The Republican period ran from a traditional start date

established after the last King of Rome in 509BC and ended after Caesar was

assassinated and Augustus became supreme ruler in 31BC. Detailed archaeological

and historical evidence for this period of Roman military history is somewhat

elusive, but we do have three authors who provide us with some evidence of the

structure and behaviour of the early Roman army: Livy, Polybius and, of course,

Caesar himself. Their descriptions are good as far as they go, but provide us

with only a narrow view of the army of the late Republic. The authors,

excepting Caesar, do not provide a contemporary view of Caesar’s army and tend

to focus only on an idealized image of the legions, with little or no attention

given to other units such as allies or mercenaries. The case is not much better

with regard to the archaeological evidence. Here we can find some suitable

contemporary evidence for the Roman army of the late Republic, but it is

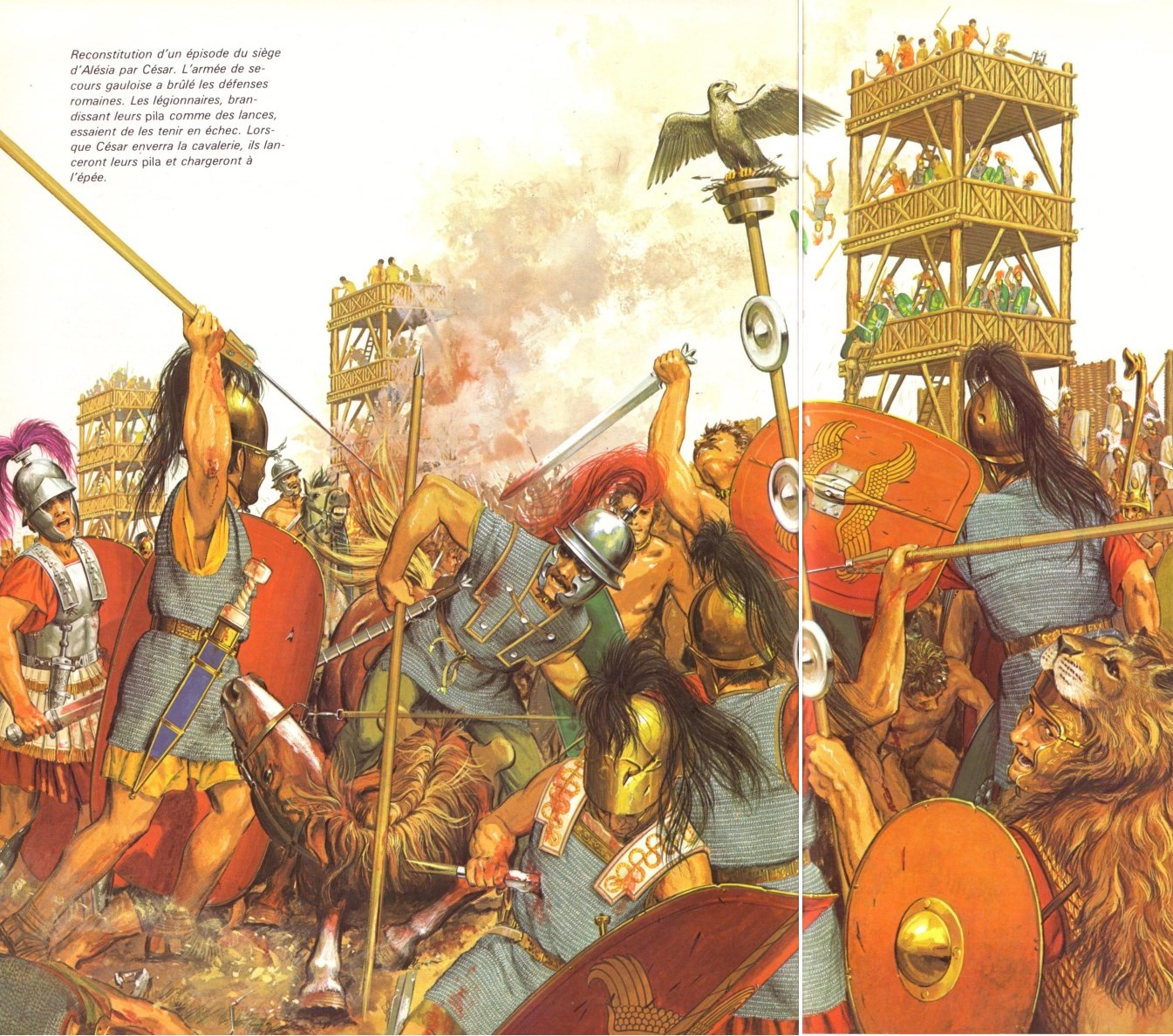

extremely limited, focusing on a few camps in Spain and naturally Alesia.

Unfortunately, as most of this data was unearthed over a century ago, even this

evidence is patchy. Our understanding of Caesar’s army, therefore, is built

from a mix of contemporary and not so contemporary sources, scholarly research

and debate.

Clearly Caesar’s legions did not simply spring to life fully

formed. While they were raised as complete units, this arrangement came about

as part of an inherited system of behaviour. To understand the character of the

Caesarean legion it is worth taking a brief look at how the legions developed

from their foundation. In reviewing the development of the legion as a whole,

some of the relationships between Gaul and Rome will become apparent. The

legion, as we understand it, was the consequence of a long period of changes

absorbed in the wake of military defeat. Although the Roman legion is now seen

as the epitome of military genius, the reality was somewhat different; in fact,

Rome’s success as a military power seems to have been due more to its ability

to learn from its mistakes. Rome’s brilliance was that it could accept its

weaknesses and adopt the successful elements of its enemies, whilst all the

time placing these within a structured military system. In due course, the

legion developed from the propertied man’s annual obligation to fight to

protect his land during the summer months, to the requirement for all males to

fight lengthy warfare for a campaigning season (usually March to October) and

finally to professional soldiers paid to fight constantly over prolonged

periods of many years. This transformation was concurrent with the expansion of

Roman territory and the change from the protection of the local community to

