From the beginning, Sturdee’s intention to fight at a range

beyond the reach of Spee’s guns had been frustrated by the Germans’ having the

lee position. The dense smoke from the battle cruisers’ funnels was blowing

toward the enemy, obscuring the British gun layers’ view of their targets. In

addition, the discrepancy between the range of the British 12-inch and the

German 8.2-inch guns was only about 3,000 yards, a narrow margin for Sturdee to

find and maintain. For a few moments when the range dropped below 12,000 yards,

the Germans fired rapidly and effectively. Then, at two o’clock, to ensure that

a lucky German shot did not cripple one of his battle cruisers, Sturdee edged

his ships away to port and opened the range to 16,000 yards, where Spee could

not reach him. At the same time, he reduced speed to 22 knots to lessen the

effects of funnel smoke. For the next fifteen minutes, there was a lull in the

action and the two squadrons gradually drew apart.

In this first phase, despite the disparity in strength, the

battle had been far from one-sided. In contrast to the rapidity and accuracy of

German fire, British gunnery had been an embarrassment. During the first thirty

minutes of action, the two battle cruisers fired a total of 210 rounds of

12-inch ammunition. Inflexible had scored three hits on Gneisenau, one below

the waterline and another temporarily putting an 8.2-inch gun out of action,

while Invincible could claim only one probable hit on Scharnhorst. At this rate

the battle cruisers would empty their magazines without sinking the enemy. The

primary cause of this bad shooting was smoke. The wind blowing from the

northwest carried dense funnel smoke and clouds of cordite gas belching from

the gun muzzles down toward the enemy, almost completely blinding Invincible’s

gunners in the midships and stern turrets. The only clear views were those over

the bow from A turret and that of the gunnery officer high in the foretop.

Inflexible’s situation was even worse: she was smothered and blinded not only

by her own smoke but also by Invincible’s smoke blowing across her line of

vision. This excuse notwithstanding, the performance of the battle cruisers

caused deep misgivings. “It is certainly damned bad shooting,” a friend said to

Lieutenant Harold Hickling of Glasgow. “We were all dismayed at the battle

cruisers’ gunnery, the large spread, the slow and ragged fire,” Hickling added

later. “An occasional shot would fall close to the target while others would be

far short or over.” An officer in Invincible’s P turret was alarmed to observe

that “we did not seem to be hitting the Scharnhorst at all.” Said Hickling, “At

this rate, it looks as if Sturdee, not von Spee, is going to be sunk.”

Excessive smoke was not the only cause of the slow,

inaccurate gunfire of the battle cruisers. A British officer in the spotting

top of Invincible, Lieutenant Commander Hubert Dannreuther, who happened to be

a godson of the composer Richard Wagner, found that his excellent, German-made

stereoscopic rangefinder was rendered useless not only by smoke, but also by the

vibration caused by the ship’s high speed, and by the violent shaking of the

mast whenever A turret fired. In Invincible’s P turret, conditions were

impossible. The gun layers could see nothing except enemy gun flashes through

enveloping clouds of smoke, and every time Q turret, across the deck, fired

over them, everyone in P turret was deafened and dazed by the blast. On

Inflexible, Lieutenant Commander Rudolf Verner in the battle cruiser’s foretop

was almost the only man aboard his ship who could judge the location of the

enemy, and he, handicapped by the smoke from the flagship ahead, had great

difficulty observing what damage his gunners were causing.

From afar, however, the battle appeared as a dramatic

tableau. “With the sun still shining on them, the German ships looked as if

they had been painted for the occasion,” said an officer on Kent, coming up

astern. “I have never seen heavy guns fired with such rapidity and yet such

control. Flash after flash traveled down their sides from head to stern, all their

5.9-inch and 8.2-inch guns firing every salvo. Of the British battle cruisers,

less could be seen as their smoke drifted across their range. Their shells were

hitting the German ships. . . . Four or five times, the white puff of a

bursting shell could be seen on Gneisenau. . . . By some trick of the wind, the

sounds were inaudible and the view was of silent combat, the two lines of ships

steaming away to the east.”

