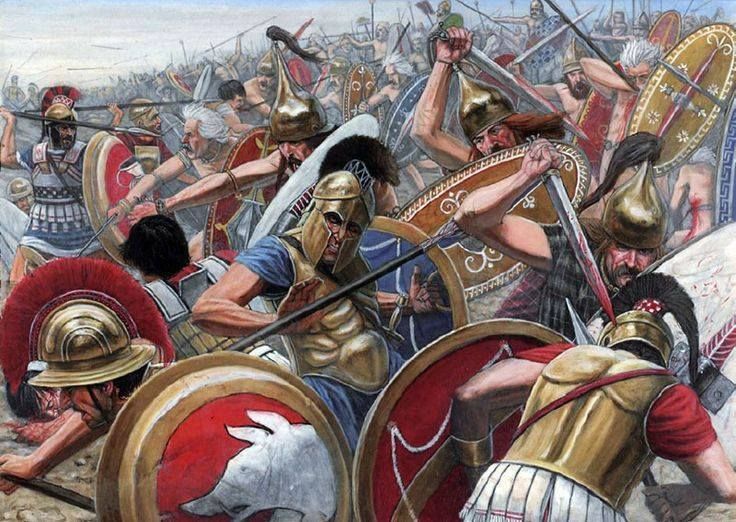

At the Battle of Allia, ‘mere barbarians’ defeated the Roman army and afterwards, sacked Rome.

The sack of Rome by the Gauls c. 390 BC represented a

‘watershed moment’ in early Roman history, after which nothing was quite the

same. This was the point identified by Livy as the ‘second birth’ (secunda

origine) of the city and the moment he selected as the starting point of his

second ‘pentad’ (set of five books) in his history. In other words, if Livy was

a Hollywood filmmaker making a series of movies about early Rome, the first

installation would have started with Aeneas and Romulus and culminated with the

city’s victory over Veii, and the second would start with the epic tragedy of

the Gallic sack and Rome’s rise to greatness in the century following. So, for

the Romans, the sack of Rome and the associated defeat at the River Allia

clearly represented a turning point in their history – although one whose

significance had changed and been adapted over time.

For Livy and the historians of the late Republic, the

primary significance of the sack of Rome seems to have been that it marked the

point at which evidence seemed to get a bit more reliable. At the start of book

6, Livy famously noted that ‘from this point onwards a clearer and more

definite account shall be given of the City’s civil and military history’. The

problematic nature of the evidence for the preceding centuries was usually

blamed on the destruction of records in a great fire caused by the sack,

although there is minimal archaeological evidence to support this. Livy hints

at this event though, saying the faulty data for the fifth century BC is in

part the result of an incensa, although the timing and nature of the fire is

disputed with some scholars arguing that it actually refers instead to a second

century BC fire at the regia – associated with the pontifex maximus, where

records were stored. For the rest of the Roman populace in the late Republic,

the Gallic sack seems to have marked a time of ill-omen, made famous by the

Dies Alliensis (Day of the Allia), which commemorated the defeat which led to

the sack, but probably little more than that – at least after Caesar’s conquest

of Gaul and the final removal of the great Gallic threat. However, in the context

of the period, the importance of the Gallic sack of Rome c. 390 BC cannot be

overstated. Although it probably did not produce any immediate changes in its

own right, despite the assertions of Plutarch and others, it did provide an

immense catalyst for change and accelerated the numerous social, political and

military developments which were already underway in Rome. Specifically, and

focusing on the Roman army, the victory by the Gauls sounded the final death

knell for the archaic clan-based warband as the primary military unit in Rome.

Although these continued to exist throughout the fourth century BC in various

parts of Italy, their ineffectiveness against the Gauls in 390 BC demonstrated

quite clearly to the Romans that their time was over. The trauma of the sack

also seems to have brought the Roman community together in a way it had never

experienced before. While previously the community had represented a slightly

amorphous and fluid population based around the urban centre of Rome, the

aftermath of the sack witnessed the true advent of a distinct Roman identity –

a ‘Romanitas’ or ‘Roman-ness’ – that would develop into the more concrete Roman

citizenship, which later Romans would prize so dearly. This new sense of

Romanitas would go on to drive the social and political developments of the

fourth century BC as well, including the end of the ‘Struggle of the Orders’.

