Jeb Stuart was an exuberant warrior and a great cavalryman,

whose magnificent exploits did much to promote the development of the cavalry’s

preeminence among the service branches of the Confederate army. He elevated the

cavalry raid to the status of an art, and, at his best, he carried out the more

traditional cavalry functions of reconnaissance and force screening more

effectively than any other cavalry commander on either side.

But the key phrase is at his best. Image and self-image were

important to Stuart—not just personally, but as the cornerstones of his

charisma and command presence—and these sometimes got in the way of his mission

objectives. At Gettysburg, this had the catastrophic effect of depriving Robert

E. Lee of critical reconnaissance and intelligence when they were needed most.

Part of the blame belongs to Lee, who wrote Stuart’s orders very poorly;

however, Stuart showed poor tactical and strategic judgment at the time of

Gettysburg and contributed to the defeat of the Army of Northern Virginia and,

ultimately, the demise of the Confederacy.

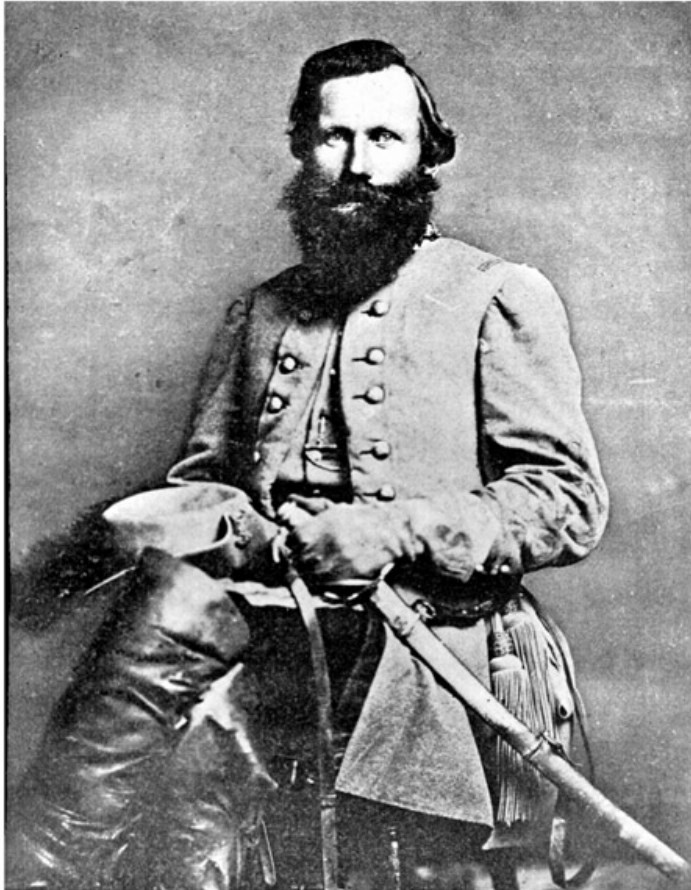

Among the icons of the Civil War is the warrior on

horseback, and no mounted warrior was and remains more gloriously iconic than

James Ewell Brown Stuart. He makes a highly appealing picture, arrayed in his

trademark scarlet-lined cloak and plumed cavalier hat, a red rose adorning his

broad lapel. Yet the reality of Jeb Stuart was far too complex to capture in

any iconic image.

Like Stuart, the cavalry itself is for many an emblem of the

Civil War. But the reality behind the role of cavalry in that conflict was,

like the reality of Stuart, more complex. Even the casual Civil War buff knows

that the Confederate cavalry was superior to that of the Union—at least until

Philip Sheridan’s Shenandoah Valley Campaign of August 7 to October 19,

1864—but the truth is that cavalry did not come easily to either side. In both

the North and the South, the first top commanders thought almost exclusively in

terms of infantry, artillery, and engineering. It was thanks largely to Jeb

Stuart that cavalry took root in the Confederate army at all, and its

development in that army owes much to the magnificent example he set.

Stuart made cavalry an indispensable branch for the

Confederacy. Therein lay his great contribution to the Southern war effort, yet

also his greatest failing.

James Ewell Brown Stuart—known by his first three initials,

combined phonetically into the familiar “Jeb”—was born on February 6, 1833, at

Laurel Hill Farm, his family’s plantation in the Blue Ridge country of

Virginia, near the North Carolina line. Though not of the Tidewater, his was

nevertheless a distinguished family, his great-grandfather, Major Alexander

Stuart, having fought at the Battle of Guilford Court House during the American

Revolution and his father, Archibald, having served in the War of 1812.