the requirements for a standing army to protect a vast and diverse Empire.

The armies of early Italy were little more than war-bands of

infantry and cavalry, raised by local tribes or princes when required, and

fighting when the seasons allowed. Charismatic and powerful men led these

bands, the best of which could provide protection for the individual and an

opportunity for advancement. It could be argued that these traits were

enshrined in the system from this early date, as the patronage of wealthy and

powerful leaders can be seen in the armies of Rome throughout its history.

Caesar was certainly a general who instilled in his legions personal devotion

to him. Finally, the early system of ad hoc recruitment became more

standardized, in order to provide a more regular and predictable turnout of

men. The first Roman armies consisted of around 3,000 men and were organized on

the basis of tribal groups, called a legio or a ‘levying’. Each tribe

contributed 100 men towards the total force – the origin of the ‘century’ of

Caesar’s legion. The wealthy elites in the tribe were relied upon to supply the

cavalry for the army, as only they could afford expensive equipment and horses.

This group, the equites or knights, survived as a social group long after their

original function had vanished, serving as officers in Caesar’s army. In

essence these early armies fought in similar ways to most early European armies

of the period. Warrior bands would fight under the command of their local

leader in unstructured groupings, while commanders would range around the

battle, urging them on to fight and selecting suitable enemy leaders for

combat. It is interesting to consider that the Gallic armies Caesar faced were

very much on a par with these early Roman armies.

After the Roman Republic began in 509BC, the Roman army

became far more formalized, along the hierarchical lines society was taking.

Greekstyle Hoplite warfare was the most advanced military tradition at the time

and represented a significant advancement on earlier military tactics. In

Hoplite warfare, troops fought as a densely packed line of heavily armed

spearmen. Cohesion was the key to this style of fighting and so the

hierarchical nature of Roman society was replicated in the legion. Only those

men with property were allowed to fight, giving the men a sense of duty and an

interest in preserving the State. It is worth noting here that Roman citizens

were providing the entire range of troop types in the army – a situation that

was not to last. As Rome expanded the areas coming under its domination, there

also came a necessity for an expanded army. The increased wealth of Rome meant

that the number of infantry and cavalry centuries could also be increased.

