General term for Nahuatl speaking peoples in Pre-Columbian

central Mexico, which connotes “people from Aztlan.” Today the word Aztec is

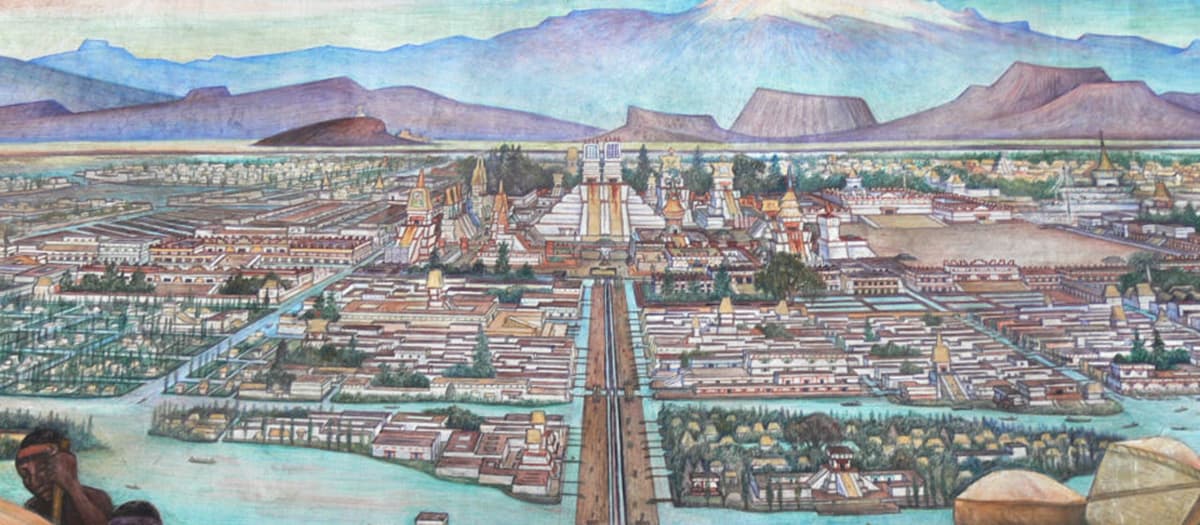

typically used to refer to the Mexica people who resided in the island city of

Tenochtitlan in Lake Texcoco in the Basin of Mexico. The Aztecs are widely

recognized for their imperial political and economic structure; religious

ideology that involves natural elements, ancestors, sacred landscapes, and

human sacrifice; and for their monumental stone art and architecture, which is

routinely uncovered during construction projects in contemporary Mexico City.

The Mexica Aztecs had one of the most powerful states and one of the more

splendid capital centers in all of ancient Mesoamerica.

Of the many deities important to the Aztecs, we know much

about the widely revered Huitzilopochtli, Quetzalcoatl, Tlaloc, Tezcatlipoca,

Coatlique, Xipe Totec, and Coyolxauhqui, which are often mentioned in sources

that date to early colonial times. Aztec art is famous the world over for its

monolithic stone carvings, including the calendar stone and the chacmool,

portable objects carved from jade, feather work, and finely painted and modeled

ceramics. They also created codices, or books, that contained painted images,

but not many hieroglyphs, on bark paper or animal skin. The Aztec capital of

Tenochtitlan was the home of thousands of inhabitants, towering temples, ornate

palaces, ball courts for the bouncing rubber ball game, marketplaces,

tzompantli, or skull racks, irrigated chinampa agricultural fields, and the

residences of the calpulli “clans.”

The Aztecs were newcomers to state politics in central

Mexico during the 13th century when they wandered into the Valley of Mexico (or

Basin of Mexico) while migrating from their original homeland. Here they became

tribute paying vassals and mercenaries of local established states. Through

political intrigue and much success in warfare, the Aztecs eventually gained

their independence and their own tributary towns, agricultural plots, and land

for their capital center. The Aztecs came to power in central Mexico and were

able to expand to other parts of Mesoamerica through the military and political

support of a “triple alliance” between the peoples of the towns of

Tenochtitlan, Tetzcoco (Texcoco), and Tlacopan (Tacuba).

