Hyazinth Graf Strachwitz Von Gross-Zauche Und Camminetz was

the most decorated regimental commander, and one of the most effective panzer

leaders, in the German Army.

He was one of only 27 men in the entire Wehrmacht to be

awarded the Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds. Of these he

was the only one to receive grades of the decoration for both bravery and his

command abilities, which led to the significant outcomes which merited the

award. The other Diamonds recipients received awards for either their bravery

and combat accomplishments, such as Erich Hartmann for his 352 aerial victories,

or for their skill in command, such as Hans Hube and Walter Model. In the

latter cases their men did the actual fighting and the award was as much for

the units under their command as for them.

Von Strachwitz’s rapid rise during World War II from a lowly

captain to a lieutenant general, equivalent to a major general in the UK and US

armies, was nothing short of extraordinary, and this in an army not lavish in

granting promotions.

He fought in nearly all of the major campaigns—the invasions

of Poland, France and Yugoslavia, and the important campaigns and battles in

the east including Operation Barbarossa, the battles of Kiev, Stalingrad,

Kharkov, and Kursk, the Baltic States and finally of Germany and his beloved

Silesia—his service being almost a microcosm of World War II in Europe. In the

course of these battles, not only did he win renown—becoming a legend among

those who fought on the Eastern Front who gave him the title Panzer Graf

(Armoured Count)—but was also wounded 14 times, probably was probably unique

amongst the ranks of Germany’s senior officers and a testament to his leading

from the front.

Such an extraordinary record of courage and command would

have made him unique in any army of World War II. Yet he is a man of mystery,

with very little known about him and nothing of substance yet been written. He

is mentioned in countless books, articles and websites, but at most is only

given a brief biographical outline, and even this is often inaccurate in parts.

Günter Fraschke wrote a German-language biography in 1962, which, if largely

factual, was nevertheless discredited for its inaccuracies and sensationalism

and rejected by the Panzer Graf himself.

Unfortunately the Panzer Graf himself wrote no memoirs; left

no diary, and any notes and papers were lost along with his home in 1945. His

records of service in the 16th Panzer Division were destroyed along with the

division in the battle of Stalingrad in 1943. After a period of distinguished

service with the elite Grossdeutschland Division, he served as commander of

several ad-hoc units, some bearing his name, in a period when records, if kept

at all, were scanty, or lost. It all makes for a rather threadbare paper trail.

His comrades-in-arms have now all passed away, so there are no witnesses to his

many battles and exploits.

#

After the Battle of Kursk, it took the Graf several months

to recover from his wound, including weeks of convalescent leave. The question

then arose as to his deployment. It seems clear that he did not wish to return

to the Grossdeutschland Division, and General Hörnlein equally did not want him

back. The two did not got on, and the Graf had not covered himself with glory

at Kursk as he had done in previous battles. Nevertheless the Panzer Graf’s

undoubted talents could not be wasted. A divisional command was the next step

for him, which meant that he was under consideration to take over the Panzer

Lehr Division. This superbly equipped formation had been established from

demonstration and training units trialing and demonstrating new weapons and

tactics. All its infantry regiments were mechanized with armoured personnel

carriers while its equipment tables were far more lavish than that for a

standard panzer division, which for instance only had one battalion equipped

with APCs with the remainder being truck borne, and here also both APCs and

trucks were often in short supply.

He didn’t get this command, which instead went initially to

Fritz Bayerlein. This may have been for several reasons. The least favourable

was that the Graf’s personality, outlook and tactical approach did not make him

suitable for a standard divisional command, which required a great deal of

preoccupation with logistical and administrative matters as well as controlling

a diverse range of formations not necessarily connected with direct combat,

such as signals, transport, supply, medical, engineering and administration.

Perhaps von Strachwitz was considered too much a hands-on front-line combat

commander to have his abilities diverted by the numerous non-combat tasks often

required of a divisional commander. Equally, tying down such an

independent-minded commander to the chains of divisional and corps structures

would not be the best use of his talents. Being independent with a regiment was

a far cry to acting independently with a whole division. Perhaps the deciding

factor was that the Graf could be better used for special missions or in a fire

brigade role. His skill clearly lay in achieving a great deal with very little.

