The Chincha Islands War (Spanish: Guerra hispano-sudamericana)

was a series of coastal and naval battles between Spain and its former

colonies of Peru and Chile from 1864 to 1866. The conflict began with

Spain’s seizure of the guano-rich Chincha Islands in one of a series of

attempts by Spain, under Isabella II, to reassert its influence over its

former South American colonies. The war saw the use of ironclads,

including the Spanish ship Numancia, the first ironclad to circumnavigate the world.

Under

the rule of Isabel the II (1843-1868) Spain faced one of the most

interesting and turbulent years of its history. When the young Queen was

crowned, she found a weak country that was far beyond from being the

great power of the past. She also found that the formerly powerful

Spanish Armada had only three main warships, all of them built during

the XVIII century and a couple of frigates and steamers, which was a

clear contrast with the 177 warships that the country had in 1790.

Isabel

tried to recover the military prestige that the Kingdom had until the

battle of Trafalgar, in which the British wiped out its impressive

armada. She encouraged the construction of a modern and powerful fleet,

which in few years turned Spain into the world’s fourth naval power.

Between 1859 and 1860, 170 million of pesetas, an enormous amount for

those days, were allocated for the construction of new warships. The

result was a mighty squadron composed of six iron-protected frigates,

eleven first class frigates and twelve steam corvettes, plus dozens of

transports and smaller warships. Few times in her history Spain had

assembled such an important and respectable fleet.

Despite

her internal problems, Spain became again a colonial power, and backed

by her naval might, by the end of the 1850´s the kingdom was

participating in several overseas interventions and internal conflicts.

During the second Government of former Governor of Cuba, Leopoldo

O´Donnell (1858-1863), Spain engaged in a war against Morocco (Tetuan),

in a conflict in Indochina (Vietnam), in the French-lead invasion of

Mexico and in the brief annexation of the Dominican Republic.

Soon it was the turn of South America.

At

the end of 1862, the Spanish Queen approved the sending of a so-called

“scientific expedition” to Latin American waters. The expedition was

placed under command of Rear Admiral Luis Hernandez Pinzon –a direct

descendant of the Pinzon brothers who accompanied Christopher Columbus

in the discovery of the New World- and was escorted by three warships:

The twin steam frigates Triunfo and Resolucion and the schooner Virgen

de Covadonga. However, beside scientific research, one of the purposes

of the trip was to support the claims of Spanish citizens living in the

Americas.

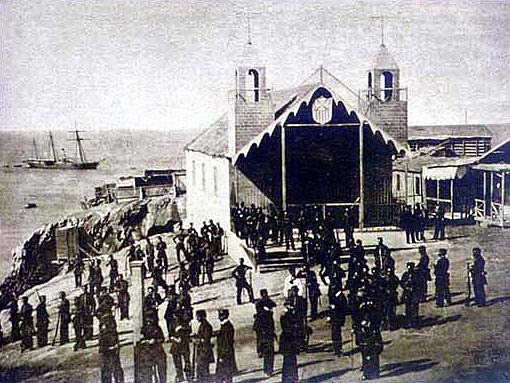

On April 18, 1863, the Spanish

fleet arrived at the Chilean port of Valparaiso. While in Chilean waters

the officers and men were cordially received and the Spaniards

responded in kind. But in July of that year, once in Peru, the problems

started. At that time Spain did not have diplomatic relations with Peru

neither had recognized its independence obtained in 1821. Despite this

situation, the expedition was received with friendly demonstrations by

the authorities. Unfortunately, on August 2, and for reasons still not

clear, an incident occurred in the northern Hacienda of Talambo between

Spanish Basques immigrants and Peruvian nationals. As a result, one

Spaniard was killed and four others injured.

