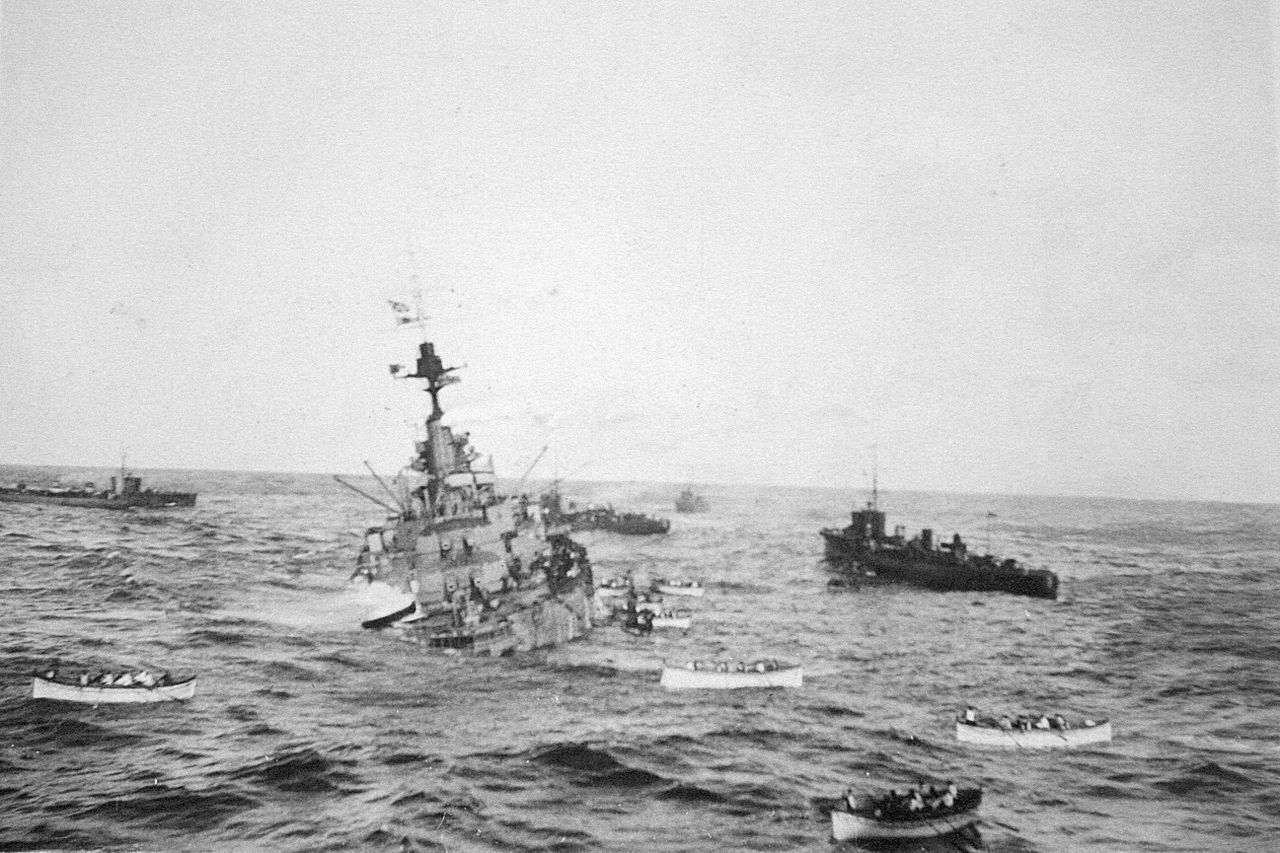

HMS Audacious crew take to lifeboats to be taken aboard RMS Olympic

By George P. Clark

The sinking of HMS Audacious has been described as the

greatest secret of the war. Manned by 1,000 picked officers and men, she was

Great Britain’s crack battleship and the pride of the British Navy. At

exercises and gunnery, and for smartness and cleanliness, she could not be

beaten, and for a ship to attain such a status as this in pre-war days was,

indeed, a tremendous achievement, for competition in the Fleet was keen, and

enthusiasm ran very high. It is, therefore, no wonder that when disaster befell

this great ship and brought about her total loss, the Admiralty took most

extraordinary precautions to keep the news from the Germans.