Archibald Stuart went on to become a prominent attorney and politician, who

served in the Virginia General Assembly and, briefly, in the U.S. Congress.

Jeb Stuart received his early education from his mother, who

also imparted to him a strong belief in God and the Methodist religion. Her

lessons were supplemented by those of local tutors until the boy was twelve

years old, when he was sent off to school at Wytheville, Virginia, then to

Danville, where he was tutored by his paternal aunt. In 1848, at fifteen, he

gained admission to Emory & Henry College after being turned down for

enlistment in the U.S. Army because he was too young. He did reasonably well in

college but acquired a reputation for fighting, always over some issue of

honor, whether actual or perceived.

Honor, of course, was not Stuart’s idiosyncrasy. His world

revolved around it. When his father failed to win reelection to Congress in

1848, young Stuart assumed that any chance of his getting nominated to West

Point—for the fighting lad still wanted to be a soldier—had evaporated. Yet,

not entirely to his surprise, the man who had defeated the senior Stuart,

Representative Thomas Hamlet Averett, nominated Jeb in 1850. The gesture,

gracious as it was, was also simply the honorable thing to do.

Stuart thrived at the academy, where he was very popular.

His best friends became Fitzhugh and George Washington Custis Lee, respectively

the nephew and son of Robert E. Lee, who was appointed superintendent of West

Point in 1852. Soon, Jeb Stuart became an intimate of the entire Lee family. He

graduated with the Class of 1854, standing thirteenth out of forty-six. He

achieved the rank of second captain of the Corps and was named an honorary

cavalry officer because of his easy expertise in the saddle. Legend has it

that, as he approached his final year, Stuart felt himself in danger of

excelling so highly in academics that he would be pushed into the Corps of

Engineers, which he considered a dull assignment. In truth, his

grades—especially in engineering—were simply not good enough to have admitted

him into the engineers, even if he had wanted such an appointment. Instead, he

was commissioned on graduation a brevet second lieutenant in the United States

Mounted Rifles, a cavalry unit based in Texas.

Stuart was assigned to Fort Davis in what is today Jeff

Davis County, Texas, and from the end of January 1855 through much of April he

led scouting missions along the San Antonio–El Paso Road. Late in the spring of

1855, he was transferred to the newly created 1st Cavalry Regiment at Fort

Leavenworth, Kansas Territory, where he served as regimental quartermaster and

commissary officer under Colonel Edwin V. “Bull” Sumner.

Promoted to first lieutenant soon after his transfer to Fort

Leavenworth, he also met that year Flora Cooke, whose father, Lieutenant

Colonel Philip St. George Cooke, commanded the 2nd U.S. Dragoon Regiment.

Within two months of meeting, Stuart and Flora were engaged, and on November 14

they were married.

While stationed at Fort Leavenworth, Stuart saw frequent

action pursuing and skirmishing with Indians and policing the guerrilla

violence between proslavery and antislavery factions in “Bleeding Kansas.” On

July 29, 1857, in a skirmish with Cheyenne raiders at Solomon River, Kansas,

Stuart was wounded in a saber charge. Scattering a party of Indians, Stuart

chased down one warrior, shooting him in the thigh with his cavalry pistol. The

Indian spun around and fired back with his own pistol. Although the round

struck Stuart full-on in the chest, the Indian’s weapon was old, and the wound

was superficial. Over the years, popular lore, however, inflated this incident,

portraying the wound as life-threatening and also suggesting that Stuart was in

command of a cavalry unit, which, though gravely injured, he led back to the

fort some two hundred miles away. In fact, Stuart was part of a detachment

personally led by Colonel Sumner.

Shortly after Flora Stuart gave birth to a daughter—also

named Flora—on November 14, 1857, Stuart was transferred to Fort Riley, where

he remained until the outbreak of the Civil War. In 1859, he devised a special

saber hook for fastening the cavalry saber to one’s belt. He received a patent

and secured a government contract to produce the hardware. While he was in

Washington, D.C., concluding the purchase agreement and pursuing an application

for a position in the army’s quartermaster department, Stuart volunteered to

serve as aide-de-camp to Colonel Robert E. Lee, who had just been ordered to

command a company of Washington-based marines and four companies of Maryland

militia to retake the U.S. Arsenal at Harpers Ferry, which the militant

abolitionist John Brown had seized.

