But Churchill had put his finger on the bigger issue in his

memorandum to the Committee of Imperial Defence for the meeting on 23 August

1911: what was the strategic role of the BEF? In the discussion at that meeting

on the BEF’s status of command, Reginald McKenna, the then first lord of the

Admiralty, had suggested that ‘if a British force were to be sent at all, it

should be placed under French command’. Perhaps McKenna knew that this would

not be palatable to the general staff (which indeed it wasn’t, as Henry Wilson

at once protested), thereby advancing the cause of the naval option; but in any

case, ‘Mr Churchill dissented emphatically’, say the minutes: ‘The whole moral

significance of our intervention would be lost if our Army was merely merged in

that of France.’

This was a moot point – perhaps Churchill was thinking of

his illustrious ancestor’s difficulties with the Dutch field deputies in the

war with France – but it needed mooting nevertheless: how was Britain to exert

the greatest moral effect – and, implicitly, at the lowest cost? But there was

more at stake than this. The question was really what was to happen after the

Germans had invaded; for, having the initiative and therefore being able to

concentrate, they would certainly force the frontiers at one point or another.

Churchill had grasped the difference between merely winning battles and winning

the war: ‘France will not be able to end the war successfully by any action on

the frontiers. She will not be strong enough to invade Germany. Her only chance

is to conquer Germany in France’.

This, he said, would mean the French accepting invasion,

including even the investment of Paris, but such a policy might depend on

knowing that the British would be coming to France’s aid on land – which, by

return, would depend on our knowing what were the French intentions. This was,

of course, a view entirely at odds with that of the French general staff, who

did indeed envisage the invasion of Germany, or at least, certainly to begin

with, that former French territory occupied by Germany (Alsace-Lorraine) –

which for a few days in August 1914 was largely what happened. However,

Churchill’s bold assertion was based on the calculation that by the fortieth

day of mobilization.

Germany should be

extended at full strain both internally and on her war fronts, and this strain

will become daily more severe and ultimately overwhelming, unless it is

relieved by decisive victories in France. If the French army has not been

squandered by precipitate or desperate action, the balance of forces should be

favourable after the fortieth day [and improving] … Opportunities for the

decisive trial of strength might then occur.

It could easily be supposed that this memorandum had been

written in late 1914 rather than the summer of 1911: the fortieth day of German

mobilization was 9 September, the day the BEF crossed the Marne on its way to

the Aisne. Historians have sometimes commented on Churchill’s prescience, but

none has ever fully examined his conclusion that the French must accept

penetration of the borders and organize to defeat the Germans thereafter, the

part the BEF might play in such an operational plan, and the possible outcome.

So how did Churchill see the BEF’s contributing to these

‘opportunities for the decisive trial of strength’?

In short, by generating a BEF that could act decisively

‘instead of being frittered into action piecemeal’ – the argument, indeed, that

Haig was making at the time of the 5 August war council, and in his preceding

letter to Haldane: ‘so that when we do take the field we can act decisively’.

Churchill envisaged the immediate despatch of a BEF of four divisions plus the

Cavalry Division, for its ‘moral effect’, to be joined by the two remaining

divisions ‘as soon as the naval blockade is effectively established’ (and the

threat of invasion thereby ended). These would assemble not at Maubeuge for

incorporation in the French line of battle, but well to the rear, at Tours,

more or less equidistant between St Nazaire and Paris. As soon as the colonial

forces in South Africa could be mobilized, the 7th Division would be recalled

from there and its stations in the Mediterranean. To these would be added 15,000

Yeomanry and TF cyclist volunteers. And – perhaps the greatest gamble (though

in fact it would eventually happen) – six out of the nine divisions of the

Indian Army could be brought to the BEF, ‘as long as two native regiments were

moved out of India for every British regiment’ (Churchill was as aware as any –

and more than most – of the peculiar mathematics and chemistry of the Indian

Army): a further 100,000 troops, ‘brought into France via Marseilles by the

fortieth day’.

In total, by 14 September this would have furnished a BEF of

some 290,000 (Haig had written to Haldane of 300,000), which the actual arrival

of the 7th and 8th Divisions and the Indian Corps before Ypres shows was

perfectly possible. And, although Churchill does not mention it, there would

also have been time to assemble additional heavy artillery.

