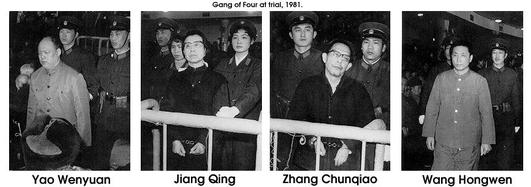

The Gang of Four at their trial in 1981

The collapse of the Guomindang regime and Jiang’s flight to

Taiwan did not end China’s civil war. Mao proclaimed the People’s Republic

(PRC) in Beijing, but Jiang still insisted that his regime was the legitimate

government of the Republic of China (ROC). Both sides refused to view Taiwan as

a separate state. To the PRC, Taiwan is simply a rebellious province, over

which it claims sovereignty. To the ROC, the entire mainland consisted of

rebellious provinces.

American policy might have favoured a partition of China, as

had happened in Germany and Korea. But this was as repellent to Jiang as it was

to Mao. Jiang appears genuinely to have believed that Mao’s regime would prove

too incompetent and brutal to survive long. The chaos of the Great Leap Forward

in 1958 and the Cultural Revolution from 1966 suggest that this view was not entirely

fantasy. But more realistically there was always the hope that the USA might

defeat the PRC and reinstall his regime. To Mao, who was far more of a

nationalist than most Americans realised, the existence of a separate regime in

Taiwan was intolerable. There also was the danger that America would indeed

attack the PRC from Taiwan. He wanted to invade the island and complete the

reunification of China.

The situation was therefore unstable. Other powers were

required to choose which to recognise as the legitimate government. Also, given

the danger of renewed fighting, how deeply committed dare the USSR and USA

become to either side? Britain had always been pragmatic on such questions: the

Communists ruled China and were therefore the government. Britain’s only

interest was Hong Kong, and the PRC found the status quo there useful. Britain

recognised the PRC almost immediately. America could not do this. Americans had

long held unrealistic views on China, and Truman was widely criticised for `losing’

China. Also, at American insistence, China had been awarded a permanent seat on

the UN Security Council. They had no wish to see the PRC inheriting that seat.

They continued to recognise the ROC, but hesitated to enter into security

commitments that might allow Jiang to drag them into a war in China.

US attitudes changed through the Korean War. Still certain

that the Communist world was monolithic; they saw this as part of a global

Soviet strategy. The USA decided that their interests would not allow a

Communist take-over of Taiwan. It might lead to Communist domination of the

western Pacific, and ultimately the entire ocean. Other states, fearing being

drawn into a major war, declined to extend collective security to Taiwan via

SEATO (Southeast Asia Treaty Organisation). America therefore reached a

bilateral security agreement with Jiang in December 1954.

This was a risky step. Mao had planned to invade Taiwan, but

his resources had been diverted to Korea. With that war over he could return to

Taiwan. The immediate issue was that the Guomindang had clung on to a number of

islands off the mainland. They included the Taschen Islands, Matsu and Quemoy –

the latter being less than three kilometres from the mainland. They had no

military value, but Jiang refused to abandon them. Mao was deeply offended at

the PRC’s exclusion from the Security Council and the Taiwan-USA security

negotiations. He ordered the shelling of Quemoy in March 1954, which suddenly

became a massive barrage in September.

Eisenhower realised these islands were worthless but was in

a quandary. He did not wish to go to war, but the ROC lobby was clamouring for

strong action. Also the loss of these islands would reflect badly on the USA as

Taiwan’s supporter, which might undermine America’s other alliances. It might

suggest that America could not stop the advance of Communism in Asia.

Eisenhower’s European allies, however, had no intention of fighting a war over

such a trivial issue. He still hurriedly concluded the security agreement with Taiwan

and hinted that America was prepared to use tactical nuclear weapons to defend

the islands. The PRC scoffed at these steps, but along with Soviet pressure to

avoid escalating tensions they had their effect. The shelling died down. But

not before the PRC stormed Yijiangshan Island. This convinced America that the

Taschens were untenable and they forced Jiang to evacuate them.

After this, for America to allow the loss of Matsu and

Quemoy would be too great a humiliation. Also, as Jiang had crammed them with

his best troops, their loss could lead to the loss of Taiwan. When Mao renewed

the shelling in 1958, Eisenhower felt he had no choice but to offer US support.

His renewed talk of tactical nuclear weapons shocked his allies. Again tensions

died down. Jiang was required to make a statement repudiating the use of force

in regaining the mainland. Mao responded by shelling Quemoy only on alternate

days. This gave the crisis a surreal quality, and one difficult to take too

seriously.

As a result of these crises America had made a comprehensive

commitment to Taiwan. America was angered at European hesitancy over Taiwan.

