Early medieval Europeans received from their predecessors

two broad ranges of wooden shipbuilding traditions, one in the Mediterranean

and the other in the northern seas. At the same time Chinese shipwrights had

already developed the central features of the design of the junk. Its

watertight compartments, adjustable keel, and highly flexible number of masts

each carrying a lug sail with battens, made the junk a highly versatile and

reliable seagoing ship. Junks by the year 1000 were much larger than any ships

in Europe or in the great oceanic area where a Malaysian shipbuilding tradition

predominated. There, ocean-going rafts with outriggers or twin hulls and rigged

with, at first, bipole masts ranged much more widely than vessels from any

other part of the world carrying the designs and building practices across the

Indian Ocean to Madagascar and around the Pacific Ocean to the islands of

Polynesia. Along the shores of the Arabian Sea shipbuilders constructed dhows,

relatively shallow cargo vessels rigged with a single triangular or lateen

sail. The planks of the hulls were typically sewn together with pieces of rope,

a loose system which made the hull flexible, and so able to handle rough seas,

but not very watertight. There were also serious limitations on how big such

hulls could be built, unlike junks where vessels of one thousand tons and more

seem to have been feasible.

Mediterranean Practice

Roman shipbuilders followed Greek practices in building

their hulls with mortise and tenon joints. Wedges or tenons were placed in

cavities or mortises gouged out of the planks and held in place by wooden nails

passed through the hull planks and the tenons. In the Roman Empire the methods

of fastening predominated on all parts of ships, including the decks, and the

tenons were very close to each other. The resulting hull was extremely strong,

heavy, and sturdy so the internal framing was minimal. The hull was also very

watertight but even so the surface was often covered with wax or even copper

sheathing to protect it from attack by shipworm (Teredo navalis). Propulsion

came from a single square sail stepped near the middle of the ship. Often the

mainsail was supplemented with a small square sail slung under the bowsprit.

Roman shipbuilders produced vessels of two general categories, round ships with

length-to-breadth ratios of about 3:1 propelled entirely by sails, and galleys

with length-to-breadth ratios of about 5:1 propelled both by the standard rig

and by oars. Although it was possible to have multiple banks of rowers, in the

Roman Empire there was typically only one, with each rower handling a single

oar. Shipbuilders gave all those vessels at least one but often two side

rudders for control.

As the economy declined in the early Middle Ages and the

supply of skilled labor was reduced, the quality of shipbuilding deteriorated.

The distance between mortise and tenon joints increased, and on the upper parts

of hulls such joints disappeared entirely with planks merely pinned to internal

frames. The trend led by the end of the first millennium C.E. to a new form of

hull construction. Instead of relying on the exterior hull for strength,

shipbuilders transferred the task of maintaining the integrity of the vessel to

the internal frame. The process of ship construction as a result reversed, with

the internal ribs set up first and then the hull planks added. The planks were

still fitted end-to-end as with the old method but now to maintain

watertightness they needed to be caulked more extensively and more regularly. The

internal frames gave shape to the hull so their design became much more

important. The designer of those frames in turn took on a significantly higher

status, the hewers of the planks a lesser position. The new type of

skeleton-first construction made for a lighter and more flexible ship which was

easier to build, needed less wood, but required more maintenance. Increasing

the scale of the ship or changing the shape of the hull was now easier.

Builders used the new kind of construction both on large sailing round ships

and oared galleys.

In the course of the early Middle Ages Mediterranean vessels

went through a change in rigging as well. Triangular lateen sails were in use

in classical Greece and Rome for small vessels. As big ships disappeared with

the decline of the Roman Empire and economy the lateen sail came to dominate

and square sails all but disappeared. Lateen sails had the advantage of making

it possible to sail closer to the wind. Lateen sails had the disadvantage that

when coming about, that is changing course by something of the order of ninety

degrees, the yard from which the sail was hung had to be moved to the other

side of the mast. In order to do that the yard had to be carried over the top

of the mast, which was a clumsy, complex, and manpower-hungry operation. There

was a limitation then on the size of sails and thus on the size of ships. It

was possible to add a second mast, which shipbuilders often did both on galleys

and on round ships since that was the only way to increase total sail area.