We, the officers and crew, were all sworn to silence, and

the British Press, by reason of an appeal from the Board of Admiralty to

suppress the news, had no alternative but to remain silent. But rumour soon

spread round the country until the story that ‘a whole battle squadron had been

sunk’ was being freely circulated. The true story did eventually reach Germany

through the medium of American newspapers, for during part of the time the ship

was struggling for her life, she was photographed by American passengers on

board the White Star liner Olympic, that was standing by.

We belonged to the 4th Battle Squadron comprising the

battleships King George V, Ajax, Centurion and Audacious, and which was under

the command of Admiral Warrender, whose flag, at the time of the disaster, was

flying in the Centurion. We had shared those cold, misty mornings in the autumn

of 1914 with the remainder of the Grand Fleet, steaming up and down the North

Sea waiting and watching for the German High Sea Fleet. But when the big action

was eventually fought between the two great fleets the Audacious was not there.

She, or her shattered hull, was safe in that part of the graveyard of Mr Davy

Jones which lies about 19 miles N ¼° E of Tory Island, off the north coast of

Ireland.

A short time before this disaster happened, the German High

Command had decided to mine the entrance to the mouth of the Clyde in order to

intercept, and, possible sink, a convoy of thirty-three troopships with

Canadian troops on board which was expected about that time. The German armed liner

Berlin, with Captain Pfundheller in command, was selected for this dangerous

and deadly work. The Berlin was, accordingly, loaded up with mines, and Captain

Pfundheller’s instructions were to lay them athwart the Glasgow approach

between Garroch Head and Fairland Head; or, in the event of this being

impossible, the principal change on, or south of, the line Garroch Head-Cumbrae

Lighthouse.

As early morning fogs are frequent on this part of the

Scottish coast in the autumn, the German captain was advised to arrive at his

destination at about 7.00am under the cover of such fog or mist as might be

present. And so, under conditions of the greatest secrecy, the Berlin sailed

from the Weser on 21 September 1914, with her cargo of death and

destruction-dealing mines. On his arrival at night in the vicinity of the Firth

of Clyde, after having been six days at sea, Captain Pfundheller, his ship

cleared for immediate action, was quite unable to fix his exact position by

cross-bearings as, of course, the flashing lights which help navigators in this

difficult part of the British Isles were not working. In these adverse

circumstances he found himself compelled to abandon his original intention and

decided instead to drop his mines in a position 19 miles N ¼° E. of Tory

Island. It was one of these mines which sank the Audacious.

It is interesting to note at this point that had the mines

been laid in the position originally intended they could not have damaged the

large convoy of Canadian troops as all these ships were, fortunately, diverted

to Plymouth where they arrived safely!

The 4th Battle Squadron put to sea in the morning watch of

27 October 1914, and, at about 8.45am, the Admiral made a signal ordering the

Squadron to alter course 4 points to starboard. We, the Audacious, were the

third ship in the line and were, I believe, a little out of station when we

came up to the actual turning point. We did not answer our helm as quickly as

might have been expected, and as we were swinging round to the new course in

the wake of the two ships ahead of us, there was a sudden dull explosion on the

port side aft, and obviously considerably below the waterline. The ship

immediately heeled over to port and the engine-room quickly flooded. Clouds of

steam and smoke burst from the after funnel and up the main hatches, and it was

feared that the men in the stokeholds and engineroom had suffered bad

casualties. They were, however, unharmed and, despite the inrush of water,

stuck to it until ordered to go on deck.

In spite of having been badly holed by a very effective

German mine, I cannot recall that the ship showed great distress as an

immediate result. By this I mean that there was really no great amount of

trembling in her such as one might reasonably have expected from so great an explosion

– a fact which points clearly to her very solid construction. The list to port

soon began to get worse, although, as is usual in any man-o’-war on occasions

like this, the watertight doors had been closed wherever it had been possible

to get at them.

