In his later years, Montgomery was acutely aware of this

human cost and felt it deeply. In 1967, on the 25th anniversary of the battle,

Montgomery went to Egypt on what would be his last overseas trip. With a former

staff officer, he visited the Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery on the ridge

near Alamein station, which has a clear view of most of the battlefield.

Montgomery had been there on October 24, 1954, when the cemetery was officially

opened, but this visit in 1967 was a more poignant and restrained affair. After

spending considerable time before the headstones of two brothers killed on

successive days, Montgomery quickly left the cemetery. That evening, walking

beside the Mediterranean, Montgomery was silent and subdued. He confessed to

his concerned companion, “I’ve been thinking of all those dead.” That forlorn

feeling, no doubt tinged with a sense of guilt, often returned. In the last

month of his life, Montgomery awoke after a troubled night. He told his friend,

Sir Denis Hamilton, the reason for his disturbed sleep:

I couldn’t sleep last

night—I had great difficulty. I can’t have very long to go now. I’ve got to go

to meet God—and explain all those men I killed at Alamein.

#

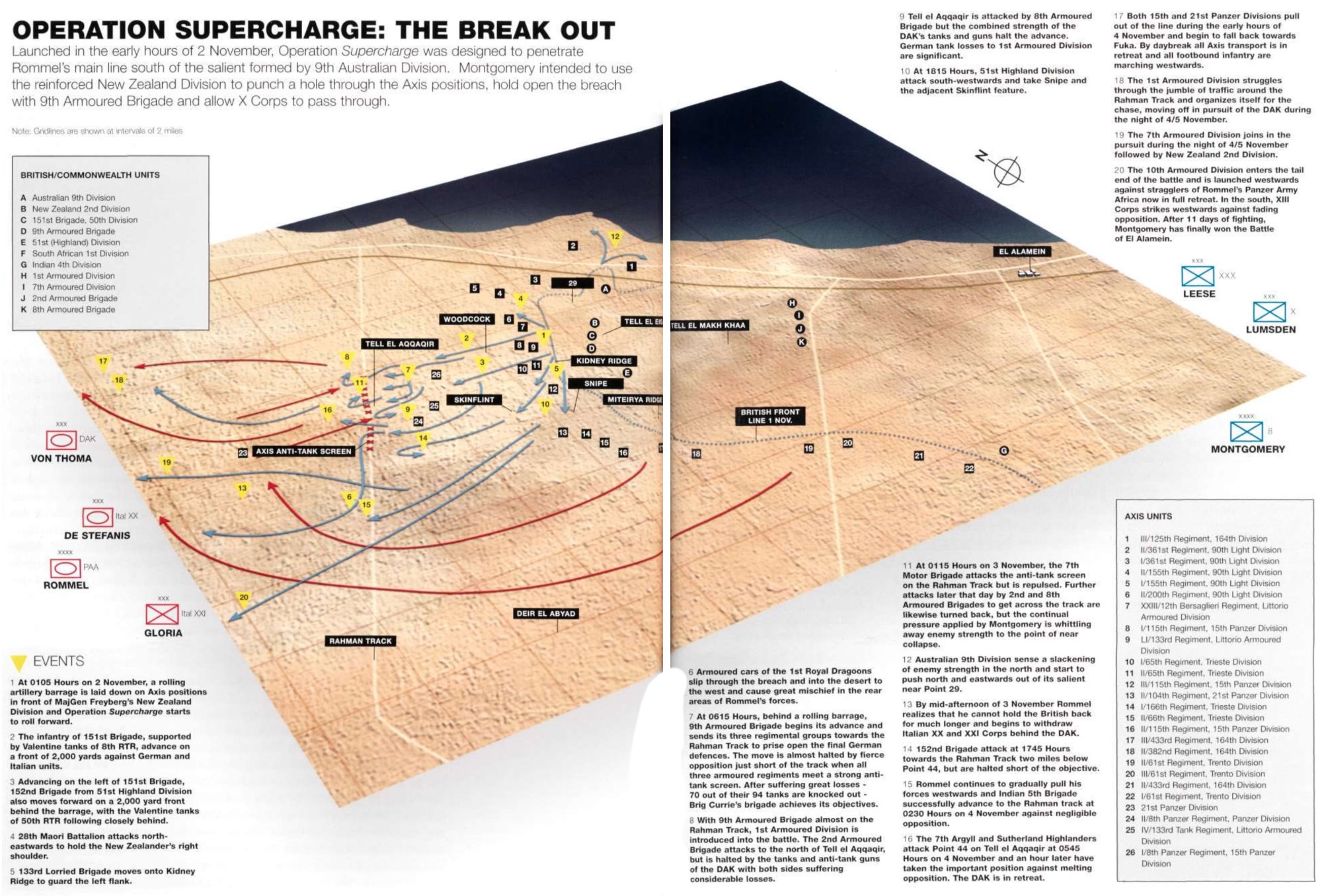

At Alamein, Montgomery demonstrated considerable skill

fighting “with the army he has rather than the one he wants it to be.” When

Lightfoot failed to achieve the break-in and the battle’s momentum was waning,

Montgomery, “resilient but resolute, did not hesitate to change his plan.” The

new plan, Supercharge, while not entirely successful, did enough to break the

will of his skillful opponent. Throughout the battle, despite many anxious

moments, Montgomery radiated “confidence and determination amid all the stress

and urgency.” It was an impressive performance. But despite achieving a

decisive victory, Montgomery never received the accolades, plaudits, or

adulation that his defeated opponent did. As Nigel Hamilton, Montgomery’s

sympathetic biographer, noted with some concern:

Author after author would play down or denigrate Monty’s leadership.

Not only did Auchinleck acolytes feel duty-bound to do so, but non-military

historians waded in, too.

The first book to be

thoroughly critical of Montgomery’s performance as a military commander was

Correlli Barnett’s The Desert Generals. It first appeared in 1960 and “caused a

scandal when published.” It has since been reprinted four times; the last

revised edition appeared in 2007, nearly fifty years after its initial

publication. Barnett’s book was followed by many others all “intent on chipping

away some of the polished marble of Monty’s reputation.”

Conversely, Rommel’s standing as a skilled, daring

battlefield commander, maybe even a brilliant one, has endured, especially

among British and American historians. David Fraser, for example, described

Rommel as “a master of manoeuvre on the battlefield and a leader of purest

quality.” He “stands in the company” of other military greats such as Napoleon

Bonaparte and Robert E. Lee. Ronald Lewin, not quite as praising, ranked him

with Jeb Stuart, Attila, Prince Rupert, and George Patton. For Lewin, who had

been an artillery officer in Eighth Army, Rommel’s place “as one of the last