Northern European Practice

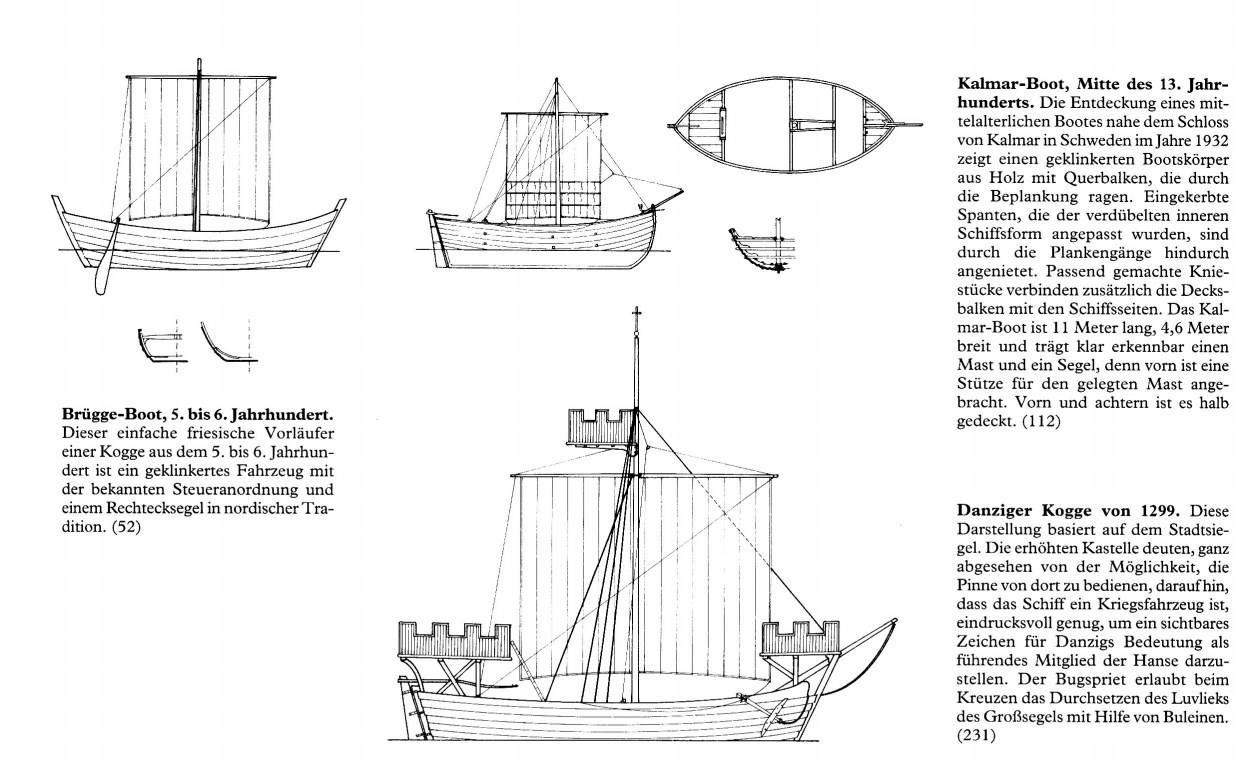

Shipbuilders around the Baltic and North Seas in the early

Middle Ages produced a variety of different types of vessels which were the

ancestors of a range of craft that melded together over the years to create one

principal kind of sailing ship. The rowing barge was a simple vessel with

overlapping planking. The planks could be held fast by ropes but over time

shipbuilders turned to wooden nails or iron rivets for the purpose. That type

of lapstrake construction for hulls meant that internal ribs were of little

importance in strengthening the hull. At first shipwrights used long planks

running from bow to stern but they discovered that by scarfing shorter pieces

together not only did they eliminate a constraint on the length of their

vessels but they also increased the flexibility of the hulls. At some point,

probably in the eighth century, the rowing barge got a real keel and also a

single square sail on a single mast stepped in the middle of the ship. The new

type, with both ends looking much the same, was an effective open ocean sailor.