But more importantly for the Roman army during this period, it would allow (or

perhaps force) the creation of a new set of military commanders (the consuls),

a more strategic approach to military actions based on conquest, a new approach

to captured land (citizen colonies) and eventually a new tactical formation

(the so-called ‘manipular legion’). In this context, the Gallic sack seems to

have pushed Rome over the edge of the cliff of social, military and political

development she had been walking along up to that point – venturing near it,

only to pull back and regress to her archaic modus operandi. The arrival of

Gauls in serious numbers in the early fourth century BC demonstrated that the

Romans would need to adapt or face utter destruction – and so adapt they did.

The Gallic Sack

The sack of Rome by the Gauls was the culmination of a

series of battles (and defeats) which are described in some detail by a huge

range of authors (Cato, Polybius, Livy, Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Diodorus

Siculus, Plutarch, Pliny the Elder, Pompeius Trogus, Appian and others). These

battles included an initial skirmish between members of the Fabii clan and the

Gauls near the city of Clusium, the major defeat of a combined Roman army at

the River Allia and finally the ‘siege’ and subsequent capture of at least most

of the city of Rome itself. There are also some accounts which suggest that

there was yet another battle after the sack, which the Romans are supposed to

have won, when the Roman general Camillus, who had been recalled from exile

during the siege, chased down the Gauls in order to recapture the gold paid as

an indemnity. This final (and incredibly dubious) battle aside, the Gallic sack

represented a comprehensive defeat of Rome’s armed forces which was done

without the benefit of surprise or an ambush. The sources are unanimous that

Rome’s forces were simply outmatched.

Although the details of the events vary quite a bit between

the surviving sources, and the archaeological evidence for the sack is (perhaps

surprisingly, given its supposed violence) almost non-existent, the capture of

the city by the Gauls represents one of the few aspects of early Roman history

which even the most suspicious of scholars can feel reasonably confident in.

First, and perhaps foremost, the sack of Rome by the Gauls seems to have left

an indelible mark on the Roman psyche, and created a longstanding cultural

‘bogeyman’, inspiring the metus Gallicus (‘Gallic fear’) which even Hannibal

and the metus Punicus (‘Punic/Carthaginian fear’) could not top. From this

period on, the Gallic menace arguably represented Rome’s greatest anxiety – one

which was only put to rest by Caesar and his campaigns in Gaul (an oft

forgotten aspect of his Bellum Gallicum). The date of the defeat at the River

Allia was remembered for centuries as a day of ill-omen and the fear of another

attack by the Gauls led to the immediate institution of the tumultus Gallicus,

a mass conscription in defence of the city, and indirectly to the creation of

Rome’s alliance network in the fourth century BC. The sack of Rome by the Gauls

also represents one of the first specific mentions of Rome in the historical

record, as it was recorded by Aristotle (preserved in Plutarch’s Life of

Camillus) along with a number of other late fourth century BC Greek writers.4

This was an event which reverberated even outside of Italy.

Out of the surviving sources for the sack, Livy offers the most

complete account and the most detail for the events leading up to it,

suggesting both an interest and familiarity with the story which may have

resulted from his upbringing in Patavium in Cisalpine Gaul. Livy’s account

indicates that the history of the Gauls in Italy goes back to the final years

of the sixth century BC when a group, under the command of the two nephews of

the Gallic chief Ambigatus, ventured out from their homelands in Southern Gaul

looking for land. One nephew, Segovesus, took his people into the Hercynian

highlands in Southern Germany but the other, Bellovesus, took his followers

south across the Alps into Northern Italy. Once there, Livy claimed that

Bellovesus and his people destroyed an Etruscan army near the River Ticinus and

founded the city of Mediolanium, modern Milan. After a few years, a group of

settlers left Mediolanium under the command of Etitovius and settled even

further south, near Brixia and Verona. This was followed by still further waves

of Gallic settlers who ventured further and further south, with the Libui,

Salluvi, Boii, Lingones and Senones all pushing into Etruscan and later Umbrian

land – settling in the region which would become Cisalpine Gaul. According to

Livy it was then the Senones, the last of the tribes to venture south from

Southern Gaul, which made its way to Rome under the leadership of Brennus,

before heading even further south to take up service as mercenaries under the

tyrant Dionysius I of Syracuse.