Aztec imperial expansion was driven by the need to acquire

food, materials, and labor for the growing Aztec state and also to obtain the

necessary sacrificial victims on the battlefield to feed the sun during its

daily journey. The Aztecs would subjugate an area by means of military force,

then set up rulership through local elites and allies and ensure their

subordinates’ allegiance and tribute payments with the threat of warfare and by

political and marriage alliances.

The Aztec empire was at its peak and possibly facing drastic

political and economic reform in order to continue making conquests, when the

Spanish conquistadores under Hernan Cortes arrived in A.D. 1519. The Spaniards

were greeted by the Mexica-Aztec ruler Motecuhzoma, who was trying to

consolidate his realm and implement political and economic changes at the time.

Because of military strategy and advanced weaponry, and, critically, through

the help of thousands of indigenous allies (both former friends and enemies of

the Aztecs), combined with the spread of deadly epidemic diseases that

decimated native populations, the Spanish were able to sack Tenochtitlan,

subdue the Aztecs and their last emperor, Cuauhtemoc, and appropriate their

territories by A.D. 1521.

WARFARE

The Aztecs, who became established in central Mexico in the

early 1300s and whose empire flourished from 1430 to 1521, made the last major

weapons innovations. Under their empire, a preindustrial military complex

supplied the imperial center with materials not available locally, or

manufactured elsewhere. The main Aztec projectiles were arrows shot from bows

and darts shot from atlatls, augmented by slingers. Arrows could reach well

over a hundred meters-and sling stones much farther-but the effective range of

atlatl darts (as mentioned earlier, about 60 meters) limited the beginning of

all barrages to that range. The principle shock weapons were long, straight oak

broadswords with obsidian blades glued into grooves on both sides, and

thrusting spears with bladed extended heads. These arms culminated a long

developmental history in which faster, lighter arms with increasingly greater

cutting surface were substituted for slower, heavier crushing weapons. Knives

persisted, but were used principally for the coup de grace. Armor consisted of

quilted cotton jerkins, covering only the trunk of the body, leaving limbs

unencumbered and the head free, which could be covered by a full suit of

feathers or leather according to accomplishment. Warriors also carried

60-centimeter round shields on the left wrist. Where cotton was scarce, maguey

(fiber from agave plants) was also fabricated into armor, but the long,

straight fiber lacked the resilience and warmth of cotton. In west Mexico,

where clubs and maces persisted, warriors protected themselves with barrel

armor-a cylindrical body encasement presumably made of leather.City walls and

hilltop strongholds continued into Aztec times, but construction limitations

rendered it too costly to enclose large areas. Built in a lake, the Aztec

capital of Tenochtitlan lacked the need for extensive defenses, though the

causeways that linked it to the shore had both fortifications and removable

wooden bridges.By Aztec times, if not far earlier, chili fi res were used to

smoke out fortified defenders, provided the wind cooperated. Poisons were

known, but not used in battle, so blowguns were relegated to birding and sport.