But what, meanwhile, of the gap which a BEF at Tours would

have left in the French line of battle? In his letter to Haldane, Haig had made

the filling of this gap, so to speak, a fundamental assumption: ‘I presume of

course that the French can hold on (even though her forces have to pull back

from the frontier) for the necessary time for us to create an army …’

The answer lay with the nine French divisions – two corps –

earmarked for the army of observation on the Italian border. These could have

been put at notice to move as soon as the Italians declared their neutrality on

3 August (a decision confirmed to the second war council by Grey on 6 August),

and the move begun as soon as French intelligence could confirm that the

Italian army, although recalling some reservists to the colours, was not moving

to a war footing (Austria was, after all, the more recent enemy, and France the

ally: there was every reason for Rome to fear an Austrian grab in Venezia). If

such a redeployment sounds injudicious – perilous even – in the event this is

what did indeed happen: the French Army of the Alps was stood down on 17 August

(at which time much of the BEF was still encamped near their ports of landing).

Though it would have been a last-minute affair, its six in-place divisions

(five of them regular), which were surplus to Plan XVII, would have been

available to re deploy to the left of Lanrezac’s 5th Army, where, indeed, the

erstwhile commander of the Army of the Alps, d’Amade, had already been sent to

take command of the Territorial divisions. The great advantage that the French

enjoyed – though they failed to make full use of it – was that the Schlieffen

Plan unfolded at walking pace, and on exterior lines, observable by air, while

the strategic movement of French troops, on interior lines, could be conducted

at the speed of the railway engine. Never, before or since, has a

commander-in-chief had so much time in which to make his key decisions. That is

the real import of A. J. P. Taylor’s quip about ‘war by railway timetable’ –

not that Europe’s leaders were forced into war by movement schedules. The Elder

Moltke had said it to Bismarck: ‘Build railways, not forts.’

If these dispositions had been made, there is no reason to

suppose that the situation at the end of September would have been any

different from that which actually transpired – with French forces mounting a

successful counter-attack on the Marne, and then the stalling on the Aisne.

There was an undoubted moral effect in having the BEF in the line, and it

certainly ‘punched above its weight’, but it is unreasonable to suggest that

the French would not have been able to manage things on their own if they had

been able to replace the BEF with the same number of their own regulars.

Joffre, seeing the enemy, as it were, off guard, had brilliantly improvised and

delivered a blow on the Marne that had sent the flower of Brandenburg reeling;

but it was not enough. In the terminology of modern doctrine, he had executed

the first two of the four requirements of victory – ‘find’ and ‘fix’: he had

found the weak point, Kluck’s and Bülow’s flank, and he had fixed them –

temporarily (which is all that can be expected) – on the Aisne. What he then

had to do was ‘strike’ and then ‘exploit’ (as suggested by Churchill’s ‘Her

only chance is to conquer Germany in France’).

However, at the time of launching the counter-offensive on

the Marne Joffre had not been able to create a striking force to exploit

success. What he needed was what the BEF could have offered had it been allowed

to build its strength at Tours – a fresh, strong, virtually all-regular army

numbering nearly 300,000. It should have been the winning move.

