In 336 BCE the aristocrat Pausanias, a member of the king’s

bodyguard and reportedly also his former lover, assassinated Philip II, king of

Macedon. Pausanias was almost immediately slain. Philip’s 20-year-old son

Alexander III (356-323) succeeded to the throne.

Two years before, Philip had defeated the principal Greek

city-states in the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 and made himself master of all

Greece through the Hellenic League, an essential step prior to his planned

great enterprise of invading and conquering the Persian Empire.

On ascending the throne, Alexander quickly crushed a

rebellion of the southern Greek city-states and mounted a short and successful

operation against Macedon’s northern neighbors. He then took up his father’s

plan to conquer the Persian Empire.

Leaving his trusted general Antipater and an army of 10,000

men to hold Macedonia and Greece, in the spring of 334 Alexander set out from

Pella and marched by way of Thrace for the Hellespont (Dardanelles) at the head

of an army of some 30,000 infantry and 5,000 cavalry. Among his forces were men

from the Greek city-states. His army reached the Hellespont in just three weeks

and crossed without Persian opposition. His fleet numbered only about 160 ships

supplied by the allied Greeks. The Persian fleet included perhaps 400

Phoenician triremes, and its crews were far better trained; however, not a

single Persian ship appeared.

Alexander instructed his men that there was to be no looting

in what was now, he said, their land. The invaders soon received the submission

of a number of Greek towns in Asia Minor. King Darius III was, however,

gathering forces to oppose Alexander. Memnon, a Greek mercenary general in the

employ of Darius, knew that Alexander was short of supplies and cash. Memnon

therefore favored a scorched earth policy that would force Alexander to

withdraw. At the same time Darius should use his fleet to transport the army

and invade Macedonia. Unfortunately, Memnon also advised that the Persians

should avoid a pitched battle at all costs. This wounded Persian pride and

influenced Darius to reject the proffered advice.