Where there were sizable bodies of water, battles were fought from rafts and

canoes. More importantly, especially in the Valley of Mexico, canoe transports

were crucial for deploying soldiers quickly and efficiently throughout the lake

system. By the time of the Spanish conquest, some canoes were armored with

wooden defensive works that were impermeable to projectiles.The Importance of

Organization Despite the great emphasis placed on weaponry, perhaps the most

crucial element in warfare in Mesoamerica was organization. Marshaling,

dispatching, and supplying an army of considerable size for any distance or

duration required great planning and coordination. Human porters bearing

supplies accompanied armies in the vanguard (the body of the army); tribute

empires were organized to maintain roads and provide foodstuffs to armies en

route, allowing imperial forces to travel farther and faster than their

opponents; and cartographers mapped out routes, nightly stops, obstacles, and

water sources to permit the march and coordinate the timely meeting of multiple

armies at the target.What distinguished Mexican imperial combat from combat in

North America was less technological than organizational. More effective

weapons are less important than disciplining an army to sustain an assault in

the face of opposition; that task requires a political structure capable not

merely of training soldiers, but of punishing them if they fail to carry out

commands. Polities with the power to execute soldiers for disobedience emerged

in Mexico but not in North America; those polities had a decisive advantage

over their competitors.In North America, chiefdoms dominated the Southeast

beginning after 900 CE, and wars were waged for status and political

domination, but the chiefdoms of the Southwest had disintegrated after 1200 CE,

and pueblos had emerged from the wreckage. (We use the term pueblos to refer to

the settled tribal communities of the Southwest, but chiefdom is a political

term that reflects the power of the chief, which was greater than that

exercised by the puebloan societies after the collapse around 1200 CE.) There

too warfare played a role, though for the pueblos wars were often defensive

engagements against increasing numbers of nomadic groups. The golden age of

North American Indian warfare emerged only after the arrival of Europeans,

their arms, and horses. But even then, in the absence of Mesoamerican-style centralized

political authority, individual goals, surprise attacks, and hit-and-run

tactics dominated the battlefield, not sustained combat in the face of

determined opposition.

AZTLAN

The mythical homeland from which the Aztec people are

believed to have originated and subsequently left to migrate to central Mexico.

From this original homeland they wandered through northern Mesoamerica until

they reached Lake Texcoco (Tetzcoco) in central Mexico and founded the city of

Tenochtitlan. Aztlan is Nahuatl for “Place of the Herons/Cranes” or “Place of

Whiteness,” and it is said to have been a habitable island in a beautiful lake.

The word Aztec signifies “people from Aztlan,” and this term has been applied

to Nahuatl speakers of Postclassic central Mexico. The Aztecs of Tenochtitlan

referred to themselves collectively as the “Mexica.”

Anthropologists and historians have long tried to locate

Aztlan, or the area in which the mythological place is based, either in central

or west Mexico or in Veracruz, by studying Aztec myth and archaeological

evidence. These areas have numerous lakes and water fowl as described in the

Aztec myth of Aztlan. However, the true location of Aztlan, or the area that

inspired the legend, may never be known. There are conflicting and vague

details from the Aztec chronicles and a number of distinct places seem to be

referred to in the histories. It is also possible that Aztlan is truly

mythological and existed only in Aztec religion and beliefs. Also there are

many sacred “Places of the Reeds,” (Tollan), or additional sites of origin, in

Mesoamerican lore (such as the centers of Teotihuacan and Tula), which further

confuses the search for Aztlan. Even Aztec kings sent out parties in search of

Aztlan, where it was believed communication with deities and ancestors was

possible, but the place, or places, of these visits was never recorded or

definitively identified.

Aztec legend states that their premigration ancestors lived

on Aztlan, an island surrounded by reeds in the center of a large lagoon. The

journey from Aztlan by the Aztecs, who may have been hunters, gatherers, and

incipient farmers earlier on, was initiated and led by Huitzilopochtli, an

important Aztec deity who may have been linked with a historical person and

culture hero/leader.

The Mexica-Aztecs wandered many years throughout Mexico

visiting sacred places, including caves and hills. They overcame obstacles and

arduous tests by supernatural beings to eventually settle in Tenochtitlan,

itself an island surrounded by reeds and herons, which may have helped shape

Mexica-Aztec history, legends, and origin myths concerning “Aztlan” or

“Tollan.” Many Aztec codices, such as the Boturini and Mendoza, illustrate the

Aztec migration from Aztlan and their travels and trials in search of a new

homeland in Mexico.

CODEX MENDOZA.

This book is a crucial source of cultural information on the

preconquest Aztecs of central Mexico. Although this codex was produced in the mid-16th

century and after the Spanish conquest and colonization of Aztec territory, the

images and texts within relate to precontact Aztec warfare and conquests,

customs, social organization, economic structure, and material culture. The

Codex Mendoza was destined for Spain as part of the documentation of the

peoples, lands, local histories, and holdings under the control of the

expanding Spanish empire in the New World. The manuscript changed hands over

the years, and today it is kept at the Bodleian Library at Oxford University.

The multicolored painted images on the folios of European

paper were created by native Aztec scribes commissioned by the Spanish to

record the highlights of Aztec culture and history. Spanish notations and

descriptions of the images were placed right on the manuscript at the time of

its production. The first section of the codex contains an outline of Aztec

history from the founding of their capital at Tenochtitlan to the conquests of

the rulers of the empire. This section contains indigenous calendar dates,

images of people and their name hieroglyphs, and ancient place names and cities

of central Mesoamerica.

