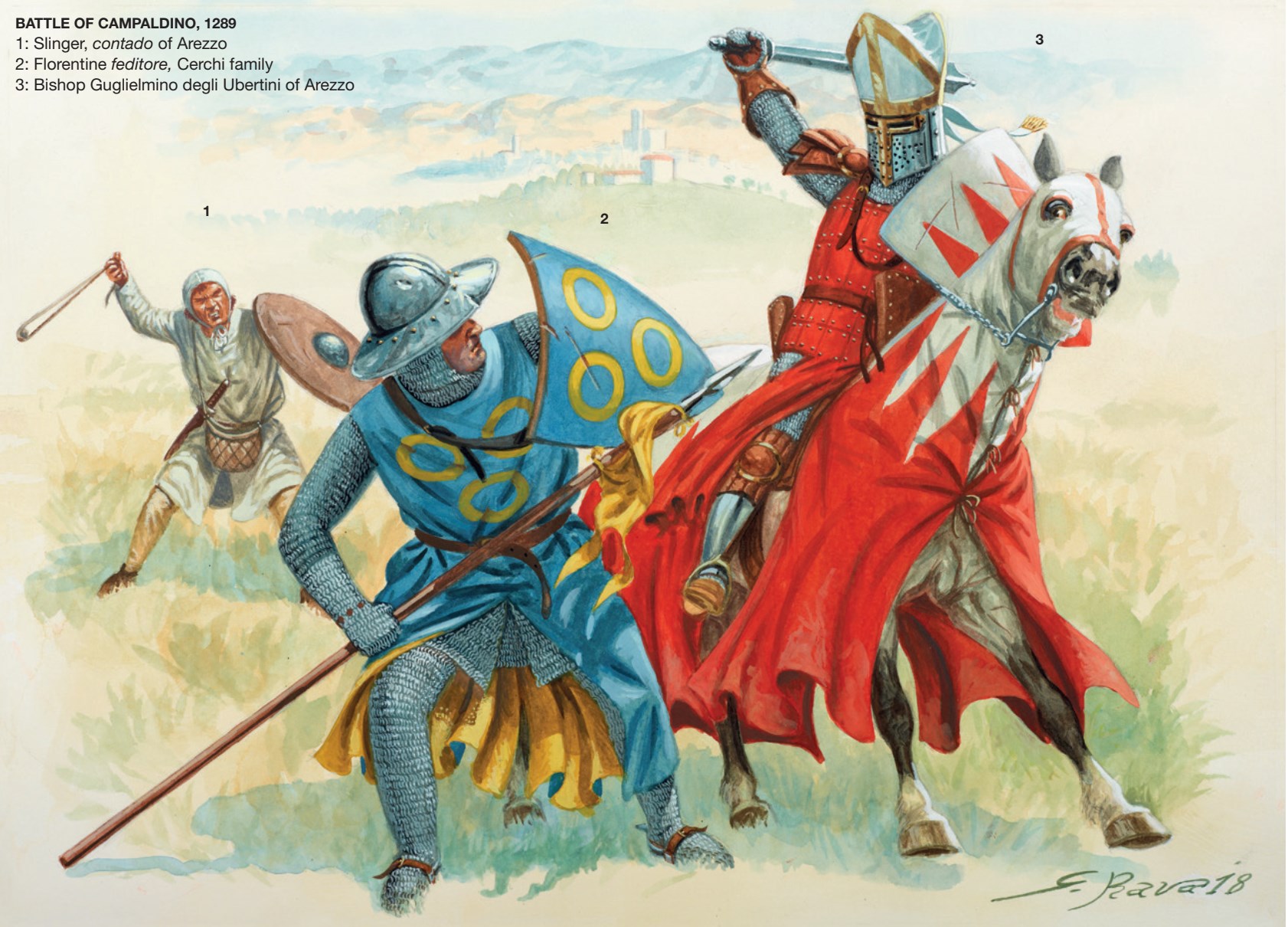

The military commander of the Ghibellines in this battle was

the city’s powerful bishop, Guglielmino degli Ubertini. Note two features

distinctive of ecclesiastical leaders who went to war in person: the crest on

his helm fashioned as a bishop’s mitre, and his use of a mace (mazza ferrata)

rather than a sword. The latter was a cynical ploy adopted to get around the

religious prohibition on churchmen `shedding blood’: they could kill enemies,

but only `sine effusione sanguinis’. The second half of the 13th century saw

the development of plate armour elements worn in combination with the mail

hauberk. Initially plate armour was mostly made of cuir bouilli (boiled,

moulded and hardened leather); here, this material is used for the domed

defences mounted on quilted cuisses at the knees, at the shoulders above

leather strips, and for the gauntlet cuffs, but the greaves on the lower legs

are already in metal. The mail hood worn under the helm was now a separate

camail. Over the hauberk the bishop wears a `coat-of-plates’, called in Italian

a lameria; buckled on at the back, this is a tabard-shaped garment made of

small iron plates riveted between two layers of thick fabric in such a way as

to allow some flexibility of the torso. Apparently, these lamerie were first

introduced in Italy on a large scale by the German mercenary knights employed

by Manfred of Swabia.

