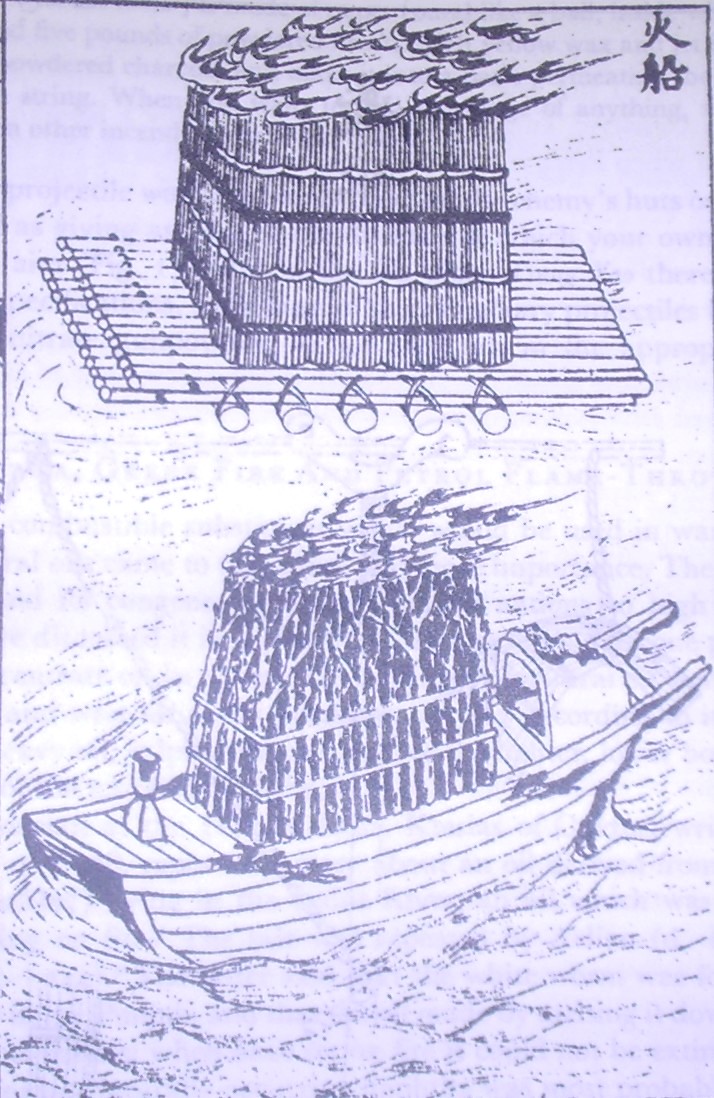

Chinese fire-rafts as illustrated in the Wujing Zongyao, a military

treatise written in 1044 during the Song Dynasty. This demonstrates the

antiquity of such devices.

An illustration of a fireship from a book written about 1553 by the

Chinese imperial official Li Chao-Hsiang, superintendent of the Dragon River

Shipyard near Nanking. The Chinese devoted a great deal of ingenuity into

making fireships look like ordinary warships. The main trick was to conceal the

boat in which the crew would make their escape. In the `mother-and-child’ boat

the escape-boat was completely concealed within the after part of the hull, and

appeared only when the victim had been rammed and set on fire. To make the

principle clearer, the escape-boat in the picture is more visible than it would

have been in reality. At the bow we see the `wolf’s-teeth nails’ which secured

the fireship to its victim.

The Chinese fireship represented here also derives from Li

Chao-Hsiang’s book about the Dragon River Shipyard. We can see it is a kind of

combination-vessel, with the fastenings amidships working on the hook-and-eye

principle. At the bow the `wolf’steeth nails’ were rammed into the opponent’s

hull, the rockets and fire-missiles which are to be seen in the forward part of

the hull were ignited, and the crew made their escape from aft. In this

arrangement, too, the escape-boat for the fireship crew was invisible.