Undoubtedly based on local traditions in Cisalpine Gaul,

Livy’s account meshes well with what we know about the region archaeologically

and indirectly from other literary sources. It has long been established that

the late sixth and fifth centuries BC were hard times for the Etruscans, as

they came under increasing pressure from Gauls from the north along with the

decline of trade with the Greek communities of Magna Graecia, and this period

is generally seen as one of Etruscan decline – the beginning of the end of a

long period of dominance. The motivation for the Gauls’ movement south towards

Rome, at least as presented in Livy, is ambiguous though. The general narrative

which he presents of Gallic incursions ever further south into Italy is one

based on a desire for land, and Livy seems to imply that this was also true for

Brennus’ Gauls. This would suggest that Brennus was travelling with a large

group of Gauls, which likely included women, children, animals, etc., which was

bent on conquest or at least settlement – an interpretation which was also presented

by Polybius in his account of the event. However, there is also the ulterior

motivation of service in the court of Dionysius I of Syracuse as mercenaries.

This type of mercenary service was particularly common in the fourth century

BC, as numerous recent studies have illustrated, and southern Italy in

particular had a thriving mercenary economy. If this motivation represents the

actual one (and the circumstantial evidence suggests that it was), then Brennus

might not have been travelling with an entire tribe, including women and

children, but rather a group of warriors who were setting out to make their

fortune and then, perhaps, return home.

Whatever the actual makeup of the Gallic forces at Clusium,

Allia and Rome, they were undoubtedly effective and evidently defeated the

Roman forces in all three battles. At Clusium, this would not have taken much.

Livy reported that three members of the Fabian clan had been sent to Clusium as

ambassadors of Rome, but evidently joined the local forces and engaged in battle

against the Gauls. The forces of Clusium, along with the Fabii, were quickly

defeated, but this involvement by the Fabii supposedly provoked the Gauls into

attacking Rome, leading to the city’s eventual capture. While the reality of

this portion of the narrative is entirely uncertain, and may either represent

an anti-Fabian tradition (blaming them for the sack) or perhaps the activities

of an independent clan-based army which merely happened to get involved, after

defeating the forces of Clusium, the Gauls did evidently continue their march

south, meeting the forces of Rome at the River Allia. The Roman army which

faced off against them was led by six consular tribunes, including the three

Fabii from Clusium in addition to Quintus Sulpicius Longus, Quintus Servilius

and Publius Cornelius Maluginensis, and contained approximately 40,000 men.

While it is likely that this estimate is exaggerated, the actual number of

Romans present was clearly substantial, as the magnitude of the subsequent

defeat was deeply etched into the Roman consciousness. During the battle, the

Roman army was evidently spread thin in an attempt to match the frontage of the

much larger Gallic force and was quickly routed, with the remnants of the army

fleeing to both Rome and the recently captured city of Veii. After the defeat,

the Gauls entered Rome virtually unopposed, except for the defences on the

Capitoline. The sources then describe an epic siege of the Romans on the hill,

with the rest of the city burning below. Included in the larger siege narrative

is the famous anecdote of the geese, where the Gauls attempt to sneak up the

side of the Capitoline hill but in doing so startle the geese who lived there,

sacred to Juno, with the resultant noise alerting the Romans to the danger. In

honour of this, the Romans later founded a temple to Juno Moneta (moneta from

the Latin word monere, to warn) on the Capitoline, which ultimately became the

mint at Rome. Eventually, however, the Senate was forced to negotiate a truce

with the Gauls whereby they paid the Gallic leader Brennus 1,000lbs of gold.

What happened after the negotiations is slightly more

problematic. One tradition states that the Romans simply paid the indemnity.

This version often includes the anecdote that the Romans then discovered that

the Gauls were using heavier weights than the standard typically used for

weighing out the gold, but when the Romans complained Brennus supposedly threw

his sword on top of the scales and uttered the phrase ‘vae victis’ (‘Woe to the

conquered’) in response. However, Livy offers a different version, followed by

Plutarch, which claimed that while the Capitol was still besieged the Senate

appointed as dictator the exiled Roman noble Camillus, who eventually arrived

from Ardea with an army and, after summoning additional forces from Veii, went

on to defeat the Gallic forces before the ransom could be paid. Diodorus

provided another version in which the ransom was paid and the Gauls left the

city, only to be defeated in a separate battle at Veascium later that year by

Camillus, and the gold was then recovered. Polybius, meanwhile, offered yet

another version where the bribe was paid and the Gauls simply returned home, an

account which Livy actually supports in a later passage.