In fact, the few large British shells that managed to hit

were inflicting serious damage. “A shell grazed the third funnel and exploded

on the upper deck above . . . ,” said Gneisenau’s Commander Pochhammer. “Large

pieces of shrapnel ripped down and reached the coal bunkers, killing a stoker.

A deck officer had both his forearms torn off. A second shell exploded on the

main deck, destroying the ship’s boats. Fragments smashed into the officers’

mess and wounded the officers’ little pet black pig. Another hit aft entered

the ship on the waterline, pierced the armored deck and lodged in an ammunition

chamber . . . [which] was flooded to prevent further damage. . . . These three

hits killed or wounded fifty men.”

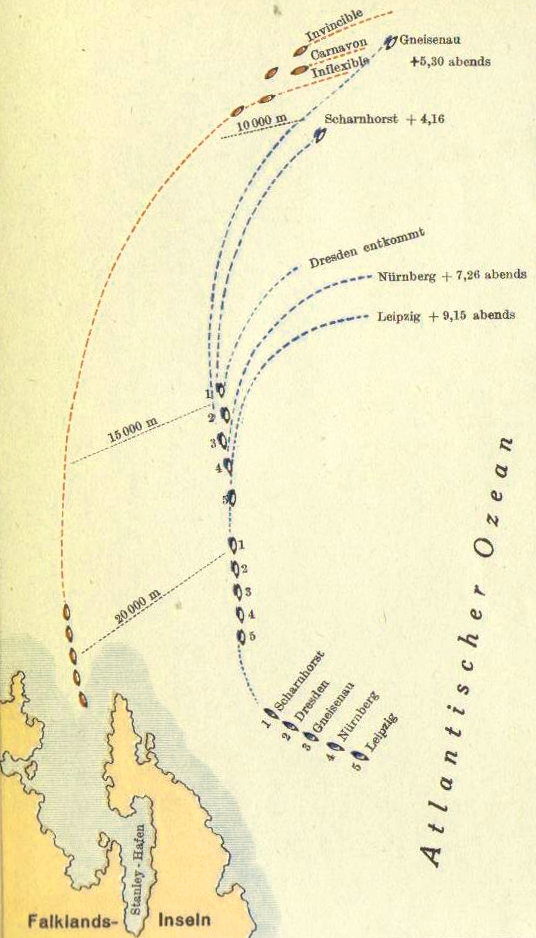

Suddenly, Spee made another move: he turned and made off to

the south, hoping that the pall of smoke over the British ships would obscure

his flight and that in that direction he might find a cloud bank, a rain

squall, a bank of fog. Said Pochhammer: “Every minute we gained before

nightfall might decide our fate. The engines were still intact and were doing

their best.” Because of the smoke surrounding their ship, it took a few minutes

for Invincible’s officers to realize what was happening; by then, Spee had

opened the distance to 17,000 yards. Once Sturdee understood, he swung his

battle cruisers around and chased at 24 knots. He still had sufficient time and

the afternoon remained bright. This second pursuit lasted forty minutes, during

which the range was reduced to 15,000 yards; then the battle cruisers turned to

port to free their broadsides. At 2:45 p.m., the British battle cruisers recommenced

the cannonade.

Eight minutes after Sturdee opened fire, Spee abandoned his

southerly flight, and for the second time took his two armored cruisers around

to the east to accept battle. The German ships turned in unison and once again

broadside salvos of 12-inch and 8.2-inch shells thundered from the opposing

lines. Spee now was trying to come closer. The British were within range of his

8.2-inch guns, but he was maneuvering to close to 10,000 yards, where his

secondary armament of 5.9-inch guns could come into play. Gradually, the two

lines drew nearer; by 3:00 p.m., the range had diminished to just over 10,000

yards and, at extreme elevation, the port German 5.9-inch batteries opened

fire. Invincible suffered more heavily as German gunners concentrated on her;