By the fourth century BC, Rome’s experiences of fighting

with the Latin and Gallic tribes had revealed serious weaknesses in the Hoplite

form of warfare. The more flexible fighting styles of the Gauls and Samnites

often highlighted the sluggish and formulaic nature of Hoplite warfare. To

counteract this problem the Romans began to adopt less dense formations, which

in turn required a revision of their tactics and equipment. The Roman phalanx

was reorganized into fighting formations called maniples – literally

‘handfuls’. The overall result was slowly changing the legions from the rigid

defensive formation of the phalanx into a cohesive collection of flexible

offensive fighting units. The fourth century BC saw the entire Italian

peninsula come under the control of Rome and as the sphere of influence

increased, so did the embracing of allied Italian peoples into the Roman army.

On campaign it became common for allied soldiers to comprise about the same

number of troops as the Roman legionaries. Armed like the legionaries, these

allied troops formed up either side of the legions in alae or wings. From this

time on, allied or mercenary units came to be a significant feature of the

Roman army.

‘On the expedition he

[Marius] carefully disciplined and trained his army whilst on their way, giving

them practice in long marches, and running of every sort, and compelling every

man to carry his own baggage and prepare his own victuals; insomuch that

thenceforward laborious soldiers, who did their work silently without

grumbling, had the name of Marius’ mules.’

[Plutarch, Lives of

the Noble Greeks and Romans, 13]

The turn of the first century BC saw a significant change in

the character of the Roman army. This has often been attributed to just one

man, Marius, but this may be somewhat overstated and simplistic.

Transformations had been taking place over the course of the previous three

centuries, therefore Marius’ role is most likely to have been as a catalyst for

the changes already developing. The army was now spending long periods away

from home and it was becoming a genuine career choice with the possibility of gaining

wealth and land from the proceeds of victory. Previously, the Roman army had

been an organized militia, galvanized with discipline and training.

Increasingly, the army was becoming more specialized and developing a core of

professional soldiers as Roman society became geared for on-going war.

Pragmatism was required in the face of the demands put on the army by the

ever-expanding areas of land to be controlled. This also resulted in a

relaxation of the prescribed requirements for entry to the army, which had

gradually been eroded almost as soon as the legion was developed. The

acceptance of elements of the non-land owning populace into the army had only

been done in extremis before, but now Marius attempted to increase the strength

of the army by changing the property requirements for service. He allowed the

recruitment of proletarii, the landless citizens of Rome, making the

class-based system redundant. The state had for some time been supplying

equipment to the army and so standardization was already occurring. Hence by

Marius’ time, the army was equipped fairly uniformly and the complex strata

exhibited in the previous system was removed. Thus Marius was unwittingly

responsible for homogenizing both the equipment and structure of the legions,

by allowing the process to become formalized.

In accepting the landless into the army, the State also had

to accept the responsibility of arming the legions, which, up until then, had

been paid for by the soldiers themselves. After their service these landless soldiers

were left to fend for themselves, so while they were in the legions they were

willing to follow any charismatic leader that promised them land afterwards.

Gradually, a subtle difference in the mind-set of the legions emerged, from a

landed militia protecting their own Roman lands, to a professional army

dominating annexed foreign provinces. Soldiers began to develop greater loyalty

to their generals, identifying with their leaders who, like them, sought

personal enrichment rather than seeing the maintenance of the structure of the

State as the purpose of their fighting. Individual grants of land and money,

distributed after military successes and service, were now becoming

commonplace. The politics of the late Republic were becoming ever more competitive,

hence in the struggle for advancement senators succumbed to more and more

aggressive policies and expansionist pressure. This was the world that Caesar

made his own.

Caesar leaves out much of the detail of his army because his

audience was well informed about the character of the Roman army of the period.