Camillus

An important, and yet incredibly enigmatic, figure in this

entire narrative is Marcus Furius Camillus (traditionally lived c. 446–365 BC).

Camillus, as he is commonly known, is probably one of the most important

figures in early Roman history and yet also one of the most obscure. Described

by Livy as a ‘second founder’ of Rome,5 an attribution which is supported by

Plutarch, Camillus dominates the narrative c. 400 BC, and plays the leading

role in both the siege and sack of Veii and Rome’s recovery from the Gallic

sack. His only notable absence is from the narrative of Rome’s defeat itself,

which is explained by his ‘exile’ just previous to that. He triumphed at least

four times and held the dictatorship five times, along with the consular

tribunate (multiple times) and the censorship – giving him a military and

political career which was truly remarkable during this period. Indeed, rather

like Tarquinius Superbus at the start of the fifth century BC, who seemed to

feature amongst Rome’s enemies in just about every battle, the figure of

Camillus is ubiquitous in the narrative, appearing in a leading role in almost

all of Rome’s victories (although he is conspicuously absent from her losses).

Intriguingly, however, not all of the surviving sources for

the early fourth century BC feature Camillus. Both Diodorus and Polybius, the

latter of which is often seen as one of the more reliable historians, largely

ignore Camillus and his achievements, which has led some scholars (when taken

along with his arguably unbelievable résumé) to suggest that not only was the

figure of Camillus exaggerated, he may have actually been largely invented. The

mid-twentieth century scholar Georges Dumézil, for instance, argued that

Camillus was not intended to be a historical figure at all but actually an

exemplum created by later writers, which he associated with a hero of the

goddess Aurora, who personified key Roman virtues during this period. Others

have taken a series of less extreme positions, but even the more optimistic

scholars have generally been forced to admit that the record for Camillus most

likely contains some significant elaboration. These points aside, it is clear

that Camillus represents an important figure in, at least, the Roman memory of

the period c. 400 BC. He seems to have embodied, somehow, the spirit or

‘zeitgeist’ of the time and his actions, however much they were exaggerated by

later storytellers and writers, were remembered as vital to Rome’s development.

Historicity aside, Camillus does represent quite a useful

figure in the narrative. As already noted, he was used in some versions of the

story to assuage Roman honour during and after the sack, by defeating the Gauls

and reclaiming Rome’s gold. He also represented a powerful catalyst for Rome’s

recovery, as his victories in the 380s, 370s and 360s BC drove a prolonged

period of Roman expansion and conquest. Camillus is an intriguing figure too in

the internal political debates which raged in Rome during the 370s and 360s BC.

Although a patrician and the most important figure in Roman politics at this

time, Camillus is also presented as a facilitator of concordia, or peace,

between the patricians and plebeians in the ‘Struggle of the Orders’, and

specifically in the ten years of political unrest between 376 and 367 BC.

Indeed, as a result of the concordia ordinum which Camillus achieved he is

supposed to have founded and dedicated a temple to Concordia in the forum. In

Livy’s narrative, which is our main source for this period (Dionysius’s history

being unfortunately fragmentary for these years), Camillus seems to represent

both sides in the debate at various times although, as Momigliano and others

have noted, his involvement is likely to represent, at least in part, a late

Republican attempt to rationalize the events. But it is exactly this ability to

represent both sides of a matter which makes him so appealing. Camillus is at

once an Archaic warleader who is evidently mobile (as seen by his exile and

subsequent return to power in Rome) and backed by a powerful gens (the Furii).

His power base and position therefore harken back to the fifth century BC and

the powerful, warlike raiding gentes which dominated the period. However, in

Rome he also occupies a prime position in the new, state-based system – acting

as both a consular tribune and censor, but never as a praetor. The closest he

comes to that position is as the dictator, a position which he holds multiple

times, and which might have served as the template for the later consulship.