Informed

about this, Pinzon, who was on his way to San Francisco, California,

returned to Peru with his fleet. The Spanish commanding officer

attempted to interfere in what many Peruvians thought was an internal

affair and requested reparations for the incident. Later, the Government

in Madrid also demanded the immediate solution of some pending issues,

such as the payment of debts originated in the wars of independence. To

negotiate these issues, a special emissary, Eusebio Salazar y Mazaredo,

invested as a Royal Commissioner, was sent to deal with the Peruvian

Government. Peru resented the title of Mazaredo, since a Commissioner

was supposed to be a colonial officer and not an Ambassador, which was

the proper title for a diplomatic envoy to a free and Sovereign State.

Mazaredo, who arrived in Peru on March 1864, tried unsuccessfully to

reach an agreement with the Peruvian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Juan

A. Ribeyro.

In response, on April 14th,

1864, the Spanish squadron moved from Callao towards the islands of

Chincha, the major source of Peruvian guano fertilizer. The small

Peruvian garrison was forced to surrender and at 16:00 hours, a

detachment of 400 Spanish marines seized the islands, raised their flag

and placed Governor Ramon Valle Riestra under arrest aboard the

Resolucion. To have an idea about the importance of those islands to

Peru, it must be said that nearly 60% of the Government expenditures

came from the custom duties from guano. Spain wanted to use the rich

islands as a bargaining tool for their demands, and even an ambitious

Spanish Minister back in Madrid proposed to swap them with the British

for Gibraltar.

The Spaniards also blockaded

Peru’s major port and placed the country into turmoil and anger. Even

if during a first stage the Spanish Government of the new Prime Minister

Jose Maria Narvaez did not approve the unilateral action taken by

Pinzon and Salazar, over the next months he changed his mind and sent

four more warships to reinforce the squadron. Narvaez also replaced

Pinzon with the more capable Rear Admiral Juan Manuel Pareja, a former

Minister of the Navy who, coincidentally, was born in Peru. His father,

an army officer, was killed during the wars of independence, and Pareja

disliked the “rebels” for that.

Admiral

Pareja arrived on Peru on December 1864 and engaged in intense

diplomatic negotiations with retired General Manuel Ignacio de Vivanco,

the special representative of the Peruvian President. The negotiations

concluded on January 27, 1865, with a preliminary agreement signed

aboard the Spanish frigate Villa de Madrid. However, most of the

population rejected the Vivanco-Pareja Treaty because it was very

humiliating for Peru. Congress did not ratify it and a revolution

against the Pezet Government exploded in the city of Arequipa months

later.

Meanwhile, anti-Spanish sentiments

in several South American countries such as Bolivia, Chile and Ecuador

were increasing. It was obvious that the Spaniards had no intention to

conquer again their former colonies. Neither they had the strength, nor

the resources to do it, but it was possible that the Government of

Madrid, while presenting a crusade of honor in the Pacific was trying to

distract attention from domestic problems. It was understandable that

after what had happen in Mexico and Santo Domingo, Peru and its

neighbors were suspicious about the possibility of the re-establishment

of the Spanish Empire. For this reason it was not surprising that when

the Spanish gunboat Vencedora stopped at a Chilean port for coal, the

President of that country declared that coal was a war supply that could

not be sold to a belligerent nation. However, from the Spanish point of

view such embargo could not be taken as proof of Chilean neutrality

since two Peruvian steamers –one of them the Lerzundi- had left the port

of Valparaiso with weapons and Chilean volunteers to fight for Peru. In

consequence, Admiral Pareja took a hard line and demanded sanctions

against Chile, even heavier than those imposed upon Peru. He then headed

with part of his squadron composed of four wooden ships to Chile, while

the Covadonga and the Numancia remained to guard Callao.

On

September 17th, 1865, Admiral Pareja anchored his flagship, the Villa

de Madrid, at Valparaiso and demanded that his flag be saluted with 21

guns. Under the circumstances the proud Chileans refused to salute

Pareja’s Insignia and war was declared one week later. Leopoldo

O´Donnell, who was again Spain’s Prime Minister, backed Pareja. Since

the Spanish Admiral had no troops with which to attempt a landing he

decided to impose a blockade of the main Chilean ports. Even so, his

plan was ridiculous, for in order to blockade Chile’s 1,800 miles of

coastline, Pareja would have needed a fleet several times larger than

what he had at his disposal. The blockade of the port of Valparaiso,

however, caused great damage to Chileans and neutrals.