At a first glance, Guglielmino degli Ubertini would appear

to fit the stereotypical worldly clergyman of literature. While there is no

doubt that he often practised power mongering to a high degree in his more than

40 years as bishop of Arezzo (1248-89), switching his allegiance at will from

Guelph to Ghibelline, he always had in mind the interests of his city and his

diocese – at least when he saw them coinciding with his own and those of his

family. A man of the sword as much as of the pen, at the battle of Montaperti

in 1260 Ubertini led the exiled Aretine Ghibellines against the Guelph

coalition besieging Siena `capturing and killing many’. On a number of

occasions he did not hesitate to use the weapon of ecclesiastical censure

against his fellow citizens to obtain his political goals. As a military leader

he would show his limits during the 1289 campaign, when concerns over his own

possessions in the Casentino area led him to seek battle at all costs, despite

being advised otherwise. At Campaldino he demonstrated his attachment to his

native city, not hesitating to join the fray even when given the chance to

escape from the slaughter.

Guglielmo Ubertini who had served for forty years as the

bishop of Arezzo by the time of the battle. “A man of the sword as much as

of the pen”, Ubertini had proven to be capable, ruthless and brave

military commander during several conflicts before 1289, though his strategic

acumen was impeded by his interest in defending the possessions of his family

at any cost. This greatly influenced his decision to seek battle at Campaldino,

despite having been advised against it.

BATTLE OF CAMPALDINO, 1289

A Tuscan Guelf League army, mainly composed of Florentines,

faced a Ghibelline League force from Arezzo in the Amo valley. The Florentine

army appeared to be on the march for Arezzo along the well-worn road of the

Upper Valdarno, when all at once they swung to the left and crossed the Consuma

Pass without encountering any opposition, and entered the Casentino-the highest

valley of the river Arno. From there they descended towards Arezzo.

At first the local forces fell back before them, but they

eventually called a halt in the wide valley immediately north of Poppi after being

reinforced by the Ghibellines of the Romagna and the Marche.

The Tuscans, consisting of 1,600 cavalry and 10,000 infantry

(including a large number of crossbowmen), drew up with cavalry in the centre

and the bulk of their infantry formed up on both flanks slightly in advance of

the cavalry, thus constituting the horns of a crescent formation. The centre

was covered by a detached screen of light cavalry. Behind the whole array a

line of wagons was drawn up, behind which was positioned a reserve of 200

cavalry plus some infantry. (The poet Dante fought in the front rank of the

Florentine cavalry.)

The Ghibellines formed up in 4 lines with their 800 cavalry divided

between the first, second and last lines while their 8,000infantry, with a few

crossbows among them, made up the third. They opened the battle with a charge

which, although it routed the Florentine light cavalry and drove the Tuscans

back to their baggage wagons, committed their first three lines, the flanks of

which were then subjected to a devastating crossfire from the crossbowmen on

the Tuscan wings while the rest of the infantry, armed with long spears, closed

in around them. The Ghibelline reserve line of just 50 horsemen was never

committed and eventually fled, at which the Tuscan reserve came in on the rear

of their disorganised first lines, which were thus trapped. Ghibelline

casualties totalled 1,700 killed and 2,000 captured.

Throughout most of this period archers were present on the

battlefield in relatively small numbers. They and crossbowmen were usually

positioned on the flanks of the army in separate units with spearmen in the

centre, though they are also to be found skirmishing ahead of the main body, or

else interspersed with other infantry. Archers on the left of the line, firing

into the enemy’s unshielded flank, would have been particularly effective, and

with archers on both flanks it was possible to achieve a crossfire, as did the

Tuscan crossbowmen at Campaldino in 1289.

Suggested reading:

General Works: Villaripi, I primi due secoli della storia di Firenze, Florence,

1910, Davidsohn: Geschichte ion Florenz, Vol. IL Firenze. On the Campaign:

Koehler, G., Die Entwickelung des Kriegswesens und der Kriegfuhrung in der

Ritterzeit, Book III, Breslau, 1889. On the Battle: Fieri, P., ‘Alcune

quistioni sepra la fanteria in Italia nel periodo comunale’, in Rivista Storica

Italiana, 1934.