The belief that giving birth brings with it a biological

imperative to protect also fuels the widely held idea that mothers of all

species—sparrows, bears, and tigers, as well as humans—will fight to protect

their children against external threats. Taken to its logical extreme, the idea

that a mother will fight against all odds to protect her children leads us from

a mother who fights to defend her children from a threatening individual to one

who fights to defend her children against a threatening army. Not surprisingly,

most stories about women who fought for home and children center on defense.

Historically, mothers who fought to protect their children in time of war

typically did so from a defensive position—often literally a last-ditch effort.

Women guarded the wagons in an army’s baggage train. They dug trenches, rebuilt

fortifications, and carried weapons and water to those who fought. They formed

home guard defense units, training alongside men too old and boys too young to

join the regular army. When necessary, they stood on the walls of besieged

cities or fortresses and repelled invaders with rocks, boiling oil, gunfire,

and defiant words.

The story takes a different turn when Mom goes to war at the

head of an army, as we see when we look at the cases of three female rulers of

small kingdoms who took on the greatest empires of their times in order to

protect or avenge their children.

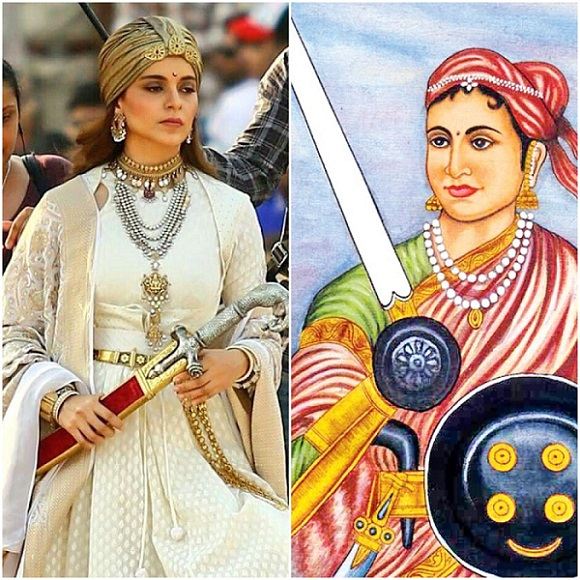

Lakshmi Bai (1828–1858), the Rani of Jhansi, joined the

rebellion against British rule—variously known as the Indian Mutiny, the Sepoy

Rebellion, or the First Indian War of Independence—only when she had no options

left.

Like the Romans before them, the British in India

established relationships with client-kings. Beginning in the mid-eighteenth

century, Indian rulers negotiated with the British East India Company for

military support against other Indian rulers. By 1857, what had once been

protection had become a protection racket. Rulers of the “princely states”

enjoyed personal luxury and titular authority, but British political agents

held the real power in their kingdoms through a combination of fiscal control

and military threat. East India Company troops, made up of Indian soldiers with

British officers and British weapons, were stationed in the princely states.

These troops were officially a royal prerogative but they were also a sword

over the royal head. Only the most powerful and/or lucky Indian states managed

to retain their sovereignty in real terms.

Lakshmi Bai was the widow of Raja Gangadhar Rao Newalkar,

the ruler of the kingdom of Jhansi, which had been a British client state since

1803. Several months before his death, the childless raja adopted a distant

cousin named Damodar Rao as his son and made a will naming the five-year-old

boy as his heir, with Lakshmi Bai as regent. He made sure he took all the steps

needed to make the adoption legal.

Adopted heirs were an accepted practice in Indian

kingdoms—both Gangadhar Rao and his predecessor had been adopted. Unfortunately

for Lakshmi Bai and her son, a new governor-general was in control and making

changes. James Andrew Broun Ramsay, Lord Dalhousie, instituted an aggressive

policy of annexing Indian states on what now (and to many Indians then) seem

flimsy excuses, most notably the doctrine of lapse. The British already

exercised the right to “recognize” (i.e., control) succession in the princely

states with which they had client relationships. Dalhousie now declared that if

the British government in India did not ratify the adoption of an heir to the

throne, the state would pass “by lapse” to the British. Few adopted heirs were

ratified. (Does this surprise anyone?)

When the raja died in 1853, Dalhousie refused to acknowledge

Damodar Rao as the legal heir to the throne and seized control of Jhansi,

replacing the raja with a British bureaucrat. Lakshmi Bai did not initially

oppose the British takeover with violence. Instead she contested the decision

in the British courts, with the support of the prior British political agent at

Jhansi and the advice of British counsel. She continued to submit petitions

arguing her case until early 1856. All her appeals were rejected.