Scandinavian shipbuilders produced broadly two versions of what can be called

the Viking ship after its most famous users. One version was low, and fitted

with oars and a mast that could be taken down or put up quickly and with a

length-to-breadth ratio of 5:1 or 6:1. The other version had a fixed mast, few

if any oars at the bow and stern which were there just to help in difficult

circumstances, and a length-to-breadth ratio of around 3:1. Both types had a

single side rudder which apparently gave a high degree of control. The Viking

ship evolved into a versatile cargo ship which was also effective as a military

transport and warship. Often called a keel because of one of the features which

allowed it to take to the open ocean, it was produced in variations throughout

northern Europe and along the Atlantic front as far south as Iberia.

The other types that came from early medieval northern

shipyards were more limited in size and complexity. The hulk had a very simple

system of planking which gave way over time to lapstrake construction. The hull

had the form of a banana and there was no keel so it proved effective in use on

rivers and in estuaries. The hull planks, because of the shape of the hull, met

at the bow in a unique way and were often held in place by tying them together.

Rigging was a single square sail on a single mast which could be, in the case

of vessels designed for river travel, set well forward. The cog had a very

different form from the hulk. While the planks on the sides overlapped there

was a sharp angle between those side planks and the ones on the bottom. Those

bottom planks were placed end-to-end and the floor was virtually flat. With

posts at either end almost vertical the hull was somewhat box-like. The type

was suited to use on tidal flats where it could rest squarely on the bottom

when the tide was out, be unloaded and loaded, and then float off when the tide

came in. There was a single square sail on a single mast placed in the middle

of the ship. The design certainly had Celtic origins but it was transformed by

shipwrights in the High Middle Ages to make it into the dominant cargo and

military vessel of the North.

Shipbuilders, possibly in the Low Countries, gave the cog a

keel. In doing that they also made changes in the form of the hull, overlapping

the bottom planks and modifying the sharp angles between the bottom and side

planks. The result was a still box-like hull which had greater carrying

capacity per unit length than keels. The cog could also be built higher than

its predecessors but that meant passing heavy squared timbers through from one

side to the other high in the ship to keep the sides in place. Shipbuilders

fitted the hull planks into the heavy posts at the bow and stern and also fixed

a rudder to the sternpost which was more stable than a side rudder. In the long

run it would prove more efficient as well. Cogs could be and were made much

larger than other contemporary vessels. Greater size meant a need for a larger

sail and a larger crew to raise it. To get more sail area sailors added a

bonnet, an extra rectangular piece of canvas that could be temporarily sewn to

the bottom of the sail. That gave the mariners greater flexibility in deploying

canvas without increasing manning requirements. Riding higher in the water and

able to carry larger numbers of men than other contemporary types cogs became

the standard vessels of northern naval forces, doubling as cargo ships in

peacetime.