for the next fifteen minutes, Sturdee’s flagship was hit repeatedly by both

8.2-inch and 5.9-inch shells. One 8.2-inch shell plunged through two decks and

burst in the sick bay, which was empty. Somehow, on the British ships, this

kind of luck seemed to hold; the ship was pummeled, but there were almost no

casualties. When the canteen was wrecked, crew members cheerfully gathered up

the cigarettes, cigars, chocolate, and tins of pineapple scattered across the

deck. Not all the German shells exploded. One 8.2-inch shell cut the muzzle of

a forward 4-inch gun, descended two decks, and came to rest unexploded in the

admiral’s storeroom, nestling between his jams and a Gorgonzola cheese. An

unexploded 5.9-inch shell passed through the chaplain’s quarters, entered the

paymaster’s cabin, where it tumbled dozens of gold sovereigns from his money

chest over the deck, and then passed harmlessly out the ship’s side.

The action was now at its most intense. The fire of the

battle cruisers had become more accurate and both Scharnhorst and Gneisenau

were blanketed by huge waterspouts. Now German spotters, like the British, were

greatly hampered and could not see whether they were hitting. “The thick clouds

of smoke from the British funnels and guns obscured our targets so that, apart

from masts, only the sterns were visible,” said Pochhammer. “Again we tried to

shorten the distance but this time the enemy was careful not to let us approach

and we knew that we were in for a battle of extermination.” Time after time,

Scharnhorst shuddered as 12-inch shells pierced her deck armor and exploded in

her mess decks and casements. One 12-inch shell hit a 5.9-inch gun, exploded,

and tumbled gun and gun crew into the sea. Gneisenau was also suffering. A huge

explosion smashed the starboard engine room; water flooded in and, when the

pumps became unworkable, the compartment was abandoned. Splashes from 12-inch

shells landing in the sea nearby were throwing huge volumes of water over the

decks, sometimes extinguishing fires set by previous, more accurate shells.

By 3:15 p.m., the action had been under way for two and a

quarter hours. From the spotting tops, the scene remained the same: a cloudless

sky, a calm surface ruffled by a breeze, and, from the two groups of ships,

clouds of black smoke punctured by the orange flashes of guns. On Invincible’s

bridge, Sturdee sensed that time was passing, the afternoon waning, the matter

dragging out. The smoke interference plaguing his gun layers was now so

intolerable that the admiral led his battle cruisers around to port, back

across their own wakes, navigating an arc from which they emerged at 3:30 p.m.

on a southwesterly course with Inflexible leading. This placed the battle

cruisers on the windward side of the German ships and for the first time they

had a clear view of their targets. With Inflexible now in front, Verner was at

last able to observe the enemy and the effects of his own ship’s gunnery. By

3:35 p.m., he said, “for the first time I experienced the luxury of complete immunity

from every form of interference. . . . I was now in a position to enjoy the

control officer’s paradise: a good target, no alterations of course, and no

‘next-aheads’ or own smoke to worry one.” During the turn, two of Scharnhorst’s

8.2-inch shells struck Invincible’s stern, wrecking the electric store and the

paint shop, and a 5.9-inch shell exploded on the front plate of A turret

between the two guns, which dented, but did not pierce, the armor. These hits

on the British battle cruisers did nothing to reduce their fighting value.

Spee countered Sturdee’s turn by suddenly turning again

himself, this time back to starboard, heading northwest as if to parry Sturdee

by crossing his bows. In fact, Spee’s reason for swinging his ships was that so

many guns on the Scharnhorst’s port side were out of action that he wished to

bring his other broadside to bear. And, indeed, once the turn freed her

disengaged side, the fresh starboard batteries opened a brisk fire. Gneisenau,

not nearly so badly damaged and still firing all of her 8.2-inch guns, followed

the flagship around and engaged Invincible. British shells crashed into the sea

near the German ship and drove torrents of seawater across the ruins of her

upper deck. Fire parties found themselves struggling to keep their feet in this

surging flood. Worse, a hit on Gneisenau below the waterline flooded two boiler

rooms, reducing her speed to 16 knots and giving her a list to port that made

her port 5.9-inch guns unusable.

