The states of the Apennine Peninsula in the second half of the 11th

century.

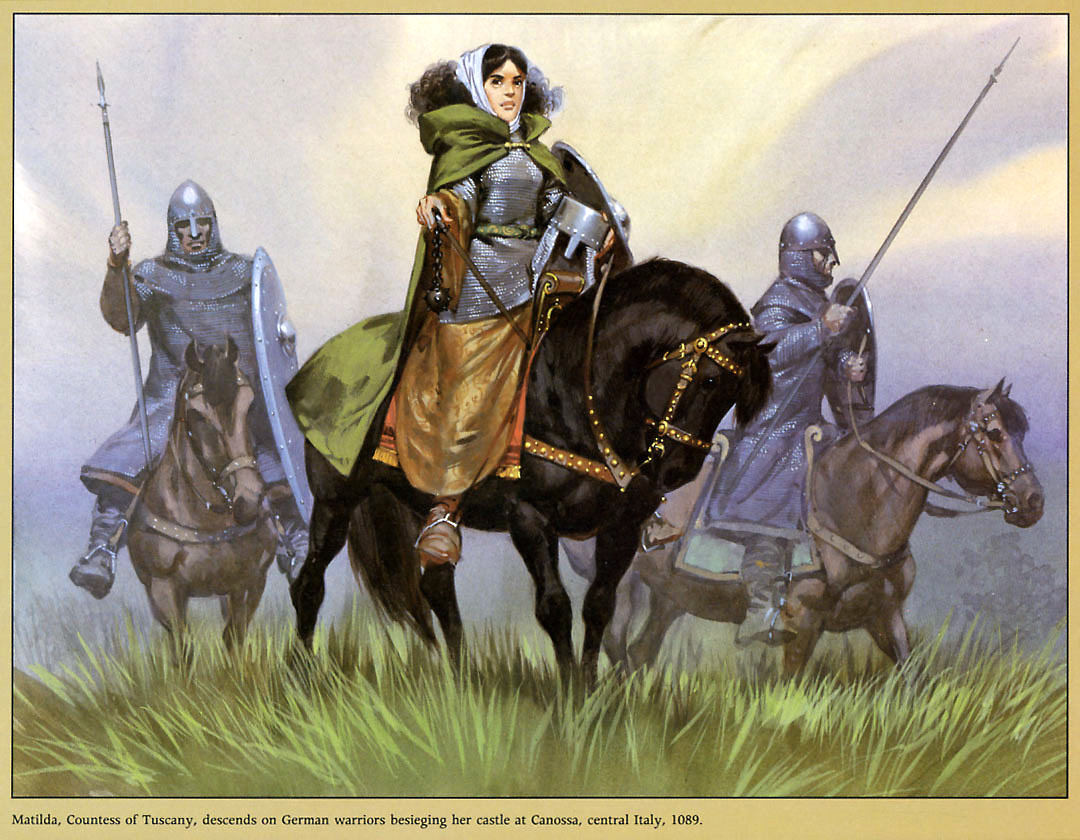

The name Matilda means “mighty in war.” The gran contessa

Matilda of Tuscany (1046–1115) lived up to her name. According to military

historian David Hay, she was not only the most powerful woman of her time but

was among the best European military commanders of her day—high praise for a

woman who at best plays a supporting role in general histories of the period.

Matilda was born in 1046, at the start of the “high middle

ages,” a period when Europe was beginning to recover from the political and

economic chaos left behind by the unraveling of the Roman Empire in the West.

She was the daughter of Margrave Boniface II of Canossa and his second wife,

Beatrice, who was the daughter of the Duke of Upper Lorraine and a military

commander in her own right. Through Beatrice, Matilda was a cousin of the Holy

Roman Emperors Henry III and Henry IV.

Her father’s assassination in 1052 and the subsequent deaths

of her older siblings left Matilda the sole heir to extensive lands. She held

much of the territory between northern Italy and Rome, including a system of

fortresses that controlled access to the two main road systems across the

Apennine Mountains. Although she was pressured twice into marriages that were

politically advantageous to others, she kept control of her inheritance and the

power that went with it at a time when it was not common for women to do so.

In 1076, a long-standing dispute between the papacy and the

Holy Roman Empire flamed into armed conflict. As the ruler of lands lying

directly between the two greatest powers in Latin Christendom, Matilda was

physically in the middle of things.

The Investiture Controversy was the culmination of several

generations of conflict surrounding the relationship between religious and

secular power in general and the relative power of the papacy and the Holy

Roman emperor in particular. The issue at the heart of the controversy was who

controlled appointments to church offices—and the wealth and power church

officials wielded.