Not, however, simply to attack on the Aisne, to apply more

brute force where brute force had already exhausted itself. What was needed was

overwhelming force applied as a lever rather than as a sledgehammer. The German

flank was not just open in a localized way after the retreat to the Aisne; the

entire Schwenkungsflügel – the ‘pivot’ or ‘swing’ wing – was extended in an

east–west line through mid-Champagne and southern Picardy, and it was beginning

to bow back on the right. Indeed, with each successive encounter on the

extremity of the flank, even as the Germans brought up new troops, the line

backed further north rather than projecting further west. In the third week of

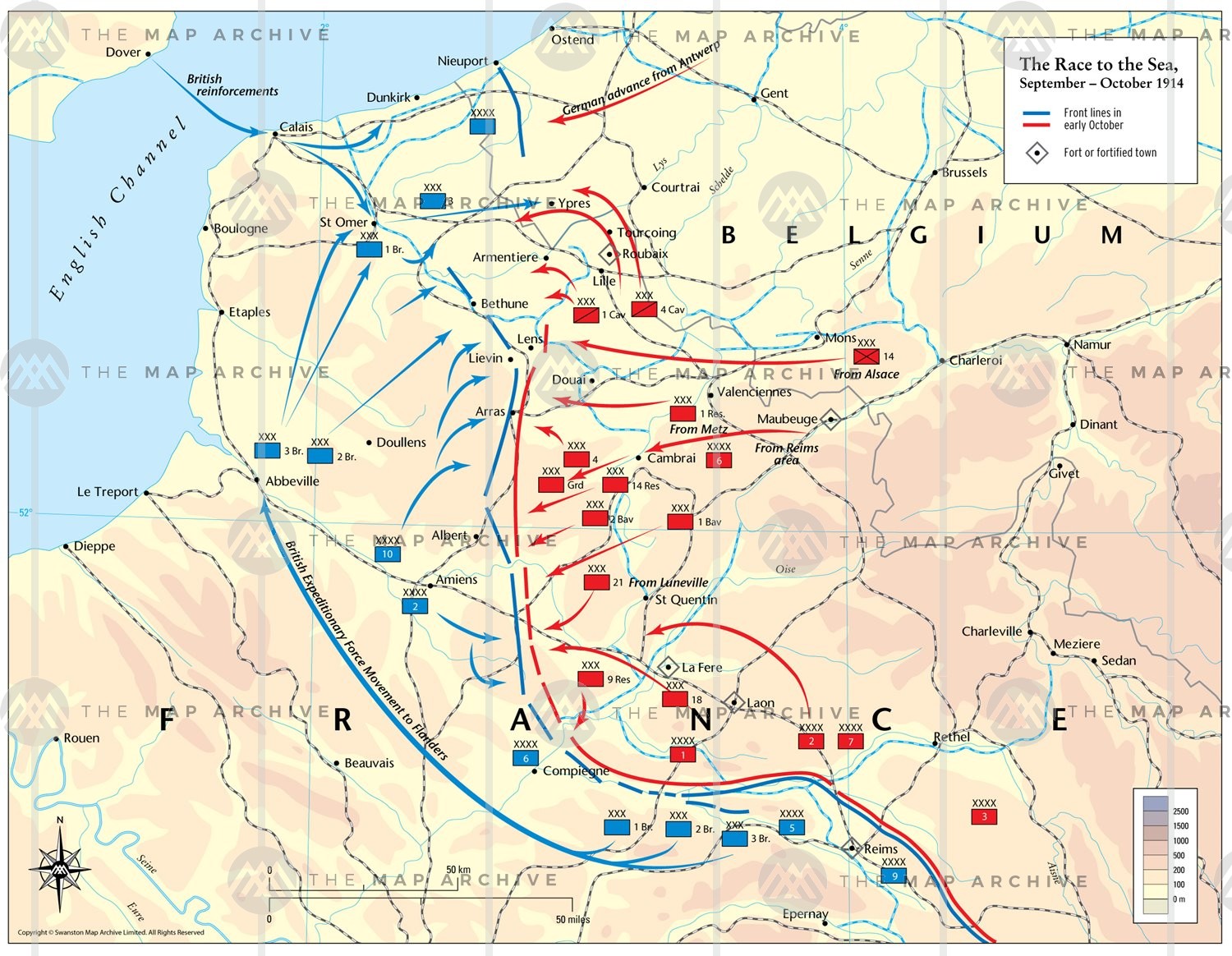

September, with Antwerp still holding out, the BEF, some 300,000 strong, fully

equipped, its reservists fighting fit, and with the RFC to direct its advance,

could have launched a massive counter-stroke from Abbeville, a major rail

junction, east between Arras and Albert (or even more boldly, further north

between Arras and Lille), on a front of at least 30 miles – with strong

reserves and artillery, screened by the Cavalry Corps, with the Indian Cavalry

Corps ranging further north towards the high ground at Vimy.

With a simultaneous offensive by the French along the Aisne

– indeed, across the whole front, to fix the Germans in place so that they

could not further reinforce the right – all that Falkenhayn’s 1st, 2nd and 4th

Armies would have been able to do to avoid being enveloped would have been to

turn through 90 degrees to face west. But their pivot point would have had to

be somewhere that did not form too sharp an angle and therefore a dangerous

salient, and with Belgian forces perhaps making another sortie from Antwerp, it

is probable that this pivot point would have to have been Rheims, or even

Verdun. In any case, with the BEF pressing hard, and taking account of its own

extended lines of communication, in particular the railheads, there would not

have been the manoeuvre space for Kluck’s 1st Army to change direction through

90 degrees west of a line running north–south through Mons and Maubeuge. Had

Falkenhayn got intelligence of the move of the BEF to Abbeville he might have

made an orderly withdrawal from the Aisne to the Mons–Maubeuge line, dug in and

brought up heavy artillery to halt the BEF’s advance; but this in turn would

have given the BEF the option of avoiding making a direct attack and again

threatening to turn the German right flank – further north, between Mons and

Brussels. In the best case for the allies, with the Germans unable to find a

natural line on which to try to halt the BEF, and a renewed offensive by

Franchet d’Espèrey’s and Foch’s armies to threaten the 1st, 2nd and 4th Armies’

lines of communication, Falkenhayn would have had to pull back to the Meuse below

Namur. He would then have had to garrison the river with all the troops he

could find as allied strength built up on the Lower Meuse as far as Liège and

within closing distance of the Dutch border in the Maastricht corridor.

