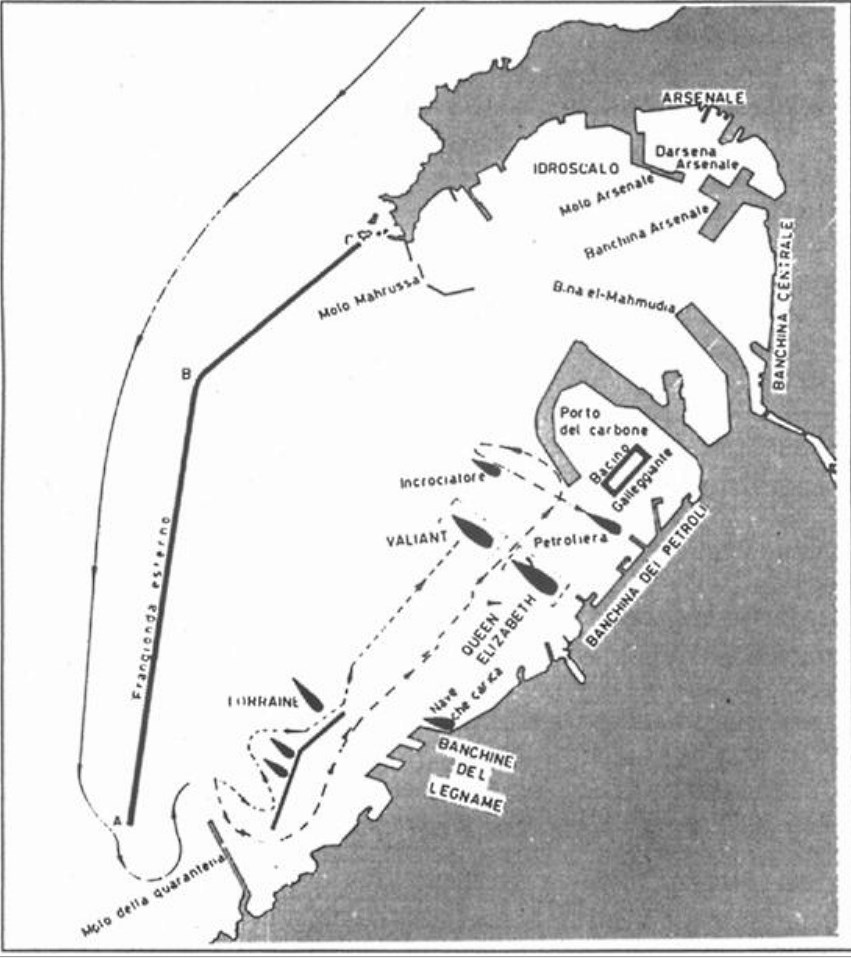

Routes of the Three Manned Torpedoes (Petroliera is the tanker Sagona.)

From de Risio, I Mezzi d’Assalto, 123

Critique

Were the objectives worth the risks? The Italian navy,

although beaten badly in the months prior to the attack on Alexandria, was in

the process of commissioning three new battleships, Doria, Vittorio Veneto, and

Littorio. The British had also suffered several naval defeats with the loss of

the aircraft carrier Ark Royal and the battleship Barham in November 1941. If

the Italians could destroy the remaining two battleships, Queen Elizabeth and

Valiant, they, along with the Germans, could dominate the Mediterranean. As it

stood, however, even with its numerical superiority, the Italian fleet was

insufficient to challenge the British in the eastern Mediterranean. With the

British still controlling the vital sea-lanes, the Italians had to struggle to

resupply Rommel’s forces in North Africa. By using the manned torpedoes to

conduct underwater guerrilla warfare, the Italians were able to make maximum

use of their maritime resources. With the destruction of two battleships and a

destroyer, the Italians had an opportunity to control the maritime playing

field and propagandize about the “weakness” of the British. Unfortunately, they

did neither. Nevertheless, when one considers that only six men and three

manned torpedoes were used to destroy the targets, the objectives were undeniably

worth the risk.