The tribute rolls of the conquered polities and territories

make up the second portion of the book. This part has several pages depicting

in vibrant colors the actual tribute items, such as jade beads, jaguar skins,

ceramic vessels, quetzal and other bird feathers, cotton cloaks, foods, and

clothing and their quantities that were delivered to Tenochtitlan. The last

section contains painted scenes from Aztec everyday life, including punishments

of their children, duties of apprentices, marriage ceremonies, occupations, and

captive taking. The combination of the rich imagery created by native scribes,

the Spanish commentary accompanying the designs, and the topics recorded in the

Codex Mendoza make it an invaluable source for the study of ancient Mesoamerica

and the Aztecs.

TLAXCALA

The name of the people and area that was never subdued by

the Aztecs and that became one of the first indigenous allies of the Spanish

conquistadores. Although many archaeological sites remain and much was written

about the Tlaxcalans by the Spanish, comparatively little research has been

done on this region and its Postclassic culture. Many large settlements and

fortified centers are found in Tlaxcala, which is situated between the Aztec

capital of Tenochtitlan and the Totonac area on the Gulf Coast of Veracruz.

The Tlaxcalans successfully repelled repeated attempts at

conquest by their bitter enemies, the Aztecs. However, they had been surrounded

by Aztec enclaves and were surrounded and cut off of critical supplies, such as

cotton cloth textiles and salt for example, upon the arrival of the Spanish.

For these reasons and for the opportunity to become a regional power, the

Tlaxcalans joined the European newcomers marching to conquer the Aztec capital.

The Tlaxcalans also had “flower wars” with the Aztecs in which ceremonial

warfare was undertaken to test army strengths and weaknesses and in order to

take captives for human sacrifice.

TOTONAC

The Totonac people were located in the rich tropical region

of the Gulf Coast of Veracruz, Mexico, near the Huastec Maya and the ancient

ruins of El Tajin and Cempoala. The Totonacs were tribute-paying subjects of

the Aztec empire, and they were organized in small regional states and through

inter-elite alliances. These people were the first defeated in major skirmishes

with the conquering force of the Spanish led by the conquistador Hernan Cortes.

After losing the initial battles with the Spaniards, the Totonacs then became

their first indigenous allies. The Totonacs seized the chance to remove the

Aztec threat and tribute obligation and join the powerful European intruders to

become new rulers of Mexico.

The Spanish placed their first base at Cempoala, a Totonac

city with monumental architecture, palaces, and large plazas. Several

ring-shaped structures built of rounded cobbles with small pillars around their

edges were excavated and restored at this site, and these buildings may have

been used in recording calendar dates and astronomical cycles.

It is not clear if the Totonac people or others built the

city of El Tajin or made stone sculptures and Remojadas ceramic figurines in

central Veracruz or not. Today, the Totonac people still reside in the tropical

rainforests of coastal Veracruz where they entertain visitors at the ruins of

El Tajin as voladores, or men who spiral down from spinning poles with ropes

tied around their ankles.

Further Reading

Andreski, S. (1968). Military organization and society. Berkeley and Los

Angeles: University of California Press. Ferguson, R. B., & Whitehead, N.

L. (1992). War in the tribal zone: Expanding states and indigenous warfare.

Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research Press. Hassig, R. (1988). Aztec

warfare: Imperial expansion and political control. Norman: University of

Oklahoma Press. Hassig, R. (1992). War and society in ancient Mesoamerica.

Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. Hassig, R. (1994).

Mexico and the Spanish conquest. London: Longman Group. LeBlanc, S. A. (1999).

Prehistoric warfare in the American southwest. Salt Lake City: University of

Utah Press. Otterbein, K. F. (1970). The evolution of war: A cross-cultural

study. New Haven, CT: HRAF Press. Pauketat, T. (1999). America’s ancient

warriors. MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History, 11(3), 50-55.

Turney-High, H. H. (1971). Primitive war: Its practice and concepts. Columbia:

University of South Carolina Press. Van Creveld, M. (1989). Technology and war:

From 2000 b. c. to the present. New York: The Free Press