At this moment, when the two squadrons were trading blow for

blow, an apparition appeared four miles to the east. A white-hulled,

full-rigged, three-masted sailing ship, flying the Norwegian flag and bound for

the Horn with all canvas spread, was, in the words of a British officer, “a

truly lovely sight . . . as she ran free in the light breeze, for all the world

like a herald of peace.”

Scharnhorst, still plunging ahead through a forest of

waterspouts, now had been struck by at least forty heavy shells. And there was

no respite; with implacable regularity, orange flames glowed from Invincible’s

turrets and a few minutes later more 850-pound shells burst on Scharnhorst’s

deck or plunged through to the compartments below. What surprised the British

was the volume of fire still coming back from a ship as badly battered as

Scharnhorst. Her upper works were a jungle of torn and twisted steel; her masts

and her third funnel were gone and the first and second funnels were leaning

against each other; her bridge and her boats were wrecked; clouds of white steam

billowed up from the decks; an enormous rent was torn in her side plating near

the stern; red and orange flames could be seen in her interior; and she was

down three feet at the waterline. Yet still her battle ensign fluttered from a

jury mast above the after control station and still her starboard batteries

fired. From Invincible’s spotting top, Dannreuther reported, “She was being

torn apart and was blazing and it seemed impossible that anyone could still be

alive.” On Inflexible, Verner, astounded by the continuing salvos from the

German armored cruisers, ordered his crews to fire “rapid independent,” with

the result that at one point, P turret had three shells in the air at the same

time, all of which were seen to land on or near the target. Yet the German fire

continued. “We were most obviously hitting [Scharnhorst,] but I could not stop

her firing. . . . I remember asking my rate operator, ‘What the devil can we

do?’ ”

At about this time, a shell splinter cut the halyard of

Spee’s personal flag on Scharnhorst and Captain Maerker on Gneisenau noticed

that the admiral’s flag no longer flew from the flagship’s peak. If Spee was

dead, Maerker would be in command of the squadron. He signaled: “Why is the

admiral’s flag at half mast? Is the admiral dead?”

Spee replied, “No, I am all right so far. Have you hit

anything?”

“The smoke prevents all observation,” Maerker said.

Spee’s last signal was characteristically generous and

fatalistic. “You were right after all,” he said to Maerker, who had opposed the

attack on the Falklands.

Nevertheless, for another half hour, Scharnhorst’s starboard

batteries boomed out. Then, just before four o’clock, she stopped firing.

Sturdee signaled her to surrender, but there was no reply. Instead, slowly and

painfully, the German cruiser’s bows came around. Listing to port, with three

of her four funnels and both her masts shot away, her bow so low that waves

were washing over the forecastle, Scharnhorst staggered across the water toward

her enemy. As she did so, Spee sent his last signal to Gneisenau: “Endeavor to

escape if your engines are still intact.” At just that moment, Carnarvon

arrived on the scene and opened fire with her 7.5-inch and 6-inch guns. These

blows were gratuitous. With water pouring into her bow, Scharnhorst rolled over

on her side. Then, at 4:17 p.m., her flag still flying, her propellers turning

in the air, the armored cruiser went down, leaving behind a cloud of steam and

smoke. Every one of the 800 men on board, including Admiral von Spee, went down

with her. Sturdee’s battle cruisers, still under fire from Gneisenau, did not

stop to look for survivors, and fifteen minutes later, when Carnarvon passed

over the spot, her crew saw nothing in the water except wreckage.

Once her sister was gone, Gneisenau was subjected to an hour

and a half of target practice by the two British battle cruisers. Salvos of

12-inch and smaller shells smashed into the ship, shattering her funnels,

masts, and superstructure and flooding a boiler room and an engine room. The

Germans still fired back, aiming mainly at Invincible and hitting the British

flagship three times in fifteen minutes. One of these hits struck and bent the

armored belt at the waterline; the result was the flooding of one of the battle

cruiser’s compartments. But this success could not reverse the conclusion. The

British ships, steaming in a single ragged line, were firing at a range of

10,000 yards, but so dense was the smoke that they still had difficulty in

observing their own gunfire. At 4:45 p.m., no longer able to contain his

frustration, Inflexible’s Phillimore abruptly turned out of line, reversed

himself to port, and ran through the smoke clouds out into the sunlight.