Caesar does tell us that he was using a system of cohorts, a simplified version

of the previous maniple system. Marius is thought to have been responsible for

the change from maniples to cohorts but it is likely that both systems could

have been in place together for a period. When Caesar set out on his Gallic

adventure in 58BC the cohort system was well established. Manipular legions

were made up of three distinct lines of formation, each one equipped

differently and socially differentiated. The cohort legion did away with these

equipment complexities, replacing them with a flexible body of similarly armed

men. It is likely that the system was introduced to deal with the difficult

nature of warfare in Spain. Tactics had to be developed to combat both the

Spanish guerrilla warfare and the mountainous character of the landscape. The

system retained the three-line formation, with a strengthened rear rank as a

reserve.

Caesar formed his legions for battle into what is called a

triplex acies formation, being four cohorts in front, with two lines of three

cohorts behind. This formation was something of a compromise between being wide

enough to form a broad frontage and deep enough to have reserves. The middle

cohorts provided the reserve for the front cohorts, while the rear cohorts

could be used for outflanking the enemy or if the legion was attacked in the

rear. The basic building blocks of the legion were the eighty-man centuries,

each one commanded by a centurion. Caesar depicts the centurions as the

fundamental glue of his legion, providing harsh discipline and motivational

inspiration in equal measures. Six of these centuries would provide a 400-man

cohort: this played the role of an individual tactical unit on the battlefield,

ten cohorts together forming the legion.

In the last century of the Roman Republic the command of the

army was removed from publicly elected consuls. Only after their period of

office could they command – a circumstance that had the effect of further

breaking the army’s connection to a citizenry. Caesar tells us that most of the

legions for his Gallic campaigns were raised during the winter months, when

campaigning had ceased. As governor of three provinces, he inherited the four legions

that were stationed in them and these could be augmented by further recruitment

from the provinces. Initially it seems that Caesar would raise the legion out

of his own money, then, after gaining acknowledgment of the unit from Rome, the

legion would become the responsibility of the State to maintain. Caesar

enlisted troops into the legions of both citizen and part-citizen ‘Latin’

status, thus continuing the process of blurring the qualifications for entry to

the legions. By collecting these diverse groups into unified legions, and by

exerting direct personal control over them, Caesar was able to place himself as

the main focus of the legion’s loyalties, before that of any other – even the

State. This meant that his forces were extremely loyal to him: a factor that

was to play its role in the subsequent Civil War (49–45BC).

The officers of the legions were not trained. In fact, most

received their posts as part of their political career. Six tribunes were

placed as middle-ranking officers of the legion and these were generally young

and untested men of aristocratic birth, often lacking in initiative or bravery.

Caesar chose the tribunes personally, many purely on the basis of political

expediency and patronage. Above the tribunes was a quaestor, a junior senator

who oversaw an entire province and provided Caesar with finances. Overall

control of a legion was placed in the hands of a legatus. Caesar chose a number

of legati; usually former tribunes, they were senators from a variety of

backgrounds and experiences, but were usually politically motivated choices.

Over the course of the Gallic Campaign, Caesar increased his

legions from the four he inherited, to twelve at the height of the fighting for

the Alesia Campaign. Thus, Caesar could have had up to 57,600 men at his

disposal. However, this number was only the paper strength of the legion, based

on around 4,800 men per legion. The actual number would, more likely, be half

this amount by the campaigning of late summer 52BC. Battle casualties,

infirmity, exhaustion and general wastage from the previous months’ campaigning

would all have played a part in reducing this tally to less than 30,000 men at

Alesia.

The 30 miles of fortifications – making up the

circumvallation and contravallation at Alesia – may seem very large, but when

one considers that its construction was divided among almost 30,000 available

men, each soldier would only have had to dig around 5 feet of trench and

rampart in the six weeks it took to prepare. In this light, the defences do not

seem such a superhuman task. In fact, when one considers that it was usual for

Roman legionaries to build a camp at the end of the day’s march, the building

of these fortifications seems well within the capabilities of the average

soldier. In truth, the greater task would have been the logistics of the

operation, including the planning, design, organization, supply and

implementation of the construction. However, this is where the Roman military

machine came into its own. If the defences at Alesia are exceptional, this is

only because the management of the army was exceptional and equal to the

Herculean task. Motivation to create such an engineering feat was an important

factor in Caesar’s army. Infantry training tended to focus on physical ability,

including running, jumping, marching and building – clearly necessary for the

construction work.

