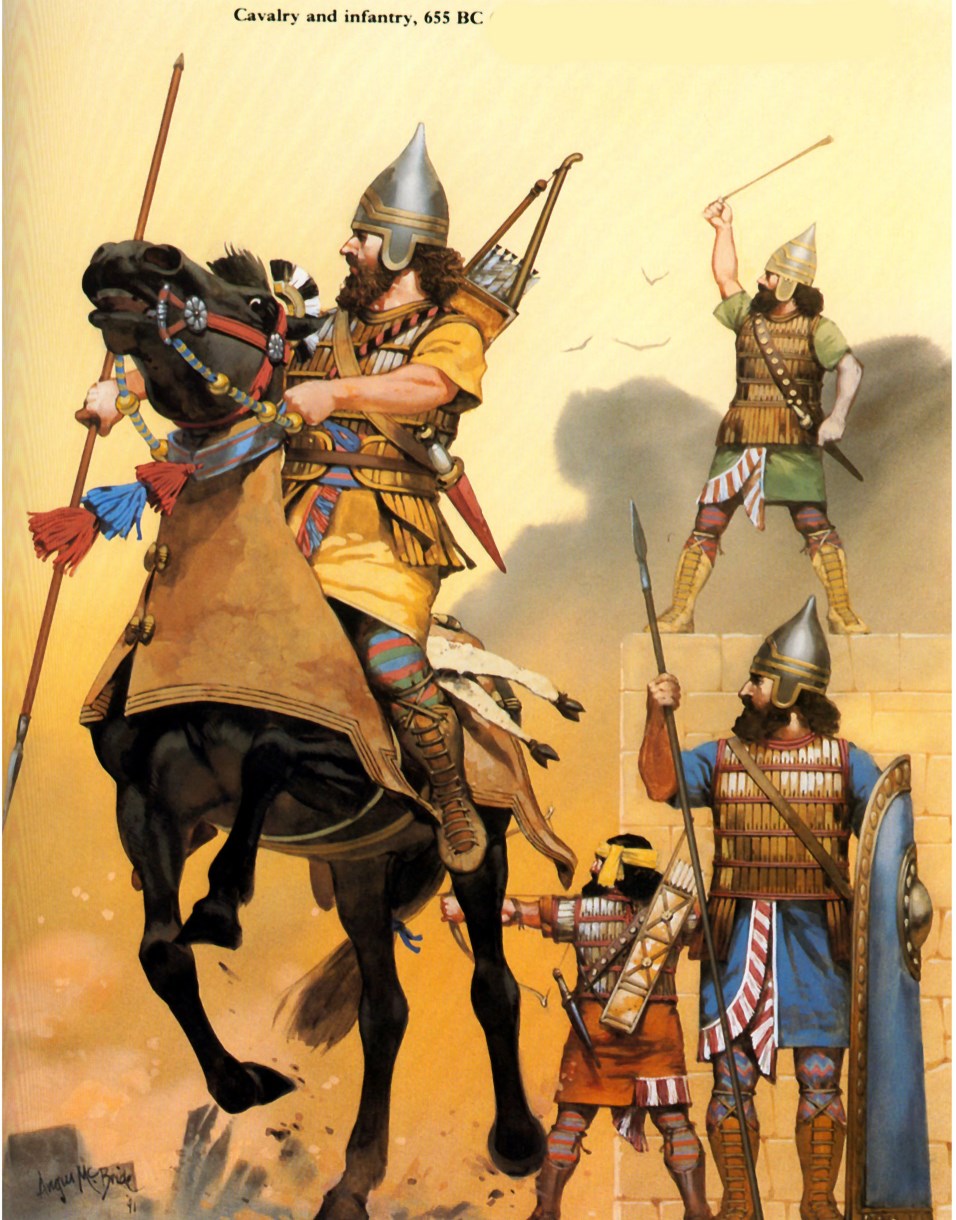

During Sargon’s reign, the importance of cavalry increased a

great deal due to the army’s growing need for mobility over the rough terrain

north along the upper Tigris and in the Taurus regions, and east into the

Zagros Mountains. Horse soldiers wore robes (hiked up in front for ease of

movement), leggings, and boots, but no armor other than a standard conical

Assyrian helmet of iron or bronze. At this time, riders carried lances, short

swords, and bows. Although the Assyrians had neither saddles with girth straps

nor stirrups, they developed a good bridle-and-rein system that allowed

horsemen to fight at the gallop without losing control of their mounts. Before

the invention of the rein holder, bareback riders lacked the ability to

discharge a bow without dropping their reins. In the ninth century the

Assyrians solved this problem by having cavalry operate in pairs, with one

rider to hold the reins of both horses, while the other shot his bow. By the

late eighth century, horsemen rode singly. Nevertheless, while Sargon’s cavalry

are depicted on the reliefs carrying encased bows, they never appear shooting

while galloping. It seems likely, therefore, that Sargon’s reign marked a

period of transition for the cavalry.

Since the mounted divisions were essential to maintaining

Assyria’s military edge, the acquisition and care of horses and mules were top

priorities. The Assyrian army needed several different types of horses. Large

and hardy, Kushite horses from Egypt made excellent chariot teams, whereas

smaller horses from the Taurus and Zagros pasturage were especially desirable

as cavalry mounts. Horses acquired through trade, tribute, and war fell under

the purview of the chief eunuch, as did control of the system based on the

regular tax collection scheme that assembled them for military use. In the

off-season, the army distributed mounts to their riders, who would pasture and

attend to them, while the recruitment officers (musarkisani) oversaw the

process and made sure that the horses received fodder and the men remained

battle-ready. At muster time in each province, two of these officers together

with a subordinate team commander (rab urate) or cavalry prefect (saknu sa

pethalli) organized both horses and soldiers for the mounted units of the

standing army. Recruitment officers delegated horses to the cavalry and

chariotry, put some out to pasture in reserve, or occasionally assigned them to

work as draft horses in public building projects. Another class of high

official, the stable overseers (saknute sa ma’assi), was in charge of horse

care for all equestrian units on campaign. In addition to this system-perhaps

for emergency needs-larger herds of horses were kept on estates in the

provinces under the care of provincial governors and probably in special state-run

pasturage in the heartland.