At seven o’clock on the morning of October 18, Lee gave

Stuart the hazardous mission of riding to the Engine House, where Brown and his

band were holed up with his hostages, to deliver a surrender demand. Lee had

instructed Stuart to wave his cavalry hat if Brown (as expected) rejected the

demand. That would be the signal for the marines and militia to storm the

Engine House. Stuart carried out his assignment with calm deliberation,

delivered the message, turned from Brown, casually waved his hat, then deftly

stepped out of the line of attack and fire. The operation was over within three

minutes, and Brown, wounded by a deep saber blow to the back of his neck, was

in custody.

As civil war loomed, First Lieutenant Jeb Stuart had no need

to agonize, as many others did, over what side he would take. “I go with

Virginia” is how he explained his intentions should his native state secede.

The state seceded on April 17, 1861, but Stuart nevertheless accepted his

promotion to U.S. Army captain on April 22. It was not until May 3 that he

resigned his commission to join the Provisional Army of the Confederate States.

That his own father-in-law, Lieutenant Colonel Philip St. George Cooke, chose

to remain loyal to the Union and the U.S. Army although he was likewise a

Virginian, gave Stuart no pause. On the subject of loyalty, he was an

absolutist, and he insisted on changing the name of his son, who had been born

on June 26, 1860, from Philip St. George Cooke Stuart to James Ewell Brown

Stuart Jr.

FIRST BATTLE OF BULL RUN, JULY 21, 1861

Commissioned a lieutenant colonel of Virginia Infantry in

the Confederate Army on May 10, 1861, Stuart reported to Colonel Thomas J.

Jackson, soon to become known as Stonewall Jackson, who was in command at

Harpers Ferry of what had been designated the Army of Shenandoah. Stuart

persuaded Jackson to overlook his designation as an infantry officer and allow

him instead to command the Shenandoah army’s cavalry companies. Jackson agreed,

and Stuart quickly consolidated these units into the 1st Virginia Cavalry

Regiment. Robert E. Lee approved, and Stuart was promoted to full colonel on

July 16, 1861. Thus Stuart had made himself instrumental in the very inception

of the Confederate cavalry, which, for most of the war, would prove to be the

preeminent mounted force on the continent.

Stuart led his cavalry in a mission to screen the advance of

the Army of Shenandoah (now under the command of Joseph E. Johnston) from

Winchester to Manassas during the First Battle of Bull Run. Once in the battle,

he led a spectacular saber charge against a regiment of New York Zouaves,

sending them into a panicked rout. Some witnesses believe that this was the

action that precipitated the general Union retreat. Johnston was full of praise

for Stuart’s action at First Bull Run, calling him “wonderfully endowed by

nature with the qualities necessary for an officer of light cavalry. Calm,

firm, active, and enterprising.” Stuart was rewarded with a promotion to

brigadier general on September 24, 1861, and given command of the cavalry

brigade for what became the Army of Northern Virginia.

THE “RIDE AROUND MCCLELLAN,” JUNE 12–JULY 15, 1862

In the spring of 1862, during Union general George B.

McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign targeting Richmond, Stuart led his cavalry in

rear-guard actions covering the withdrawal of the Army of Northern Virginia up

the peninsula in the face of McClellan’s advance. When Johnston was badly

wounded at the Battle of Seven Pines on June 1, Robert E. Lee was given command

of the army, which he instantly put on an offensive footing.

Lee tasked Stuart with making an intensive reconnaissance of

the right flank of McClellan’s Army of the Potomac to determine its

vulnerability to attack. At the head of 1,200 cavalry-men, Stuart rode out on

the morning of June 12, quickly concluded that the flank was indeed exposed,

then proceeded to “ride around” the entire Union army, a circumnavigation of

150 miles. He returned to Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia on July 15,

with 165 Union prisoners of war, 260 horses and mules, and a wealth of supplies

in tow. Not only did he deliver to Lee precisely the intelligence he needed, he

elevated Confederate morale while lowering that of the Union in inverse

proportion. McClellan, the vaunted “Young Napoleon,” was humiliated.

Chronically hesitant and unsure of himself, McClellan was even more profoundly

shaken by the “ride around.” On a more personal note, Stuart had the pleasure

of defeating the Army of the Potomac’s cavalry, which was commanded by none

other than his father-in-law, Colonel Cooke.

CATLETT’S STATION RAID, AUGUST 22, 1862

The “Ride around McClellan” earned Stuart promotion to major

general on July 25, 1862, his cavalry brigade was expanded to divisional

status, and he was personally elevated in the Confederate public eye to a

position roughly equal to that of Stonewall Jackson. His triumph, however, was

nearly doomed to a very short life.