Unresolved issues regarding lay investiture of bishops came

to a head with the consecration of the reformist monk Hildebrand as Pope

Gregory VII in 1073. Secular rulers had long claimed the right to appoint

bishops and abbots in their realms and to perform the ritual that installed

them in office. Gregory initiated reforms throughout the church, including a

ban on simony, aka trafficking in ecclesiastical offices. Gregory expanded the

definition of simony to include lay investiture of bishops. His ban on lay

investiture of bishops was not just a religious reform. It also struck at the

power of secular leaders.

The routine appointment of the archbishop of Milan in 1075

provided the spark for ten years of war. Local reformers in Milan had elected a

new archbishop, but after initially accepting the local choice, Emperor Henry

IV attempted to install the chaplain of his Saxon campaign in the position

instead. Gregory ordered Henry to stop interfering in church affairs. In

January 1076, Henry pushed back. He called a council of German bishops and

convinced them to depose Gregory. Gregory then excommunicated the emperor. For

good measure, he excommunicated Henry’s most active supporters among the

bishops.

The potential consequences for Henry were serious. In

theory, excommunicating a monarch absolved his subjects from their obligation

to obey him. In the Kingdom of Germany, where the monarch was elected by his

peers, an excommunicated king could easily be deposed.

Henry discovered he had overestimated the strength of his

position. Many of the German bishops backed away from Henry as fast as their

ceremonial robes would allow and reconciled with the pope. With the validity of

their oaths of allegiance in question, his newly pacified Saxon subjects rose

once again in revolt, while his opponents among the German princes pressed for

the election of a new king. His supporters won Henry a year and a day to free

himself from excommunication before a new king was elected. He needed to grovel

hard and he needed to do it fast.

In January 1077, Matilda and an armed force escorted the

pope through her territory as he traveled toward Augsburg to meet with the

German princes and bishops. When Matilda and Gregory reached Mantua, where he

was scheduled to meet his escort from Germany, they learned Henry was nearby.

Matilda moved the pope from Mantua to her castle at Canossa—a fortress in the

heart of the Apennine Mountains where she could ward off a small imperial force

if necessary.

Matilda was prepared to defend the pope against attack, but

Henry came to Canossa not as an aggressor but as a penitent.

Having crossed the Alps with a small escort, including his

queen and infant heir, through what contemporary chronicles unanimously

describe as unusually severe winter conditions, Henry presented himself at the

gates of Canossa without any of the trappings of royalty. For three days he

stood before the gates, barefoot and dressed in a plain wool robe, begging for

the pope’s mercy—sometimes in tears. Occasionally, he knocked on the door, but

was not allowed to enter. On the fourth day, after negotiations in which

Matilda played a key role, the shivering emperor was allowed into the fortress

to beg face-to-face.

Gregory granted Henry absolution, but the emperor’s

humiliation at Canossa did not end his quarrels with the pope or his problems

in Germany. Despite the fact that Henry had been reinstated in the church, his

opponents back home elected a new king to replace him, Rudolf of Swabia. Both

king and anti-king petitioned Gregory for his support.

At the Lenten synod of 1080, representatives of both

would-be kings presented their petitions to Gregory in person. After hearing

their arguments, Gregory excommunicated Henry a second time, on the grounds

that he had not kept the promises he made at Canossa, and gave Rudolf his

support. Henry convinced another council of German bishops to depose the pope.

This time Henry’s bishops elected an antipope, Archbishop Guibert of Ravenna,

who took the title of Clement III (1080–1100).

On October 15, 1080, Rudolf died in battle. No longer

threatened by the existence of a rival candidate for the crown, Henry returned

to Italy at the head of an army, to settle the question of the papal succession

and his long-delayed coronation as Holy Roman emperor.

Matilda of Tuscany stood in his way.

Matilda had been an ardent supporter of church reform since

childhood. She supported the monk Hildebrand before his election to the papacy

in 1073 and continued to support his efforts after his investiture as Gregory

VII. While Henry and Rudolf faced off in their final battle, Matilda mustered

troops to defend Gregory against Henry and Guibert. She would provide the main

military support for Gregory and his successors in their struggles with Henry

for the next twenty years.

The first battle of the Investiture Controversy took place

in October 1080, as soon as word of Rudolf’s death reached Italy. Henry’s

Italian supporters attacked and defeated Matilda’s troops near her castle at

Volta: the first of several defeats Matilda suffered at the hands of Henry’s

supporters. Matilda was not yet a seasoned commander, unlike her younger cousin

Henry, who had spent most of his adulthood on the battlefield. According to

contemporary accounts from both sides of the conflict, she suffered heavy

losses after Henry entered Italy in the spring of 1081. Bishop Benzo of Alba, a

hard-core Henry supporter, mocked her as “wringing her hands and weeping for

lost Tuscany.”

