Edited from material

by Mike Yaklich, et al

1941

January 1941:

British destroyer Gallant badly damaged by Italian mine near

Malta (later bombed while under repair, never sails again). Italian-flown Ju-87 dive-bomber scores one of

the six bomb hits that severely damage British aircraft carrier

Illustrious. Free French submarine

Narval sunk by destroyer escort Clio.

British merchantman Clan Cumming torpedoed by sub Neghelli but reaches

port. British tanker Desmoulea torpedoed

by destroyer escort Lupo (towed back to port).

February 1941:

British gunboat Ladybird damaged (not seriously) by Italian

air attack during unsuccessful commando raid on island of Kastelorizo. Italian bombing raids on Benghazi force the

British to stop using the port for the time being.

March 1941:

British heavy cruiser York severely damaged (beached, never

sailed again) and tanker Pericles sunk by Italian “explosive

motorboats” (launched from destroyers Crispi and Sella) in Suda Bay. British light cruiser Bonaventure sunk by Italian

sub Ambra.

April 1941:

British destroyer Mohawk torpedoed and sunk by Italian

destroyer Tarigo (itself also sinking) in action against Italian convoy off the

Kerkenah light buoy. British tanker

British Science (7,300 tons) sunk by SM79 torpedo planes. Greek destroyer escort Proussa sunk by

Italian Ju-87s. Small freighter Susanah (900 tons) hit by Italian Ju-87s,

beached, later destroyed in another attack by Italian Ju-87s. British fleet oiler British Lord damaged by

SM79 torpedo planes. British salvage

vessel Viking sunk by SM79s. Freighter Devis (6,000 tons) damaged by SM81s

(multiple bomb hits, seven men killed, 14 wounded, on fire but rejoins British

convoy). (1)

May 1941:

During battle of Crete, British destroyer Juno sunk by

Italian Z1007s in level bombing attack; destroyer Imperial sunk by Italian SM84

bombers; light cruiser Ajax damaged (20 serious casualties) by Italian SM84s.

(2) British submarine Usk sunk either by Italian destroyers (Pigafetta and

Zeno) or Italian mines. British submarine

Undaunted sunk either by Italian destroyer escorts (Pegaso or Pleiadi) or

Italian mines. British transport

Rawnsley hit by SM79 torpedo planes (previously damaged by German bombers-

towed to Crete after Italian attack, later sunk there). British gunboat Ladybird sunk by Italian

Ju-87s at Tobruk.

June 1941:

Australian destroyer Waterhen sunk in combined attack by

German and Italian Ju-87s (Italian pilot Ennio Tarantola was credited with a

near-miss that caused serious damage).

July 1941:

During Malta convoy operation, British destroyer Fearless

sunk by SM79 torpedo bombers; British light cruiser Manchester damaged by SM79

torpedo bombers (38 killed, out of action nine months); British destroyer

Firedrake damaged by Italian bomb (boilers and steering out, towed back to

port); freighter Sydney Star torpedoed in attacks by MAS 532 and MAS 533, but

reaches Malta. Tanker Hoegh Hood (9,350

tons), returning to Gibraltar from Malta empty in simultaneous operation, hit

by Italian torpedo plane but makes port.

British destroyer Defender sunk by Italian aircraft off Sidi Barrani.

(3) British sub Union sunk by destroyer

escort Circe. British sub Cachalot

rammed and sunk by destroyer escort Papa.

August 1941:

British light cruiser Phoebe damaged by Italian torpedo

plane (out of action eight months).

British sub P. 32 sunk by Italian mines while trying to enter port of

Tripoli. British sub P. 33 sunk in same

area, presumably by Italian mines.

British tanker Desmoulea damaged by SM79 torpedo planes. Belgian tanker

Alexandre Andre damaged by SM79 torpedo planes. British tanker Turbo sunk by SM79 torpedo

planes. British small armaments carrier

Escaut sunk by SM79 torpedo planes.

British netlayer Protector severely damaged by SM79 torpedo planes (out

of action four years).

September 1941:

During Malta convoy operation, British battleship Nelson

damaged by SM84 torpedo bombers (one torpedo hit, out of action six months);

merchantman Imperial Star (12,000 tons) sunk by SM79 torpedo planes. British small tanker Fiona Shell, fleet oiler

Denbydale, and merchantman Durham (11,000 tons) sunk at Gibraltar by

“piloted torpedoes” launched from submarine Scire (however, Denbydale

and Durham settled in shallow water and were both later recovered).

October 1941:

British merchantman (blockade runner to Malta) Empire

Guillemot sunk by SM84 torpedo planes.

British sub Tetrarch presumed sunk by Italian mines off Sicily.