Fireships were becoming increasingly popular in Europe by

the beginning of the seventeenth century. But these destructive inventions were

not limited to the West. Fireships were also used by the Imperial Chinese Navy

in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and their deployment and the

deception of the enemy that went with them formed a well-understood part of the

general Art of War.

In China, naval skirmishes occurred for the most part in

rivers or in the mouths of estuaries, rather than on the open sea, for in these

relatively calm waters it was possible to make use of favourable tides and

currents, which were ideal for fireships. There are even descriptions of

successful fireship attacks from Chinese antiquity, one example being the battle

of the Red Cliffs, fought on the Yangtze-Kiang in 208 AD. One side set alight a

large number of boats laden with brushwood and oil, and these `fireships’

caused such panic among the enemy ships that they were run aground on the banks,

with huge loss of life.

About 1553 there appeared a book written by Li Chao-Hsiang

(Li ZhaoXiang), the superintendent of a large and important installation near

Nanking called the Dragon River Shipyard. In this book, which is illustrated

with woodcuts, he discusses historic vessels and events, from which it is clear

that in China, just as in Europe, there were a number of specialised types of

ship, and men of seemingly limitless inventiveness. As regards fireships, for

the Chinese the most obvious problem was that of getting the ship within

striking distance of an enemy without raising his suspicions. This was not

regarded as purely a function of technology, but also a matter of psychology:

how to exploit the enemy’s wishes and expectations. For example, in the

fourteenth century (by the Western calendar), there was an incident in which

one of the warring parties managed to convince the other that some of its ships

intended to defect, and as a result they were allowed to come near – too near,

as it transpired, when it became clear that they were fireships and there was

no way to avoid them.

In his book, Li Chao-Hsiang discusses several technical

tricks from the Chinese Art of War that could be used to disguise a fireship. Prominent

among these were various methods developed by the shipbuilders of constructing

the hull in two parts, either in tandem or side by side. The original function

of these `two-part’ junks was to divide on reaching shallow water, since each

half drew less water than the whole ensemble. The fireship variation of the

principle was built so that one part of the vessel – the inflammable `business

end’, so to speak – could be made fast to the enemy, while the crew used the

other section to make their escape. The combination-vessel looked harmless

enough as it approached, because one sure sign of a fireship was missing: a

boat in tow, ready for the crew to make their escape. Li Chao-Hsiang described

it as follows:

A vessel of this type is about fourteen metres long, and

from a distance looks just like an ordinary ship. But in reality, there are two

parts to it, with the forward section making up about one third, and the after

part two thirds of the length. These are bound together with hooks and rings,

the forward part being loaded with explosives, smoke-bombs, stones and other

missiles, besides fire emitting toxic smoke. At the bow are dozens of barbed

nails with their sharp tips pointing forward; above this are several

blunderbusses, while the after part carries the crew and is equipped with oars.

Should wind and current be favourable when they meet an enemy vessel, they set

a collision course, ram the bow as hard as possible into the enemy’s bulwarks,

and at the same moment let go the fastenings between the two sections, and the

after part heads back to its base.

A variant of this vessel was the `mother-and-child boat’, a

perfectly camouflaged fireship about twelve metres in length. The forward part

was seven metres long and was built like a warship, while the after section,

5.25m long, consisted of a framework with what appeared from a distance to be

the sides of the vessel separated only by a scaffolding, which supported the

big balanced rudder and concealed the oar-propelled escape-boat. On either side

of the bow there were `wolf’s-teeth nails’ and sharp iron spikes to prevent

boarding. The attack was made by ramming the enemy ship, which was then held

fast with grapnels, and at the same time distracting the victim with a hail of

arrows, stones and other missiles. The vessel was loaded with reeds, firewood

and flax saturated with inflammable material and bound together with big

black-powder fuzes. Once it had been ignited and the enemy was on fire, the

daughter-boat was cut loose and the crew made their escape.