Was the plan developed to maximize superiority over the

enemy and minimize the risk to the assault force? The development of the manned

torpedoes was a technological revolution in underwater warfare. It allowed the

Italians to circumvent the conventional submarine marine defenses protecting

the capital ships and to bypass the picketboats that were specifically designed

to stop frogmen and divers. Superb operational intelligence allowed the

planners to tailor the rehearsals to the mission and thereby ensured that the

manned torpedo crews were properly prepared to overcome most obstacles.

Although the plan maximized the possibility that the battleships would be

destroyed, it did not minimize the risk to the divers. Unlike the attacks on

Gibraltar, in which the divers could hit the target and swim to neutral Spain,

there was little chance the Alexandria divers would return from a trip deep in

enemy territory. The Scire, which would have provided the best extraction

platform, departed immediately after launching the torpedoes. This reduced the

submarine’s vulnerability, but certainly did not help the manned torpedo crews.

There was an escape and evasion plan, but it was not well thought out and the

divers did not truly expect to return.* Although this one-way trip may seem

unacceptable by today’s standards, the Italians were able to maximize their

combat effectiveness by eliminating the extraction phase. The torpedo’s battery

power, the air in their Belloni rigs, and their physical endurance were all

dedicated to mission accomplishment and not saved for escape.

Was the mission executed according to the plan, and if not,

what unforeseen circumstances dictated the outcome? With some minor exceptions,

the plan was executed exactly as rehearsed. Schergat said later, “From my point

of view, the mission looked just like further training.” However, several

problems arose that typify the frictions of war. Durand de la Penne lost his

second diver, Bianchi, when the petty officer fainted and floated to the

surface. One of the three manned torpedoes took on too much ballast and sank to

the bottom of the harbor. One of the officers, Martellotta, got violently ill

and had to direct the actions of his torpedo from the surface. All of these

incidents were happenstance, but that is the nature of war. Regardless of how

well the planning and preparation phases go, the environment of war is

different from the environment of preparing for war. But, by being specially

trained, equipped, and supported for a specific mission, special forces

personnel can reduce those frictions to the bare minimum and then overcome them

with courage, boldness, perseverance, and intellect—the moral factors.

What modifications could have improved the outcome of the

mission? The success of the mission speaks for itself. However, it is

conceivable that had a more thorough escape and evasion plan been arranged, two

of the crews might have escaped. By prepositioning an agent and a small boat

outside the harbor, the evading crews could have quickly linked up and sailed

away from the scene before the demolitions exploded. Apparently, this was never

addressed. The Italians did have an agent in Cairo who was supposed to assist

the divers in their escape, but the Italians, being unfamiliar with the city

and unable to speak the language, had little chance of reaching this

individual. This part of the plan notwithstanding, the operation was extremely

well planned and coordinated, and there are very few modifications that could

have improved the outcome.

Relative Superiority

Operations that rely entirely on stealth for the successful

accomplishment of their mission have inherent weaknesses; however, they have

one overwhelming advantage. As long as the attacking force remains concealed,

they are not subject to the will of the enemy. Therefore their chances of

success are immediately better than 50 percent because the inherent superiority

of the defense is lost. The attacking force has the initiative, choosing when

and where it wants to attack, and if the mission is planned correctly, the

force will attack at the weakest point in the defense. Consequently, if the

will of the enemy is not a factor, only the frictions of war (i.e., chance and

uncertainty) will affect the outcome of the mission. Clearly the frictions of

war can be detrimental to success, but through good preparation and strong

moral factors, the frictions can be managed. The inherent problem with special

operations that rely entirely on stealth is obvious. If that concealment is

compromised, the mission has little or no chance of success.

