hogue (May 1692).

This war was also a true “world war.”‘ since it

involved the American and Indian-subcontinent colonies of the belligerents. In

America, it was known as King William s War and involved fighting between the

French and English and each side s Indian allies. The Treaty of Ryswick (1697)

that ended the war was unremarkable. In the complex territorial provisions.

France gained Alsace and Strasbourg.

The imminent extinction of the Spanish Hapsburg dynasty

preoccupied Europe in the years following the Treaty of Ryswick. When Charles

II. Spain’s feeble-minded, childless king, finally died in 1700. Louis advanced

the claim of his grandson. Philip of Anjou, to the Spanish throne. Since the

European powers could not countenance a union of Spain and France, this brought

on the War of the Spanish Succession 1701-1714. in which France once again

squared off against an all-European coalition.

In this war, France for once was decidedly deficient in

military talent. Against the genius of the great allied commanders Marlborough

and Eugene of Savoy. France had mostly second-rate marshals and generals (Luxembourg

had died in 1695). The allies won a succession of striking victories: Blenheim (1704),

Ramillies (1706), Turin (1706), and Oudenarde (1708). The French gained some

successes in Italy and prevailed in Spain. The allies won the bloody Battle of

Malplaquet (11 September 1709) at tremendous cost, and England retreated from

the war effort in revulsion at the casualties. The French cause was helped

immeasurably by the brilliant Marshal Villars. whose victories improved France’s

negotiating position as the war wound down.

In 1713 and 1714. the exhausted belligerents negotiated

treaties ending the war. Philip of Anjou was recognized as king of Spain, but

the crowns of France and Spain were permanently separated. Louis XIV died in

1715 and was succeeded by his great-grandson. Louis XV.

Louis XV (“le

Bien-Aime”)

The reign of Louis XV 1715-74 was marked by the gradual

decline of the military machine created by Louvois and Turenne. The officer

corps grew alarmingly, until by mid-century the proportion of officers to

enlisted men was 1 to 15. Moreover, the quality of the officer corps

deteriorated: many were weak, incompetent, venal, or amateurish. Inevitably,

discipline suffered, and the once-proud army became the object of contempt-an

‘”unqualified mediocrity” in the eyes of many.

The reign was marked by the complete reversal of Louis XIV’s

foreign policy, but France’s military commitments did not diminish appreciably,

as Europe’s coalition wars continued undiminished. France was allied with

recent enemies Britain. Holland, and Austria against its former ally Spain in

the War of the Quadruple Alliance (1718-20). In the War of the Polish

Succession (1733-38). France supported the claim of Stanislas Leszczynski

(Louis XV’s father-in-law) to the Polish crown against Saxony, Austria, and

Russia. France’s most distinguished soldier during this period was James

Fitzjames, duke of Berwick and marshal of France. Berwick, an illegitimate son

of England’s King James II, was killed in action at the Siege of Philippsburg

(12 June 1734). The Philippsburg campaign was also the last for a long-time

antagonist of France, Prince Eugene of Savoy.

The War of the

Austrian Succession (1740-48)

Although a guarantor of the Pragmatic Sanction, in this war

France was allied with Prussia, Bavaria, Saxony, Savoy, and Sweden against

Austria, Russia, and Britain. France did not officially enter the war until

1744, but French “volunteers” served from 1741-a decidedly modern

piece of disingenuousness.

The war marked the emergence of one of France’s greatest

soldiers, Maurice, comte de Saxe (1696-1750), a German by birth-one of 300-odd

illegitimate children of Augustus II “the Strong, ” elector of Saxony-a

military genius and himself a prodigious womanizer. Campaigning in Flanders,

the Austrian Netherlands, and Holland, Saxe won victories against the allies at

Fontenoy (10 May 1745), Rocourt (11 October 1746), and Lauffeld (2 July 1747).

Saxe’s success in the Low Countries was not matched by his

contemporaries in other major theaters-Italy and Germany. At sea, the British

had the upper hand against the French and Spanish fleets. In North America

(King George’s War), France fared miserably, incurring serious defeats by the

British and British colonials and native American allies. In India, however,

Dupleix was successful at Madras and in the Carnatic.

The Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748), ending the war,

restored all colonial conquests to their prewar status. France gained nothing

by the European provisions; essentially, the war had been a failure.

The Seven Years’ War

(1756-63): The Nadir

In the Seven Years’ War in Europe, France and its principal

allies, Austria (the Empire) and Russia, contended against the numerically

inferior forces of Prussia and Great Britain. The allied powers, operating on

exterior lines, made several poorly coordinated attempts to crush King

Frederick the Great of Prussia by convergent invasions of Hanover and Prussia.