On August 21, Stuart became the target of a Union raid in

retaliation for the “ride around.” Narrowly escaping capture, Stuart fled

without his trademark plumed hat and scarlet-lined cloak, which were eagerly

appropriated by the Federal raiding party. Not to be trifled with, Stuart

mounted a bigger raid the next day against Catlett’s Station, headquarters of

the commander of the newly created Army of Virginia, the insufferably pompous

Major General John Pope. Stuart purloined the general’s dress uniform, together

with a Union payroll, and Pope’s papers, which included intelligence concerning

reinforcements for the Army of Virginia. This material would prove invaluable

in the coming Second Battle of Bull Run. Always ready to twist the knife,

Stuart sent Pope a message: “You have my hat and plume. I have your best coat.

I have the honor to propose a cartel for the fair exchange of the prisoners.”

Resolutely humorless, Pope did not respond.

SECOND BATTLE OF BULL RUN, AUGUST 28–30, 1862

Stuart’s cavalry played three roles at the Second Battle of

Bull Run. It scouted out the route by which James Longstreet’s “wing” of the

divided Army of Northern Virginia delivered the smashing

twenty-five-thousand-man assault against Pope’s flank while the Union general’s

attention-was riveted on Jackson’s “wing.” The second role was acting as a

screen for Longstreet’s infantry assault while protecting his flank with

artillery batteries. Stuart’s third role in the battle was the pursuit of the

retreating Federals after Longstreet’s assault. His men captured three hundred

of Brigadier General John Buford’s cavalry brigade troopers. At Second Bull

Run, Stuart made more, and more effective, use of cavalry than perhaps in any

other battle of the Civil War.

MARYLAND INVASION AND BATTLE OF ANTIETAM, SEPTEMBER 17, 1862

When Lee followed up on his triumph at Second Bull Run by

invading Maryland in September 1862, Stuart’s cavalry screened the northward

advance of the Army of Northern Virginia. For the first time, however, Stuart

was guilty of a lapse in performing reconnaissance. During a full five days of

Lee’s invasion, Stuart rested his men and even threw a celebratory party for

Confederate sympathizers at Urbana, Maryland. Stuart seems to have lost his

“grip” on the strategic situation, which led to a Confederate defeat at the

Battle of South Mountain (September 14, 1862).

Hard on the heels of the South Mountain exchange came the

Battle of Antietam, in which Stuart used his horse artillery to attack the

Union flank just as McClellan began the opening attack of the battle. Stonewall

Jackson directed Stuart to lead his cavalry in a drive to turn the Union right

flank and rear, to expose it to a follow-up infantry attack from the West

Woods. Stuart launched probing attacks against the Union lines, but this time

his artillery barrages were more than answered by Union counterbattery fire. In

fact, Stuart’s probing attacks unleashed a massive reply, which actually

prevented Jackson from executing the turning movement and follow-up he had

planned. It was only McClellan’s inherent reluctance to follow through on his

own success that saved the Army of Northern Virginia from something approaching

annihilation.

THE CHAMBERSBURG RAID, OCTOBER 10, 1862

On October 10, 1862, Lee, having withdrawn into Virginia,

sent Stuart to demolish a railway bridge near Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, while

also performing reconnaissance on Federal troop dispositions in the area and

capturing civilian hostages to be used in exchange for certain Virginians being

held by the Union.

Stuart expanded his brief ambitiously, performing another

“ride around” of the Army of the Potomac, a cavalry dash of 120 miles performed

in less than sixty hours, extending from Leesburg, Virginia, to Chambersburg,

Pennsylvania, and back. Once again, the Union army suffered humiliation but

little of strategic advantage was gained by this ride, which brought both rider

and beast beyond the edge of exhaustion.

BATTLE OF FREDERICKSBURG, DECEMBER 11–15, 1862

At the end of October, McClellan commenced a desultory

pursuit of Lee. Stuart responded by screening the movements of Longstreet’s

corps, in the process clashing with Union cavalry as well as infantry in

skirmishes near Mountville and Aldie (October 28) and at Upperville (October

29). He was crushed on November 6, not by the forces of McClellan, but by a

telegram informing him that his daughter, Flora, had died three days earlier of

typhoid. She was not yet five years old.

