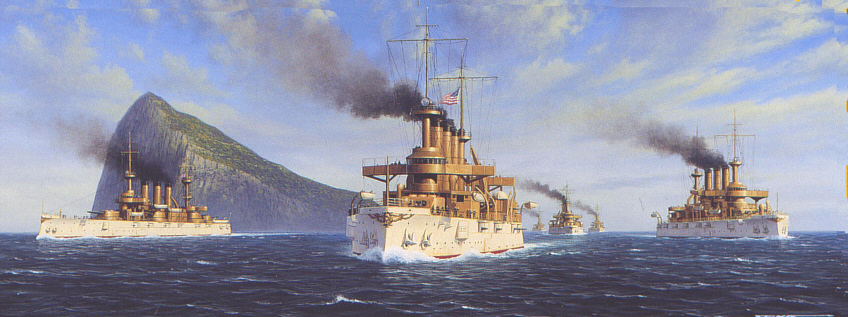

The New Navy

In the 1880s, the U.S. Navy was sufficient for chastising

errant Koreans or Panamanians, but by Great Power standards it was a joke,

ranking twelfth in the world in number of ships, behind Turkey and Sweden,

among others. One midshipman complained in 1883 that his ship, the Richmond,

was “a poor excuse for a tub, unarmored, with pop-guns for a battery and a crew

composed of the refuse of all nations, three-quarters of whom cannot speak

intelligible English.” During a crisis in 1891 caused by an altercation between

some drunk and unruly American sailors and a Valparaiso mob, the Benjamin

Harrison administration was brought to the sobering realization that Chile’s

navy might be more powerful than America’s.

This was an intolerable state of affairs, and the U.S. did

not long tolerate it. The creation of the New Navy began in 1883, during the

Chester Arthur administration, when Congress approved the construction of three

steel cruisers—the Atlanta, Boston, and Chicago—that had partial armor plating

and breech-loading, rifled cannons (as opposed to the smoothbore muzzle-loaders

of old), though they also retained sails to supplement their steam plants.

Three years later, during the first Cleveland administration, the Maine and

Texas, America’s first battleships powered exclusively by steam propulsion,

were authorized by lawmakers.

In 1890, Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan, a 50-year-old

professor at the Naval War College whose long career had hitherto been

distinguished only by his hatred of sea duty and his affinity for alcohol and

high-church Episcopalianism, published a work that would define an age: The

Influence of Sea Power upon History. It both grew out of, and contributed to,

the revolution in naval thinking. Previously the navy had been designed to

protect U.S. shipping and the U.S. coastline and, in wartime, to raid enemy

shipping. Now Mahan urged the U.S. to match the Europeans in building an armada

capable of gaining control of the seas. There was some opposition, including

from the complaisant military establishment, but the critics were pounded into

submission by the rhetorical broadsides fired by Mahan and his influential

friends, a circle that included Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, philosopher Brooks

Adams, Rear Admiral Stephen B. Luce, and, not least, a rising young politician

named Theodore Roosevelt, who displayed his genius for invective by denouncing

“flapdoodle pacifists and mollycoddlers” who resisted the call of national

greatness.

The navalists’ triumph has been much written about but

remains insufficiently appreciated. It was by no means foreordained. In the

late nineteenth century the U.S. faced no outside imperative, certainly no

major foreign threat, necessitating the construction of a powerful navy. Some

historians argue that economic uncertainties—a recession occurred in 1873, a

depression in 1893—gave added impetus to military expansion, as part of a

search for overseas markets. But hard times could just as easily have led to a

contraction of the armed forces and foreign commitments, as they would in the

1930s and 1970s. Instead, in the 1880s and 1890s, Mahan and his cohorts

convinced their countrymen that they should propel themselves into the front

rank of world powers. The result was the first major peacetime arms buildup in

the nation’s history, a buildup that gave America a navy capable of sinking the

Spanish fleet in 1898.