He was one of the few commanders who could make a very real difference through

his sheer presence and ability. Putting it bluntly, any reasonably competent

general could achieve fair results with a well-equipped panzer division.

However, very few commanders could manage a superlative result with little or

few resources.

In any event, he was passed over for Panzer Lehr. The

division was later deployed in Normandy, and had von Strachwitz been in command

it might well have caused the Allies more difficulties than it did under its

actual commander, General Fritz Bayerlein, a dilettante who had established his

reputation as Erwin Rommel’s Chief-of-Staff in North Africa. His handling of

Panzer Lehr during the Allied invasion of France was average, bordering on the

lacklustre. He displayed none of the flair and imagination of von Strachwitz or

other commanders such as Bäke, von Manteuffel or Raus, so that the superb

division underachieved under his control. Later, during the Ardennes Offensive,

Hasso von Manteuffel, Bayerlein’s army commander, went to great lengths, to

avoid promoting him to command the XLVII Panzer Corps after its commander,

General von Luttwitz, had mishandled it, being held up unduly at Bastogne.

Bayerlein, as the senior divisional commander, was next in line to command a

corps but, unwilling to make the promotion, von Manteuffel left well enough

alone, a scathing indictment of Bayerlein.

So in April after being awarded the Swords to his Knight’s

Cross as the twenty-seventh recipient, Graf von Strachwitz was sent to Army

Group North, which had been grossly under-resourced almost since its inception.

Of all the army groups, its performance in achieved objectives could be

considered the most successful, despite getting little in the way of resources

or reinforcements, especially in armoured fighting vehicles. The Russians

themselves admitted after the war that Army Group North had fought the hardest,

especially when compared to Army Group Centre in the later years.

In January 1944 the Soviets launched their

Leningrad-Novgorod offensive, pushing the Germans back to the River Nava. They

hoped to annihilate Army Detachment Narva and sweep through Estonia, utilising

it as a base for a quick thrust into East Prussia. This army detachment, a

euphemism for an understrength army, comprised seven infantry divisions, one

panzer-grenadier division and three Waffen SS divisions of European

volunteers—11th SS Panzergrenadier Division Nordland, 4th SS Panzergrenadier

Division Nederland and the 20th SS Estonian Division—along with sundry smaller

units including Estonian border guards and the wholly German 502nd Heavy Panzer

Battalion under Major Jahde. The foreign volunteer SS divisions performed

heroically at Narva, accumulating no fewer than 29 Knight’s Crosses. The 502nd

Heavy Panzer Battalion, with 70 Tigers, was a highly effective unit with

several tank aces, including Lieutenant Otto Carius (150 tanks destroyed),

Lieutenant Johannes Bölter (139 tank kills), Albert Kerscher (106 kills),

Johann Muller and Alfredo Carpaneto (50 kills each). Its total kills for the

war were 1,400 Russian tanks of all types, for a loss of only 107 Tigers, a

kill/loss ratio of 13.08:1, the second best kill/loss ratio of any Tiger

battalion after Grossdeutschland’s battalion which achieved 16.676:1.3 Bölter

and Carius were originally NCOs who had climbed through the ranks. This was one

of the factors of the German Army’s success, promoting a great number of

officers from the ranks of distinguished NCOs, with officer candidates having

to serve in the ranks to prove themselves.

The Soviets’ winter offensive was successful in breaking the

900-day siege of Leningrad on 27 January, with the Germans making such a hasty

withdrawal that they left behind 85 guns which had been shelling the city. Two

German divisions were destroyed with the Russians capturing 1,000 prisoners and

30 tanks. After a period to regroup the Soviets resumed their offensive in

February, forcing the Germans back to the Panther Line, which was more illusion

than a fortified defensive line. The Germans now stood on the River Narva in

Estonia to await the next Soviet onslaught. Here, the III SS Panzer Corps, led

by the redoubtable SS General Felix Steiner, set up defensive positions across

11 kilometres east of the town of Narva. It would be the scene of intensely

savage fighting.