And yet there are signs Matilda was still a serious force in

Italy. Henry felt threatened enough to convene a court that judged her guilty

of treason for refusing to honor her feudal allegiance to him, placed her under

“ban of empire,” and stripped her of her title and her lands. Like Gregory’s

excommunication of Henry, this act released her vassals from their feudal

obligations.

The ban was easy to pronounce but proved hard to enforce.

Rather than meet Henry’s forces on the battlefield, Matilda retreated to her

fortress at Canossa. While Henry’s main army besieged Rome, Matilda’s forces

attacked Henry’s supply lines and raided the holdings of his northern

supporters from the protection of her network of mountain castles. She kept

Gregory’s communication lines open and provided him with information about

Henry’s movements—military and diplomatic. She exerted enough pressure on Henry’s

allies from her mountain stronghold that by 1082 his beleaguered supporters

insisted he come north and campaign against Matilda in person.

After systematically ravaging the north, Henry besieged Rome

itself. He captured the city on March 21, 1084. With Henry in control of the

city, Guibert was consecrated as pope on March 24. Seven days later, on Easter

Sunday, Guibert returned the favor and crowned Henry as Holy Roman

emperor—which had to be a relief to Henry, who had ruled as king of the Germans

since 1056 without papally approved imperial authority.

With the imperial crown on his head and a consecrated pope

in his pocket, Henry left Rome on May 21, 1084. As he hit the road for Germany,

he ordered his Italian allies to capture Matilda and destroy her fortresses,

which would secure his lines of communication with Rome and gut the military

strength of the papal reformists.

The combined troops of Henry’s supporters marched along the

Via Emilia, through the Po Valley—pillaging as they went. Matilda monitored

their progress from the security of her Apennine fortresses. On the night of

July 1, 1084, her opponents camped on the plain at Sorbara, close to one of

Matilda’s castles. Having crossed the valley from Parma to Modena unopposed,

the invaders grew careless and did not set an adequate guard.

The next day, Matilda led a small force in a dawn raid on

the sleeping camp of Henry’s supporters—the first time she met imperial forces

in open battle in three years. Her troops broke through the camp’s outer

defenses, causing panic among the enemy ranks. They slaughtered large numbers

of fleeing foot soldiers, captured a hundred knights, and took more than five

hundred horses as part of their booty. Matilda lost a handful of her men and

“no one of note”—the medieval assessment of a successful battle. Sorbara was a

major victory in medieval terms and a turning point in the war, giving new hope

to the reform party at the moment when Henry seemed triumphant.

For the next six years, Matilda was on the offensive against

Henry’s supporters. Pope Gregory’s death in exile in 1085 did not end the

conflict. Matilda became the secular rallying point for the reform cause and

the armed supporter of two reformist popes in succession: Victor III, whose

papacy lasted only four months, and Urban II, who completed Gregory’s reforms,

launched the first crusade, and left the papacy stronger than he found it.

In the spring of 1090, Henry mounted a counterattack. He

seized Matilda’s remaining lands in Lorraine, then invaded northern Italy. Over

the next two years, he drove his armies toward Canossa. He took city after

fortress after city with a combination of military victories and bribery. (The

promise of imperial privilege, in which an autonomous town owed fealty only to

the emperor, was a tempting offer to towns held in feudal tenure to a

more-or-less local lord.) When she lost Mantua and Verona, the first to bribery

and the second to betrayal, Matilda fell back south of the river Po. Henry

continued to press her.

In September 1092, after a string of imperial victories,

Henry offered Matilda generous peace terms if she would recognize Guibert of

Ravenna as Pope Clement III. Against the advice of many of her supporters, she

refused.

That October, Henry moved against Canossa, hoping to force

Matilda to surrender by trapping her in her fortress. Warned of his approach,

Matilda withdrew with an armed force to an outlying castle. After Henry

exhausted his troops against Canossa, she attacked. Henry’s siege turned into a

rout, with Matilda’s forces harassing the emperor’s troops as they retreated in

disorder across the Po.

Henry remained in Italy for the next three years, but the

war was effectively over.

Whether or not Matilda actively fought, sword in hand, she

was a “combatant commander” by any standard. Over the course of a forty-year

military career, Matilda mustered troops for long-distance expeditions, fought

successful defensive campaigns against the Holy Roman emperor (himself a

skilled commander), launched ambushes, engaged in urban warfare, directed

sieges, lifted sieges, and was besieged. She built, stocked, and fortified

castles. She maintained an effective intelligence network. She negotiated

alliances with local leaders. She rewarded her followers with the favorite

currencies of medieval rulers: land, castles, and privileges.

Matilda fielded her last military action in 1114, putting

down a revolt in the city of Mantua less than a year before her death. Mighty

in war to the end.