Suppressing his grief, Stuart next performed extensive

reconnaissance that allowed Lee to plan the defense of Fredericksburg from the

high ground overlooking the town. This put Longstreet’s corps in a virtually

impregnable position when Ambrose Burnside, who had replaced McClellan as

commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, launched his disastrous frontal

assaults on December 13, 1862. During this phase of the battle, Stuart and his

cavalry operated to cover Stonewall Jackson’s flank at Hamilton’s Crossing. His

horse artillery was especially devastating against Burnside’s hapless charges.

BATTLE OF CHANCELLORSVILLE, APRIL 30–MAY 6, 1863

After Fredericksburg, Stuart conducted a major raid to

within a dozen miles of Washington, D.C., capturing a significant number of

Union prisoners of war and supplies and destroying railway track and a bridge.

Come spring 1863, he and his cavalry division were instrumental in Stonewall

Jackson’s great flanking march in the Battle of Chancellorsville. On May 1,

Stuart’s reconnaissance discovered that the right flank of the Army of the

Potomac (now under the command of Joseph Hooker) was exposed and vulnerable. On

May 2, Stuart’s cavalry led Jackson’s II Corps against that flank, thereby

routing the entire XI Corps. Stuart was leading the pursuit of the retreating

Federals when word caught up with him that Jackson and A. P. Hill, Jackson’s

senior division commander, had been seriously wounded and were out of action.

Although Brigadier General Robert E. Rodes was next in seniority among infantry

commanders, he passed command to Stuart, whose reputation among the soldiers of

II Corps was so high that Rodes believed the transition to Stuart at this

critical moment would be more successful.

The loss of Jackson and Hill was potentially devastating,

but Stuart performed well as an ad hoc infantry corps commander, following

through on the flanking attack with another assault against the Union right

flank on May 3. When Hill recovered sufficiently to return to duty on May 6,

Stuart relinquished command to him. General Lee would have been amply justified

in giving Stuart a full corps command, but he believed that his ability with

cavalry was too valuable an asset and so retained him in his position.

BATTLE OF BRANDY STATION, JUNE 9, 1863

On June 5, with Lee and a pair of his infantry corps camped

near Culpeper, Virginia, Stuart requested that the commanding general witness a

grand field review of his troops, some nine thousand cavalrymen and four

batteries of horse artillery, near Brandy Station. Lee agreed, but because he

was unable to attend the June 5 review, the display was repeated on June 8. When

the Southern press published stories decrying this waste of resources on vain

demonstrations, Lee ordered Stuart to cross the Rappahannock on June 9 to

conduct raids on advanced Union positions.

Taking note of the activity near Culpeper and Brandy Station,

Major General Joseph Hooker ordered the Army of the Potomac cavalry commander,

Major General Alfred Pleasonton, to attack Stuart’s cavalry. Stuart was caught

by surprise, and a spectacular ten-hour cavalry fight, the biggest of the war,

ensued. In the end, Pleasonton withdrew, thereby allowing Stuart to declare

victory, although he had gained nothing and had allowed himself to be

surprised. On balance, the Battle of Brandy Station hinted at Stuart’s

vulnerability to the growing spirit and competence of the Union cavalry. The

Southern press in particular took note, and Confederate morale suffered

accordingly.

STUART’S RIDE AT GETTYSBURG, JUNE 25–JULY 2, 1863

As Lee maneuvered to engage the Army of the Potomac in

Pennsylvania, Stuart was eager to repair the damage his reputation had suffered

as a result of Brandy Station. Lee ordered Stuart to perform reconnaissance and

make raids, judging (Lee wrote) “whether you can pass around [the Army of the

Potomac] without hindrance” and, in the process, doing to “them all the damage

you can.” He also instructed Stuart to guard the mountain passes and to screen

the right flank of Richard S. Ewell’s II Corps. Poorly written and even

self-contradictory, the orders left a great deal to Stuart’s interpretation and

discretion. He interpreted them to provide the widest latitude possible for a

third “ride around” the Army of the Potomac. In this, most military historians

fault Stuart for a lapse of judgment motivated by vainglory; others fault Lee’s

orders, which were framed more in the nature of suggestions than

straightforward directions. In truth, what happened next was a blend of

Stuart’s poor judgment and Lee’s command style.

Beginning on June 25, Stuart advanced well east of the Army

of the Potomac, doing much damage to railroads and terrorizing citizens in the

vicinity of Washington and Baltimore. Along the way, he found himself blocked

by Federal infantry columns and was compelled to move ever farther east.