The Russian Eighth Army did, however, manage to establish

two bridgeheads across the river on 23 February, which became known as Eastsack

and Westsack. These threatened to unhinge the German line. The Germans had very

little in the way of armour to eliminate them, with the 502nd Heavy Tank

Battalion deploying four Tigers against Westsack and two against the Eastsack.

On that day the battalion destroyed its 500th Russian tank. The battalion’s 2nd

Company alone destroyed 38 tanks, four assault guns and 17 other guns between

17 and 22 March.

Although the Germans lacked a large armoured force they did

have the Panzer Graf, who could achieve more with a handful of tanks than any

other commander in the German Army. Hitler also sent General Model to take over

Army Group North without any reinforcements. When asked what he had brought

with him he confidently replied “Why, only me gentlemen.” So the Panzer Graf

was not the only one expected to perform miracles. Perform miracles they both

did. The Graf was initially promised three divisions, which would have made him

feel confident about his task, but they never arrived. Along with the promise

of panzers the Graf was given the grandiose title of armour commander of Army

Group North which would have been more impressive had he any sizeable armoured

formations to command. As it was he had to make do with what was available: the

502nd Heavy Tank Battalion with just 12 Tigers still operational, Battle Group

Böhrendt with a few assault guns and Panzer IIIs, units of the Feldernhalle

Division with a few Panthers, and some Panzer IVs from the SS Nordland

Division. His infantry was supplied by Grossdeutschland’s Fusilier Regiment

mounted in APCs. Grossdeutschland also provided some tanks and Nebelwerfer

rocket launchers. As a last-minute reinforcement Hitler sent over a battalion

from his escort brigade, which was literally the last reserve he had available.

The Russians had entire armoured and infantry corps sitting idly in reserve

while the Germans could only scrape up a battalion that wasn’t urgently needed,

so parlous had the German manpower and weapons situation become.

The Graf’s mission was to eliminate the Soviet Narva

bridgeheads. His actions have been generally categorized as operations

Strachwitz I, II and III. He chose the Westsack for Strachwitz I and spent a

great deal of time preparing for it. As always, good reconnaissance was

paramount along with intelligence from radio intercepts and prisoner

interrogations. Most prisoners, including officers, were willing to talk, as

were German captives, the very real fear of being executed proving a strong

motivating factor. Leaving nothing to chance he also had his troops rehearse

the attack. The training exercises were conducted with live ammunition with

several casualties incurred as a result. Careful reconnaissance led him to give

the Tigers a secondary supporting role due to the marshy nature of the terrain.

He had to rely on his lighter Panthers, Panzer IVs and assault guns for the

spearhead. After careful consideration von Strachwitz decided to attack

Westsack from the west. He reasoned, correctly, that the Russians would be

expecting an attack from the east as this had a good road and the German

artillery had good observation points from the nearby Blue Hills. As well, a

regiment of the German 61st Infantry Division was entrenched in a salient

there, called the boot.

At 5:55 a.m. on 26 March, von Strachwitz launched his attack

on the Westsack. It was preceded by, for what was for this period of the war, a

heavy artillery and Nebelwerfer barrage. The panzers followed, supported by the

infantry of Grenadier Regiments 2,44 and 23 from the East Prussian 11th

Infantry Division, a hard-fighting unit commanded by General Lieutenant Helmuth

Reymann. Eight Tigers had been ordered to support the infantry but they were

forced to withdraw due to the softness of the ground. The Graf’s decision not

to use the Tigers at the forefront had proven correct.