November 1941:

British merchantmen (blockade runners to Malta) Empire

Defender and Empire Pelican sunk by Italian torpedo planes. During sinking of “Duisburg”

convoy, British destroyer Lively suffers minor splinter damage from near misses

of 8-inch shells from Italian heavy cruisers.

December 1941:

British battleships Queen Elizabeth and Valiant, tanker

Sagona, and destroyer Jervis (tied alongside Sagona for fueling) damaged at

Alexandria by “piloted torpedoes” launched from sub Scire (Queen

Elizabeth sank but settled in shallow water:

raised and repaired, out of action almost a year and a half. Valiant out of action eight months. Sagona henceforth used only as a stationary

fuel bunker. Jervis under repair one

month). British light cruiser Neptune,

destroyer Kandahar sunk (only one survivor from Neptune!), light cruisers

Aurora and Penelope damaged by mines laid by light cruisers of Italian 7th

Division (Aurora out of action eight months). British destroyer Kipling suffers

minor splinter damage from near misses (one man killed) during “First

Battle of Sirte.” Small British steamer

Volo (1,500 tons) sunk by SM79 torpedo bombers.

NOTES

(1) Italian SM79s also claimed the sinking of the British

transport Homefield, however according to Shores et al (“The Air War for

Yugoslavia, Greece, and Crete”) the damage that resulted in this ship

being scuttled was inflicted in a later attack by German Ju-88s. Shores states that the Italian torpedo

bombers which claimed a hit were mistaken, and that all damage resulted from

(German) bomb hits.

(2) Italian torpedo bombers also claim to have fatally

damaged British destroyer Hereward during the Crete battle. Bragadin (“The Italian Navy in World War

II”) repeats this claim, and also says that the badly-damaged Hereward was

scuttled as Italian MAS torpedo boats approached. Greene and Massignani (“The Naval War in

the Mediterranean”) accept the account of Shores et al (op cit) that

Hereward was hit by German Ju-87s (although, contrary to much of the book,

Shores does not specify the exact unit or mission for the attacking aircraft),

and refute Bragadin, Sadkovich, and others.

Shores does also note that survivors were picked up by Italian MAS

boats, as do other British accounts. My

own conclusion is that the best evidence is for the ship being fatally damaged

by German air attack, but that the Italians may be accorded a small role, as

the appearance of the MAS probably prompted the decision to scuttle.

(3) A number of

accounts list this as a combined attack by German and Italian planes, but

sources I consulted seemed to agree that Italian aircraft should get either

full or partial credit for the sinking.

1942

January 1942:

British sub Triumph sunk, apparently by Italian mines off

Greek island of Milo.

February 1942:

British sub Tempest sunk by Italian antisubmarine forces,

including destroyer escort Circe.

British sub P. 38 sunk by Italian convoy escorts, again including

Circe. British sub Thresher badly damaged

while attacking Italian convoy.

March 1942:

During Malta convoy operation (“second battle of

Sirte”) British light cruiser Cleopatra hit by 6-inch shell from light

cruiser Bande Nere (radio and antiaircraft fire director knocked out, 15 men

killed: splinters from near misses kill

one more man); light cruiser Euryalus suffers splinter damage from near-miss by

15-inch shell from battleship Littorio; destroyer Kingston hit by 15-inch shell

from Littorio (passes through ship without exploding, but kills 14, wounds 20,

and starts a small fire); destroyer Havock hit by splinters of 15-inch shell

from Littorio (seven killed, nine wounded, one boiler flooded); destroyer

Lively hit by 15-inch splinters from Littorio (minor flooding, funnel on fire);

destroyer Sikh straddled by 15-inch shells, but only minor damage. (4) British destroyer Southwold sunk by Italian

mine outside Malta.

April 1942:

British sub Upholder sunk by destroyer escort Pegaso. British sub Urge sunk (exact cause uncertain,

but all sources which cite cause agree it was to Italian action: most probably Italian mines, possibly to

destroyer escort Pegaso or to Italian aircraft). British subs Pandora and P. 36 sunk by

Italian bombers in raid on port at Malta.

British destroyer Havock torpedoed by sub Aradam, but only after it had

been run aground, abandoned, and largely demolished by its crew. (5)

May 1942:

(None found?)

June 1942:

During Malta convoy operation, destroyer Bedouin sunk by

SM79 torpedo plane, after having been heavily damaged in surface action by

ships of Italian 7th Division (hit by 12 shells, mostly 6-inch, some of which

passed through the ship without exploding); Dutch merchantman Tanimbar (8,000

tons) sunk by SM79 torpedo plane; British light cruiser Liverpool damaged by

SM79 torpedo plane (towed back, out of action almost two years); freighter Burdwan

and tanker Kentucky sunk by ships of Italian 7th Division (both had been badly

damaged in previous air attacks); antiaircraft cruiser Cairo damaged in surface

action with 7th Division (one armor-piercing 6-inch shell- used because the

Italian light cruisers had run out of the more effective high-explosive

ammunition- penetrates fuel bunker but fails to do fatal damage because it

failed to explode); destroyer Partridge damaged by ships of 7th Division

(stopped but gets under way again); minesweeper Hebe hit by one shell from

ships of 7th Division (badly damaged).