Meanwhile, discontent was building among the Indian soldiers

who made up the vast majority of the British East India Company’s army. The

British made a number of policy decisions that many Indians perceived as an

organized attack on the religious beliefs of both Hindu and Muslim soldiers.

The final straw came when the company handed its Indian troops the hottest new

weapon in the British arsenal: the Enfield rifle. Rumors spread that cartridges

for the Enfield were greased with a combination of beef and pork fat. Since the

cartridges had to be bitten open, such grease would make them abominations for

both Hindus and Muslims. British officers, each certain that the troops under

his command were too loyal to believe anything so foolish, were slow to respond

to the rumors. By the time they assured their men that the cartridges were

greased with beeswax and vegetable oils, the damage was done.

In May 1857, discontent turned to mutiny. Eighty-five sepoys

at the army garrison of Meerut refused to use the new rifles. They were

court-martialed and put in irons. The next day, the regiments stationed at

Meerut stormed the jail, killed the British officers and their families, and

marched toward Delhi, where the last Mogul emperor ruled, at least in name.

The mutiny at Meerut was the spark needed to set off a

revolt that was already loaded, primed, and ready to fire. Thousands of Indians

outside the army had their own grievances against the British. Reforms

regarding child marriage and the protection of widows were seen as attacks on

Hindu religious law. Land reform in Bengal had displaced many landholders.

Members of the traditional nobility resented the forcible annexation of Indian

states and wondered whether theirs would be the next to go. Leaders whose power

had been threatened rose up, transforming what had begun as a mutiny into a

many-headed resistance movement. Violence spread across northern India.

On June 6, the East India Company troops stationed in Jhansi

mutinied. Two days later, they massacred the British population of the city and

marched out to join their counterparts in Delhi. Given Lakshmi Bai’s conflicts

with their government, the British were quick to blame her for the uprising in

Jhansi, though there is no evidence for her initial involvement. In fact, she

wrote to the nearest British authority, Major Walter Erskine, on June 12,

giving her account of the mutiny and asking for instructions. Erskine forwarded

her letter to Calcutta, with a note saying it agreed with what he knew from

other sources. He authorized the rani to manage the district until he could

send soldiers to help her restore order.

With the region in chaos, Lakshmi Bai soon found herself

under attack by two neighboring princes and a distant claimant to the throne of

Jhansi, all of whom saw the crisis as an opportunity to do a little

empire-building of their own. In order to defend her kingdom, she recruited an

army, strengthened the city’s defenses, and formed protective alliances with

the rajas of nearby Banpur and Shergarh. As late as February 1858, she told her

advisors she would turn the district over to the British when they arrived.

Erskine’s positive assessment of the rani’s actions was not

enough. The central government in Calcutta still believed Lakshmi Bai was

responsible for the Jhansi mutiny and subsequent massacre. Her efforts to

defend Jhansi only confirmed that belief.

On March 25, Major General Sir Hugh Rose and his forces

arrived at Jhansi and besieged the city. Threatened with execution as a rebel

if captured by the British, Lakshmi Bai resisted. In spite of a vigorous

defense, by March 30 most of the rani’s guns had been disabled and the fort’s

walls breached. On April 3, the British broke into the city, took the palace,

and stormed the fort.

The night before the final British assault, Lakshmi Bai

escaped from the fortress with her ten-year-old son and four companions. The

next day, the rani and her small retinue reached the fortress of Kalpi. She was

now an official rebel and threw herself into the fight.

Defeated again and again through May and into early June,

Lakshmi Bai and the rebel forces retreated before the British. On June 16,

Rose’s forces closed in. The rani led the remnants of her army into battle. On

the second day of fighting, she was shot from her horse and killed.

Roman historians demonized Boudica. The British response to

the Rani of Jhansi was more complicated. British newspapers denounced Lakshmi

Bai as the “Jezebel of India.” But Rose compared his fallen adversary to Joan

of Arc. Reporting her death to his commanding officer, he said: “The Rani was

remarkable for her bravery, cleverness and perseverance; her generosity to her

subordinates was unbounded. These qualities, combined with her rank, rendered

her the most dangerous of all the rebel leaders. Although she was a lady, she

was the bravest and best military leader of the rebels. A man among the

mutineers.”

Despite the praise of her enemies, Lakshmi Bai failed to

obtain the only thing she wanted from the British: her adopted son received a

pension, but was never recognized as the ruler of Jhansi, which was absorbed

into British India.

The Indian independence movement adopted the Rani of Jhansi as a nationalist icon in the early twentieth century.