The central government put a lot of effort into making sure

the army had an adequate supply of horses and pack animals (mules and sometimes

camels), but the job was not an easy one. The royal correspondence attests that

sometimes people had to be coerced into contributing their assigned allocation.

For example, in answer to Sargon’s query about the availability of a particular

kind of horse, one provincial official replied: “I sent the servants of

the king, my lord, to the town, Kibatki. They became frightened and they put

people to the iron sword. After terrorizing Kibatki, they got afraid and wrote

to me, and I set a deadline for them.” In another case the palace

instructed several officials assembling cavalry under emergency conditions:

“Get together your officers plus the h[orses] of your cavalry contingents

immediately! Whoever is late will be impaled in the middle of his own house,

and whoever changes the [ . . . ] of the city will also be impaled in the

middle of his house and his sons and daughters will be slaughtered by his

order. Do not hold back; leave your work, come right away!” Given how

rarely this type of threat appears in the royal correspondence, it is likely

that Sargon included it to emphasize the urgency of the situation, though

clearly the king expected immediate results and felt able to threaten his

subordinates as necessary.

The availability of food and fodder for the equestrian

divisions was also a frequent subject for complaint in letters to the king, as

provincial governors had difficulty providing enough for the army without

inflicting shortages on their own men. Lower-ranked officers met similar

problems as they tried to supply their men and mounts. One letter, written to

Sargon from the governor of Supat (in Syria), recounts a conflict over fodder:

The king, my lord,

ordered [me to] give bread to the grooms. Now [PN] came (and) I told him [ . .

. ] but he said: “The king has given orders to me and I will take two [ .

. . ] of each (provision).” I did not agree; I did not give it to him, so

he went into one of my villages, opened a silo, brought in his measurers and

piled up (grain) for [x] healthy men. I went and spoke with him, saying:

“Why did you by yourself, [with]out the deputy, open the king’s granaries?”

He would not look me in the eye [but said]: “In the month of Nisan my

fodder (supply) fell, and the horses are collapsing (before) me; I [can]not

[manage]

.”

Another official, while waiting for king’s men to muster in

the northern Habur region, noted, “The horses of the king, my lord, had

grown weak, so I let them go up the mountain and graze there.” In a world

subject to every vicissitude of nature, the management of food and fodder for

large numbers of people and animals presented a serious challenge. Facing

similar obstacles, the regular infantry formed the backbone of the king’s army.