Camillus is therefore a liminal or transitional figure in the narrative, which

both represents the old, archaic model of power and new, state-based way of

operating, which includes both the patricians and the plebeians.

Camillus’ role in Roman history c. 400 BC is therefore an

important one. Whether or not he represents a real figure (the evidence from

the fasti suggests that he was) and whether or not all of his achievements are

real (here the evidence is far from convincing), Camillus does seem to

illustrate an interesting phenomenon – the final integration of Latium’s

gentilicial elite into Rome’s social, political and military systems after the

Gallic sack. A previously mobile war leader, who may have been exiled (or

simply left for greener pastures), Camillus was invited to return to Rome in the

years following the sack of Rome and played a key role in the city’s return to

greatness. This hints that the urban community of Rome recognized that having a

figure like Camillus, along with his evidently powerful group of followers, was

important given the defeat by the Gauls. And it also suggests that figures such

as Camillus, despite the ‘old-fashioned’ or archaic nature of his power base,

found ways to make Rome’s new military and political system work for him as

well. For Camillus, this was largely done through the mechanism of the

dictatorship, but his role in establishing the concordia ordinum may also

suggest that this type of figure was increasingly finding areas to compromise

and establish a system which worked for both sides of the ‘Struggle of the

Orders’. So although the figure of Camillus is problematic in strictly

historical terms, he may illustrate some important developments in Rome during

this period – and the strongest evidence for this is how well his actions and

behaviour align with the rest of Rome’s reactions to the Gallic sack.

Rome’s Internal

Reaction

Rome’s invitation to Camillus to return to Rome, supposedly

issued while the Capitoline hill was still under siege by the Gauls, is

generally representative of Rome’s attitude during the years immediately

following the defeat. While the city and her increasingly stable collection of

clans/gentes had previously let local politics dominate and individual

ambitions dictate both domestic and foreign policy, in the years after the sack

Rome emerged with a new direction and drive. And, as with the recalling of

Camillus from Ardea, this direction was based on immediately securing and

expanding her military capabilities, probably in order to prevent a future

defeat by the Gauls. All previous squabbles were largely forgotten – this new

threat required a concerted effort from everyone.

Rome’s sudden, and entirely reasonable, interest in

expanding her military capabilities took a number of different forms. As

already noted, the recall of Camillus from his ‘exile’ in Ardea seems to have

been the first of these, but even this was part of a much larger attempt to

bring the clans who lived around the city together into a more stable union. As

suggested in the previous chapter, the powerful clans of Latium, and Central

Italy more generally, had already begun the long process of slowly settling

down and permanently associating themselves with various communities back in

the sixth and fifth centuries BC. This can be linked to changes in the economy

and an increased focus on land and agriculture, in addition to the rise of the

urban centres themselves. However, as the exile of Camillus indicates (and

whether this represented a true exile or merely the movement of a powerful clan

leader is still debatable), prominent figures were still able to move around

the region and retain most, if not all, of their power and influence,

suggesting that this process was ongoing. During the first half of the fourth

century BC, however, Rome saw the rise of a distinctive ‘Roman Nobility’ – or

group of clans who would go on to dominate Roman politics for the rest of the

Republican period, to the exclusion of others. Associated with the closing of

the patriciate in the second half of the fifth century BC, which marked the

establishment of a distinct ‘patrician’ group in Rome, the creation of the

‘Roman Nobility’, although still partly based on kinship, was predicated on a

new set of social norms where glory and social power were attained largely

through holding positions within Rome’s civic structure. Although obviously in

its infancy during this period, as scholars like Matthias Gelzer identified

back in the early twentieth century, the fourth century BC witnessed the

origins of a group, who were described as clarissimi or principes civitatis by

later sources, whose position was due almost entirely to their family history

of holding the key magistracies in Rome. Unfortunately, the nuances of the

earliest incarnation of this group are likely lost to us forever, given the

nature of the sources for this period, but this development seems to be the

result of the city developing a particular, mutually beneficial relationship

with certain families, whereby the longstanding competition which had existed

between them for glory was moved from outside the city – in the form of

raiding, mortuary practices, etc. – to inside the city, and a competition over

magistracies.