great cavalry captains … cannot be denied.” For Martin Blumenson, Rommel’s reputation

has only grown since the war. Rommel was “a master of modern warfare” and

undoubtedly a military genius; one of the “great captains who epitomized

generalship on the field of battle.” In a similar vein, Antulio J. Echevarria

II wrote:

Indeed, the decades

since the end of the Second World War have seen historians and other writers

both add to and clear away substantial portions of the Rommel myth. What

remains, however, seems enough to qualify Rommel as one of history’s great, if

controversial, captains—perhaps even a military genius. He did, after all,

defeat a number of able British commanders before the run was broken by

Montgomery at El Alamein.

Rommel’s reputation was not always so high, especially among

those he commanded. Reflecting on what had gone wrong in this last battle, the

Afrika Korps commander, Wilhelm Ritter von Thoma, felt that Rommel deserved

much of the blame. He agreed with Ludwig Crüwell that Rommel “never worried

about anything apart from his own fixed ideas.” But Rommel had other poor

qualities that had contributed to his defeat. He was cocky and overconfident.

Von Thoma described the incident that revealed this serious character flaw:

BURCKHARDT interpreted

when that NEW ZEALAND General [Brigadier George Clifton] was taken

prisoner—I’ve forgotten his name. Field Marshal ROMMEL said: “Tell the General

that the war will be over in six weeks and I shall have occupied CAIRO and

ALEXANDRIA.” BURCKHARDT told me himself that it would have been most painful

for him to have to say such a thing to this General who was standing there so

pensively and had had the misfortune to be taken prisoner in the front line,

which is no disgrace. So he simply said: “You’ll find you are mistaken, Sir.” I

mean later on, if he ever comes to write of his experiences, what will he say about

our appreciation of the situation and our over-confidence? Our tanks were

nothing but scrap-iron. It wasn’t a Panzer Division, it was just miserable

odds-and-ends. To ALEXANDRIA, to CAIRO!

There was more, too. According to von Thoma, Rommel’s battle

tactics “were those of an infantryman…. He took no interest … in all the rest,

that is personnel or supplies, which are the decisive factors for the whole

theatre of war.” Rommel’s reliance on the dense “Minengarten” for protection,

especially when they could not be covered by fire, “was fundamentally

incorrect.” It was a damning indictment of the man who had recently been von

Thoma’s commander, but it was by no means a lone criticism of Rommel. Writing

soon after the war, Generalmajor von Holtzendorff felt that Rommel’s forward

command and aggression made him an excellent Kampfgruppen [combat team]

commander but “seriously impaired his efficiency as an Army commander.” And,

according to Holtzendorff, Rommel never understood how armor should be used:

His attitude toward

the Panzer arm and its employment suffered from the lack of knowledge of its

technical capabilities. This attitude and his constant rejection of material

and fully justified objections on the part of the Panzer commanders repeatedly

caused heavy losses in material (especially Panzers), which then jeopardized

the very idea of the mission.