Gneisenau lay 11,000 yards away on his starboard beam. Now with a clear and

slow-moving target at relatively close range, Inflexible opened a devastating

fire. Phillimore had no order from Sturdee to make this turn, but the admiral

understood and later approved. Nevertheless, a few minutes later, Sturdee

ordered reforming of the original battle line with his flagship leading. Much

to Verner’s disgust, he found himself once again blinded by Invincible’s smoke.

For the Germans, there was no chance of escape; Maerker

faced a choice between surrender and annihilation. He made his choice and held

his ship on a convergence course with Invincible, ordering stokers from the

wrecked boiler and engine rooms to fill out the ammunition parties feeding the

starboard batteries. Even at the end, according to the gunnery officer, “the

men with their powder-blackened faces and arms, [were] calmly doing their duty

in a cloud of smoke that grew ever denser as the firing continued; the rattling

of the guns running backwards and forwards; the cries of encouragement from the

officers, the monotonous sound of the order transmitters, and the tinkle of the

salvo bells. Unrecognizable corpses were thrust aside; on the walls were

splashes of blood and brains.” Below, seawater was pouring into an engine room,

a boiler room, and a dynamo room and over the sucking and swirling sounds of

water came the cries of trapped and drowning men. Dense clouds of smoke and

steam swirled through total darkness. As the dead and wounded grew in number,

the size of the ammunition parties dwindled. The wireless station was destroyed

and the wireless officer’s head blown off. In the medical dressing station, the

ship’s doctor and the ship’s chaplain were killed.

It was time to end it. Sturdee brought his ships in and

pounded Gneisenau from 4,000 yards. The vessel was a place of carnage. Her

bridge and foremast were shot away, her upper deck a mass of twisted steel,

half her crew dead or wounded. One of Carnarvon’s shots had buckled Gneisenau’s

armored deck, jamming it against the steering gear and forcing the ship into a

slow, involuntary turn to starboard. Yet despite this devastation, the armored

cruiser’s port guns and fore turret continued to fire spasmodically. At 4:47

p.m., she ceased firing and no colors were seen, but it was uncertain whether

she had struck—several times her colors had been shot away, and each time they

had been hoisted again. At 5:08 p.m., her forward funnel crashed over the side.

By 5:15 p.m., Gneisenau had been silent long enough for Sturdee to order “Cease

Fire,” but before the signal could be hoisted, a jammed ammunition hoist on

Gneisenau came free, shells again reached the cruiser’s fore turret, and a

final, solitary shot was fired at Invincible. Grimly, the battle cruisers

returned to work. A last British salvo was fired and she halted, rocking in the

swell, water flooding in through the lower starboard gun ports. At 5:50,

Sturdee repeated his signal to “Cease Fire.” Still, the German cruiser’s flag

remained flying.

At 5:40 p.m., Maerker had given orders to scuttle the ship.

The stern torpedoes were fired and the submerged tubes left open to the sea

while explosive charges were fired in the main and starboard engine rooms. With

thick smoke clinging to her decks and water gurgling and gushing through the

hull, the ship rolled slowly over onto her starboard side. Gneisenau went down

differently from Scharnhorst, submerging so slowly that men on deck were able

to muster and climb down the ship’s sides as she heeled over. Survivors

estimated that about 300 men were still alive at that time. Emerging on deck,

the men, coal blackened from the bunkers and the engine rooms, carried the

wounded with them and began putting on life belts. As the ship slowly heeled

over, Captain Maerker ordered three cheers for the kaiser and there was a thin

chorus of “Deutschland, Deutschland über alles.” When the order “All men

overboard” came, the men slid down the side and jumped into the water. At 6:00

p.m., Gneisenau sank and British seamen, watching from Inflexible, began to

cheer until the captain ordered silence and commanded his men to stand at

silent attention as their enemy went down.