If the U.S. was to have a two-ocean, blue-water,

steam-powered navy, it would need plenty of coaling depots to supply it. The

old sailing navy had enjoyed a degree of freedom from fixed bases that would

not be rivaled until the advent of nuclear propulsion. Square-riggers could go

wherever the winds carried them, repairing and replenishing themselves in

virtually any harbor—even on an undeveloped island like Nukahiva, site of David

Porter’s 1813 landing. Steamers, by contrast, needed assured access to coal and

modern repair facilities. The search for coaling depots had already been a

powerful impetus for colonialism by the European powers, as it was believed

that no navy could ensure access to this vital fuel supply unless it controlled

its own stockpiles scattered around the world. The need for secure coaling

stations would likewise spur American annexations overseas.

The U.S. acquisitive impulse had been building for some time

and, contrary to the popular impression today, did not arrive full grown, as if

by immaculate conception, in 1898. William H. Seward, the great apostle of

empire who served as secretary of state in the Abraham Lincoln and Andrew

Johnson administrations, succeeded in buying Alaska and acquiring Midway Island

in 1867 after it was claimed by Captain William Reynolds of the screw sloop

Lackawanna. He also tried, unsuccessfully, to acquire British Columbia,

Greenland, the Danish West Indies (Virgin Islands), and naval bases at Samaná

Bay in Santo Domingo (the Dominican Republic) and at Môle Saint-Nicolas in

Haiti. Presidents Ulysses S. Grant, in 1869, and Benjamin Harrison, in 1891,

attempted to revive plans to buy Samaná Bay and Môle Saint-Nicolas,

respectively, but nothing came of it.

The U.S. was more successful in expanding its control over

Hawaii. With the signing of a free-trade treaty in 1875, the islands became so

closely integrated economically with the U.S. that they were, in the words of

one senator who voted for the pact, “an American colony.” In 1887 Hawaii

granted the U.S. Navy exclusive use of Pearl Harbor, giving America a

strategically vital Pacific base. In 1893, American residents overthrew the

native queen and asked to join the United States. The local U.S. consul landed

164 bluejackets and marines from the U.S. cruiser Boston, proclaiming the

islands a U.S. protectorate and urging Washington to annex them. The outgoing

president, Benjamin Harrison, signed the annexation treaty. But newly

inaugurated Grover Cleveland looked this gift horse in the mouth; he withdrew

the treaty from Senate consideration. The U.S. would not acquire Hawaii for

another five years, by which time America had become a full-fledged imperialist

power.

Samoa

America’s deepening involvement in Hawaii reflected its

growing orientation toward the Pacific Ocean. As early as 1875 Congressman

Fernando Wood had declared, rather prematurely, “The Pacific Ocean is an

American Ocean.” Well, not quite. But the U.S. was certainly trying to secure

its interests all over the Pacific, and nowhere more so than in Samoa, a chain

of 14 volcanic islands conveniently located midway between Hawaii and

Australia. These islands, populated by 28,000 people in 1881, became the center

of increasingly nasty competition between Britain, Germany, and the U.S. in the

last decades of the nineteenth century.

The first U.S. warship had reached Samoa in 1835, but

America did not become deeply enmeshed in its affairs until 1872, when

Commander Richard W. Meade of the USS Narragansett concluded a treaty with

local chieftains that, in return for extending a U.S. protectorate over Samoa,

granted Washington the right to construct a naval station at the first-rate

harbor of Pago Pago on Tutuila Island. The Senate declined the protectorate,

but in 1878 agreed to take the harbor in return for mediating Samoan disputes

with outside powers. The following year, Germany and Britain demanded and won

similar privileges at other Samoan harbors. Not content with this concession,

Chancellor Otto von Bismarck tried to extend German control over the entire

islands in 1887 by installing a favored candidate on the Samoan throne. When a

revolution broke out, German forces landed, only to be repulsed by the Samoans.

The Cleveland administration was so upset by this act of

German aggression, which threatened America’s Pacific flank, that it sent Rear

Admiral Lewis Kimberly to Samoa with three warships from the Pacific Squadron.

He arrived at the same time as three German warships and one British. All sides

were eyeing one another warily when, on March 15, 1889, a mighty hurricane

ravaged Samoa, wrecking almost all the foreign warships in the harbor,

including the bulk of America’s Pacific Squadron. The war fever was literally

blown away, at least temporarily.