(6) British destroyer Nestor,

badly damaged by German air attack but being towed back to port (SM79s also

participated in that attack but scored no hits), is scuttled on appearance of

more Italian aircraft due to the risk to the towing vessel.

July 1942:

Tanker Antares (Turkish but in British service) sunk by sub

Alagi. Small British freighters Meta,

Shuma, Snipe, and Baron Douglas (total approx. 10,000 tons) sunk at Gibraltar

by Italian “frogman” swimmers.

August 1942:

During major Malta convoy operation, British antiaircraft

cruiser Cairo sunk, light cruiser Nigeria damaged (52 killed, severe structural

damage), and tanker Ohio (10,000 tons) damaged by sub Axum (Ohio stopped and on

fire, but fires are extinguished by water pouring in through large torpedo hole

in its side!); light cruiser Manchester sunk by large torpedo boats MS 16 and

MS 22 (each scored one hit); destroyer Foresight sunk by SM79 torpedo bomber;

freighter Glenorchy (9,000 tons) sunk by large torpedo boat MS 31; freighter

Wairangi (12,400 tons) sunk by torpedo boat MAS 552; freighter Almeria Lykes

(7,700 tons) sunk by torpedo boat MAS 554; freighter Santa Elisa (8,300 tons)

sunk by torpedo boat MAS 557; freighter Empire Hope (12,600 tons) sunk by sub

Bronzo after being severely damaged by (German) air attack and abandoned; light cruiser Kenya damaged (three killed,

one wounded; sonar knocked out and extensive flooding- however, the ship

remained with the convoy) by sub Alagi; freighter Rochester Castle (7,800 tons)

damaged by torpedo boat MAS 564, but makes it to Malta; aircraft carrier

Victorious hit by two 1,386-lb bombs by Re2001 fighter-bombers, but one bounces

over the side before exploding, other one does minor damage to flight deck (six

killed, two wounded); aircraft carrier Indomitable hit by one 220-lb bomb by

CR42 fighter-bomber which does minimal damage to flight deck; battleship Rodney

hit by one bomb by Italian Ju-87s, but it bounces off main gun turret before

exploding and does no damage; tanker Ohio damaged again by near-miss from

Italian Ju-87, which buckles bow plates and causes more flooding; freighter

Port Chalmers hit on paravane of minesweeping gear by torpedo from SM79, but

this is cut loose and the torpedo explodes underwater, causing no damage. (7)

British destroyer Eridge damaged beyond repair by MTM small assault

torpedo boats off North African coast (towed back to Alexandria but written

off). British sub Thorn sunk by destroyer escort Pegaso.

September 1942:

During foiled large-scale commando raid on Tobruk, British

destroyer Sikh sunk and destroyer Zulu badly damaged by combined fire of

Italian and German shore batteries (Zulu later sunk by air attack); British

torpedo boats MTB 308, MTB 310, MTB 312, were sunk and MTB 314 was captured [She

was later used by the Germans] in same raid, along with two motor launches, by

Italian MC200 fighter-bombers and/or Italian shore batteries. (8)

British small freighter Raven’s Point sunk at Gibraltar by Italian

swimmers.

October 1942:

(None found?)

November 1942:

British sub Utmost sunk by destroyer escort Groppo. British sloop Ibis sunk by Italian torpedo

plane. British auxiliary antiaircraft

ship Tynwald and troopship Awatea (13,400 tons) sunk by submarine Argo (Awatea

had previously been heavily damaged by bombing). (9)

British minesweeper Algerine sunk by submarine Asciangi. British minesweeper Cromer sunk by Italian

mines off Mersa Matruh. French tanker

Tarn damaged by sub Dandolo but makes port.

December 1942:

British destroyer Quentin sunk by SM79 torpedo bomber. British corvette Marigold sunk by Italian torpedo

planes. British sub P. 222 sunk by

destroyer escort Fortunale. British sub

P. 48 sunk by destroyer escorts Ardente and Ardito. British sub P. 311 sunk by Italian mines

outside port of Maddalena. British light

cruiser Argonaut hit by two torpedoes from sub Mocenigo (only three men killed,

but out of action eleven months). Small

Norwegian freighter Berto (1,400 tons) sunk, freighters Ocean Vanquisher

(7,000 tons), Empire Centaur (7,000 tons), and Armattan

(4,500 tons) damaged in port at Algiers by “piloted torpedoes” and

swimmers launched from sub Ambra.