While the two shipbuilding traditions of the Mediterranean

and northern Europe remained largely isolated through the early and High Middle

Ages, from the late thirteenth century both benefited from extensive contact

and borrowing of designs and building methods. Sailors in southern Europe used

the cog certainly by the beginning of the fourteenth century and probably

earlier. Shipwrights in the Mediterranean appreciated the advantages of greater

carrying capacity but they were also conscious of the limitations set by the

simple rig. They added a second mast near the stern and fitted it with a lateen

sail. They also changed the form of hull construction, going over to

skeleton-first building. The result was the carrack, in use by the late

fourteenth century. It was easier to build, probably lighter than a cog of the

same size, and could be built bigger. Most of all the two masts and the

presence of a triangular sail gave mariners greater control over their vessels

and made it possible for them to sail closer to the wind. The next logical

step, taken sometime around the end of the fourteenth century, was to add a

third small mast near the bow to balance the one at the stern. The driving sail

and principal source of propulsion was still the mainsail on the mainmast but

the combination or full-rig made ships more maneuverable and able to sail in a

greater variety of conditions. While older forms of ships, such as the keel or

the cog or the lateen-rigged cargo ship of the Mediterranean, did not by any

means disappear, the full-rigged ship came to dominate exchange over longer

distances, especially in the form of the full-rigged carrack travelling between

southern and northern Europe. Northern Europeans were slow to adapt to

skeleton-first hull construction, in some cases even combining old methods with

the new one. By the end of the fifteenth century the full-rigged ship was the

preferred vessel for many intra-European trades, in part because of its

handling qualities, in part because of its versatility, and in part because its

crew size could be reduced per ton of goods carried compared to other types.

The greater range also led to its replacing, for example, the simpler, lower,

lateen-rigged caravel in Portuguese voyages of exploration along the west coast

of Africa. Full-rigged ships in daily use were the choice for voyages of

exploration and became in the Renaissance the vehicles for European domination

of the ocean seas and for the resulting international trading connections and

colonization.

NAVIGATION (ARAB)

The Arabian Peninsula, surrounded by the Red Sea, the Indian

Ocean, and the Arabian (or Persian) Gulf, had a geostrategic position in

relations between East and West. Before the beginning of Islam in 622 the Arabs

had had some nautical experience which was reflected in the Qur’an (VI, 97: “It

is He who created for you the stars, so that they may guide you in the darkness

of land and sea”; XIV, 32: “He drives the ships which by His leave sail the

ocean in your service”; XVI, 14: “It is He who has subjected to you the ocean

so that you may eat of its fresh fish and you bring up from it ornaments with

which to adorn your persons. Behold the ships plowing their course through

it.”) and in ancient poetry (some verses of the poets Tarafa, al-A‘sha’, ‘Amr

Ibn Kulthum, and others). Arabs used the sea for transporting goods from or to

the next coasts and for the exploitation of its resources (fish, pearls, and

coral). However, their experience in maritime matters was limited due to the

very rugged coastline of Arabia with its many reefs and was limited to people

living on the coast. Because they lacked iron, Arab shipwrights did not use

nails, but rather secured the timbers with string made from palm tree thread,

caulked them with oakum from palm trees, and covered them with shark fat. This

system provided the ships with the necessary flexibility to avoid the numerous

reefs. The Andalusi Ibn Jubayr and the Magribi Ibn Battuta confirm these

practices in the accounts of their travels that brought them to this area in

the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, respectively. Ibn Battuta also notes

that in the Red Sea people used to sail only from sunrise to sunset and by

night they brought the ships ashore because of the reefs. The captain, called

the rubban, always stood at the bow to warn the helmsman of reefs.

The regularity of the trade winds, as well as the eastward

expansion of Islam, brought the Arabs into the commercial world of the Indian

Ocean, an experience that was reflected in a genre of literature which mixes

reality and fantasy. Typical are the stories found in the Akhbar al-Sin

wa-l-Hind (News of China and India) and ’Aja’ib al-Hind (Wonders of India), as

well as the tales of Sinbad the Sailor from the popular One Thousand and One

Nights. But medieval navigation was also reflected in the works of the pilots

such as *Ahmad Ibn Majid (whose book on navigation has been translated into

English) and Sulayman al-Mahri.

In the Mediterranean

Sea

The conquests by the Arabs of Syria and Egypt in the seventh

century gave them access to the Mediterranean, which they called Bahr al-Rum

(Byzantine Sea) or Bahr al-Sham (Syrian Sea). Nautical conditions were very

different in this sea: irregular but moderate winds, no heavy swells, and a

mountainous coastline that provided ample visual guides for the sailors on days

with good visibility. The Arabs took advantage of the pre-existing nautical

traditions of the Mediterranean peoples they defeated. In addition, we have

evidence for the migration of Persian craftsmen to the Syrian coast to work in

ship building, just as, later on, some Egyptian craftsmen worked in Tunisian

shipyards.