These criticisms, if valid—and von Thoma was certainly in a

position to know what he was talking about—hardly justify the Rommel “myth” or

the notion that he was one of history’s “Great Captains” or a military genius.

The reality is that Rommel as a military commander was not as exceptional as

some of his biographers have described him, nor was Montgomery the disaster he

has often been portrayed to be.

#

On October 23, 2012, a date that marked a significant

commemoration of the Alamein battles, the United Kingdom’s Daily Mail ran a

story by Guy Walters with a provocative headline. It read: Was Monty’s finest

hour just a pointless bloodbath? Historians claim El Alamein—which began 70

years ago today—sacrificed thousands for the sake of propaganda. The headline,

which probably caused distress to some veterans of the battle, was misleading.

In his article, Walters claimed that “detractors” of the battle’s significance

“maintain that it was a pointless battle in a pointless campaign, fought for

political reasons to boost morale throughout the Empire, and not from any

strategic necessity.” Once again, Montgomery’s generalship was denigrated. He

was described as a “hugely over-rated and unimaginative commander” who “should

never have been raised to the status of national hero.” Walters’ headline is

misleading in that his article, while not naming any of the “detractors,”

actually dismisses their arguments. He concludes:

El Alamein may not

have been an elegant victory, and Montgomery may have been a ponderous general

who was happy to steal much of the credit from the RAF, but it was a battle

that gave the British what it most badly needed—confidence with which to go on

and win the war.

Correlli Barnett had certainly dismissed the October Alamein

battle as pointless. With Operation Torch, the Allied landings in French North

Africa, due to commence in early November, for Barnett this raised “the really

interesting question … why this bitter battle … was fought at all.” Barnett was

emphatic that the “famous Second Battle of Alamein must therefore, in my view,

go down in history as an unnecessary battle.” The hindsight in Barnett’s

judgement is clearly evident. As David Fraser, with the wisdom of experience,

has astutely observed: “In war no man can say how an untried alternative course

of action would have gone, since in war nothing is certain until it is over.”

Some senior military commanders were also dismissive of the

October Alamein battle. The US Chief of Staff George Marshall was one. Marshall

was never impressed with the British campaign in North Africa or with

Montgomery’s generalship. In some off-the-record comments made in 1949, his

interviewers noted:

He [Marshall]

explained that our opinion of the British at that time was not very high in

that the President thought the 8th Army at El Alamein would lose again in the

desert. FDR said to have them attack at night. The General discussed what was

wrong with British command in Africa at some length. He said that the British

in the Middle East [8th Army] had committed about every mistake in the book. It

was no model campaign. The pursuit of Rommel across the desert was slow. The

British even laid a minefield in front of them which benefited the Germans more

than it did the British. Here Marshall formed an opinion that Montgomery left

something to be desired as a field commander. The experience with Montgomery in

northwest Europe confirmed Marshall’s opinion about that.

Even the Chief of the German High Command, Field Marshal

Wilhelm Keitel, was dismissive of Alamein and the North African campaign.

Shortly before his execution at Nuremberg, Keitel reflected on Rommel’s career.

During his interrogation, Keitel had expressed “unlimited admiration of

Rommel’s military achievements and courage.” While Rommel’s efforts in North

Africa had resulted in some “unexpected victories,” this talented commander’s

skills had been wasted there. Keitel wrote, “One cannot help wondering what

this daring and highly-favoured tank commander would have achieved had he been

fighting with his units in the one theatre of war where Germany’s fate was to

be determined.” Clearly, Keitel’s delusions continued to the end of his life.

Rommel and the units he commanded in North Africa would have made no difference

at all to the outcome of Germany’s defeat on the Eastern Front.

The October or second battle of El Alamein was an important

tactical victory for Montgomery and Eighth Army. As Stephen Bungay concluded,

“However one looks at it, in the third round of fighting at El Alamein Rommel

was decisively defeated.” It was “the climax to two years of to-and-fro

struggle in the Western Desert.” And there was a strategic effect to the battle

as well, which transformed it into one of the turning points of the war. A

senior German staff officer at their Supreme Command, the Oberkommando der

Wehrmacht (OKW), recalled after the war that this battle was indeed “the

turning point at which the initiative passed from German into Allied Hands.”

