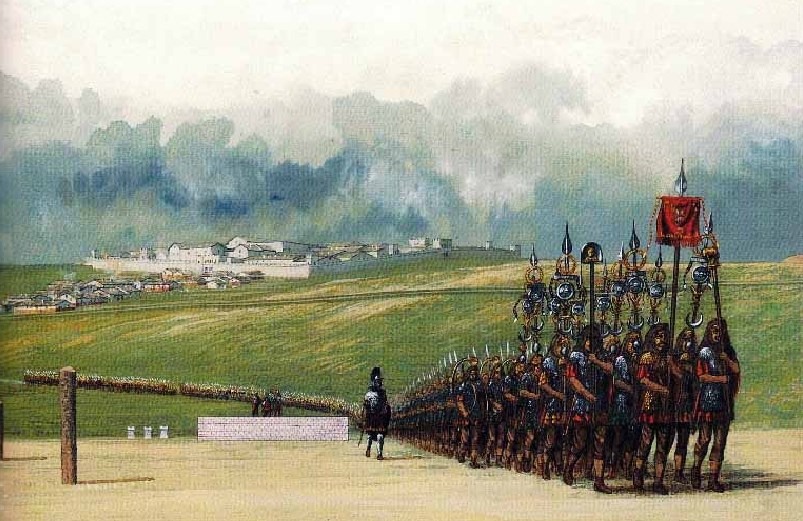

Fort at Vindolanda, AD 105. The fort housed the First Tungrian cohort

and a Batavian cohort.

The effects of imperial neglect can be seen on the British

frontier. The archaeological evidence from Scotland shows a lively

cross-frontier exchange in the first and early second centuries. Roman goods

found their way into native hands, from fine enameled brooches and sets of

bronze tableware to hinges and horseshoes. While the Votadini enjoyed a

profitable alliance with the Romans, deposits of mixed Roman and non-Roman

scrap metal at several sites indicate that local smiths were also doing jobs

for the Roman soldiers stationed on the frontier. Even some modest farmsteads

had access to Roman goods. During this period of strong cross-border ties, many

emperors devoted at least some of their energies to Britain, and the frontier

was briefly advanced into Scotland in the mid-second century. Starting around

160, however, the Marcomannic Wars took imperial attention away from Britain

for several decades. Despite some frontier shakeups under Commodus, it was not

until 208 that another emperor, Severus, took an active interest in the

province. Roman artifacts in Scotland show a corresponding decline after 160.

Even casual exchanges, such as Scottish crafters working for frontier soldiers,

seem to have dried up. While we might have expected provincial commanders to

take up the slack and maintain regional ties when an emperor was busy

elsewhere, the Scottish evidence suggests that they did not—or, more to the

point, they were not permitted to.

The Roman emperors’ relationship to the frontier was

contradictory. They could have enormous effects on frontier societies, whether

by leading their soldiers out on campaign or by pulling them back and assigning

them to border control. When an emperor turned his attention to a frontier

area, it must have been akin to an earthquake or flood: an unpredictable,

irresistible event that could change local conditions for generations, but

whose aftereffects were mostly left to the locals to deal with. When they turned

their attention elsewhere, their subordinates were limited in what they could

do to compensate for their neglect. Most of the empire’s frontiers, most of the

time, were left to themselves, shaped largely by the actions of the peoples who

lived along them.

The Army on the

Frontier

The most stable Roman presence on the frontier was the army.

While some frontiers were more fully militarized than others, all were marked

with fortresses and outposts where Roman soldiers were stationed to maintain

security and control. In regions with urbanized societies, such as Egypt and

Syria, the army’s influence was mostly limited to the hinterland zones. In

other areas, where local societies functioned on a smaller scale, such as

Britain and Arabia, the army’s effect on social and economic conditions was

more widespread. Across the Roman world, the peoples who lived at the fringes

of Roman power mostly knew Rome through its army, whose presence could be both

beneficial and disruptive.

Soldiers were usually well paid, since the emperors depended

on their loyalty. The regular provision of wages and supplies brought a steady

flow of cash and merchants into regions that in many cases had previously been

economically underdeveloped. The frontier army was a market for goods and

services from both inside and outside the empire. In the West, the pottery and

bronze industries of Gaul were stimulated by demand in the frontier regions.

The economic effect was less visible in the more developed East, but in

outlying regions such as the Egyptian oases, Roman forts provided a new market

for local goods. The reach of the frontier market extended well outside the

range of Roman authority. Peoples as far away as Himlingøje and Mecca increased

their leather and textile production to meet Roman demand.