Initially, the French, under Marshal Louis d’Estrees, were successful against

the British-Hanoverian army led by the son of King George II, William Augustus,

duke of Cumberland-whom Saxe had beaten at Fontenoy (despite the splendid

bravery of the British- Hanoverian infantry).

Defeated at Hastenbeck (26 July 1757), Cumberland was

trapped at KlosterZeven (Zeven) and forced to concede Hanover to the French.

The Convention of Kloster-Zeven was the worst British surrender until Dunkirk

(1940), not excepting Yorktown. D’Estrees’ replacement, the Marshal-Duke Louis

de Richelieu, failed to cooperate with Charles de Rohan, prince de Soubise, and

the prince of Saxe-Hildburghausen at the head of the Franco-Reichs army.

Despite great numerical superiority, the allies were defeated badly by

Frederick at Rossbach (5 November 1757).

The great victory at Rossbach eliminated one of two French

armies committed to German) and effectively allowed Frederick to concentrate

his energies on the Austrians and Russians. Henceforth, the French were opposed

on the Rhine front by the gifted Prince Ferdinand of Brunswick. Louis, marquis

de Contades. was defeated by Ferdinand at Minden (1 August 1759) and the French

were driven back to the Rhine. Subsequently, Ferdinand contended successfully

against the French (1760-62), finally driving them across the Rhine.

In the New World, the French, led by the brilliant Louis

Joseph, marquis de Montcalm-Gozon. were initially successful (French and Indian

War), but Montcalm was defeated by James Wolfe at Quebec (13 September 1759),

and the British conquest of Canada was completed within a year. Both Montcalm

and Wolfe died in the battle that decided the fate of a continent.

In India, weak French forces were led by Count Thomas Arthur

Lally, a distinguished veteran of Irish descent, who was beaten as much by the

ineptitude and machinations of his officers as by the genius of the British

soldier Sir Eyre Coote. Lally lost India and went to the scaffold for it, a

miscarriage of justice memorialized by Voltaire in Fragments of India.

The French navy was no match for the British at sea. British

naval superiority contributed to the relative isolation of French colonial

forces and the disparity in strategic mobility, numbers, and resources wherever

the two powers confronted one another.

The Treaty of Paris (1763) marked the political and military

humiliation of France and the ascendancy of Britain in Europe and overseas.

France lost most of its North American and Caribbean empire, including Canada,

and French India was practically dismantled. In Europe, France had sunk so low

that it was almost eclipsed by a resurgent Spain, led by King Charles III

(reigned 1759-88).

Military Reform and

Rebirth

France had always been a congenial environment for military

thinkers-and not a few eccentrics. Among the great theorists of the eighteenth

century were Jean Charles, chevalier de Folard (1669-1752), and Marshal Saxe,

whose Mes reveries is still read and admired today. During the Seven Years’ War,

the innovative Marshal-Duke Victor-Francois de Broglie, victor over Brunswick

at Bergen (13 April 1759), had introduced the all-arms division organization, a

necessary precursor of the larger Napoleonic army corps.

Thus, despite the stagnation and enervation so pronounced at

midcentury, it is not surprising that the French armed forces were reformed and

modernized during the reign of Louis XVI 1774-92 . The principal agent of reform

was the war minister. Claude Louis, comte de St. Germain (1707-78), who was

assisted in his work by Jacques Antoine Hippolyte. comte de Guibert (1743-90;

tactics and doctrine), Jean Baptiste Vaquette de Gribeauval (1715-89; artillery

materiel and organization), and Jean Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de

Rochambeau (1725-1807; tactics and infantry organization).

Although the old army was swept away in the Revolution

(1789), these reformers were directly responsible for creating the professional

core of the successful Revolutionary armies. However, the fine quality of the

reformed French army was already evident in 1780 in the small but magnificent

expeditionary corps that Rochambeau led to America and that played such an

important part in the Yorktown campaign.

Bibliography

Aumale, H. E. P. L. 1867. Les institutions militaires de France:

Louvois-Carnot- Saint Cyr. Paris: Levy. Dollinger, P. 1966. Histoire

universelle des armees. Vol. 2. Paris: Laffont. Kennett, L. 1967. The French

armies in the Seven Years’ War. Durham, N. C.: Duke Univ. Press. Susane, L. A.

V. V. 1974. Histoire de la cavalerie frangaise. 3 vols. Paris: Hetzel. . 1874.

Histoire de Vartillerie frangaise. Paris: Hetzel. . 1876. Histoire de

Vinfanterie frangaise. 5 vols. Paris: Dumaine. Weygand, M. 1953. Histoire de

Varmee frangaise. Paris: Flammarion.