The Standing Army:

Infantry

Armored spearmen and archers recruited from the home

provinces and men recruited from the elite infantry of certain conquered states

(e. g., Shinuhtu and Samaria), made up the Assyrian heavy infantry of the

standing army. These soldiers wore the standard conical helmet and metal or

leather scale armor over a knee-length tunic. Officers often carried a mace as

a symbol of office and for coercive purposes, albeit probably not as a

battlefield weapon. The reliefs do not show any Assyrian using a mace in

battle. Additionally, archers and spearmen carried short swords or daggers, but

for obvious reasons only the latter carried shields. There is no evidence for

slingers during Sargon’s time, although they became prominent in the army

later.

Auxiliaries made up the standing army’s light infantry

divisions, each with its own distinctive costume and weaponry. The light

archers, the Itu’, represented an Aramaean tribe that inhabited central

Mesopotamia. After Tiglath-pileser III finally pacified them around 738,

members of the tribe formed a permanent corps of the Assyrian army. Text

references show that under Sargon other Aramaean tribes such as the Hallatu,

Rihiqu, Litanu, and Iadaqu sometimes served as auxiliary archers as well,

though only the Itu’ served continuously. On the palace reliefs, auxiliary

archers always appear bare-chested and barefoot, dressed in short kilts, and

wearing headbands to control their long hair. Though primarily serving as

archers, they are occasionally shown using a dagger to dispatch an enemy in the

aftermath of battle. Commanded by an Assyrian officer (saknu), the Itu’ean

auxiliaries nonetheless retained some tribal organization under the subordinate

leadership of chiefs and village headmen. The Gurrean auxiliaries fulfilled

somewhat different tasks.

So far it has been impossible to identify the Gurreans’

place of origin, but based on their distinctive crested helmet and light armor

it is generally agreed that they hailed from a wide area along the northern and

northwestern frontier of Assyria; that is, northern Syria and central Anatolia.

The term “Gurrean” seems to have been used broadly as an ethnonym and

military designation rather than a specific tribal name, and texts suggest that

these soldiers served under the sole command of Assyrian officers. In battle

each wore a crested helmet, a small chest plate (sometimes referred to by the

Greek term kardio-phylax), a knee-length tunic, and usually boots. They carried

spears (their weapon of preference, judged to have been about eight to nine

feet long), short swords, and round bucklers made of woven wicker or leather.

As part of the standing army, the auxiliaries owed loyalty

only to the king, who often allocated them for duty in the provinces. Auxiliary

troops-especially the Itu’ean archers-were in high demand as a kind of mobile

military police to help with internal security and peacekeeping, border patrol,

and intelligence gathering. The governor of Ashur, for example, once wrote to

Sargon asking for Itu’eans to oversee some workers in his absence: “The

governor of Arrapha has 100 Itu’eans standing guard in the town of Sibtu. Let

them write to the delegate of Sibtu and let 50 (of those) troops come and stand

with the carpenters until I return.” Both types of auxiliaries made up a

significant portion of the army on campaign. On the Dur-Sharrukin reliefs,

Itu’eans and Gurreans appear in nearly every combat or siege scene, and it is

clear that they were an integral part of Sargon’s standing army.

The Provincial Army: Levies

In Assyria all adult males were eligible for annual

temporary service (ilku) in the army or to do work for the crown. If there were

any formal criteria for eligibility, such as age and physical condition, they

are not known, though texts reveal that even very young boys sometimes served,

probably as substitutes for older family members or richer men who bought

themselves out. Presumably, the local village headman along with the

recruitment officer decided whether individuals were fit for duty, though how

strict they were about it probably depended on the quota they had to fill.

Levies served as infantry, cavalry, and possibly as chariot drivers and

“third men.” Among those who apparently counted as king’s men and

mustered for seasonal service was an ambiguous group called kallapu (plural

kallapani) that appears to have formed in the eighth century after the adoption

of a rein-holding device obviated the need for cavalry to ride in pairs, with

one to fight and one to hold the reins. Having been made redundant, the former

rein-holders became a new unit called kallapani that functioned as lancers or

as a type of dragoon (mounted infantry). These troops performed a wide variety

of duties, including serving as the army’s vanguard or rearguard (or both), reconnaissance

men, foragers, sappers, MPs (to keep levies in line), and guards for royal

messengers. As the lowest-ranking soldiers, seasonal levies receive relatively

little attention in Sargon’s texts and sculptured reliefs.