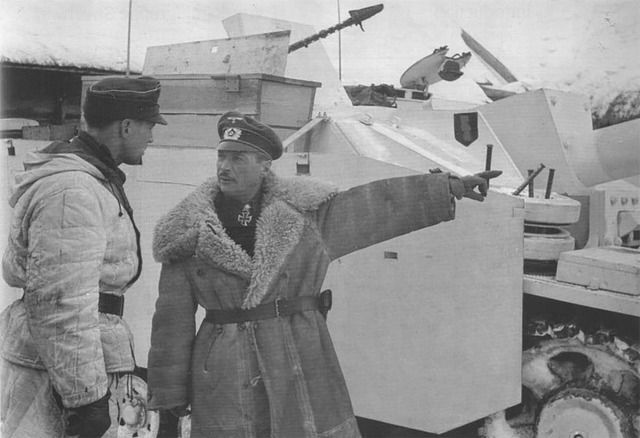

Ferocious fighting took place in the trackless swamps and

forests with heavy casualties on both sides. The German officer losses were

especially severe with all platoons and most companies being led by surviving

NCOs. The Graf led from the front as usual, a familiar figure in his bulky

sheepskin coat, bringing chocolates and cognac to comfort and encourage his

troops. He also brought with him several Iron Crosses Second Class, which he

awarded on the spot to the best fighters. When not accompanying him, his

adjutant Lieutenant Famula was close behind ensuring that ammunition, food and

fuel arrived on time wherever they were needed.

So vital was this operation that the Graf received Stuka

support, a fairly rare event given the stretched resources of the Luftwaffe.

This proved a mixed blessing however, with one bomb landing on the narrow track

on which the German tanks were advancing. One minute later and it would have

wiped out von Strachwitz himself. The Stuka pilots had great difficulty in

finding their targets amongst the trees, and the bombs were less than effective

in the forested terrain.

Early progress was good with a large number of prisoners

taken, but the Russians were not prepared to give ground easily. On 27 March

they counterattacked, pushing the Germans back with their first onslaught. They

continued their attack into the night. This led to some very frightening

close-quarter combat in the pitch-black woods. The next morning the Russians

commenced a sustained artillery bombardment causing heavy casualties, many

caused by the wood splinters from the fractured trees, so that companies of

normally over 100 men were reduced to platoons of fewer than 30. Von Strachwitz

summoned reinforcements, but they too suffered heavily from the Soviet

artillery fire, arriving already badly depleted.

Immediately after the artillery barrage the Russians sent in

their infantry in massed attacks which penetrated the thinly manned German

defences at several points. The Luftwaffe sent in ground-attack aircraft but

failed to dislodge the Russians. Several batteries of Nebelwerfers added their

weight to the fire, blasting the Russian positions in a crescendo of shattering

explosions. The Graf then ordered a counterattack, which threw the demoralised

Russians back with cold steel. He pushed forward with everything he had to

maintain the momentum. The Russians fought back tenaciously, but were steadily

forced to give ground. When driven out of their trenches their resistance

turned into a precipitous retreat with many surrendering. The retreat turned

into a rout. They left behind some 6,000 dead and 50 guns, along with the large

quantities of equipment on the battlefield. In addition, the Germans took some

300 prisoners. Against those Soviet losses the Germans suffered 2,200 dead or

missing. It was a superb if costly victory at a time when the Germans were in

retreat, or barely holding on along the rest of the front.

On 1 April Hyazinth von Strachwitz was promoted to the rank

of major general. For a colonel of the reserve this was a very unusual

promotion, and may have been unique. His monthly salary increased by around

50%. He wasn’t as fortunate as some generals, General Guderian for instance,

who received a large amount each month on top of his ordinary salary as a

personal gift from Adolf Hitler. Other generals and field marshals, such as von

Kluge, also received monetary gifts, as well as landed estates.

The Panzer Graf’s next operation was Strachwitz II, the

elimination of the Eastsack bridgehead. He knew the Russians were expecting him

to attack as he had attacked the Westsack. So he did the opposite, attacking at

East-sack’s northern tip to surprise them. This attack also took meticulous

preparation, which was becoming his trademark. As Otto Carius stated in his

memoir, Tigers in the Mud, regarding the planning for Strachwitz III, “his

careful, methodical planning amazed us once again” and that “the Graf was a

master of organisation.” This would seem at odds with his devil-may-care

cavalrymen’s approach, but it shows that, despite his reputation for dashing

raids and slashing cavalry-style attacks, he was a calm calculating man, and it

was this, together with his boldness, that made him such a formidable commander

and adversary.