Although there were some differences in the individual

profiles, basically all three torpedoes reached the critical points at

approximately the same time. At midnight on 19 December 1941, all three

torpedoes entered the harbor and passed by the antisubmarine net. This was the

point of vulnerability, but because the British did not know the torpedoes were

in the harbor, the Italians began with relative superiority, albeit not very

decisively. As the manned torpedoes continued into the harbor, circumventing the

picketboats and pier security, their probability of mission completion improved

marginally. Their decisive advantage came when they penetrated the antitorpedo

nets. After this point, there were no other defenses that could prevent them

from successfully fulfilling their mission. However, as the graph depicts,

there was still an area of vulnerability even after overcoming the antitorpedo

net. Had the Italians been detected (for instance, when Bianchi floated to the

surface), the British crews could have dropped concussion grenades and possibly

stopped the attack. Fortunately for the Italians, they were able to set their

charges before the British detected them. Three hours later the charges

exploded, and the mission was complete.

The Principles of

Special Operations

Simplicity. This mission had several advantages not normally

associated with a special operation. Although the target was clearly strategic,

with the balance of the naval forces in the Mediterranean hinging on the

mission success, the execution was almost an extension of routine training and

wartime operations. Under Borghese’s command the Scire had previously conducted

three missions that paralleled the attack on Alexandria. Durand de la Penne and

Bianchi were also veterans of a previous attempt to attack the British. This

experience helped mold the approach the Italians took in planning and preparing

for Alexandria.

The lessons of the disaster at Malta convinced Borghese, who

was the overall mission commander, not to create a complex plan of operation.

Borghese limited the objectives by reducing the forces assigned to attack

Alexandria. He could just as easily have incorporated another three manned

torpedoes and several E-boats to overload British defenses and ensure the

Italians of some success. Additionally, although each manned torpedo had only

one warhead, it was possible, and often rehearsed, for each crew to hit

multiple targets by placing the smaller limpet mines on as many ships as

feasible. Borghese chose to avoid both these pitfalls and limit each manned

torpedo to only one target with “all other targets consisting of active war

units to be ignored.” Although not involved in the planning, Bianchi recognized

the need to limit the number of targets. He said later, “In limiting the attack

to one objective [per crew] the commander considered having the offensive power

increased.” Even attacking one target became difficult. In each of the three

cases the frogmen were able to execute their assigned tasks, but only after

overcoming significant physical problems (vomiting, unconsciousness, headaches)

and equipment failures (dry suit leaks, flooded torpedoes). Had the mission

called for more than one target per dive pair, it is unlikely the divers would

have had the physical or technical resources to complete it. Also, with

multiple targets, the fuses on the charges would have to have been set for more

time to allow the divers time to attack their other targets and escape.

Arguably this might have allowed the British to find the charges or move the

vessels from their anchorage (in Durand de la Penne’s case, moving the vessel

would have prevented any damage to the Valiant). In either case, limiting the

objectives clearly simplified the plan and allowed maximum effort to be applied

against the primary targets.

Borghese knew the value of accurate intelligence, and he

consistently used it throughout the operation to reduce the unknown variables

and improve the divers’ chances of success. Knowing the physical limitations of

divers exposed to cold water, Borghese insisted on getting his submarine as

close to the harbor entrance as possible. Italian agents in Alexandria provided

the 10th Light Flotilla with a clear picture of the British defenses and in

particular the minefields off the coast. Borghese wrote later, “I had therefore

decided that as soon as we reached a depth of 400 meters [which was probably

where the minefield started], we would proceed at a depth of not less than 60

meters, since I assumed that the mines, even if they were anti-submarine, would

be located at a higher level.”

This information eventually allowed the Scire to maneuver to

a point only 1.3 miles from the entrance of the harbor. So close, in fact, that

after launching the torpedoes, Durand de la Penne stopped his assault crews for

a sip of cognac and a tin of food.

The torpedo crews were also provided the latest human

intelligence and aerial reconnaissance photos to allow them to plot courses and

find the simplest approach to the target. Borghese noted during the preparation

phase that the divers’ desks “were covered with aerial photographs and

maps … daily examined under a magnifying glass and annotated from the

latest intelligence and air reconnaissance reports; those harbours, with their

moles, obstacles, wharfs, docks, mooring places and defences, were no mysteries

to the pilots, who perfectly knew their configuration, orientation and depths,

so that they, astride the ‘pig’, could make their way about them at night just

as easily as a man in his own room.”