Increasingly, espirt de corps was also encouraged. The

legions began to be individualized by number and by name. Added to this,

individual legions were picked out by nicknames, often recognizing their

exploits, and by use of awards and honours on their banners and standards. This

is not to say that the legions were uncritically loyal to their leaders. While

the soldiers were made to give oaths of allegiance that imposed legal and

religious constraints on them, the Roman army was still prone to revolts and

indiscipline was common, mainly over pay or ill treatment. Often rewards would

be granted to keep the legionaries content. Caesar would often bestow on his

soldiers a promotion as part of the system of rewards, especially for

centurions. At Alesia Caesar’s handing over of slaves and booty to his soldiers

after the defeat of Vercingetorix is a clear example of this. To this was added

the spoils of war, along with donativa, one-off payments made by the general in

gratitude of service. After the Alesia Campaign, Caesar decided to double the

pay to ensure the loyalty of his soldiers for the coming civil wars.

The remaining archaeological evidence from Alesia is

confined to the siegeworks themselves. Roman weapons of the late Republic are

scarce throughout Europe, most coming from siege sites in Spain. At Alesia

there is surprisingly little in the way of Roman military equipment and this is

likely to be due in part to biases in the excavation of material. In the main,

archaeologists have focused their attentions on understanding the form of the

Roman defences. This means the results have concentrated upon the character of

ditches that bordered the Roman circumvallation and contravallation. These, it

has been discovered, were filled with javelins and arrowheads, which make up

the predominant proportion of the total weapons discovered at Alesia. While

some Roman pila (the legionary’s offensive missile) have been found, most of

the other weapons are likely to be Gallic in origin. If one considers that the

ramparts were mainly the focus of incoming missiles from the Gallic army, then

outgoing Roman missiles would have been fired into areas further from the

ramparts, where little or no excavation has been undertaken. Similarly, all the

swords so far discovered seem to be of Gallic origin, and again this may not be

unusual, as Roman weapons would have been retrieved after the battle had

finished to be used in future campaigns, whereas Gallic ones would only have

been recovered if they were considered valuable.

‘Gaius Sulpicius …

commanded those who were in the front line to discharge their javelins, and

immediately crouch low; then the second, third, and fourth lines to discharge

theirs, each crouching in turn so that they should not be struck by the spears

thrown from the rear; then when the last line had hurled their javelins, all

were to rush forward suddenly with a shout and join battle at close quarters.

The hurling of so many missiles, followed by an immediate charge, would throw

the enemy into confusion.’

[Appian, History of

Rome: Gallic Wars, 1]

Archaeological evidence shows that the panoply of equipment

of the Roman soldier differed only in detail from that of the better-equipped

Gallic warriors – sword, long shield, helmet, mail armour and spear.

Nevertheless, their appearance was different enough for one soldier to comment

that soldiers in the distance were not Roman because of their ‘Gallic weapons

and crests’. The Romans’ equipment wasn’t the only thing that was different

from the Gauls; their fighting techniques varied too. After throwing their

pila, the legionaries would engage the enemy adopting a crouching stance and

using a juxtaposition of punches with the shield boss and stabs with a sword.

It is evident from sculptural and archaeological evidence that the majority of

Roman legionaries were equipped to fight in this style, with heavy armour and

equipment. A large number of weapons have been found at Alesia, almost 400 in total,

140 of which are either javelins or spears. Unfortunately, these could be

either of Roman, Gallic or German origin. Some of the spearheads must be Roman

but it is unclear which, as leaf-shaped spearheads were a common form used

across Europe at the time. However, using other sources of evidence, we can

piece together a picture of Caesar’s legionaries. In the late Republic the

average legionary would have a decorative tall bronze helmet with a short neck

guard and large cheek pieces, a derivative of Gallic styles. The form was

called ‘Montefortino type’ and was sometimes enhanced with horsehair or feather

trappings. These decorative helmets were beginning to be replaced by a more

easily produced, plain style of helmet called a ‘Coolus’ or ‘Buggenum-type’ helmet.