When their ship went down, between 200 and 300 survivors

were left struggling in the water. A misty, drizzling rain was falling, the sea

was beginning to roughen, there was a biting wind, and the temperature of the

water was 39 degrees Fahrenheit. The British battle cruisers, 4,000 yards away,

carefully closed in on the survivors, attempting to repair and launch their own

damaged boats, steaming slowly, lowering boats, and throwing ropes. All around

the ships, rising and falling on the swell, men floated, some on hammocks, some

on spars, some dead, some still alive and struggling, then drowning before a

boat could reach them. A few German sailors were able by their own efforts to

swim to the high steel sides of a British ship and be pulled in by ropes. Some

were so numbed by the shock of cold water that they could not hold on to

anything and drowned within sight of the rescuing boats and ships. Some were

alive but too weak and, before they could be brought in, drifted helplessly

away into the dark. The wind brought awful cries from the men in the water. “We

cast overboard every rope end we had . . . ,” said a young English midshipman,

“trying to throw to some poor wretch feebly struggling within a few yards of the

ship’s side. If we missed him, the swell would carry him out of reach. We could

do nothing but try for another man. . . . Some of the Germans floated away,

calling for help. It was shocking to see the look on their faces as they

drifted away and we could do nothing to save them.” Every effort was made; when

Carnarvon with Stoddart on board reacted slowly in joining the rescue work,

Sturdee dropped his mask of imperturbability. “Lower all your boats at once,”

he signaled imperatively, and Carnarvon lowered three boats, which picked up

twenty Germans. By 7:30 p.m., the rescue work was completed. Of Gneisenau’s

complement of 850 men, Invincible had brought aboard 108, fourteen of whom were

found to be dead after being lifted on deck. Inflexible picked up sixty-two,

and Carnarvon twenty. Heinrich von Spee, the admiral’s son, did not survive.

One of those saved was Commander Pochhammer, second in

command of Gneisenau. After the war, he recalled:

The ship inclined more

and more. I had to hold tight to the wall of the bridge to avoid sliding . . .

then Gneisenau pitched violently and the process of capsizing began. . . . I

felt the ship giving way under me. I heard the roaring and surging of the water

come nearer. . . . The sea invaded a corner of the bridge and caught me. . . .

I was caught in a whirlpool and dragged into an abyss. The water eddied and

murmured around me and droned in my ears. . . . I opened my eyes and noticed it

was brighter. . . . I came to the surface. The sea was heaving. . . . I saw . .

. [our ship] a hundred yards away, her keel in the air[;] the red paint on her

bottom glistened in the sunset. In the water around me were men who gradually

formed large and small groups. . . . Albatrosses with three to four yards

wingspan surveyed the field of the dead and avidly sought prey. . . . It was a

consoling though mournful sight to see the first of the English ships

approaching . . . to see her brought to a standstill as near to us as appeared

possible, her silent crew ranged along the side, throwing spars to help support

us and making ready to launch boats. One boat was put in the water, then

re-hoisted because obviously it was damaged and leaked. . . . The wind and the

swell were slowly driving the English away from us. Eventually, two boats were

launched . . . a smaller one . . . [came] in our direction, a sort of dinghy,

four men were rowing . . . a young midshipman in the bow. A long life line was

thrown to me . . . [but] I lacked strength to climb into the boat. The boat was

half full of water. Eventually, the little boat bobbed alongside the giant,

whose flanks had a dirty, yellow color. . . . I was quite unable to climb the

rope ladder offered to me. A slip knot was passed under my arms . . . and then,

all dripping, I found myself on a ship of His Britannic Majesty. From the hat

bands I saw it was the Inflexible.

Wrapped in blankets, given a hot-water bottle and brandy,

and placed in a bunk in the admiral’s quarters, Pochhammer was treated as a

guest of honor. Even in the cabin, the German officer was cold; British

warships, he discovered, were not heated by steam but by small electric stoves.