NOTES

4) There are many conflicting reports of damage inflicted at

Second Sirte. The above reflects only what I have been able to verify from

sources on the British side. The

Italians believed they had also damaged light cruiser Penelope and destroyers

Lance and Legion, and at least one British source I consulted also gives this

information. On the other hand, the

British thought they had torpedoed battleship Littorio and hit light cruiser

Bande Nere and an unidentified heavy cruiser, when in actuality they only

scored one hit, a 120mm (4.7-inch) shell which struck Littorio doing minimal

damage. The fog of war was apparently

very thick in this battle (literally, given the effective British use of

smokescreens), as the Italians thought that Kingston had been hit by a heavy

cruiser, variously reported as Trento or Gorizia, and some Italian accounts

also credit Trento (not Bande Nere) with having hit Cleopatra.

(5) Italian accounts

almost unanimously reverse the cause and effect, saying that Havock was first

torpedoed, and then beached- including eyewitness reports from the crew of

Aradam, which surfaced and reported seeing the British destroyer on fire. I have accepted the British version, not

necessarily incompatible with that eyewitness testimony.

(6) There are claims that Burdwan was crippled by Italian

SM84s which were mistakenly reported as German planes. Kentucky was eventually finished off by the

guns of light cruiser Montecuccoli and a torpedo from destroyer Oriani.

(7) Great confusion surrounds the August 12 night action

against the “Pedestal” convoy, which is perhaps understandable given

repeated attacks by Italian submarines and various Axis aircraft, sometimes

virtually overlapping, over a period of about two hours. Sadkovich (op cit, p. 292-296, citing several

other sources) mentions Italian claims that freighter Brisbane Star was hit by

Italian sub Dessie (a claim often repeated but now generally considered to have

been in error, the sub’s crew probably having heard the successful torpedo hits

of Axum and assumed they were their own); that the sub Alagi also hit the

freighter Clan Ferguson (this is far more

plausible, but as Sadkovich times the attack at 21:18, while Clan Ferguson with

its load of ammunition had been reported hit by a German He-111 torpedo plane

at 21:02, the ship would have already been abandoned, on fire, and rapidly

sinking when this occurred); and that

sub Bronzo also crippled Glenorchy (this ship was at any rate credited to

Italian action, as it was confirmed sunk by an Italian torpedo boat later that

night). Sadkovich also claims that

Italian Ju-87s hit destroyer Ashanti while attacking Ohio on August 13, but I

have been unable to find any other reference which verifies this, or indeed

that Ashanti was damaged at all during “Pedestal” (the ship was

providing close escort to Ohio at a time when Italian Ju-87s scored a near-miss,

and was heavily engaged). Other sources mention Brisbane Star as having been

torpedoed by an SM79 (a possibility, since there were only seven He-111 torpedo

planes involved in the German air attack- the other German aircraft being 30

Ju-88s armed with bombs- and these already appear to have accounted for Clan

Ferguson, the previously-damaged Deucalion, and possibly Empire Hope, which had

a 15-foot hole in its side that sounds like a torpedo hit. However, I have not come across anything that

gives more specifics on any Italian planes involved in these air attacks), and

still other sources list Deucalion as a victim of Italian rather than German

torpedo planes (probably an error).

British destroyer Wolverine had its bows badly damaged when it rammed

and sank Italian sub Dagabur with all hands, but I hesitate to classify that as

“damage inflicted by the Italians,” given the circumstances.

(8) Again, it is difficult to decipher exactly who did what

in this action. By the best accounts, Sikh was hit twice by a German 88mm

battery and took at least three more shells of unknown origin. From accounts of those aboard, the best

reconstruction of its fate seems to be that the ship was crippled by the German

guns and then finished off by the Italian (152mm). Zulu was probably hit by an

Italian battery. The exact identity of

the aircraft that sank Zulu also remains unclear. Many Italian sources credit MC200

fighter-bombers. The MC200s definitely

did effectively bomb and strafe British motor torpedo boats, claiming to sink

three and badly damage a fourth. Another

four British torpedo boats were claimed by Italian shore batteries. British reported losses of small craft, as

seen above, were four torpedo boats and two motor launches.

(9) Italian SM79 torpedo bombers also claimed Awatea in the

original air attacks, but most accounts have it set afire by German Ju-88s.

1943

January 1943:

British corvette Samphire sunk by sub Platino.

February 1943:

British minesweeping trawler Tervani sunk by sub Accaio.

March 1943:

British sub Turbulent sunk either by Italian anti-submarine

trawler or by Italian mines outside La Maddalena. British sub Thunderbolt sunk by corvette

Cicogna.