The Roman army also offered employment to soldiers recruited

in and beyond the frontier zone. Barbarian auxiliaries were a vital part of the

Roman army for the same reasons that Greek mercenaries had been employed by

Egyptians and Persians: economically underdeveloped regions make prime

recruiting grounds for troops. After the revolt of Batavian soldiers serving

near their homeland in 69 CE, the Roman army began to station auxiliary units

away from the regions where they were recruited, so that future rebels would

not have the benefit of being surrounded by their own people. Once stationed in

their new locations, these units tended to recruit locally and lose their

original ethnic character over time, but troops were also relocated from one

part of the empire to another as military needs dictated. Because of this

reshuffling of personnel, we find, for example, a Pannonian soldier

commemorated with a funerary stela at Gordium in central Anatolia and offerings

to Syrian gods in the forts of Hadrian’s Wall in northern Britain. Some of

these soldiers married local women and started families, creating new

communities with ties to both the army and the local peoples. Their sons were

often recruited into the Roman army a generation later. Other auxiliary

veterans returned home across the frontier and played a role in mediating trade

and diplomatic connections between Romans and non-Romans. Recruitment from

beyond the frontier fostered the growth of a distinct military society that was

neither entirely Roman nor native to the lands in which it developed.

The Roman army could also be disruptive. The militarization

of the frontier interfered with traditional trade routes and seasonal movements

of laborers and pastoralists. Tacitus noted that unimpeded border crossing was

a privilege reserved for few, such as the friendly Hermunduri tribe:

For them alone among

the Germans is there trade not only on the [Danube] riverbank but even deep in

the most magnificent colony of the province of Raetia. They cross here and

there without guards and while to other people we show only our arms and forts,

to them we have opened our homes and estates.

The portoria, a customs duty of 25 percent, was collected on

all goods entering the empire’s eastern provinces. On other frontiers the rates

may have been lower, but there were still fees. The eastern trade routes could

be highly profitable: the record of a loan contract from Egypt documents a

cargo of perfumes, ivory, fabrics, and other luxuries from India in the second

century CE valued at more than 9 million sestertii. (For comparison’s sake, by

the late second century, a fortune of 20 million sestertii could put one in the

lower echelons of the imperial aristocracy.) High customs fees and valuable cargoes

encouraged smuggling. The Romans began to station customs enforcers in client

kingdoms beyond the frontier to help monitor the traffic.

Simply knowing what was going on along the frontier was a

challenge in itself. Surveillance posts and patrols were obtrusive shows of

force, but more subtle forms of spying are hinted at by the historian Ammianus

Marcellinus’ mention of the arcani, or “hidden ones”: “Their duty was, by

hastening far and near, to keep our generals informed of disturbances among nearby

tribes.” A fragmentary tablet from Vindolanda, a Roman fort in northern

Britain, with the text miles arcanus (“hidden soldier”) may relate to these

same spies, and another Vindolanda text possibly records a scrap of an

intelligence report on the locals’ fighting capabilities.

All this surveillance can only have been an aggravation to

those who lived along the frontier. Tacitus described a Germanic tribe

complaining that the Romans would not allow them to meet with their fellow

Germans who lived within the borders, “or else charge us a fee to meet unarmed,

practically naked, and under guard, which is even more insulting to men born to

arms.” The authority of frontier soldiers to stop, search, and tax travelers

was ripe for abuse. A merchant’s letter of complaint found at Vindolanda

suggests some of the misconduct soldiers indulged in. The beginning of the

letter is damaged, so the details are unclear, but it seems both the merchant

and his goods were threatened with violence, perhaps as part of a shakedown:

he beat me further

until I would either declare my goods worthless or else pour them

away. . . . I beg your mercy not to allow me, an innocent man

from abroad, about whose honesty you may inquire, to have been bloodied with

rods like a criminal.

The letter further details how the mistreated merchant had

appealed up the chain of command as far as the provincial governor with no

luck.

If a merchant who could write good Latin and knew how to

work the system got so little satisfaction for his grievances, the ordinary

people who lived in the outer shadow of Rome’s frontier cannot have fared much

better. With no effective recourse against exploitation, peoples of the

frontier zone resorted to raiding and revolt, such as the Frisians, who were required

to pay a tribute of oxhides to Rome, even though they lived beyond the Rhine.