It is likely that both types were in use at Alesia. In general, legionaries

would wear a mail coat that reached nearly to the knees, which was hitched up

with a military belt. Some sculptures suggest that these coats could have

further mail reinforcing on the shoulders. Pieces of chest fastenings from

these mail coats have been found at Alesia. However, as the Gauls were the

inventors of this form of defensive equipment, defining whether these fittings

are Gallic or Roman is very difficult. All legionaries would also carry a long

curved wooden shield, strengthened by a vertical central spine and which had a

small bronze boss covering the handgrip. On a legionary’s belt there would have

been a stabbing sword on the right hip and a long dagger on the left. Both

these weapons seem to be copied from types common in Spain.

‘[Caesar’s] …

soldiers, hurling their javelins from the higher ground, easily broke the

enemy’s phalanx. That being dispersed, they made a charge on them with drawn

swords. It was a great hindrance to the Gauls in fighting, that, when several

of their shields had been by one stroke of the pila pierced through and pinned

fast together, as the point of the iron had bent itself, they could neither

pluck it out, nor, with their left hand entangled, fight with sufficient ease;

so that many, after having long tossed their arm about, chose rather to cast

away the shield from their hand, and to fight with their person unprotected.’

[Caesar, The Gallic

War, I. 25]

The one piece of the legionary’s equipment that can be

directly attributed to Roman invention was his primary offensive weapon, the

pilum. Pila were a form of spear with a long thin metal shaft and a small

pointed head. Although pila are a Roman invention, examples of similar types of

weapons were also developed in Gallic and German contexts. Among the huge

number of missile weapons found at Alesia, pila are the predominant Roman

weapons evident. Up until recently, only fragments of pila were discovered,

mainly coming from the foot of Mont Réa. But in 1991 a complete example of a

Roman pilum was discovered in Fort Eleven. The examples from Alesia are

characterized by long thin shanks and points that come in pyramidal,

leaf-shaped or lance-shaped forms. There are different ways in which pila were

connected to the wooden shaft: some were connected by a socket that fitted over

the shaft and was riveted to it; other pila shafts had a wide tongue that was

sandwiched between the shaft and riveted in place. A final type had a pointed

tang that was driven into the shaft and secured by a collar. Usually, a round

shaft was used for the socketed and collared pila, whereas a square shaft was

used for the tongued versions. It is likely that the socketed pilum was lighter

than the tanged pilum, this is because the tanged pilum was often weighted to

provide extra penetration on impact. After his excavations at Alesia, Napoleon

III had replica pila made and tested. The results showed that the reconstructed

examples could be launched 30m and penetrate wood 3cm thick. Heavier pila were

weighted with lead and could have been thrown up to 70m. It is likely,

therefore, that pila were thrown at the Gauls before they entered the defences

of the circumvallation and contravallation at Alesia.

The equipment available for use by the legionary was

extensive and the legionary himself carried much of it. The requirement that

legionaries carry all their equipment is attributed to Marius: hence the term

‘Marius’ mules’, although the likelihood is that this is a misattribution. The

soldiers had always been required to carry their equipment, a regulation that

was regularly flouted. It is likely that Marius simply reinforced a standing

regulation in an attempt to make the soldiers more self-reliant and less

reliant on a baggage train – part of creating a professional army. Vegetius

suggests up to 60 pounds of equipment should be carried during training and

Josephus claims each soldier carried a saw, a basket, an axe, a pick, a strap,

a billhook, a length of chain and three days’ rations. The rest of a soldier’s

equipment, his tents and so on, were carried with the baggage. Along with this

equipment, the Roman army took with it large numbers of servants and slaves,

who were usually not armed but had sufficient knowledge of tactics to be of

use. Sometimes these groups were added to the regular army to give the

impression of a larger force than was actually available, such as at Gergovia,

where they were mounted on horses to look like cavalry. Merchants and camp

followers would also be part of the train, providing services that would

otherwise be unattainable in foreign countries. Large numbers of followers and

baggage had the tendency to slow the column on marches and so attempts were

made to reduce these numbers. One way of reducing the reliance on camp

followers was the local requisition of supplies and the creation of storage

bases along the route of march. In Gaul, where Vercingetorix had instigated a

scorched earth policy, this was impossible to maintain and so it is likely

Caesar had more followers than he would have wished to have.