Europeans would encounter such weapons when their desire for

commercial expansion brought them into conflict with the Chinese. The

Portuguese first came to China about 1516, and by the following year an

ambassador had visited the Chinese capital and obtained permission for

merchants to establish themselves and transact business in the trading centre

of Canton. For a long time the Portuguese were the only foreigners with this

privilege, which they later tried to turn into a total monopoly of the export

trade in the waters of southern China on the basis of their military strength.

They expected to repeat the success they had enjoyed in India, but in 1521 and

1522 the Chinese decisively defeated them at sea, and when trade was resumed it

was on Chinese and not Portuguese terms. The merchants switched to smuggling,

and when the authorities found they could not stamp this out completely, in

1587 they permitted the Portuguese to set up a trading post on the island of

Macao, at the mouth of the Pearl river. This was the foundation for the

Portuguese monopoly of trade between China and Japan.

For decades the Portuguese suffered no competition from

other Europeans and made huge profits, but at the beginning of the seventeenth

century the first Dutch fleets began to poach upon the preserves of their

colonial empire. The sea power of the Dutch slowly increased after the

foundation of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in 1602; Molucca came under

their sway, and the town of Batavia was established on Java, on the Sunda

Strait. Apart from some minor setbacks, Dutch merchants enjoyed great success

in Asia, but they could not get a toehold in China. They failed to establish a

permanent trading post on the mainland, never winning the trust of Chinese high

officials. In the Middle Kingdom the `red barbarians’ were considered cunning

and greedy. The only notable thing about them was their powerful ships, with

their double-planking and `rigging like a spider’s web’.

In the year 1622 the Governor of the VOC in Batavia gathered

enough courage to take his fleet on an offensive against the Portuguese in

Macao, in an attempt to take over the China trade by force. However, the attack

was repulsed and the Dutch proceeded to the Pescadore Islands in the Formosa

Strait, where they began work on a fortified strong-point. At the same time they

tried to set up a permanent trading base in Amoy (Xiamen), but just as before,

their negotiations with the mandarins went nowhere, and they failed.

The Dutch now decided to use a trade war and a blockade to

force the Chinese government to trade with them. Thus in January 1623 a VOC

fleet raided the coasts of Fukien and Kwantung in south China, destroying the

huts of the farmers and reducing the trading junks in the little coastal ports

to ashes. This was a poverty-stricken part of the country, and the Chinese

military were powerless to stop them ashore. At sea, the navy could not stand

up to the heavily armed vessels of the Dutch, but there was one thing it could

do: attack with fireships. The fireship was the one Chinese weapon that

inspired fear in the Europeans.

As previously mentioned, Chinese fireships were normally

deployed in rivers and estuary mouths, for the most part disguised as fishing

boats, so the apparently innocent craft could drift down on the anchored

Indiamen at all hours. However, the Dutch learned to moor their ships with two

anchors, athwart the stream, so that if need be they could slip one, allowing

the ship to swing round and avoid the attacker. The crews were kept on the

alert, with the slow-match always burning and guns at the ready, so they could

engage quickly; any suspicious vessel would be immediately brought under fire

and sunk. Standing orders were nailed to the mainmast by the commandant of the

fleet, with stiff penalties for disobedience: anyone absent from his post, or

sleeping on watch, would be hauled up to the main yardarm and dropped into the

water three times for the first offence; a second offence attracted fifty

lashes; and if he further misbehaved, the ship’s council might decide it was a

capital matter, and he would be hanged.

The VOC’s war on the Chinese state did not have the desired

effect and, apart from gaining a seasonal trading permit which they had to

renew every year, the Dutch again failed to establish themselves on the

mainland. The strongpoint in the Pescadores had to be abandoned, and only in

1624, after building a fort and trading post on Formosa, did they gain indirect

access to the lucrative China trade.