After the sinking by a German submarine of the British

cruisers Hogue, Cressy and Aboukir in September, 1914, the Admiralty issued

instructions that where a ship was disabled by mine or torpedo whilst in the

company of other ships, she must be left to her fate. We were left to our fate!

About midday, the White Star liner Olympic hove in sight to

the westward. When she was as near to us as her captain, Commodore Haddock,

thought safe, she lowered some of her lifeboats. These with some boats from

destroyers, pulled towards us and managed, by daring seamanship, to get

alongside and take off all but about 200 officers and men. These officers and

men volunteered to remain on board and stand by the ship. She was doomed, so

that there was no object in risking more lives than was necessary, for no one

knew when she might capsize or blow up. Attempts were made to take us in tow,

but they failed. We were so waterlogged and at the mercy of the sea that towing

was impossible.

During the first dog watch, the Captain decided to reduce

our number to about twenty. It was getting dark and the hungry-looking seas

were leaping over the ship, impatiently waiting to claim us. It all looked

pretty hopeless! There was, besides the possibility that the ship might go down

suddenly, the greater risk that the torpedoes and ammunition might break adrift

below and blow us up. Some impression of the state of the sea might be possible

when I say that at times one could see the bow and stem of a destroyer right

out of the water, while her midships was supported on the crest of a huge wave.

Our quarter deck was under water, the main decks forward were awash, and we

had, by this time, a most dangerous list, so about 6.00pm the Captain piped

‘Abandon Ship!’

Only the Captain, Commander, Navigating Officer and myself

now remained on board. It was pitch dark, icy cold and, of course, wet. The sea

was getting more angry and restless. The awful moaning of the swirling water

below decks is unforgettable. At one time I saw what appeared to be boiling oil

oozing up through the seams of the upper decks. We were labouring heavily, and

all but finished.

The Captain, Cecil V. Dampier, and Navigating Officer were

still on the bridge. The Commander, Lancelot N. Turton, and I were standing

together on the break of the foc’s’le. His eyes were wet with tears. He was

about to lose the ship in which dwelt his whole sailor’s heart and soul. I

believe that up to this time he had hoped to save her. His great courage and

endurance, his kindly manner and methods, had been well to the fore all

through. He was a gallant commander, and he knew no fear.

At about 8 o’clock he told me to go round wherever I could,

hailing anyone who might be left on board – perhaps disabled or hurt. I found

no one. The Commander now told me I could go. I left him – still standing alone

on the foc’s’le – to endeavour to find a way of getting clear of the ship.

Swimming was, of course, impossible. I looked all round for something to use as

a raft. There was nothing! Everything movable had been swept overboard. I began

to feel a little dazed when, on the port beam, and almost alongside, I saw a

destroyer’s whaler. I hailed her and her coxswain answered me. Brave lads, that

crew! They might easily have been dashed to pieces against our gunwale.

I waited my opportunity, and jumped – or rather threw myself

into her, and then I must have lost consciousness, for I remember nothing more

until I came to with a basin of rum to my lips in the foc’s’le of the destroyer

Ruby.

We lay off the Audacious, now completely abandoned, until

about 9.00pm, when she blew up and sank. To see the huge pieces of whitehot

metal falling back from the dark sky after the explosion was a sight I shall

not easily forget.

The only serious casualty which resulted from our being mined

was caused by some of the falling debris killing a petty officer on board the

cruiser Liverpool as she was standing off. Not a single man was drowned.

Superstitious people may be interested to know that I was

born with a caul. I am not, myself, superstitious; although I did carry this

caul, hung round my neck by a silver chain, all the years I was at sea! Two

things remain impressed on my memory. Though I had been soaked to the skin and

partially dried again several times, I suffered no ill effects. I cannot

remember having felt any kind of fear for a single moment during the whole long

day. I sometimes tremble now to think of going through such another.