This relationship clearly benefited the community, as it

firmly linked the local clans and their military strength to the city for the

long term, but it is initially unclear what the advantage might be for the

clans. Although the clans which had settled around Rome would increasingly have

had their interests aligned with those of the community anyway, with the result

that maximising the military capabilities of the community would have also

benefited them, the continuing existence of mobile clans in Latium, who would

have been able to simply pick up and leave if the Gauls returned (as perhaps

Camillus did in 390 BC), suggests that this was not enough for everyone. The

result of this situation is yet another period of political tension within

Rome, and another flare up of the ‘Struggle of the Orders’, as the powerful,

rural clans and the urban community once again attempted to find some middle

ground. The default during the first half of the fourth century BC seems to

have been the use of the consular tribunate, with all that that entailed,

although the office of the dictatorship was also increasingly utilized,

seemingly as a short-term solution to this issue. The dictatorship allowed the

return of many of the Archaic prerogatives of the praetorship, including imperium

(and the associated right to triumph) and so would have been appealing to the

region’s gentilicial elite, but could be used alongside the consular tribunate

and therefore maximised Rome’s military might. However, it is clear that this

was a short-term solution and one which was not wholly satisfactory to either

side. As a result, in 367 BC, the Romans created a new magistracy as a

long-term fix: the revamped consulship.

Princeps, Eques, Velites

The Military Reforms

of Camillus

The next great landmark in Roman military organization is

associated with the achievements of Camillus. Camillus, credited with having

saved Rome from the Gauls and remembered as a “second founder” of Rome, was a

revered national hero. His name became a legend, and legends accumulated round

it. At the same time, he was unquestionably a historical character. We need not

believe that his timely return to Rome during the Gallic occupation deprived

the Gauls of their indemnity money, which was at that very moment being weighed

out in gold. But his capture of the Etruscan city of Veii is historical, and he

may here have made use of mining operations such as Livy describes. Similarly,

the military changes attributed to him may in part, if not entirety, be due to

his initiative.

Soon after the withdrawal of the Gauls from Rome, the

tactical formation adopted by the Roman army underwent a radical change. In the

Servian army, the smallest unit had been the century. It was an administrative

rather than a tactical unit, based on political and economic rather than military

considerations. The largest unit was the legion of about 4,000 infantrymen.

There were 60 centuries in a legion and, from the time of Camillus, these

centuries were combined in couples, each couple being known as a maniple

(manipulus). The maniple was a tactical unit. Under the new system, the Roman

army was drawn up for battle in three lines, one behind the other. The maniples

of each line were stationed at intervals. If the front line was forced to

retreat, or if its maniples were threatened with encirclement, they could fall

back into the intervals in the line immediately to their rear. In the same way,

the rear lines could easily advance, when necessary, to support those in front.

The positions of the middle-line maniples corresponded to intervals in the

front and rear lines, thus producing a series of quincunx formations. The two

constituent centuries of a maniple were each commanded by a centurion, known

respectively as the forward (prior) and rear (posterior) centurion. These

titles may have been dictated by later tactical developments, or they may

simply have marked a difference of rank between the two officers.

The three battle lines of Camillus’ army were termed, in

order from front to rear, hastati, principes and triarii. Hastati meant “spearmen”;

principes, “leaders”; and triarii, the only term which was consistent with

known practice, meant simply “third-liners”. In historical accounts, the

hastati were not armed with spears and the principes were not the leading rank,

since the hastati were in front of them. The names obviously reflect the usage

of an earlier date. In the fourth century BC the two front ranks carried heavy

javelins, which they discharged at the enemy on joining battle. After this,

fighting was carried on with swords. The triarii alone retained the old

thrusting spear (hasta). The heavy javelin of the hastati and principes was the

pilum. It comprised a wooden shaft, about 4.5 feet (1.4m) long, and a

lancelike, iron head of about the same length as the shaft; which fitted into

the wood so far as to give an overall length of something less than 7 feet

(2.1m). The Romans may have copied the pilum from their Etruscan or Samnite

enemies; or they may have developed it from a more primitive weapon of their

own. The sword used was the gladius, a short cut-and-thrust type, probably

forged on Spanish models. A large oval shield (scutum), about 4 feet (1.2m)

long, was in general use in the maniple formation. It was made of hide on a

wooden base, with iron rim and boss.