April 1943:

British destroyer Pakenham sunk as a result of gun battle

with destroyer escorts Cassiopea and Cigno (Cigno was also sunk in this

encounter). British sub Sahib sunk by corvette Gabbiano (after being attacked

by German Ju-88s). British torpedo boat

MTB 639 sunk by destroyer escort Sagittario.

May 1943:

Freighters Pat Harrison (7,000 tons), Marhsud (7,500 tons),

and Camerata (4,800 tons) sunk at Gibraltar by “piloted torpedoes”

operated from derelict freighter Olterra (interned by Spanish at nearby

Algeciras and converted by Italians into secret base for missions against

Gibraltar). British minelayer Fantome

sunk by Italian mines off Bizerte.

June 1943:

(None found?)

July 1943:

During invasion of Sicily, British carrier Indomitable

seriously damaged by SM79 torpedo plane (out of action seven months); British

light cruiser Cleopatra damaged by sub Dandolo (out of action four months); US

transport Timothy Pickering sunk by Re2002s (166 killed, including British

troops aboard); US transport Joseph G Cannon damaged by Re2002s (hit by bomb

which failed to explode, returned to Malta); British torpedo boat MTB 316 sunk

by light cruiser Scipione Africano; sub Flutto inflicts 17 casualties before

being sunk in surface battle with British torpedo boats MTB 640, MTB 651, and

MTB 670. Greek steamship Orion (4,800

tons) sunk by mine planted by Italian swimmer in neutral Turkish harbor one

week earlier (the swimmer, Lt. Luigi Ferraro, smuggled in by undercover agents

of naval intelligence, as were the mines).

Freighter Kaituna (4,900 tons) damaged by mine placed by same swimmer

(Ferraro mined two other ships which were saved by underwater inspections after

British found a second unexploded mine on Kaituna).

August 1943:

Tanker Thorshoud (10,000 tons), freighter Harrison Grey Otis

(7,000 tons), and freighter Stanbridge (6,000 tons) sunk at Gibraltar by

“piloted torpedoes” from Olterra.

British sub Saracen sunk by corvettes Minerva and Euterpe.

September 1943:

(none found?)

French Ships

See below. My

comments marked *.

– French “super-destroyer” Albatros hit by 6-inch

shell from Italian coastal battery during bombardment of Genoa (ten men

killed).

* 14/6/40: the “contre-torpilleur” Albatros was

indeed hit by a 152mm round from the Pegli coastal battery; 12 men in all died

from burn wounds.

– Small freighter Elgo (1,900 tons) sunk by sub Capponi

while en route to a French North African port.

* 22/6/40: the Elgo was a Swedish freighter going from Tunis

to Sfax.

– Small French steamer Cheik (1,000 tons) sunk by sub Scire.

* 10/7/40: torpedoed by error on the Marseille-Alger route;

13 men missing. I suppose this does not

count as a legitimate sinking since the Franco-Italian armistice was already in

effect. The Italian sub rescued the survivors,

later repatriated to Corsica on board Italian minesweeper Argo.

* Other reported incidents involving Vichy French vessels in

the Mediterranean:

* Note: there could be more cases, but the attacker often

remains unidentified, or no damage was done.

* 13/9/40: a French convoy (11 merchantmen) drifted a bit

from its Bone-Marseille route and entered an Italian minefield near San Pietro

(Sardinia). The liner Cap Tourane struck

a mine first but kept afloat; 3 dead and 17 missing among military

passengers. The freighter Cassidaigne,

coming to help, then struck a mine too and sank rapidly. Finally, the freighter Ginette-Leborgne,

bringing up the rear of the convoy, suffered the same fate. No other casualties are reported.

* 28/7/41: Tunisian sail-ship Sidi Fredg attacked by 3

Italian seaplanes (somewhere between Nabeul and Korba); 2 wounded, ship

abandoned, later retrieved.

UK Losses in the Mediterranean

The UK losses in the Mediterranean for the duration of the

war were 41 submarines and 175 surface warships of all types. So, the impact of

Italian Navy and Italian/German aircraft was not small.

Coincidently the surface ships lost in the Atlantic also

amounted to 175 of all types (the Japanese accounted for another 50).

I do not denigrate the Italian war effort, but emphasise

that their surface combats between Warships (not MTB’s etc) could have been

more effective.

Figures are from “Standard of Power”, Dan Van Der

Vat.

Italian Chances

The Italian pre-war doctrine was very similar to that of the

USN. Their ships were designed to fight long-range (20,000 yards plus) gunnery

duels. The Italians practiced this doctrine almost exclusively. Thus, their

ships were designed with extremely long, high-velocity guns to give great

range. However, this gave the guns extremely short barrel lives for modern

designs, as much as a third of their foes. Barrel life has a significant effect

on accuracy, especially if the individual guns have different wear. Further,

the Italians had poor production standards in both shells (weight) and powder.