On

November 8th, 1865, Peruvian President Juan Antonio Pezet was forced to

resign from office and was replaced by his Vice President, General

Pedro Diez Canseco. However, Diez Canseco also tried to avoid a

collision with Spain, and on November 26th General Mariano I. Prado,

leader of the nationalist movement, deposed him. Prado immediately

declared his solidarity with Chile and a state of war with Her Catholic

Majesty’s Government in order to restitute the nation’s honor and

confront Pareja´s insults and humiliations.

Ironically, that same day Admiral Pareja committed suicide. During the last weeks he had been suffering a series of setbacks. He could make no positive advances in his war with Chile, his blockade deteriorated and was ineffective and the crews of the ships were demoralized. The proud Admiral was unaware that the Chileans, in a brilliant naval action, had captured the gunboat Virgen de Covadonga and that during the fight the Spaniards had 4 men dead and 21 wounded (1). When on November 25 the American Consul casually mentioned it to him, the Admiral suffered a nervous collapse. It was too much for him. The Covadonga was the second warship lost by Spain in enemy waters after a fire destroyed the Triunfo a year ago. The next day Pareja dressed in his best uniform, laid down on his bed, and shot himself in the head.

Back in the Peninsula, the Spanish public opinion was enraged and

demanded revenge. Because of the loss of the Virgen de Covadonga, one

newspaper wrote:

“Let our squadron perish in the Pacific if necessary, only let our honor to be saved”

After Pareja´s death, the command of the Spanish squadron went to the Captain of the Numancia, Commodore Casto Mendez Nuñez.

On

December the 5th 1865, Chile and Peru formally signed an alliance to

fight against Spain. The treaty was ratified on January 12, 1866. Two

days later Peru declared war on Spain. Immediately a squadron of the

Peruvian navy under command of Captain Lizardo Montero, composed by the

steam frigates Amazonas and the Apurimac, sailed towards Valparaiso to

join the Chilean fleet. Once there the allied command was placed under

orders of Chilean Admiral Manuel Blanco Encalada, an old but capable

officer.

Rumors spread trough Europe and

panic reached Spanish waters because two new powerful Peruvian ironclads

had sailed from England and were said to be heading towards the port of

Cadiz. The Spaniards were also afraid of hostilities against their

merchant ships sailing in international waters. To prevent such actions

Madrid dispatched to the Atlantic the frigate Gerona, which in time,

near Madeira, would capture a 2000-ton disarmed Chilean cruiser of the

“Super-Alabama” class built in England, and dispatched in secrecy under

the code name “Canton”. The Spaniards will rename her “Tornado” (2). On

the other hand, Peruvian warships will seize three Spanish transports

off the coasts of Brazil while on their way to Chile. The Chilean

Government on its part sent the steamer Maipu to the Straight of

Magellan to intercept the Spanish transports “Odessa” and “Vascongada”.

THE SQUADRONS

Most

people in Spain thought that Peru and Chile were not worthy to fight

against their glorious armada. Such a perception was based upon

prejudices because both countries, as former colonies, were seen as

inferior. Another reason was the lack of knowledge of the South American

reality as well as the presumption by most Western powers of a moral

and material superiority over other countries or territories of their

time. For many Spaniards as most Europeans, there was no difference

between Peru and Morocco or between Chile and the Dominican Republic and

so they thought they could be easily defeated. That was a big mistake

that would carry fatal consequences, as the lost of the Covadonga and

the suicide of the gallant admiral Pareja. Their difficulties however,

were just starting.

The order of

battle of the Spanish and the allied fleets from the arrival of the

scientific expedition to Callao in July 1863 to the naval encounters of

February and May 1866 will go trough many changes because both navies

were reinforced with new units.