The accurate intelligence had simplified the problem of

negotiating minefields and navigating in an enemy harbor. Alexandria Harbor was

thirty-five hundred miles from Italy. It was ringed with antiaircraft guns and

supported by Spitfires from the Royal Air Force. It seemed impenetrable from

the air. On the other hand, the Italian navy, which had almost no presence in

the eastern Mediterranean, posed no significant threat to the more than two

hundred vessels (merchant and warships) tied up in Alexandria. The only major

fears the British had were from submarines and saboteurs, and extensive

precautions had been taken to overcome both these possibilities. Until the

establishment of the 10th Light Flotilla and the innovations that followed

(i.e., the manned torpedoes, diving rigs, limpet mines, Belloni dry suits, and

submarine transport chambers), the difficulty of penetrating the static

defenses of Alexandria was not worth the risk in human lives or equipment.*

These innovations allowed the Italians to reconsider the possibility of a

direct assault.

The most significant tactical innovation was the use of

disposable torpedoes. Having to plan for only a one-way trip meant enhanced

time on target for the divers and reduced the threat envelope for the submarine

Scire. Obviously one-way trips have their drawbacks for the individual

operators, but from a mission accomplishment standpoint they improve the

possibility of success by reducing the extraction variables. The technological

innovations allowed the divers to completely bypass the British defenses. The

small visual signature of the manned torpedo provided the Italians a host of

tactical advantages. It allowed them to surface unobserved and ride out the

depth charges. They were able to navigate around the harbor undetected by ballasting

the submersible just under the surface. These actions would not have been

possible with either a midget submarine or a conventional submarine. The ease

of handling the torpedo also allowed the crews to climb over antitorpedo nets

and allowed Durand de la Penne to physically move his flooded machine to a

position under the Valiant’s keel. Innovation simplified the assault plan by

eliminating the defensive threats posed by the nets and depth charges, and it

was without question the dominant factor in the success of the mission.

Security. The raid on Alexandria again demonstrates how the

importance of security was not a function of hiding the intent of the mission

but of the timing and the insertion means. By December 1941 British

intelligence was fully aware that the Italians had manned submersibles capable

of penetrating their harbors. The second Italian attack on Gibraltar had

provided the British with one torpedo and its crew. The attack on Malta had

also resulted in the capture of Italian frogmen. And the sinking of the Gondar

resulted in the capture of Elios Toschi, the designer of the original manned

torpedo. With all this information, the British unquestionably knew the kind of

operations they could expect from the 10th Light Flotilla. As Winston Churchill

later said in his speech to the House of Commons, “Extreme precautions had been

taken for some time past against the varieties of human torpedo or one-man

submarines entering our harbours.” Even with all these precautions, however,

the Italians still managed to sneak in and destroy the fleet.

The security employed by the Italians was tight but not

overbearing. It did not prevent Borghese from asking for volunteers from among

all the members of the 10th Light Flotilla, nor did it prevent the crews from

conducting several full-mission profiles in and around La Spezia Harbor,

although in both cases it is believed that the actual target was not made known

to the general participants.

Borghese was, however, cognizant of the need to conceal the

timing of the operation. Upon departing La Spezia for the final voyage, he

ensured that the Scire’s transport chambers were visibly empty, and he did not

load the manned torpedoes until he was out of sight of the harbor. He took

these actions to convince possible onlookers that the Scire was out for just

another routine operation. Borghese kept up pretenses when he arrived in Leros.

While in port he had the transport chambers covered to reduce speculation about

the submarine’s mission, and he refused an admiral’s order to conduct another

exercise for fear of compromising the impending mission.