This further exacerbated gunnery calculations. All this was then combined with

optics that were not designed with good water resistance – but the same optics

were also usually mounted too low and were, thus, extremely wet! Taken in

concert, the resulting gunfire, under wartime conditions, produced patterns

with great variations in dispersion, which greatly affected the chance to hit, especially

at long range! Thus, the Italians went to war with a doctrine that was all but

assured to fail – but they did not know it! Of course, neither did anybody

else!

Another serious factor was the fact that the new Littorio

class battleships, which had a new and marvelous torpedo defense system in

theory, found that it was seriously flawed in actual practice. Thus, their

newest and most powerful warships were prone to suffering severe underwater damage

at inopportune times.

One the Italians became aware of these two serious issues,

it was 1941, and they found themselves with a navy that was designed to fight

in a fashion that it could not, really, succeed at. Add a severe fuel crunch

into the mix, and you can see why the Italians ended up relying on small craft.

#

“For Vittorio Balbo Bertone Di Sambuy [Mach Pari tra due grande flotte Mediterraneo,

1940-1942], the naval war was a “match pari”– a draw– between

the British and the Italians, and this seems a reasonable judgement. While Supermarina (1) certainly made errors,

and cooperation with the air force was not perfect, in the spring of 1941, the

RMI understood the need to occupy Tunisia, and it pressed for the seizure of

Malta in 1941 and 1942. Had Supermarina been able to use Tunis and Bizerte, and

had the Germans aided their ally as generously as the United States did theirs

(2), the war would probably have run a different course. Certainly, the Italian navy cannot be blamed

for the failure of Hitler and OKW to appreciate the importance of the

Mediterranean, and it is clear that the British held crucial technological and

intelligence advantages in their struggle with Italy (3).

Yet Italy was

the major Axis player in the Mediterranean, and it was the Italian navy and air

force, with only sporadic help from their German ally, that stymied the British

navy and air force for most of the thirty-nine months that Italy was a

belligerent. To pretend otherwise is to

raise propaganda to the level of reasoned analysis, just as to explain the

RMI’s defeat by culling criticism regarding Italian competence from German and

British sources is to credit racist prejudice as objective observation. All

navies made mistakes, and all navies had personnel who were bureaucratic,

marginally competent, prone to error, and individually unpalatable, but to

criticize Iachino as cowardly for not entering British smokescreens while

praising Cunningham’s decisions to avoid Italian smokescreens as prudent is to

apply a pernicious double standard. If Vian is to be praised for avoiding

Iachino in the two battles of Sirte Gulf, then Campioni should also be praised

for avoiding Cunningham and Somerville at Punta Stilo and Cape Teulada

(4). And if so much is made of the few

convoys that managed to reach Malta, much more should be made of the many that

kept the Axis war effort in Africa alive by repeatedly braving attack by

aircraft, submarine, and surface vessel.

If doomed by its technical weaknesses and Ultra, the Italian navy still

fought a tenacious, and gallant, war; and if it did not win its war, it avoided

defeat for thirty-nine long, frustrating months.”

(1)

Supermarina was naval command, the central headquarters for the RMI.

(2) In the

previous paragraph, Sadkovich had mentioned that “between 1940 and 1942,

the United States supplied Britain with over 11,000 aircraft, far more than the

few squadrons of Ju.87s sold Italy by Germany.”

(3) the chief

intelligence advantage was of course Ultra, which from the spring of 1941

proved invaluable in locating and harassing Italian convoys to North Africa.

(4)

Sadkovich’s point here is that at Punta da Stilo and Cape Teulada the Italians

were the inferior force and should be given credit for being able to disengage

more or less intact. An assertion open

to argument, perhaps, but not too much of a stretch. At Punta da Stilo (Jul ’40) Cunningham had

three 15-inch gun battleships (Warspite, Malaya, Royal Sovereign) plus a

carrier (Eagle), while Campioni had the two small battleships Cesare and Cavour

(also the oldest in the Italian navy), which had 12.6-inch guns. The Italians did possess a considerable

advantage in cruisers– six heavy and a dozen light compared to five cruisers

total for the British– but in a long-range gun battle, which was essentially

what

Punta da Stilo was, the characterization of Campioni as

being at a disadvantage is pretty accurate.

At Cape Teulada (Nov ’40) the British had two forces which managed to

unite, giving them the battleship Ramillies, battlecruiser Renown (both with

15-inch guns), carrier Ark Royal, five large cruisers, and ten destroyers.