It was not just the Dutch who had to face the Chinese

fireships. Among others who had to deal with them on the Pearl river were three

English East Indiamen under the command of Captain John Weddell. The English

ships were observed with hostility and suspicion by their competitors, the

Portuguese, as they sailed up the river, trying to get as close as possible to

Canton, the trading entrepot of the area. On board one of them was a remarkable

man, Peter Mundy, a traveller who had roamed all over Europe and Asia recording

his adventures and observations, and it is from his journal that we know what

happened on the Pearl river on the dark night of 10 September 1637.

The three ships, the Anne, the Catherine and the Dragon, lay

at anchor astern of one another, and at two in the morning the water was

flowing quickly, with the ebb-tide reinforcing the normal current. They were

expecting goods to arrive from Canton and did not think too much about it when

they saw some junks sailing towards them. The Anne, the smallest of the three,

lay furthest upstream, and at first it looked as if the junks were just going

to sail past, but then they altered course to bring themselves athwart the

hawse of the bigger Catherine. The alarm was raised and the junk was fired on,

alerting the other ships. The shot appeared to act as a signal to the junks,

which all at once burst into flames – they were fireships!

Immediately the English realised what was going on. The

first two fireships were connected by chains, and then three more appeared, all

steering for the English ships. However, they had no more time to observe, for

they had to work flat out if they were to save their lives. Luckily it was

almost the end of the ebb, and the current slackened somewhat, which gave them

time to cut or slip their cables and make sail. Even more fortunately, just at

that moment a light breeze sprang up, and having had the foresight to keep

their boats in the water, they were quickly able to take the ships in tow. `The

fire was vehement. Balls of wild fire, rockets and fire arrows flew thick as

they passed us, But God be praised, not one of us all was touched.’

The night was lit up by blinding flames, which illuminated

the hills above the river bank. And the noise as the fireships drifted by was

unnerving, the cries of the Chinese crews aboard them blending with the

crackling of burning bamboo and the whistling and hissing of rocket and

fireworks canisters. In the light of the flames, the English watched as the men

on the burning junks jumped into the water and swam for the shore. One of the

junks ran aground at the level of the Indiamen, while two more drifted out of

sight downstream, and one junk seemed to have been set on fire prematurely and

burned out harmlessly, before she reached the English ships. Now they awaited a

second attack while it was still dark, but after two hours the fireworks were

finally over.

When day broke the English looked on the river banks for

Chinese sailors who had abandoned the burning junks, but they found just one

swimmer, who attempted to evade them by diving. Finally he was hooked with a

pike and hauled aboard halfdead. Then behind an island they found the biggest

of the fire-junks, which was still intact, having run aground before being set

on fire. Peter Mundy learned about the appearance of this vessel from the crew

of the boat:

This being full off dry wood, sticks, heath, hay, etc, thick

interlaid with long small bags of gunpowder and other combustible stuff, also

cases and chests of fire-arrows dispersed here and there in abundance, being so

laid that might strike into ships’ hulls, masts, sails, etc, and to hang on

shrouds, tackling, etc, having fastened to them small pieces of crooked wire to

hitch and hang on any thing that should meet withal. Moreover, sundry booms on

each side with 2 or 3 grapnels at each with iron chains; other also that hung

down in the water to catch hold of cables, ground tackle, etc so that if they

had but come to touch a ship, it were almost impossible but they catch and hold

fast.

The English salvaged the grapnels and chains from the junk

and then set it alight. `It burnt awhile so furiously that it consumed the

grass on the side of the hill as far as a man could fling a stone; so that had

they come within as they came without us, they had endangered us and at least

driven us out.’

The Chinese sailor in the boat was patched up by the ship’s

surgeon and survived, and was put in irons. The English learned from him that

the fireship attack had been instigated by the Portuguese at Macao, and that the

intention had been to catch the ships just at change of tide, when they would

swing broadside to the stream and present a bigger target. Captain Weddell and

his men had been very lucky.