Captain Phillimore came to see him and invited him to dinner in the officers’

wardroom. There, Pochhammer, who spoke English, was offered ham, eggs, sherry, and

port. Gradually, other rescued German officers appeared. That evening, as the

senior surviving officer of the East Asia Squadron, he was handed a message

from Admiral Sturdee: “Flag to Inflexible. Please convey to Commander of

Gneisenau: The Commander-in-Chief is very gratified that your life has been

spared and we all feel that the Gneisenau fought in a most plucky manner to the

end. We much admire the good gunnery of both ships. We sympathize with you in

the loss of your admiral and so many officers and men. Unfortunately the two

countries are at war. The officers of both navies who can count friends in the

other have to carry out their country’s duty, which your admiral, captain and

officers worthily maintained to the end.” Commander Pochhammer replied to

Sturdee: “In the name of all our officers and men I thank Your Excellency very

much for your kind words. We regret, as you, the course of the fight as we have

learned to know during peacetime the English Navy and her officers. We are all

most thankful for our good reception.” That night, falling asleep, Pochhammer

felt the vibrations as Inflexible moved at high speed through the South

Atlantic.

The pursuit of the German light cruisers continued through

the afternoon into darkness. For over two hours, from 1:25 p.m. to 3:45 p.m.,

in a straightforward stern chase, Glasgow, Kent, and Cornwall raced south after

Leipzig, Dresden, and Nürnberg. The pursuing British ships—two armored cruisers

and a light cruiser—were overwhelmingly superior in armament: Kent and Cornwall

each carried fourteen 6-inch guns and Glasgow had two 6-inch and ten 4-inch; if

the British could catch the Germans, the outcome was certain. In this

situation, however, success depended more on speed than on guns and, except in

the case of Glasgow, the margin of speed was narrow.

When the three German light cruisers broke away to the

south, they were ten to twelve miles ahead of their pursuers. Had their design

speed still been applicable—Nürnberg’s and Dresden’s were over 24 knots,

Leipzig’s 23—their chance of escape would have been excellent. Nominally,

Glasgow, designed to reach 26½ knots, could catch them, but one ship could not

possibly have overtaken and overwhelmed three. Here, however, design speeds did

not apply. The German ships had been at sea for four months with no opportunity

to clean their hulls, boilers, and condensers. Beyond decreased efficiency and

slower speeds, any attempt to force these propulsion systems to generate

sustained high speeds could actually pose a threat. Under the extreme pressures

reached in a high-speed run, boilers and condenser tubes contaminated by the

processing of millions of gallons of salt water might leak, rupture, even

explode.

Glasgow quickly developed 27 knots and drew ahead of

Cornwall and Kent. By 2:45 p.m., Luce, who was the senior officer on the three

British cruisers, found himself nearly four miles ahead of his own two armored

cruisers and within 12,000 yards of Leipzig. He opened fire with his bow 6-inch

gun. One shell hit Leipzig, provoking her to turn sharply to port to reply with

a 4.1-inch broadside. The first German salvo straddled Glasgow and when the

next salvo scored two hits, Luce pulled back out of range. This reciprocal

maneuver was repeated several times, but each time Leipzig turned to fire, she

lost ground, giving the two slower British armored cruisers opportunity to

creep up.

At 3:45 p.m., the German light cruiser force divided.

Dresden, in the lead, turned to the southwest, Nürnberg turned east, and

Leipzig continued south. Luce had to make a choice. For over an hour, his

Glasgow, in front of Kent and Cornwall, had been firing at Leipzig, the

rearmost of the German ships. The leading German ship, Dresden, already had a

start on him of sixteen miles. The sky was clouding over; rain squalls were in

the offing; at the earliest, if he pursued the distant Dresden, Luce could not

come up within range until 5:30 p.m. He therefore decided to make sure of the

two nearer, slower German ships and to let Dresden go. As the sky became

overcast, then turned to mist and drizzle, Dresden grew fainter in the distance

and eventually faded from sight.