Supposing, then, that at that point the Germans had been

able to check further allied progress east – even perhaps, by a desperate

reverse-Schlieffen transfer of troops from East Prussia – the situation in the

west would have seen a strategic sea change. Joffre, to exploit, could now have

used the growing Russian strength on the Eastern Front to his advantage:

Falkenhayn would have been truly caught between two giant hammers. And with the

Germans now on the defensive, Joffre would have had the choice of where to

concentrate. With so catastrophic an end to the whole Schlieffen ‘plan’, it is

not impossible to imagine the Kaiser’s suing for terms.

However, on 4 September the Triple Entente powers had signed

a pact: ‘The British, French, and Russian Governments mutually engage not to

conclude peace separately during the present war. The three Governments agree

that when terms of peace come to be discussed, no one of the Allies will demand

conditions of peace without the previous agreement of each of the other

Allies.’ All could not go quiet on the Western Front unless the Germans ceased

fire on the Eastern.

It was ironic that, by this pact, the British were now in

effect pledged to the defeat of the Germans not just in France but in Russia

too – an object that would have been scarcely conceivable to the cabinet a week

before the war began. Of course, in December 1917 a new (Bolshevik) Russian

government would conclude a very separate peace, but that was not an option for

a nation with ‘honour’, the noun that had propelled Britain to war. It is

possible, therefore, to imagine the war entering 1915 with a return to the

Elder Moltke’s view of the two-front problem: stay on the defensive against

France, check the Russians by a paralysing stroke (another Tannenberg,

perhaps), and then turn westward to counter-attack when the inevitable allied

offensive came – the aim being, since outright victory was no longer possible,

to cripple both opponents and thereby bring about a favourable peace.

But the allies would have been in a vastly superior strategic

position to that in which they actually found themselves in 1915. The

possession of most of Belgium would have been significant in terms of the extra

men and materiel available. And the failure of Germany to achieve victory would

not have been lost on the neutrals. It was almost certainly impossible that

Britain could have avoided war with Turkey, but if it were possible in May 1915

to persuade Italy, who in August 1914 had been in alliance with Germany and

Austria, to enter the war on the allies’ side – as she did, against

Austria-Hungary on 23 May, and Germany on 28 August – it should also have been

possible to persuade the Dutch and the Danes to consider their position too.

The Dutch obligation to defend Belgian neutrality under the Treaty of London was

sufficiently vague to permit the application of diplomatic pressure, especially

once the Germans had been removed from the southern Dutch border. It seems

likely at least that some way would have been found to open the Scheldt to

allied shipping, and to close the ‘breathing line’ to Germany. The Danes were

in just as ambiguous a position, if for different reasons. They had no

connection with any treaty, only a pragmatic decision to make: which side would

win? Or rather, how might the peace terms work to their advantage? Their

neutrality was weighted towards Germany, but a Germany fighting defensively on

the Meuse would not have been the same as a Germany in possession of almost all

of Belgium and a large slice of northern France. There was Danish territory to

recover in Jutland, and although in the event the Treaty of Versailles would

restore a large part of Schleswig to Denmark (and, indeed, would have given her

all of it, and Holstein, had the Danes not feared German irredentism),

Copenhagen could not have counted on it. There was, again, room for the

diplomats to work.

At the very least the BEF counter-stroke, forcing the

Germans back into Belgium, perhaps as far as the Meuse, would have given the

allies far better ground on which to fight – and with a strong Belgian army,

and a much shorter front (and therefore more reserves). At the very best, an

offensive by British, French and Belgian armies on the Meuse in the spring of

1915, perhaps being allowed to use the Maastricht corridor, with Dutch–Danish

action directed against the Kiel Canal and Heligoland, could have ended the war

that summer.