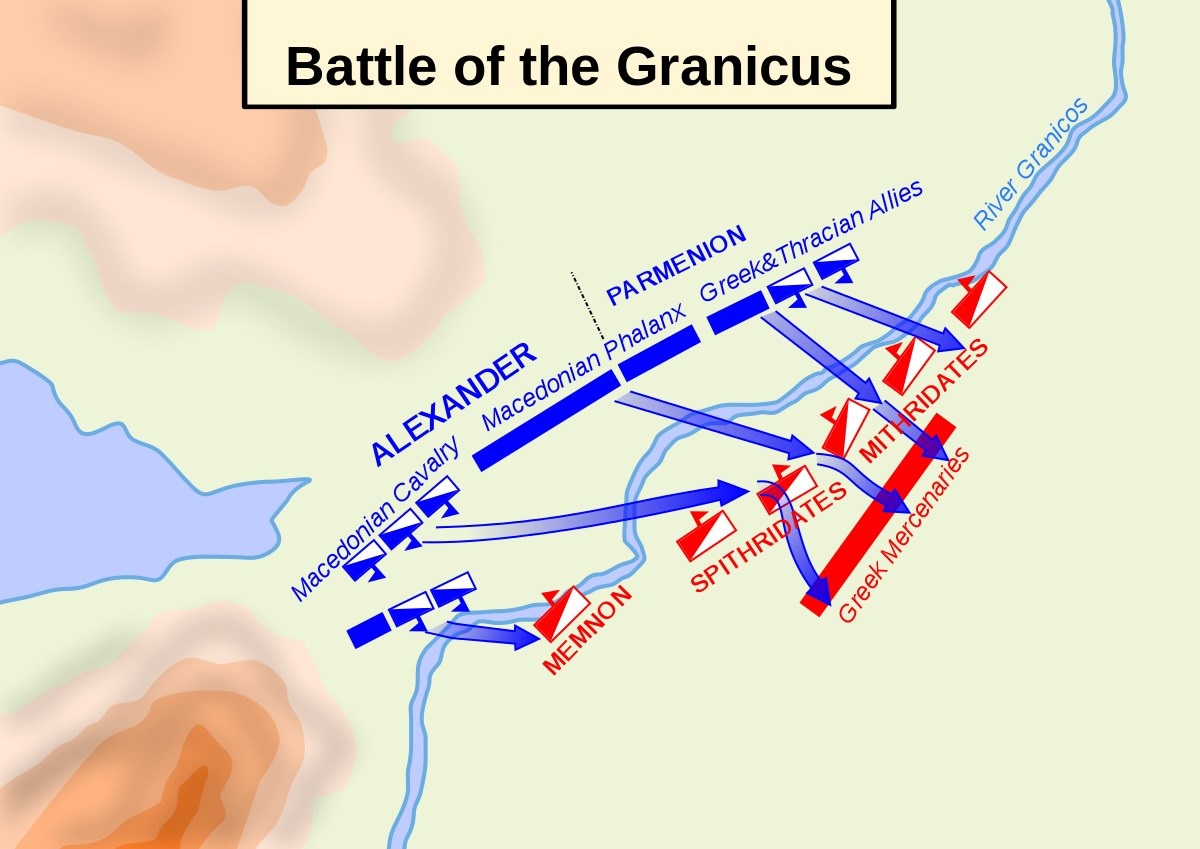

The two armies met in May. The Persian force, which was

approximately the same size as Alexander’s force, took up position on the east

bank of the swift Granicus River in western Asia Minor. The Persians were

strong in cavalry but weak in infantry, with perhaps as many as 6,000 Greek

hoplite mercenaries. Memnon and the Greek mercenaries were in front, forming a

solid spear wall and supported by men with javelins. The Persian cavalry was on

the flanks, to be employed as mounted infantry.

When Alexander’s army arrived, Parmenio and the other

Macedonian generals recognized the strength of the Persian position and

counseled against an attack. The Greek infantry would have to cross the

Granicus in column and would be vulnerable while they were struggling to

re-form. The generals urged that since it was already late afternoon, they

should camp for the night. Alexander was determined to attack but eventually

followed their advice.

That night, however, probably keeping his campfires burning

to deceive the Persians, Alexander located a ford downstream and led his army

across the river. The Persians discovered Alexander’s deception the next

morning. The bulk of the Macedonian army was already across the river and

easily deflected a Persian assault. The rest of the army then crossed.

With Alexander having turned their position, the Persians

and their Greek mercenaries were forced to fight in open country. Their left

was on the river, and their right was anchored by foothills. The Persian

cavalry was now in front, with the Greek mercenary infantry to the rear.

Alexander placed the bulk of his Greek cavalry on the left flank, the heavy

Macedonian infantry in the center, and the light Macedonian infantry, the

Paeonian light cavalry, and his own heavy cavalry (the Companions) on the right

flank. Alexander was conspicuous in magnificent armor and shield with an

extraordinary helmet with two white plumes. He stationed himself on the right

wing, and the Persians therefore assumed that the attack would come from that

quarter.

Alexander initiated the battle. Trumpets blared, and

Alexander set off with the Companions in a great wedge formation aimed at the

far left of the Persian line. This drew Persian cavalry off from the center,

whereupon Alexander wheeled and led the Companions diagonally to his left,

against the weakened Persian center. Although the Companions had to charge

uphill, they pushed their way through a hole in the center of the Persian line.

Alexander was in the thick of the fight as the Companions drove back the

Persian cavalry, which finally broke.

Surrounded, the Greek mercenaries were mostly slaughtered.

Alexander sent the 2,000 who surrendered to Macedonia in chains, probably to

work in the mines. It would have made sense to have incorporated them into his

own army, but Alexander intended to make an example of them for having fought

against fellow Greeks.

Figures for the Persian losses range from 10,000 to 20,000

infantry and around 2,000 horse. These estimates are almost as incredible as

the allegedly minute Macedonian losses, which have been variously put at a maximum

of 30 infantrymen (minimum 9) and 120 cavalry of whom 25 were Companions killed

in the first charge.

After the Granicus

The result of the Granicus battle must have reaffirmed the

faith placed by the Persian king, Darius III, in Memnon. The Greek mercenary

commander’s strategy had been sound. He had wished to avoid a pitched battle,

conduct a scorched-earth policy in Asia, fortify maritime and naval bases on

the coast and cut Alexander off from the sea. While Memnon himself survived,

there were still considerable prospects of putting this plan into effect.