The Spaniards had

managed to assemble in South American waters a formidable squadron. It

was composed of the following warships:

Iron-protected frigates

Numancia,

at that time among the most powerful ships of the world (Built in

France, 1863; Weight 7,500-tons; Speed 12 knots; weapons thirty-four

200-mm guns; Armor five and a half iron belt; Crew 620 men).

Steam frigates

Villa

de Madrid, (Built 1862; Weight 4,478-tons; Speed 15 knots; Weapons

thirty 200-mm guns, fourteen 160 mm-guns, two 120-mm guns, plus two

150-mm howitzers and two 80-mm guns for disembarks).

Resolucion,

(Built 1861; Weight 3,100-tons; Speed 11 knots; weapons twenty 200-mm

guns, fourteen 160-mm guns, one revolving 220-mm gun and two 150

mm-howitzers, two 120-mm guns and two 80-mm guns for disembarks).

Almansa,

(Built 1864; Weight 3,980-tons; Speed 12 knots; armament thirty 200-mm

guns; fourteen 160-mm guns and two 120-mm guns. She also had two 150

mm-howitzers and two 80-mm guns for disembarks). This ship would arrive

to the Pacific on April 1866, days before the Dos de Mayo Combat.

Reina Blanca and Berenguela, (Each weighted about 3,800-tons. The first one had 68 guns while the Berenguela had 36 guns).

Schooners

Virgen

de Covadonga, (Built 1864; Weight 445-tons; Speed 8 knots; Weapons two

revolving 200-mm guns at the sides and one revolving 160-mm guns at the

prow). Spain however will lose the ship to the Chileans.

Gunboats

Vencedora, (Built 1861; Weight 778-tons; Speed 8 knots; weapons two 200-mm revolving guns and two 160-mm guns).

The

squadron was reinforced with other small gunboats and transports, among

them the Marques de la Victoria (armed with 3 guns), Maule, Consuelo

and Mataure. It had combined artillery of 250 guns (3).

Among

the two South American allies, Peru had the biggest fleet. Obviously it

could not match the total tonnage and firepower of the Spanish squadron

but neither it was, as some had thought, a third class flotilla that

could be wiped out with a single of Mendez Nuñez ships. On the contrary,

Peru had the most respectable naval squadron on the Western shores of

the continent, managed by competent and professional sailors.

As

Spain did in the 1850´s, Peru had renewed its navy trough the purchase

of last generation warships in the best European shipyards, mainly

British. When the crisis with Spain deepened, the Peruvian Government

decided to increase its fleet in the event of war, and bought two former

Confederate cruisers built in France and ordered the construction of

two seagoing ironclads in England. It also decided to build ironclad of

its own. By 1866 Peru had the following warships:

Frigates

Apurimac, (Built UK, 1854; Weight 1,666-tons; Weapons forty four guns).

Amazonas, (Built UK, 1852; Weight 1,320-tons; Weapons twenty-six 32-pounders and six 64-pounders).

Richmond-Class casemated ram monitors:

Loa

(Built, UK, 1854; redesigned and finished in Peru in 1865; Weight 648

tons; Weapons one 110-pounder and one 32-pounder. Protection iron armor

3-inch thick).

Victoria (Built Peru 1864; Weight 300 tons; Weapons one smoothbore 64-pounder. Protection iron armor 3-inch thick).

Cruisers

Union

(Built France, 1864; Weight 1,600 tons; Speed 12.5 knots; Weapons two

100-pounder guns, two 68 pounders and 12 forty pounders)

America

(Built France, 1864; Weight 1,600 tons; Speed 12.5 knots; Weapons two

100-pounder guns, two 68 pounders and 12 forty pounders)

Ironclads

Independence,

casemate, central battery, ironclad steam frigate (Built UK 1865;

Weight 2004-tons; Speed 12.5 knots; Weapons two 150 pounders, twelve 70

pounders, four 32 pounders and four 9 pounders. Protection 4-inch armor;

Crew 260 men).