Borghese also understood that all things being equal,

operational needs were more important than security. Throughout the mission he

maintained radio contact with Athens and Rome. Although interception of the

message traffic could have compromised the mission, Borghese obviously felt the

need for updated intelligence outweighed that concern. In the end, Italian

security was instrumental in preventing the enemy from gaining an advantage by

knowing the timing of the mission. A good special operation will succeed in

spite of the enemy’s attempt to fortify his position, provided security

prevents the enemy from knowing when and how the attack is coming. In the case

of the Italians’ attack on Alexandria, security achieved its aims.

Repetition. The principle of repetition as it applies to the

attack on Alexandria can be viewed in both the macro and the micro senses of

the word. The manned torpedoes of the 10th Light Flotilla had a very limited

role: to conduct attacks on ships in port. Every mission profile was similar:

launch from the submarine, transit to the objective, cut through the nets,

place the charge, and withdraw. Because of this narrowly defined role every

training exercise added to the base of knowledge of the operator regardless of

what specific mission he would eventually undertake. If one considers that each

of the six divers had been on board the 10th Light Flotilla an average of

eighteen months (Durand de la Penne and Bianchi almost two years), during which

time they had dived at least two times a week, then each man had over 150

dives. In addition, three of the divers (Durand de la Penne, Bianchi, and

Marceglia) had previously conducted wartime missions, and all of the divers had

at one time or another been designated as reserve crewmembers and undergone a

complete mission workup. So, in the macro sense, the only aspect of the

Alexandria mission that had not been rehearsed well over one hundred times was

the exact course the divers would take.

The operational and reserve crews for the Alexandria mission

were assembled in September 1941 to begin mission-specific training. It was

during this preparation that the crews conducted exact profiles of the

Alexandria mission. Borghese reported that this training “became highly

intensified, this being the key to secure the greatest possible efficiency in

the men and materials composing the unit. The pilots of the human

torpedoes … travelled to La Spezia twice a week and were there dropped

off from a boat or, in all-around tests, from one of the transport submarines,

and then performed a complete assault exercise, naturally at night; this

consisted of getting near the harbour, negotiating the net-defences, advancing

stealthily within the harbour, approaching the target, attacking the hull,

applying the warhead and, finally, withdrawing.”

Although exact numbers are not available, Spartaco Schergat

indicates that a total of ten full-mission profiles were conducted by all three

crews and the reserves. Other limited dives concentrated on specific aspects of

the mission, such as net cutting or charge emplacement. In the end, however, it

was repetition that provided the divers familiarity with their machines and

their environment. The training became so routine that Schergat later remarked,

“Being in Alexandria or La Spezia was the same. For me it didn’t make any

difference.”

The raid on Alexandria presents a broader view of the

principle of repetition. It shows that repetition must be measured in terms of

both experience and mission-specific training. Special operations forces that

are multidimensional will require more rehearsals and more time during the

preparation phase than a unit whose sole mission encompasses this training on a

daily basis.* However, no amount of experience can obviate the need to conduct

a minimum of two full-dress rehearsals prior to the mission.

Surprise. In an underwater attack, unlike other special

operations, surprise is not only necessary, it is essential. As illustrated in

the relative superiority graph, special operations forces that attack

underwater have the advantage of being relatively superior to the enemy

throughout the engagement as long as they remain concealed. Owing to their

inherent lack of speed and firepower, however, once surprise is compromised,

underwater attackers have little opportunity to escape. Although many

commanders may find this risk unacceptable, experience shows that this type of

operation is mostly successful. During World War II the Italians sank over

260,000 tons of shipping and lost only a dozen men, while the British had

similar successes in both the European and the Japanese theaters. The reason

for this paradox is that it is relatively easy for divers or submersibles to

remain concealed, up to a certain point. Alexandria was a huge harbor with

approximately two hundred vessels anchored out, and wartime conditions called

for all vessels to be at darken ship. Consequently, a small black submersible,

even on the surface of the water, would have been detected only by chance.