However, many coastal cities, as well as the important road junction of Sardis,

soon fell to Alexander with little or no resistance. Miletus held out in the

hope of relief from a Persian force inland. It also received encouragement from

Phoenician and Cyprian ships based on Mycale. But Alexander forestalled both

naval and military relief and captured the city. Memnon fell back on

Halicarnassus and fortified it strongly. Driven from there, he tried to

establish naval bases on the major Aegean islands, not only threatening

Alexander’s flank from the sea but providing a springboard for a

counter-offensive against Greece and Macedon. Unfortunately for the Persians,

Memnon suddenly fell ill and died. Those who inherited his command persisted

for some time in the same strategy, but were eventually deterred by quite a

small show of naval strength by Antipater, the Macedonian governor whom

Alexander had left in charge of mainland Greece.

Alexander had left Parmenio with the main body of the army

at Sardis. With his own striking force, he marched round the south-west

extremity of Asia Minor and along the southern coast, digressing northward to

join Parmenio again at Gordium in the interior. Strategically, the move seems

superfluous, but Alexander’s expeditions sometimes wore the aspect of

exploration, pilgrimage or even tourism. In any case, he lost no opportunity of

acquainting himself with the features of an empire which he already regarded as

his own.

Having joined forces with Parmenio, Alexander marched

southward again into the Cilician plain and threatened Syria. A Persian force,

inadequate to defend the vital mountain pass, fled at his approach, but the

main Persian army, under command of Darius himself, was waiting farther south

in Syria. At this point, Alexander was suddenly incapacitated by a bout of

fever and his advance was checked.

Emboldened by the delay, Darius made a circuitous march and

descended, by a northern mountain pass, on the town of Issus, where he brutally

put to death the Macedonian sick who had been left there. This manoeuvre placed

him at Alexander’s rear. Alexander was surprised but not dismayed at the move,

for it had carried the Persian army to a point where the plain was pinched

between the mountains and the sea. Here, their superiority in men and missiles

could not be deployed to advantage. However, the position in some ways

resembled that which the satraps had chosen at the Granicus. Darius’ army was

drawn up with a river in front of it; the river was not flowing, since it was

late autumn (334 BC). The king’s mercenary hoplites were placed in the centre.

His cavalry held the wings, his right wing being more heavily loaded, since the

mountains left little room for deployment on the left. He also hoped to break

through on the right wing and cut Alexander off from the sea. It must be

remembered that after Darius’ encircling march the two armies had exchanged

positions.

Much of Alexander’s success seems in general to have been

due to good reconnaissance work. Darius had relied on preventing an outflanking

move from the Companion cavalry by posting a substantial force on the mountain

slopes above. Having ascertained this plan, Alexander provided a light detachment

of his own to mean and ward off the threat. He also sent the Thessalian

cavalry, under Parmenio, to reinforce his left wing. It was possible for

Alexander to make all such changes shortly before battle was joined; his

advance was leisurely, and the Persians kept their positions, leaving him the

initiative.

The battle conformed to the pattern of many ancient battles.

The right wing of the Macedonian army, in encircling the enemy, placed the

central phalanx under strain. As the phalangists on the right strove to

maintain contact with the cavalry on the wing, they parted company with the

phalangists on their left and a dangerous gap appeared, which Darius’ Greek

mercenaries were quick to exploit. It then became a question of whether

Alexander with his Companions could encircle the mercenaries before the

mercenaries could break through the centre and encircle him. Alexander won,

ploughing devastatingly into the mercenary flank and rear. In danger of

capture, Darius fled precipitately in his war-chariot, and even the Persian

forces of the right, who had held back Parmenio’s cavalry, soon followed their

king’s example. Darius’ mother, wife and children, who had accompanied the

army, were left prisoners in Alexander’s hands

References

Green, Peter. Alexander of Macedon, 356-323 B. C.: A

Historical Biography. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991. Hammond,

Nicholas G. L. Alexander the Great: King, Commander, and Statesman. 3rd ed.

London: Bristol Classical Press, 1996. Sekunda, Nick, and John Warry. Alexander

the Great: His Armies and Campaigns, 332–323 B.C. London: Osprey, 1988