In 28 CE the Roman centurion assigned to oversee the tribe demanded hides of

higher quality than the Frisians could supply. When their appeals for relief

brought no results, the Frisians revolted, killing more than a thousand Roman

troops before they were subdued.

Acting both as agents of imperial power and on their own

motivations, Roman soldiers made up one of the main forces at work on frontier

society, but Rome was not the only force along the frontier. Many other

peoples, cultures, and political forces, both those local to the frontier zone

and those farther away, interacted with Rome, pursuing their own agendas and

putting their own pressures on those who lived at the edges of Roman power.

Between Rome and a

Hard Place

A series of inscriptions from Volubilis in the foothills of

the Atlas Mountains on the Atlantic coast of North Africa records eleven

occasions over the first and second centuries CE when Roman officials held

negotiations with the Baquates, a collection of seminomadic tribes. To judge

from the inscriptions, the negotiations seem to have come to a satisfactory end

on each occasion. These inscriptions testify to the possibility of peaceful

coexistence among those who lived at the fringes of the Roman world, but the

fact that these negotiations had to be repeated over and over again also

indicates that, in the long term, frontier relations remained unstable.

What was true at Volubilis was true of the frontier as a

whole. While a tranquil coexistence was sometimes possible, and large-scale

hostilities were relatively rare in the empire’s first two and a half

centuries, the frontier was never quite settled. The disquiet of the frontier

arose partly from the nature of the societies along it, but also from the way

it was caught between worlds. The society of the frontier was constantly being

pushed and pulled by many different forces, both Roman and non-Roman. These

tensions were felt both inside and outside the demarcated boundaries of Roman

control. The conflict between different forces with different agendas

destabilized local societies.

Many of the peoples who lived in and around the Roman

frontiers are conventionally described as “tribes.” This vague word is applied

to various kinds of small-scale societies with no formal government that are

held together by networks of extended family ties and personal relationships.

Where Roman authors such as Caesar and Tacitus imagined stable ethnic groups

with names and defining traits, we should instead see most of the Roman

frontier zone inhabited by loose and changeable conglomerations of people who

were ready to form, dissolve, and re-form alliances as their interests shifted.

Trying to cope with these unstable groups was a challenge for the limited

resources of Roman foreign policy. The brutality in many of Rome’s interactions

with these peoples only sowed further disruption.

There were other societies at the edges of the Roman world

that were larger, more stable, and better able to deal with Rome on an equal

footing, including Kush, Parthia, and Himlingøje. For much of the first few

centuries of the Roman Empire, these peoples enjoyed relatively peaceful

relations with Rome. Their stability and organization made it easier for them

to pursue consistent long-term policies toward Rome and to rebuff Roman efforts

to meddle in their spheres of influence, but the existence of smaller, less

well organized states and peoples in between these major players also helped

stabilize relations. Kush had ongoing conflicts with the same desert raiders

that harassed the Roman southern frontier. Rome and Parthia managed to keep the

peace for more than a century in part because they were able to limit their

conflicts mostly to competition over influence in Armenia. Relations in the

North were helped because, during the Marcomannic Wars, the rulers of

Himlingøje were at war with the same peoples the Romans were fighting.

Caught in between these larger forces, the “tribal” peoples

of the frontier did what was necessary to survive. Sometimes they were able to

make a profitable peace with Rome and their other powerful neighbors. Sometimes

they were pushed into open war. Much of the time, they got by in a state of

uneasy cooperation, taking chances to profit from trade or military service

when they could get them, indulging in petty raiding and customs evasion when

they could get away with it, and suffering the abuses of bored soldiers when

they had to.

Good fences may make good neighbors, but what is good for

the neighbors is not always good for the fence. Earlier conceptions of the

Roman frontier often imagined the peoples just beyond the Roman borders as an

outer wall of client states, held in place by Roman diplomacy and intimidation

as a bulwark against uncertain threats from the unknown lands of the far

distance. When significant new threats to the security of Roman military and

political authority arose in the third century, however, they did not come from

the far-off reaches of Scandinavia or central Asia but from the frontier zone

itself. The peoples that Rome had been bribing, intimidating, patrolling, and

generally meddling with for centuries finally began to push back in more

effective ways. In the third century, peoples all around the edges of the Roman

world—in Scotland, Germany, the Black Sea steppes, Arabia, and North

Africa—began to succeed at what Arminius had attempted in the first decade CE:

to create large, stable alliances that could stand up to Roman power.