That said, the German army’s (the German nation’s) visceral

ability to fight on, despite all logic, was formidable, as the rest of the war

demonstrated. However, the ground on which the allies fought need not have been

the same; and the war was not immutably programmed to run until November 1918.

At best the Dardanelles campaign to circumvent the deadlock on the Western

Front need not have been attempted. The 1916 Easter Rising in Ireland might not

have taken place, or at least might not have taken the same embittering course,

for Britain would not have appeared to be on the ropes (there was more than a

little opportunism in the IRA’s decision to ‘declare war’); and with some

sensible concession to home rule the Union might still today have been of Great

Britain and Ireland (always assuming, of course, that Ulster could have been

placated – a big ‘if’). Perhaps the greatest bounties, however, would have been

the failure of the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia before it even started, and a

Germany in which fascism did not take hold.

Is this all too fanciful?

Three decades on, in the summer of 1943, after he had been

exerting his indomitable will on the nation and its armed forces for three

years of war, Churchill startled a group of his close associates by remarking

that ‘whoever had been in power – Chamberlain, Churchill, Eden, anyone you

liked to mention – the military position would now be exactly the same. Wars

had their own rules, politicians didn’t alter them, the armies would be in the

same position to a mile.’ This ‘Tolstoyan summary’, as one of Churchill’s

biographers, Ronald Lewin, puts it, was surely ‘Winnie’ at his most perverse,

fuelled perhaps by a little brandy and post-Alamein relief, and masked by cigar

smoke – Winnie the soldier still, defiantly growling from some long-remembered

battlefield. He was forgetting, perhaps even conveniently, his own politician’s

part in the bloody fiasco of the Dardanelles and Gallipoli. For just as wars

have consequences, so do battles – which is why they are fought – and likewise

the operational plans which determine in large measure where and how those

battles are fought. And the principal assumptions on which plans are made are

primarily political, not military; hence Asquith’s assertion at the CID meeting

in August 1911 that ‘the expediency of sending a military force abroad or of

relying on naval means alone is a matter of policy which can only be determined

when the occasion arises by the Government of the day.’ The fact was, however,

that the politicians had lost control of military strategy (and in this, of

course, British politicians were not alone), their failure to show effective

interest allowing a momentum to develop in the staff conversations whose

outcome then became the strategy because once revealed, during the crisis,

there seemed to be no alternative.

By refusing to recognize what this implied – a decision

deferred indefinitely – and instead basing all its plans on the assumption of

simultaneous mobilization with the French and the incorporation of the BEF into

the deployment plans of the French general staff, the War Office failed both

the army and the country. Since the War Office was both a department of state

and a military headquarters, this was both a political and a military failure –

and, since the secretary of state for war was a member of the cabinet,

ultimately a failure of cabinet government.

However the war began – by German design, by the negligence

of statesmen, by the purblindness of generals – there was nothing inevitable

about its course. Churchill said memorably, before the great clash of

dreadnoughts at Jutland in 1916, that the Royal Navy – in particular the

admiral commanding the Grand Fleet, Sir John Jellicoe – could lose the war in

an afternoon. In August 1914, however, the decisive ground was not the North

Sea but the Franco-Belgian border. And though government and the War Office may

have failed them, the men of the BEF, the ‘Old Contemptibles’, paid the price

of honour on that decisive ground, and paid it scarcely flinching – in honour,

as they had been variously exhorted, of the King, the nation, the British army,

or the regiment. They fought what they knew was the good fight because, as Sir

John French had told them, ‘Our cause is just.’ And despite the shortcomings in

planning and preparation over the years, the pride and prejudice in the senior

echelons as the nation went to war, and the mistakes by commanders and staff in

the first encounter battles, they fought a good fight – because, when all else

is going wrong, that is what professionals did (and do).

These, in the day when

heaven was falling,

The hour when earth’s

foundations fled,

Followed their

mercenary calling

And took their wages

and are dead.

Their shoulders held

the sky suspended;

They stood, and

earth’s foundations stay;

What God abandoned,

these defended,

And saved the sum of

things for pay.

Further Reading

Farrar-Hockley, Anthony. Death of an Army. New York: Morrow,

1968.

Herwig, Holger H. The First World War: Germany and

Austria-Hungary, 1914–1918. New York: Arnold, 1997.

Neiberg, Michael S. The Western Front, 1914–1916. London:

Amber, 2012.

Strachan, Hew. The First World War, Vol. 1, To Arms. Oxford:

Oxford University Press, 2001.