The Arab conquests of the Iberian Peninsula (al-Andalus) and

islands such as Sicily, Crete, and Cyprus set off a struggle between Christian

and Muslim powers for control of the Mediterranean for trade, travel, and

communications in general. Different Arab states exercised naval domination of

the Mediterranean, especially during the tenth century. According to the

historian Ibn Khaldun, warships were commanded by a qa’id, who was in charge of

military matters, armaments, and soldiers, and a technical chief, the ra’is,

responsible for purely naval tasks. As the Arabs developed commercial traffic

in Mediterranean waters, they developed a body of maritime law which was

codified in the Kitab Akriyat al-sufun (The Book of Chartering Ships). From the

end of the tenth century and throughout the eleventh, Muslim naval power

gradually began to lose its superiority.

In navigation technique, the compass reached al-Andalus by

the eleventh century, permitting mariners to chart courses with directions

added to the distances of the ancient voyages. The next step was the drawing of

navigational charts which were common by the end of the thirteenth century. Ibn

Khaldun states that the Mediterranean coasts were drawn on sheets called

kunbas, used by the sailors as guides because the winds and the routes were

indicated on them.

In the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic coasts of Europe and Africa, despite their

marginal situation with respect to the known world at that time, had an active

maritime life. The Arabs usually called this Ocean al-Bahr al-Muhit (“the

Encircling or Surrounding Sea”), sometimes al-Bahr al-Azam (“the Biggest Sea”),

al-Bahr al-Akhdar (“the Green Sea”) or al-Bahr al-Garbi (“the Western Sea”) and

at other times al-Bahr al-Muzlim (“the Gloomy Sea”) or Bahr al-Zulumat (“Sea of

Darkness”), because of its numerous banks and its propensity for fog and

storms. Few sailors navigated in the open Atlantic, preferring to sail without

losing sight of the coast. The geographer *al-Idrisi in the middle of the

twelfth century informs us so: “Nobody knows what there is in that sea, nor can

ascertain it, because of the difficulties that deep fogs, the height of the

waves, the frequent storms, the innumerable monsters that dwell there, and

strong winds offer to navigation. In this sea, however, there are many islands,

both peopled and uninhabited. No mariners dare sail the high seas; they limit

themselves to coasting, always in sight of land.” Other geographers, including

Yaqut and al-Himyari, mention this short-haul, cabotage style of navigation.

Yaqut observes that, on the other side of the world, in the faraway lands of

China, people did not sail across the sea either. And al-Himyari specifies that

the Atlantic coasts are sailed from the “country of the black people” north to

Brittany. In the fourteenth century, Ibn Khaldun attributed the reluctance of

sailors to penetrate the Ocean to the inexistence of nautical charts with

indications of the winds and their directions that could be used to guide

pilots, as Mediterranean charts did. Nevertheless, Arab authors describe some

maritime adventurers who did embark on voyages of exploration.

Fluvial Navigation

Only on the great rivers such as the Tigris, the Euphrates,

the Nile and, in the West, the Guadalquivir was there significant navigation.

It was common to establish ports in the estuaries of rivers to make use of the

banks to protect the ships.

Nautical Innovations

Two important innovations used by the Arabs in medieval

period are worthy of mention: the triangular lateen sail (also called

staysail), and the sternpost rudder. The lateen sail made it possible to sail

into the wind and was widely adopted in the Mediterranean Sea, in view of its

irregular winds. The Eastern geographer Ibn Hawqal, in the tenth century,

described seeing vessels in the Nile River that were sailing in opposite

directions even though they were propelled by the same wind. To mount only one

rudder in the sternpost which could be operated only by one person proved

vastly more efficient that the two traditional lateral oars it replaced.