However, once the manned torpedoes got within close proximity of the target,

the chance of detection was greatly increased. This is true of all underwater

attacks. The fatigue of the divers, the vigilance of the crew, and the

uncertainty of the situation combine to make the actions at the objective

exceedingly difficult. This is why relative superiority remained only marginal

in this operation until the Italians actually overcame the final obstacle, the

antitorpedo net. Beyond the antitorpedo net the British were least prepared to

defend themselves, and now the Italians had all the advantages.

The antisubmarine and antitorpedo defenses at Alexandria

also show that, contrary to the accepted definition of surprise, the enemy is

usually prepared for an attack. To be effective, special operations forces must

either attack the enemy when he is off guard or, as in the Italians’ case,

elude the enemy entirely. But to assume that the enemy is unprepared to

counterattack is foolhardy and might lead to overconfidence on the part of the

attacker. It is the nature of defensive warfare to be prepared for an attack.

Consequently, if the attacker is compromised, the enemy will be able to react

rapidly and the attacker’s only hope for success lies in quickly achieving his

objective.

Speed. Underwater attacks are rarely characterized by speed.

A quick review of the relative superiority graph shows that it took the manned

torpedoes over two hours from the point of vulnerability until they reached the

antitorpedo net. Throughout this time they were subject to the frictions of

war, and by moving slowly and methodically they only increased their area of

vulnerability. However, as long as the will of the enemy is not infringing on

the relative superiority of the attacker, speed is not essential, although it

is still desirable. Speed becomes essential when the attacker begins to lose

relative superiority. Two of the torpedo crews reached their objectives and

calmly proceeded to attach the explosives and depart. Durand de la Penne,

however, reached his target and immediately began to have difficulties: his

torpedo sank to the bottom, he lost his second diver, his dry suit filled with

cold water, and he was fatigued to the point of exhaustion. As he said in his

after-action report, at that point speed was essential. Durand de la Penne was

rapidly losing his advantage and knew that if he didn’t act quickly “the

operation … would be doomed to failure.”50 The closer an attacker

gets to the objective, the greater the risk. Consequently, speed is still

important to minimize the attacker’s vulnerability and improve the probability

of mission completion.

Purpose. Commander Borghese, who was in overall charge of

the attack on Alexandria, ensured that the purpose of the mission was well

defined and that the divers were personally committed to achieving their

objectives. This was a straightforward mission without any complicated command

and control issues; therefore, defining the goals and objectives—the purpose—was

relatively easy. Each manned torpedo had only one warhead and one target.

Therefore it was essential not to waste the warhead and the effort on an

undesirable objective. Borghese ordered Martellotta and Marino to attack the

aircraft carrier Eagle if she were in port, and if not, the tanker Sagona. Once

inside the harbor, however, the pair accidently attacked a cruiser.

Fortunately, before they could detach the warhead, they realized it was not

their target, and as Borghese notes, “with great reluctance, in obedience to

orders received, abandoned the attack.” Their orders were clear; they

understood the purpose of the mission. They were not to waste their effort on a

small cruiser, but instead were to seek out a larger target, which they

eventually found and destroyed.

Men who volunteered for the 10th Light Flotilla were typical

of special forces personnel everywhere. Each was a combination of adventurer

and patriot. They understood the risks involved in penetrating the enemy’s

harbor and fully accepted the consequences. They did so out of a love for

excitement and the understanding that their missions were important to the

country. Teseo Tesei, who, at Malta, detonated his torpedo underneath himself

in order to achieve his objective, said, “Whether we sink any ships or not

doesn’t matter much; what does matter is that we should be able to blow up with

our craft under the very noses of the enemy: we should thus have shown our sons

and Italy’s future generations at the price of what sacrifice we live up to our

ideals and how success is to be achieved.”

Although Tesei, who had died three months earlier, did not

participate in the Alexandria attack, his inspiration was apparent in the

attitudes of the Alexandria crews. All six divers knew they would be either

captured or killed, and yet Borghese says the difficulties and dangers merely

“increased their determination.” This personal commitment to see the mission

completed at any cost is, as Tesei said, how success is achieved.