Notes on Arms and

Armor

Excavated examples of arms and armor dating to the late

Assyrian period reveal a great variety in materials and construction and little

uniformity, though certain trends emerge. As we have seen, the main weapons of

the Assyrian army were spears and bows, and since both were made almost

entirely of perishable materials, few traces of which have survived, analysis

rests on the interpretation of blades and metal points. Despite being more

expensive than bronze, harder to work, and requiring a long process of carburization,

hammering, and quenching, iron was the preferred metal for swords and daggers,

probably because it was strong and could be sharpened and re-sharpened easily.

Iron did not entirely eclipse the use of bronze for the manufacture of military

equipment, however. Lighter weight than iron, bronze was suitable as shield

covering and for helmets, and, because it could be recast repeatedly, it proved

particularly appropriate for the speedy production of arrowheads and spear

points. Scale armor made of bronze, iron, or perhaps leather provided body

protection.

Bows depicted on the reliefs appear to have been a

composite, recurve type constructed of wood, bone, and sinew strips glued

together. Estimations based on the length of surviving spear points suggest that

shafts were about nine feet long and that both infantry and cavalry used them

for close-quarter combat rather than for throwing. Judging from the reliefs and

the size of the extant examples of swords and daggers, which are all quite

short-no sword exceeds forty-five centimeters in length-the Assyrian soldiers

used the double-edged blades should their primary weapon fail or to finish off

defeated enemies in the aftermath of battle. Short swords, daggers, and spears,

used for stabbing rather than slashing, delivered killing blows more

effectively, penetrating stab wounds invariably being more deadly than most

surface cuts. These blades also functioned as handy tools comparable to the

modern marine’s KA-BAR knife or a Gurkha’s kukri, both of which are famous for

their versatility as murderous weapons, entrenching tools, and path-breaking

implements. Indeed, on Assyrian reliefs, sappers are often shown using their

blades to undermine the walls of besieged towns, while on at least one occasion

soldiers use their daggers to butcher animals.

Since few datable examples of shields have survived, most

information comes from the reliefs, according to which Sargon’s army utilized a

number of shield types fashioned from various materials: large, round shields

made of bronze or possibly wood reinforced with bronze bands; smaller round and

rectangular combat bucklers, probably made of densely woven wicker or leather;

and full-length tower shields curved at the top and composed of the same woven

material. All shields had one central handgrip. The material evidence, such as

it is, suggests that Sargon’s army was as well-equipped as possible at the

time. On campaign, accompanying craftsmen replaced or repaired the equipment

that they could, while plundering soldiers carefully fieldstripped weapons and

armor from dead enemies for reuse. The arms and armor plundered from captured

cities that the king did not dedicate at a temple or award to the magnates

filled the storerooms of a review palace (ekal masarti) for future use.

The Army on Campaign

The Assyrian army has often been portrayed as a mercilessly

efficient fighting machine capable of overwhelming any obstacle, but the

reality was much more commonplace and involved a great deal of human effort,

effective planning, and strenuous physical labor. Warfare was seasonal, with

the likelihood of good travel weather and the availability of food and water

determining the duration of campaigns as well as campaign route. After careful

planning throughout the winter, campaign season began in late spring or early

summer with the annual muster, which could take a month or more to complete. A

complicated process, the muster involved constant communication between

governors, officials overseeing troop movements and logistical arrangements, and

the king. A recruitment officer or cohort commander collected the enlisted men

in the area assigned to him and then decided which recruits were fit to serve

and which should stay in reserve. Once he had gathered his troops, he delivered

them to his immediate superior, a prefect or a provincial governor, who marched

them to a review palace (armory) or a destination closer to the area of

operations. The Assyrians used the review palace “to maintain the camp

(and) to keep thoroughbreds, mules, chariots, military equipment, implements of

war, and the plunder of . . . enemies; . . . to have the horses show their

mettle (and) to train with chariots.” These large, fortified complexes at

Calah and Dur-Sharrukin could board three thousand or more horses. At the muster

point, troops trained before being outfitted with such items as armor, packs or

saddle bags, cloaks, tunics, water skins, sandals, and reserve food rations,

according to the requirements of their specific units.