Ultimately, he went so far out of his intended way that he not only failed to

make contact with Ewell, but he also remained out of communication with Lee

during the first two days of what had developed as the Battle of Gettysburg. In

the days leading up to the single most consequential battle of the Civil War,

the commander of the Army of Northern Virginia was effectively blind and deaf

while traversing enemy territory. It was a catastrophe of war-losing

proportions.

When Stuart arrived at Gettysburg late in the day on July 2,

Lee viewed the booty he brought with him—captured Union supply wagons that had

served only to slow him down yet more—with disgust. No one overheard what Lee

said to Stuart, except for “Well, general, you are here at last,” which Stuart

himself took as a sharp rebuke. With the failure of Pickett’s Charge on July 3,

all that was left for Stuart to do was to screen Lee’s retreat, which he did

with great vigor and heroism. His men were the last to cross the Potomac into

Virginia.

In the immediate aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg, Lee

was unambiguous in accepting full responsibility for the defeat. Others,

however, unwilling to believe in Lee’s fallibility, blamed it all on

Stuart—more precisely on Stuart’s absence—and, to a lesser extent, on James

Longstreet’s lack of aggression. A balanced analysis requires taking into

account Lee’s judgment and his poorly written orders as well as Stuart’s

judgment and his interpretation of those orders. Had Lee been more direct in

telling Stuart what he wanted or had Stuart more effectively prioritized his

objectives—setting reconnaissance above all else—the outcome at Gettysburg (or

wherever else in Pennsylvania the showdown battle might have been fought) could

well have been very different.

OVERLAND CAMPAIGN, MAY–JUNE 1864

The Battle of Gettysburg marked Lee’s irreversible shift

from an offensive posture to a defensive one. Stuart tangled with elements of

the Army of the Potomac during Grant’s Overland Campaign, the bloody advance

toward Richmond, but was forced to function mostly in bitter—though quite

effective—rear-guard actions, as Grant, even after suffering defeat, continued

his relentless advance.

At the Battle of the Wilderness (May 5–7, 1864), Stuart

suffered significant casualties inflicted by George Armstrong Custer’s Michigan

Brigade but was subsequently able to delay the main Federal infantry advance to

Spotsylvania Court House, giving Lee critical time to set up strong defensive

positions.

Sheridan used superior numbers and repeated assaults to break Stuart’s

first line.

Stuart’s wounding precipitated the collapse of the Confederate position

around Yellow Tavern.

BATTLE OF YELLOW TAVERN, MAY 11, 1864

Ulysses S. Grant had appointed Major General Philip Sheridan

commander of the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps, only to find that the

army’s commander, George Meade, continually argued with him over just how the

cavalry was to be used. Sheridan sought to claim an aggressive strategic role

for his command, while Meade wanted cavalry to perform the conventional

functions of screening and reconnaissance. When Sheridan impudently defied

Meade, asserting that he could concentrate his cavalry and whip Stuart once and

for all, the Army of the Potomac commander reported the conversation to General

Grant, seeking Grant’s support to threaten Sheridan with a charge of

insubordination. Instead, Grant replied that Sheridan “generally knows what he

is talking about,” and he instructed Meade to let him launch his operation

against Stuart.

Sheridan’s first move was against the Beaver Dam Station of

the Virginia Central Railroad. His troopers attacked a train transporting three

thousand Union prisoners and liberated them. They then destroyed a huge cargo

of rations and medical supplies Lee could ill afford to lose. Stuart,

desperate, sent some three thousand of his cavalry to attack Sheridan, who had

in his command nearly twelve thousand troopers.

On May 11, the forces clashed near an abandoned inn called

Yellow Tavern six miles north of Richmond. Despite Sheridan’s two-to-one

advantage over Stuart, it was a very close-run fight. After some three hours of

combat, the 1st Virginia Cavalry charged head-on into a Union advance, pushing

it back. Positioned on the top of a small hill, Stuart personally led the

battle. He could hardly have made himself a more conspicuous figure, and a

dismounted 5th Michigan Cavalry private, John A. Huff, a former sharpshooter,

saw him, recognized him, leveled his .44-caliber revolver at him, and fired.

The round entered Stuart’s left side, penetrating his

stomach before exiting his back. Few survived gut shots in the Civil War. Taken

to the home of Dr. Charles Brewer, his brother-in-law, Stuart lingered until

7:38 p.m. on May 12, the day after the battle. He died before his wife could

reach his bedside. Notified of Stuart’s death, Lee broke the news to his staff,

remarking, as if by way of epitaph, “He never brought me a piece of false

information.”