Campioni had battleships Vittorio Veneto (15-in) and Cesare (12.6-in), six

heavy cruisers, and 14 destroyers. So again,

it is not unreasonable to say the advantage lay with the British. Furthermore, Campioni was under very

restrictive orders—he was no to move beyond the range of land-based air cover

from Sardinia, and he was not to risk what remained of the Italian fleet (this

encounter occurred less than three weeks after the raid on Taranto) unless he

had a clear superiority. Personally, although there is much to be said about

the Italians in these two encounters–for starters, they did come out and face

arguably superior British battle fleets on both occasions, something their

critics frequently say they were too “afraid” to do, even when they

had an advantage that was definitely lacking in these examples–I would choose

as the Italian counterpart to the escapes of Vian at the two Sirte battles

(albeit on a smaller scale) the incident in May 1941 wherein the Italian

destroyer escort Sagitario, escorting 30 small vessels carrying German mountain

troops to Crete, held off a British force of five cruisers and three

destroyers, and saved the convoy.

James Sadkovich – The Italian Navy in World War II

This revisionist history convincingly argues that the Regia

Marina Italiana (the Royal Italian Navy) has been neglected and maligned in

assessments of its contributions to the Axis effort in World War II. After all,

Italy was the major Axis player in the Mediterranean, and it was the Italian

navy and air force, with only sporadic help from their German ally, that

stymied the British navy and air force for most of the thirty-nine months that

Italy was a belligerent. It was the Royal Italian Navy that provided the many

convoys that kept the Axis war effort in Africa alive by repeatedly braving attack

by aircraft, submarine, and surface vessels. If doomed by its own technical

weaknesses and Ultra (the top-secret British decoding device), the Italian navy

still fought a tenacious and gallant war; and if it did not win that war, it

avoided defeat for thirty-nine, long, frustrating months.

James Sandkovich: The Italian Navy in World War Ii, ed. Westport. 1994 (In Rome, at the Ufficio Storico della Marina Militare, Mr.Sandkovich epic activity looking for documents which were used for this very documented work is still a legend. He arrived to buy a personal Xerox machine to copy the various files he needed without having so to wait for the official copy service and presented it at the Ufficio Storico – where they consider it quite a monument in loving memory – after a year of continuous activity, almost night and day).

Jack Greene and Alessandro Massignani, The Naval War in the Mediterranean 1940-1943, July 15, 2011 Updated and Revised.

This was the first [1998] English-language account of the

naval war to take advantage of the research in all languages to provide a

comprehensive record of fighting in the Mediterranean during World War II. Far

more than an operational history, it explains why the various warship classes

were built and employed, the role of the Italian Air Force at sea, the

successes of German planes and U-boats, the importance of the battle of Malta,

and the distrustful relationship between the Italians and Germans.

Period photographs and detailed maps illustrate the

realities of war at sea and provide a clear visual record of the war’s key

events in the Mediterranean theater. With its in-depth background information,

exhaustive research, and fascinating narrative, this book is essential reading

for those interested in World War II.

Marc’Antonio Bragadin, The Italian Navy in World War II, Annapolis 1957 (It is dated but is the only one which can give you the right idea of what were the actual opinions at Supermarina – The Royal Italian Navy H.Q. – during the war)

Cdr. Junio Valerio Borghese, Sea Devils, Chicago 1954, reprinted 2009 by the Naval Institute Press.