Generalmajor Eckhardt Christian admitted that the OKW “doubtlessly

underestimated Africa’s strategic importance” and that by November 1942, “The

realization of the enemy’s strength and our own weakness came too late to avert

disaster. The enemy now had the initiative and retained it.” Alexander also

wrote of the strategic effect of the battle. There were several reasons why the

battle had to be fought:

In the general context

of our war strategy in 1942, the battle of Alamein was fought to gain a

decisive victory over the Axis forces in the Western Desert, to hearten the

Russians, to uplift our allies, to depress our enemies, to raise morale at home

and abroad, and to influence those who were sitting on the fence. The battle at

Alamein was very carefully timed to achieve these objects—it was not a question

of gaining a victory in isolation.

And as Alexander pointed out, both his knowledge of military

history and his battlefield experience “convince me that a war is not won by

sitting on the defensive.”

Winston Churchill certainly saw the battle as a key turning

point. For him, the October–November Alamein battle was “the turning of ‘the

Hinge of Fate.’” He explained why in two sentences that have become the most

quoted (and misquoted) assessment of the battle’s importance. Churchill wrote

that:

It may almost be said,

[This first part is often omitted] “Before Alamein we never had a victory.

After Alamein we never had a defeat.”

Little wonder then that on Sunday, November 15, 1942, to

mark the victory, the church bells rang all over the United Kingdom. It was the

first time in three years that Britons had heard their church bells ring. The

BBC made a point of recording the bells of Coventry Cathedral for their

Overseas Service. “Did you hear them in Occupied Europe?” a gleeful radio

commentator asked. “Did you hear them in Germany?”

The transformation was far more than a tactical and

strategic shift. This was alluded to in Guy Walters’ conclusion quoted above.

The October–November battle marked a major change in how the British Empire

thought and felt about its warfighting capabilities. It was a critical

transformation. For British soldier and historian David Fraser, the victory at

El Alamein in November 1942 “was the best moment experienced by the British

Army since another November day long ago in 1918.” It meant that “the tide had

finally and irrevocably turned.” When writing about the British defeat in June

1942 during the Gazala battle, which lead to the “deplorable” loss of Tobruk,

Fraser made a profound observation that has often been overlooked by military

historians. Fraser perceived that “battles are won and lost in the minds

of men, and this one had been lost.” To date, the British armies had experienced

few victories and many, costly defeats. There were doubts in the minds of men

and women at the highest and lowest levels whether the British could ever

defeat an army that included German panzer and motorized formations. That doubt

was infectious and had spread to Britain’s allies. The October Alamein battle,

inelegant as all Allied victories in this war were, provided convincing and

much-needed proof that a British army could achieve a victory over German

forces.

After the battle, the Australian commander, Lieutenant

General Leslie Morshead, wrote a revealing letter to a friend. In it, Morshead

highlighted why Eighth Army had won the battle. He also recorded a significant

mind-shift in the Australian soldiers:

It was a very hard and

long battle, twelve days and nights of continuous and really bloody fighting,

and it was not until the last day that the issue was decided. A big battle is

very much like a tug-of-war between two very heavy and evenly matched teams,

and the one which can maintain the pressure and put forward that last ounce

that wins…. I shall always remember going round the line during the battle and

a real digger saying to me “Yes Sir it’s tough all right … but we’ve at last

got these bloody Germans by the knackers.”

The feeling towards the end of the Alamein battle was that

the Germans were on the ropes and losing the battle. The British Eighth Army,

after a hard fight, did at last have “these bloody Germans by the knackers.”

While this sentiment wasn’t expressed in quite so colorful vernacular, it

certainly became infectious. The Alamein battle “was crucial to the morale of

the free world.” The news of Rommel’s defeat at Alamein electrified that free

world. Nigel Hamilton wrote that “the sense of a change in the fortunes of

democracy was palpable.” It signified, as many noted at the time and after, a

crucial shift. The spell was broken and the Germans could be beaten. As the New

Zealand official historian wrote, the battle of Alamein deserves its place in

military history “because it was the first victory of any magnitude won by the

British forces against a German command since the Second World War began.” That

victory transformed the British forces. Instead of doubt, bewilderment, confusion,

and a feeling of inferiority, there was now the strong belief that your side

could fight hard and win. It at last had all the tools to do the job. The long

string of defeats, what Churchill called the “galling links in a chain of

misfortune and frustration,” was finally over.80 The British army, with its

allies, had turned a corner and it was to experience a string of victories,

albeit marked with some setbacks. It had taken a very long time for the Hinge

to turn.