The legions also took on campaign with them numbers of artillery pieces. These could be used aggressively, either in open battles and sieges to provide preparatory fire, or defensively to protect camps and siegeworks. Roman artillery comprised various sizes of ballista (sometimes called a catapulta or catapult). The ballista was a torsion catapult that used two twisted skeins of hair or tendons to provide energy for a string that fired projectiles. The ballista was built in various sizes that fired anything from small crossbow-sized bolts to large cannonball-sized stones. Parts of ballistae occur occasionally on archaeological sites. At Alesia three bolt heads were discovered, betraying the presence of ballista there. Ballista would allow Caesar to cover most of the regions outside his defences with a combination of fire from the hills surrounding the defences and the ramparts of the circumvallation. The larger engines were probably fixed in place once built and reserved for siege work, whereas the smaller artillery was often broken down and moved on pack mules, but could also be erected on carts or wheels (carroballista) to make them mobile on the battlefield.

Caesar´s Germanic Cavalry

Caesar’s Allies

‘It was the practice

of the Romans to make foreign friends of any people for whom they wanted to

intervene on the score of friendship, without being obliged to defend them as

allies.’

[Appian, History of

Rome: Gallic Wars]

Throughout the Republican period, Rome relied heavily on its

allies for additional infantry and cavalry forces to make up for a lack of

manpower. In some cases these were specialist fighters recruited on an ad hoc

basis and in varying strengths from the locality. More important were the

allied light troops who were drawn from Mediterranean regions Rome had long

been in contact with and with whom they had the closest relations. These troops

were customarily raised for the duration of a campaign, which sometimes led the

Romans themselves to questions their allies’ quality and commitment. Allied

formations were usually under the control of an individual unit’s chief, and

were armed, equipped and fought in the particular unit’s traditional style.

Usually the allied contingent of the Roman army was of equal

or larger size than the legionary force and was usually formed along Roman

lines. Units regularly seem to have been about 500 or 1,000 strong and broken

down into either six or ten centuries. These could be arraigned with the main

army in the centre of the Roman line or placed on both wings. Sometimes the

more lightly armoured allied contingents were mixed with the heavier armed

legionaries to prevent the allies from being picked off. Along with the heavily

armed troops, many of the allies provided specialist light infantry troops,

such as archers and slingers. These units are likely to have been dressed

according to their ethnic origin, although there is no definitive evidence of

which units were at Alesia. Over forty arrowheads have been recovered from

Alesia and it is thought that some of the Roman forms of arrows with one and

two barbs are likely to have been used by allied Roman troops. Roman arrows

were manufactured from iron and were up to 7.8cm long and 2.5cm wide. Tests of

reconstructed bows suggest they would have had a maximum range of around 300m,

and so they would be able to fire at the Gauls beyond even the deepest of

Caesar’s defences. Slings were also used and a number of examples of slingshot

come from Alesia, most notably three with inscriptions on them. Reconstructed

slingshots have shown a range of up to 400m, easily enough to provide covering

fire from any of the hilltops around Alesia into the valleys below.

Throughout his campaigns in Gaul Caesar does not define the

constitution of his cavalry and so we cannot be certain about their number or

ethnicity. It is likely that at least some of the cavalry at Alesia were Roman.

At the beginning of the conflict, Caesar was also able to call upon friendly

Gallic tribes to provide him with Gallic cavalry and these were employed as

warriors, as well as scouts, guides, interpreters and messengers. However,

Caesar had always considered them unreliable, a belief which was confirmed once

Vercingetorix rebelled and Caesar lost the majority of his Gallic troops to his

rival. Some must have been retained however, if only in an intelligence role,

but by the beginning of the Alesia Campaign Caesar was forced to employ new

cavalry in the form of German mercenaries.