Instead of fighting, the three powers negotiated and in 1889

agreed to divide control of Samoa among them, just the sort of “entangling

alliance” the U.S. once would have rejected. Nine years later the old king of

Samoa died and a civil war broke out pitting the followers of Mataafa, the

German candidate, against Malietoa Tanu, the Anglo-American choice. Mataafa

gained control of the government—but not for long. Viewing Mataafa’s usurpation

as a violation of the 1889 Treaty of Berlin, U.S. Rear Admiral Albert Kautz,

aboard the cruiser Philadelphia, coordinated a counterattack with the Royal

Navy. In the interest of unity of command, some American sailors were placed

under the command of British officers and some British bluejackets were placed

under the command of American officers.

On March 13, 1899, an American landing force was put ashore

to begin the occupation of Apia. On March 15 and 16, the USS Philadelphia along

with HMS Royalist and HMS Porpoise bombarded the area around the towns of Apia

and Vailoa, targeting Mataafa’s followers but also hitting, allegedly by

accident, the German consulate and a German gunboat. On March 23, wearing an

ill-fitting British naval officer’s dress uniform and borrowed canvas shoes,

Malietoa Tanu was crowned king of Samoa under the protective guns of the

Anglo-American force. But far from surrendering, the followers of Mataafa, the

German-backed pretender, fired into Apia from the bush and constantly

skirmished with U.S. and British troops. The Anglo-American forces found it

relatively easy to operate along the shoreline, where they could be covered by

naval guns, but on April 1, 1899, they made the mistake of leaving the safety

of shore to pursue Mataafa’s followers inland.

Sixty Americans joined 62 Britons and at least 100 of Tanu’s

men on this expedition, commanded by Lieutenant A. H. Freeman of the Royal

Navy. They were ambushed by Mataafa’s men firing guns from well-prepared

positions in the tall grass. The Anglo-American soldiers put great store by

their machine gun; in the past, the Samoans had fled in terror before its bark.

This time, however, the Colt gun jammed, Westerners began dropping, and it

looked likely that the column would be annihilated. U.S. Marine Lieutenant

Constantine M. Perkins organized a desperate rearguard action around a wire

fence, holding off the Mataafans long enough for the column to retreat to the

beach, where it was saved by covering fire from HMS Royalist. It was only then

that they discovered that two American officers and one British officer were

missing. The following day the three men were found buried, their heads and

ears cut off. In all, four Americans were killed and five wounded in this

expedition. Three marines received the Medal of Honor for their bravery on

April 1.

The British and Americans continued their sorties and

bombardments against the Mataafans until April 25, 1899, when word arrived that

Mataafa had agreed on cease-fire lines. An international commission

subsequently ended tripartite rule in Samoa, dividing the islands between

Germany and America, with Britain receiving compensation elsewhere. The U.S.

won title to the island of Tutuila, where the navy set about building a coaling

station. In World War I, an expedition from New Zealand expelled the Germans

from western Samoa; the islands became independent in 1962. American Samoa

never achieved much strategic importance, but it remains part of the United

States to this day.

The larger significance of the Samoan adventure is twofold.

First the U.S. was abandoning the old strategy of “butcher and bolt”; now U.S.

forces were staying in foreign countries and trying to manipulate their

politics, if not annex them outright. Normally this practice is known as

imperialism, even though Americans, belonging to a country born of a revolt

against an empire, are sensitive about applying this term to their own conduct.

There is no doubt that at least one American would have been delighted to see

this development, if only he had lived so long. The dreams of Commodore David

Porter—America’s first, frustrated imperialist—were starting to be realized.

A second and perhaps related point is that American troops

in distant lands were now encountering much more substantial opposition than

they had in years past, due to the diffusion around the world of Western

ideals, such as liberalism and nationalism, and Western technology, such as

rifles and cannons. In 1841, Lieutenant Charles Wilkes’s men had burned three

villages and killed countless Samoans without suffering any casualties.

Fifty-eight years later, Admiral Kautz’s party was almost annihilated by

Samoans firing rifles with great accuracy. After a cease-fire had been declared

and a weapon buy-back program instituted, the Samoans turned over 3,631 guns.

This was the start of a trend: During the Boxer rebellion, German marines would

be killed with Mauser bullets and Krupp artillery. America had the misfortune

of joining the imperial game just as it was becoming more dangerous.