Much of the time, assembly went smoothly, as evidenced in a

report from an official on the northeastern frontier, who calmly assured the

king that “I will assign my king’s men, chariots and cavalry as the king

wrote to me, and I will be in the [ki]ng my lord’s presence in Arbela with my king’s

men and troops by the [dea]dline that the king, my lord, set.” Fulfillment

of manpower obligations could be onerous for the officials involved, however.

Several letters complain about the quality of recruits and indicate that the

crown’s demands sometimes met with resistance at the local level. In a report

to Sargon, for example, one official protested, “I wrote to the king, my

lord, but only obtained [2]60 horses and [x number] of little boys. [2]67

horses and 28 men-I have 527 horses and 28 men altogether. I keep writing to

where there are king’s men, but they have not come.” Other officers

grumbled about men being late for a muster or avoiding duty completely. One

frustrated official confessed, “My chariot fighter [cal]led Abu-[ . . .

]-for the second year [ . . . ] has not g[one on] campaign with me.” A

similar dispatch, in which an official testified that “[120] king’s men

who did not go on campaign with the king are in the presence of the governor of

Arbela; he does not agree to give them to me,” suggests that high-ranking

officers were sometimes loathe to turn their troops over to someone else,

especially someone who might be regarded as a competitor.

The Assyrians obliged clients and allies to send men on

campaign when required. Here too calls for troops were sometimes greeted with

passive resistance. For example, Sharru-emurani, the governor of the Assyrian

province Zamua, in the Zagros foothills, wrote to Sargon: “Last year the

son of Bel-iddina did not go with me on campaign but kept the men at home and

sent with me young boys only. Now may the king send me a deportation officer

(literally “mule-stable man”) and make him come forth and go with me.

Otherwise, he will (again) rebel, `fall sick,’ shirk, and not [go] with me, but

will send only l[ittle] boys with me (and) hold back [the best men].”

Foreign contingents or mercenaries could be difficult for Assyrian officers to

control, and there are several letters regarding unruly soldiers. One officer,

writing from Arbela, protested that “the Philistines whom the king, my

lord, organized into a unit and gave me, do not agree to stay with me,”

while another official indignantly reported troops “loitering in the

center of Calah with their mounts like [ . . . ] common thugs and

drunkards.” Unsurprisingly, most of the letters saved in the permanent

archives were those that reported problems rather than those that merely

confirmed positive results, and we should be cautious about reading too much

into them. Nonetheless, complaints of shirking, delay, dereliction of duty, and

occasionally overt resistance to imperial authority evince themselves with

striking regularity.

Since muster lists are incomplete and no text explicitly

states how many men went on a given campaign, it is impossible to determine the

size of Sargon’s army accurately. Based on ration information given in a couple

of letters, one scholar tentatively reckons that the Assyrians could have raised

an army of thirty-five thousand to forty thousand for large operations. Muster

lists dating to the period 710-708 tally more than twenty-five thousand men

available for active duty or held in reserve, thus indicating the minimum size

of the force during that time. Given the logistical constraints under which the

army operated, it seems most likely that it seldom exceeded thirty-five

thousand and more commonly amounted to fewer than twenty thousand men.

Scattered epistolary evidence suggests that the Assyrians experienced chronic

manpower shortages, especially when soldiers had to be removed from garrison

duty to go on campaign. In one instance an unidentified author explained that

he could not send two thousand men to the royal delegate at Der as requested, because

“the men from here do not suffice (even) for the fortresses! Whence should

I take the men to send to him?” Moreover, the construction of the new

royal capital, Dur-Sharrukin, drained manpower and material resources from the

provinces to the point that governors had a difficult time fulfilling work

quotas while maintaining provincial security and military readiness. With

mounting frustration the palace herald, Gabbu-ana-Ashur, wrote to Sargon

protesting that “all the straw in my land is reserved for DurSharrukin (to

make mud bricks) and my recruitment officers are now running after me; there is

no straw for the pack animals.” He went on to demand irritably, “Now

what does the king, my lord, say?” The conquest of new territories, while

theoretically expanding the recruit pool, inevitably put additional stress on

the standing army, though the real problems arose after the army left the

muster area.