‘Caesar, as he

perceived that the enemy were superior in cavalry, and he himself could receive

no aid from The Province or Italy, while all communication was cut off, sends

across the Rhine into Germany to those states which he had subdued in the

preceding campaigns, and summons from them cavalry and the light-armed infantry,

who were accustomed to engage among them. On their arrival, as they were

mounted on unserviceable horses, he takes horses from the military tribunes and

the rest, nay, even from the Roman knights and veterans, and distributes them

among the Germans.’

[Caesar, The Gallic

War, VII. 65]

Caesar tells us that the bulk of the German mercenaries were

cavalrymen. Evidence for Germanic cavalry in the archaeological record at

Alesia is slight; this is partially because German weapons are hard to

distinguish due to their similarity with Gallic weapons. One shield boss with a

central projecting stud is almost certainly German, given its similarities to

later German bosses. Bones of horses coming from the ditches discovered at the

foot of Mont Réa have been identified as coming from a male horse of no more

than three years old. These bones may represent the well-bred young stallions

given to the German cavalry. If this is correct, the evidence would conform

well to the German cavalry attack on this region. Recent interpretation

suggests that these horse remains may have been deliberately buried in the

ditches, not simply to cover them up, but in a form of sacrificial burial. It

was the Gallic custom to bury sacrifices in the peripheral ditches of

sanctuaries. In Gallic eyes, the circumvallation ditch may have been associated

with the practice of ritual sacrifice in these periphery ditches after the

defeat.

‘There is not even any

great abundance of iron, as may be inferred from the character of their

weapons. Only a very few use swords or lances. The spears that they carry –

framea is the native word – have short and narrow heads, but are so sharp and

easy to handle, that the same weapon serves at need for close or distant

fighting.’

[Tacitus, Germania,

VI]

Along with the cavalry, the Germans are described as using

spearmen who mingled with the mounted troops. This tactic may explain the

successes of the German cavalry during the Alesia Campaign. Tacitus tells us

that German warriors were lightly armed, the cavalry often having only a spear

and shield. The infantry were armed in a similar manner, with the addition of a

number of small javelins. All the Germans were dressed lightly with few wearing

armour or helmets. Some even fought completely naked. In the main, German

warriors wore breeches and large cloaks that would be draped over their

shoulders in regional style. Their clothing was manufactured in simple colours

and patterns, the only ostentatious part of their dress being elaborate knotted

hairstyles. These varied from tribe to tribe and so identified each warrior as

the member of a particular clan, a practice that had continued for hundreds of

years.

‘[The Germans are] … a

people who excelled all others, even the largest men, in size; savage, the

bravest of the brave, despising death because they believe they shall live

hereafter, bearing heat and cold with equal patience, living on herbs in time

of scarcity, and their horses browsing on trees. It seems that they were

without patient endurance in their battles, and did not fight in a scientific

way or in any regular order, but with a sort of high spirit simply made an

onset like wild beasts, for which reason they were overcome by Roman science

and endurance.’

[Appian, History of

Rome, 3]

Caesar tells us that the River Rhine marks the border

between the Gallic peoples to the south and the Germans to the north. German

warriors were famed for their physique, size and fearlessness – attributes

which in Roman eyes made them appear as savages. Like the Gauls, the Romans had

a stereotype for the Germans, who were seen as brutish to the point of

indifference to death (a recurrent image even up until the present). As ever,

the reality was very different; the German peoples had as complex a society as

any other of the period. There were close affinities between Celtic peoples and

Germans, in art, religion and culture. An innate conservatism meant that German

tribes were slow to change and reduced access to resources seems to have meant

that their technologies were less advanced than in Gaul. What they lacked in

technology the Germans made up for in vigour. It was this trait that so

impressed Caesar in his brief excursion across the Rhine into Germany – a trait

that was to put to great use during the Alesia Campaign.