Although some researchers assert that this type of rudder originated in

Scandinavia and then diffused to the Mediterranean Sea, eventually reaching the

Arabs, it is most likely a Chinese invention which, thanks to the Arabs,

reached the Mediterranean.

Toward Astronomical

Navigation

The Arabs made great strides in astronomical navigation in

the medieval period. With the help of astronomical tables and calendars, Arab

sailors could ascertain solar longitude at a given moment and, after

calculating the Sun’s altitude as it comes through the Meridian with an astrolabe

or a simple quadrant, they could know the latitude of the place they were in.

At night, they navigated by the altitude of the Pole Star. For this operation

Arab sailors in the Indian Ocean used a simple wooden block with a knotted

string called the kamal which was used to take celestial altitudes. They also

knew how to correct Pole Star observations to find the true North. Ibn Majid,

for example, made this correction with the help of the constellation called

Farqadan, which can only be seen in equatorial seas.

The determination of the longitude was a problem without a

practical solution until the invention of the chronometer in the eighteenth

century. Arab sailors probably may have used a sand clock to measure time,

because they knew how to produce a type of glass that was not affected by

weather conditions. So they could estimate the distance that the ship had

already covered, even though speed could not be accurately determined. The

navigational time unit used was called majra, which the geographer Abu l-Fida’

defines as “the distance that the ship covers in a day and a night with a

following wind,” a nautical day that it is the rough equivalent of one hundred

miles.

Bibliography

Bass, George, ed. A History of Seafaring Based on Underwater

Archaeology. London: Thames and Hudson, 1972.

Friel, Ian. The Good Ship: Ships, Shipbuilding and

Technology in England, 1200–1520. London: British Museum Press, 1995.

Gardiner, Robert, ed. The Earliest Ships: the Evolution of

Boats into Ships. London: Conway Maritime Press, 1996.

——, ed. Cogs, Caravels and Galleons The Sailing Ship

1000–1650. London: Conway Maritime Press, 1994.

Hattendorf, John B., ed. Maritime History in the Age of

Discovery: An Introduction. Malabar, Florida: Krieger, 1995.

Hutchinson, Gillian. Medieval Ships and Shipping.

Rutherford: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1994.

Lane, Frederic C. Venetian Ships and Shipbuilders of the Renaissance.

Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1934.

Lewis, Archibald R. and Timothy J. Runyan. European Naval

and Maritime History, 300–1500. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985.

McGrail, Seán. Boats of the World from the Stone Age to

Medieval Times. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Pryor, J. H. Geography, Technology and War: Studies in the

Maritime History of the Mediterranean 649–1571. New York: Cambridge University

Press, 1988.

Unger, Richard W. The Ship in the Medieval Economy,

600–1600. London: Croom-Helm Ltd., 1980.

Fahmy, Aly Mohamed. Muslim Naval Organisation in the Eastern

Mediterranean from the Seventh to the Tenth Century A.D. 2 vols. Cairo: General

Egyptian Book Organisation, 1980.

Lewis, Archibald Ross. Naval Power and Trade in the

Mediterranean, A. D. 500–1000. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1951.

Lirola Delgado, Jorge. El poder naval de Al-Andalus en la

época del Califato Omeya. Granada: Universidad de Granada, 1993.

Picard, Christophe. La mer et les musulmans d’Occident au

Moyen Age. VIIIe–XIIIe siècle. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1997.

Pryor, John H. Geography, Technology and War. Studies in the

Maritime History of the Mediterranean, 649–1571. New York: Cambridge University

Press, 1988.

Tibbetts, G. R. Arab Navigation in the Indian Ocean before

the Coming of the Portuguese being a translation of Kitab al-Fawa’id fi usul

al-bahr wa’l-qawa’id of Ahmad b. Majid al-Najdi. London: Royal Asiatic Society,

1971.