It has been suggested that the new tactical formation was

closely connected with the introduction of the new weapons. The fact that the

front rank was called hastati seems to indicate that the hasta, or thrusting

spear, was not abandoned until after the new formation had been adopted.

Indeed, cause and effect may have stood in circular relationship. The open

formation could have favoured new weapons which, once widely adopted, forbade

the use of any other formation. At all events, there must have been more elbow

room for aiming a javelin.

Apart from these considerations, open-order fighting was

characteristic of Greek fourth-century warfare. Xenophon’s men had opened ranks

to let the enemy’s scythe-wheel chariots pass harmlessly through. Agesilaus

used similar tactics at Coronea. Camillus was aware of the Greek world – and

the Greek world was aware of him. He dedicated a golden bowl to Apollo at

Delphi and Greek fourth-century writers refer to him. It is at least possible

that the new Roman tactical formation was based on Greek precedents, as the old

one had been.

Officers and Other

Ranks

The epoch of Camillus also saw the first regular payments

for military service. The amount of pay, at the time of its introduction, is

not recorded. To judge from the enthusiasm to which it gave rise and to the

difficulty experienced in levying taxes to provide for it, the sum was

substantial. It was a first step towards removing the differences among

property classes and standardizing the equipment of the legionary soldier. For

tactical purposes, of course, some differences were bound to exist: for

instance, in the lighter equipment of the velites. But the removal of the

property classes produced an essential change in the Roman army, such as the

Greek citizen army had never known. The Athenian hoplites had always remained a

social class, and hoplite warfare was their distinctive function. The Spartan

hoplites had been an élite of peers, every one of them, as Thucydides remarks,

in effect an officer.

At Rome, however, the centuries of which the legions were

composed were conspicuously and efficiently led by centurions, men who

commanded as a result of their proven merit. The Roman army, in fact, developed

a system of leadership such as is familiar today – a system of officers and

other ranks. Centurions were comparable to warrant officers, promoted for their

performance on the field and in the camp. The military tribunes, like their

commanding officers, the consuls and praetors, were at any rate originally

appointed to carry out the policies of the Roman state, and they were usually

drawn from the upper, politically influential classes.

Six military tribunes were chosen for each legion, and the

choice was at first always made by a consul or praetor, who in normal times

would have commanded two out of the four legions levied; as colleagues, the

consuls shared the army between them. Later, the appointment of 24 military

tribunes for the levy of four legions was made not by the consuls but by an

assembly of the people. If, however, additional legions were levied, then the

tribunes appointed to them were consular nominations. Tribunes appointed by the

people held office for one year. Those nominated by a military commander

retained their appointment for as long as he did.

Military tribunes were at first senior officers and were

required to have several years of military experience prior to appointment. In

practice, however, they were often young men, whose very age often precluded

them from having had such experience. They were appointed because they came from

rich and influential families and they thus had much in common with the

subalterns of fashionable regiments in latter-day armies. Originally, an

important part of the military tribune’s duties had been in connection with the

levy of troops. In normal times, a levy was held once a year. Recruits were

required to assemble by tribes (a local as distinct from a class division). The

distribution of recruits among the four legions was based on the selection made

by the tribunes.

“Praetor” was the title originally conferred on each of the

two magistrates who shared supreme authority after the period of the kings. The

military functions of the praetor are well attested, and the headquarters in a

Roman camp continued to be termed the “praetorium”. In comparatively early

times, the title of “consul” replaced that of “praetor”, but partly as a result

of political manoeuvre, the office of praetor was later revived to supplement

consular power. The authority of a praetor was not equal to that of a consul,

but he might still command an army in the field.

The command was not always happily shared between two

consuls. In times of emergency – and Rome’s early history consisted largely of

emergencies – a single dictator with supreme power was appointed for a maximum

term of six months, the length of a campaigning season. The dictator chose his

own deputy, who was then known as the Master of the Horse (magister equitum).

The allies, who were called upon to aid Rome in case of war,

were commanded by prefects (praefecti), who were Roman officers. The 300

cavalry attached to each legion were, in the third century BC at any rate,

divided into ten squadrons (turmae), and subdivided into decuriae, each of

which was commanded by a decurio, whose authority corresponded to that of a centurion

in the infantry.