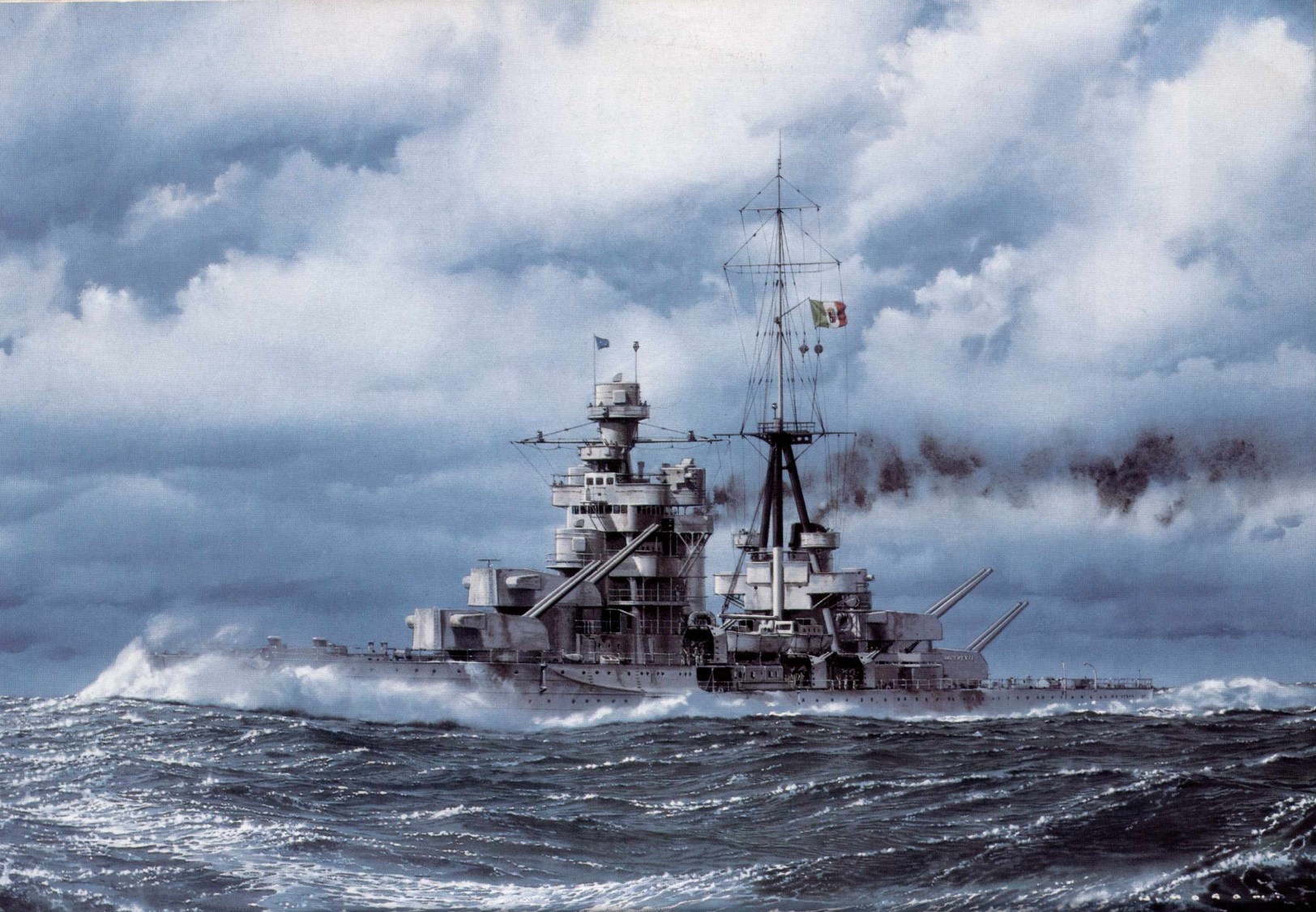

Erminio Bagnasco and Mark Grossman, Regia marina, Italian battleships of World War Two ed. Pictorial Histories Publ. Co. Missolula, Montana (good photos, excellent drawings and a concise but authoritative text); Erminio Bagnasco is also the author of “Submarines of World War Two”, ed. U.S. Naval Institute (there’s a German version too)

Aldo Fraccaroli, Italian Warship of World War Two, ed. Ian Allan, London, 1967 (a precious pocket book with the right description and data of all the Italian Warships of the last world war).

A.Santoni/F.Mattesini “La partecipazione tedesca alla guerra aeronavale nel Mediterraneo (1940-1945)”

Though about the Germans, could perhaps be useful for

contested hits. The authors wrote it (25 years ago) to prove that, compared

with the Germans’, the Italian Navy and Air Force achievements in the

Mediterranean War were poor: this against some Italian authors who

over-estimated or over-exalted them, not for anti-national feelings (btw

Santoni was teacher of Naval History at the Italian Navy’s Naval Academy).

G. Giorgerini “Uomini sul fondo” and “La Guerra Italiana sul mare”.

Giorgerini’s first book is a history of the Italian Navy

submarine branch (a good work, very objective if not even a little bit too

severe with our submariners in some judgements), the other one is a general

overview of the Italian Navy’s WWII (the book is recent and, well researched, a

good work too).

The Rivista Marittima (the Italian Naval staff monthly since

1868) has got, at the end of its various articles a summary in English, German,

French and Spanish. It’available on the web at

http://www.marina.difesa.it/rivista/index.htm while the e-mail is maririvista@marina.difesa.it

and the address is: Via dell’Acqua Traversa 151 00135 ROMA.

You may have the 11 numbers of the year and the 12 “supplementi”

(separate books inclusive of the service).

With a bit of will and a good dictionary (The Associazione

Navimodellisti Bolognesi, C.P. 976 40100 Bologna, may let you have, with their

catalogue formed by more than 2.200 drawings of ships, weapons and boats based

on the original projects of the Italian ships since XIX to XXI century a

concise but very useful technical Naval dictionary in English, German and

French) Italian language is not a too much difficult obstacle for naval matters

and it may give you quite a lot of surprises.