Huascar (Built

UK 1865; Weight 1,130-tons; Engine 1,500 horse power; Speed 11.5 knots;

Weapons, Two 300-pound Armstrong’s, two 40-pound pivots Armstrong at the

sides and one 12-pounder at the stern. Protection 4.5 armor in the iron

helmet amidships, 2.5 inches at the ends and 5.5-inches in the

revolving turret. Crew 200 men).

Huascar

was by all means an extraordinary warship. In theory, her 10-inch guns

were capable of destroying any of the wooden Spanish frigates, whose

most powerful guns were 68-pounders, number 2, incapable of piercing the

armor or the Huascar or the Independence

Peru also

had several other warships, including the Tumbes (carrying two rifled

70-pounders), Ucayali (two 32-pound guns, three 24-pounders and one

18-pounder), the Sachaca (armed with six-smoothbore 12-pounders) and the

850-ton General Lerzundi (six guns).

On

September 1864 Peru also bought a brand new steamer in the United

States, the Colon, armed with two-smoothbore 12-pounders. However,

American General Irvin McDowell seized and held the Colon in San

Francisco. The seizure of this ship was later approved by the U.S.

Secretary of War and his additional orders provided that all war

material was required for the use of the United States government, and

nothing of the kind could be purchased or taken from the United States,

especially on the Pacific coast. The Peruvian government protested

against the seizure of the Colon and demanded that the vessel be

released. The American government was slow to act and the order to

release the Colon was not issued until March 14, 1865, more than six

months after the seizure. In the meantime the case had been the subject

of an investigation by a grand jury and an opinion rendered that there

was no cause for the detention of the Colon. Nevertheless the ship was

commissioned in the Peruvian Navy and arrived in time to fight against

the Spaniards.

At the beginning

of the conflict, the Chileans only had the Esmeralda, a 854 ton

British-built corvette commissioned in 1854 and armed with 18 guns, and

the Maipu, a 450 ton steamer built in the United Kingdom in 1855 armed

with four 32 and one 68-pounder guns. Chile also was about to receive

two Alabama class unarmored cruisers from the British, the Chacabuco and

the O´Higgins, originally built for the navy of the “Confederate States

of America”. Unfortunately for the allies those ships could not join

the struggle because London seized them until the end of the war. The

Chilean fleet however was increased with the 412-ton Spanish iron

protected schooner Virgen de Covadonga and the 850-ton steamer General

Lerzundi. The first one captured from the Spaniards and the second one

bought from Peru in early 1866 and renamed as Lautaro.

. . . .

(1) The Tornado was apparently launched at Clydebank in 1863. The vessel had a protective 4″ armor belt surrounding her engines and boilers. She was armed with one 220mm (7.8″) muzzleloading Parrott guns, two 160/15 cal. muzzleloading guns, two 120-mm bronze muzzleloading guns, and two 87- mm/24 cal. Hontoria breechloading guns. She had a crew complement of 202 men. The Tornado has been built a commerce-raider for the North American Confederation. Seized by the British Government in 1863, and acquired in 1865, she was purchased by Chile for 75,000 Pounds through Isaac Campbell & Co.in January or February of 1866. According to some sources the vessel was renamed Pampero. Was captured off Madeira by the Spanish frigate Gerona on August 22, 1866 and renamed Tornado. Commissioned in the Spanish Navy, she was rated as screw corvette in 1870. She was converted to a torpedo-training vessel in 1886. Her hulk was sunk in Barcelona by Nationalist air raid during Spanish Civil War. She was finally broken up after 1939.

(2)

St. Hubert Ch. “The Early Spanish Steam Warships 1834-1870” Warship

International 1983. – # 4. – P.338-367; 1984. – #1. – P. 21-44.

(3)

This episode was known as the Battle of Papudo and was fought 55 miles

north of Valparaiso. The Chileans, following a threat used by Admiral

Lord Thomas Cochrane 45 years before, hoisted a British flag on the

Esmeralda, and when they were close enough to Covadonga, they raised

their own flag and unmercifully bombarded the Spanish ship until her

surrender. Beside the casualties, seven Spanish officers and 115 sailors

were taken prisoners.