But the PRC was also deeply angered at the timidity of the USSR, who found the

islands a ludicrous issue over which to risk war. This would put far greater

strains on Soviet alliances than on American.

The Cultural

Revolution

In September 1949 Mao Zedong proclaimed the People’s

Republic of China (PRC). He had united China, restored effective central

government and freed it from foreign domination. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP)

he led was effective and feared, but also generally respected. His personal

stature was massive. He towered over his associates and had a `cult of

personality’, presenting him as a demigod. But he was not necessarily satisfied.

He had not won power for its own sake, but to fundamentally transform China. He

felt he had cause to worry that he was failing in this.

Feeling his regime secure, in 1957 he launched the `hundred

flowers’ movement: promising immunity to those offering constructive criticism

of his state. Instead of the minor complaints he expected, intellectuals

actually questioned the very foundations of Communism. Shocked at the scale of

opposition, Mao concluded his revolution was not secure after all. He lashed out

viciously at the critics. But worse was to follow. With the PRC’s friendship

with the USSR breaking down, Mao decided that China must race towards

socialism, industrialisation and modernisation, lest his revolution fail. In

1958 he launched the `Great Leap Forward’. The idea was instant modernisation

via mass mobilisation. Agricultural collectivisation was completed and peasant

communes ordered to produce vast quantities of steel in homemade furnaces. The

result was catastrophic. Millions died in the resulting famine. The prestige of

the CCP was badly undermined.

Mao could not accept the failure was due to his entire

approach being an unrealistic fantasy. The fault, he concluded, was in the CCP

and its failure to really change China. The CCP must have lost contact with the

proletariat and peasantry. Far too many recruits had been permitted to join the

CCP without repudiating fully their bourgeois attitudes. They had sought the

privileges of rank, become authoritarian and felt themselves superior. In fact,

Mao believed the CCP was in danger of the same failings he perceived in the

Soviet Communist Party. It was ceasing to be revolutionary. His achievements

would be quietly eroded after his death.

The only solution Mao could see was to launch a new

revolution. This revolution would not be led by the Party, but be directed

against the bourgeois elements within it and within the government system.

Feeling that the young were truly revolutionary, he aimed to mobilise them to

this end. The first rallying call to a new revolution came in June 1966, when

posters appeared criticising academics at Beijing University. Students, and

soon schoolchildren, were urged to defy authority. The Red Guards soon emerged

to be the vanguard of Mao’s new revolution. They were urged to denounce

academics, writers, indeed any in the arts, who might be peddling bourgeois

ideas. Denunciation soon turned to punishment. Some of China’s most renowned

figures were humiliated, imprisoned, tortured and even murdered. When

authorities attempted to restore discipline, they were themselves denounced as

counterrevolutionary.

The CCP attempted to defend itself by taking control of the

movement. The Red Guards soon became split into hostile factions:

`conservatives’, often children of Party members and those with a stake in the

existing order, and `radicals’, generally of unprivileged backgrounds. Both

claimed to be pursuing the Cultural Revolution in the name of Mao. An element

of civil war was introduced into the crisis. By August 1967 the factions were

fighting pitched battles in many areas. Mao clearly wanted the radicals to

seize power and put his revolution back on course. But given their youth, they

were hardly suited for such a role. Also the growing chaos was alienating the

Chinese people. There was a danger that the PRC would collapse.

With the Party and the state paralysed, the only institute

able to supply any stability was the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). Troops had

to be deployed to protect essential services and industries from destruction.

Mao wanted them to support the radicals. But generally PLA commanders were

hostile to the radicals, often arming and supporting conservatives. Clashes

between the PLA and radical Red Guards spread across China. The violence in

Sichuan was especially severe, but in many places civil strife left hundreds of

thousands dead and injured. Having done so much damage, however, Mao could not

afford to turn the Red Guards loose against the PLA. From September 1967 the

PLA gradually restored a semblance of order in the PRC, for example, disarming

fighting factions in Guangxi and Shanxi. Millions of Red Guards, their

educations curtailed and lacking any skills, were dispatched to the countryside

to be labourers. This did not end the Cultural Revolution. A witch-hunt for

class enemies was launched reminiscent of Stalin’s purges. Though without the

earlier mayhem, it destroyed millions of lives through denunciation, forced

confessions and brutal punishment.

The Cultural Revolution only really ended with the defeat of

the `Gang of Four’ in the power struggle following Mao’s death in 1976. By then

China and the CCP were desperately weary of it. In his efforts to reinvigorate

the revolutionary spirit of China, Mao in fact destroyed what was left of it.

His own image was badly tarnished. The CCP was left divided and weakened and

had lost the respect of the Chinese. Thereafter Communist rule in China was

endured rather than supported