The Phoenicians were the first to build proper ships and to

brave the rough waters of the Atlantic.

To be sure, the Minoans before them traded with great vigor

and defended their Mediterranean trade routes with swift and vicious naval

force. Their ships—built with tools of sharp-edged bronze—were elegant and

strong: they were made of cypress trees, sawn in half and lapped together, with

white-painted and sized linen stretched across the planks, and with a sail

suspended from a mast of oak, and oars to supplement their speed. But they

worked only by day, and they voyaged only between the islands within a few

days’ sailing of Crete; never once did any Minoan dare venture beyond the

Pillars of Hercules, into the crashing waves of the Sea of Perpetual Gloom.

The Minoans, like most of their rival thalassocracies,

accepted without demur the legends that enfolded the Atlantic, the stories and

the sagas that conspired to keep even the boldest away. The waters beyond the

Pillars, beyond the known world, beyond what the Greeks called the oekumen, the

inhabited earth, were simply too fantastic and frightful to even think of

braving. There might have been some engaging marvels: close inshore, the

Gardens of the Hesperides, and somewhat farther beyond, that greatest of all

Greek philosophical wonderlands, Atlantis. But otherwise the ocean was a place

wreathed in terror: I can find no way whatever of getting out of this gray

surf, Odysseus might well have complained, no way out of this gray sea. The

winds howled too fiercely, the storms blew up without warning, the waves were

of a scale and ferocity never seen in the Mediterranean.

Nevertheless, the relatively peaceable inland sea of the

classical world was to prove a training ground, a nursery school, for those

sailors who in time, and as an inevitable part of human progress, would prove

infinitely more daring and commercially ambitious than the Minoans. At just

about the time that Santorini erupted and, as many believe, gave the final

fatal blow to Minoan ambitions, so the more mercantile of the Levantines awoke.

From their sliver of coastal land—a sliver that, in time, would become Lebanon,

Palestine, and Israel, and can be described as a land with an innate tendency

toward ambition—the big Phoenician ships ventured out and sailed westward,

trading, battling, dominating.

When they came to the Pillars of Hercules, some time around

the seventh century B.C., they, unlike all of their predecessors, decided not

to stop. Their captains, no doubt bold men and true, decided to sail right

through, into the onrushing waves and storms, and see before all other men just

what lay beyond.

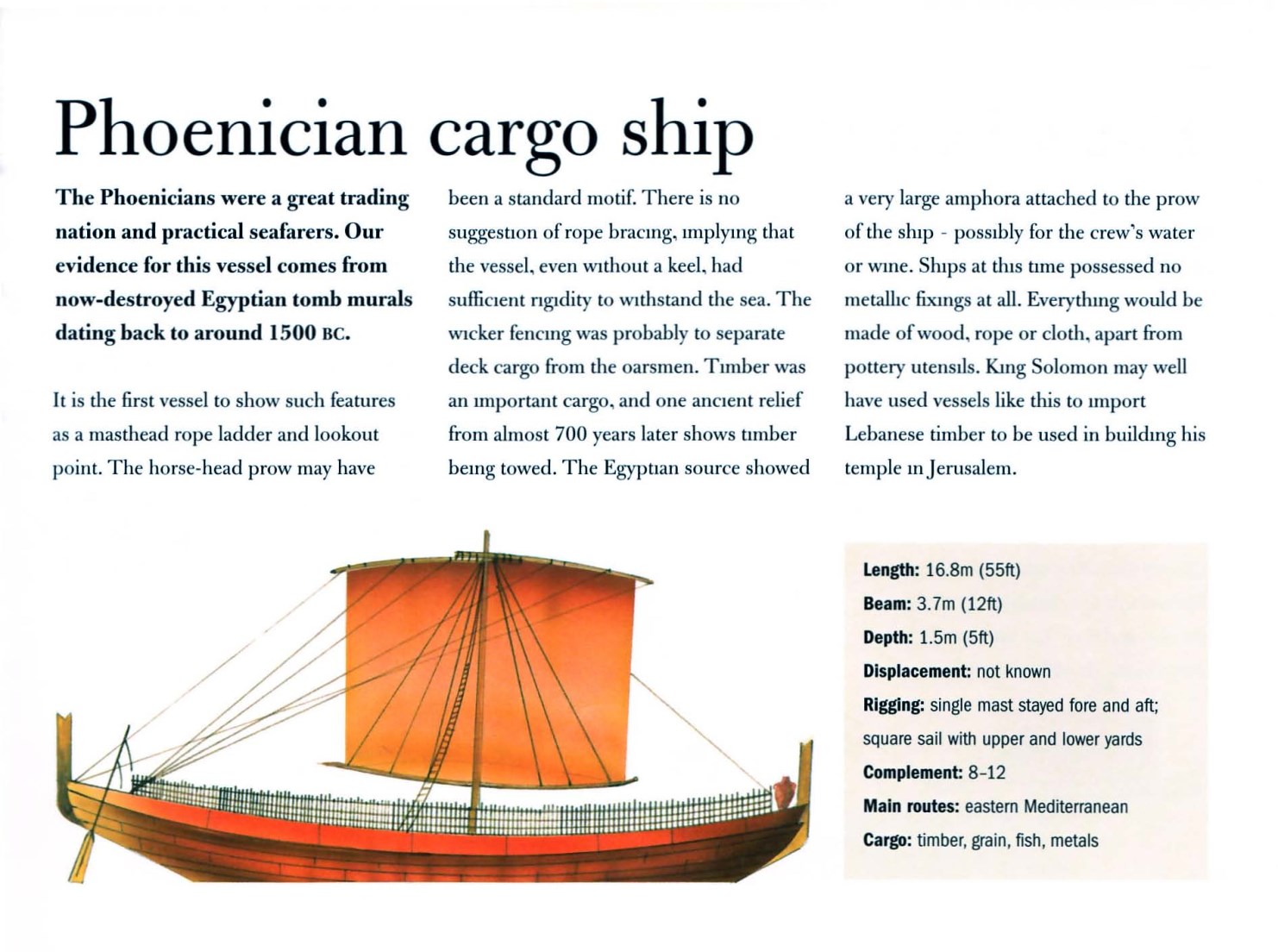

The men from the port of Tyre appear to have been the first

to do so. Their boats, broad-beamed, sickle-shaped “round ships” or galloi—so

called because of the sinuous fat curves of the hulls, and often with two sails

suspended from hefty masts, one at midships and one close to the forepeak—were

made of locally felled and surprisingly skillfully machined cedar planks, fixed

throughout with mortise and tenon joints and sealed with tar. Most of the

long-haul vessels from Tyre, Byblos, and Sidon had oarsmen, too—seven on each

side for the smaller trading vessels, double banks of thirteen on either side

of the larger ships, which gave them a formidable accelerative edge. Their

decorations were grand and often deliberately intimidating—enormous painted

eyes on the prow, many-toothed dragons and roaring tigers tipped with metal

ram-blades, in contrast to the ample-bosomed wenches later beloved by Western

sailors.

Phoenician ships were built for business. The famous Bronze

Age wreck discovered at Uluburun in southern Turkey by a sponge diver in 1982

(and which, while not definitely Phoenician, was certainly typical of the

period) displayed both the magnificent choice of trade goods available in the

Mediterranean and the vast range of journeys to be undertaken. The crew on this

particular voyage had evidently taken her to Egypt, to Cyprus, to Crete, to the

mainland of Greece, and possibly even as far as Spain. When they sank,

presumably when the cargo shifted in a sudden storm, the holds of the

forty-five-foot-long galloi contained a bewildering and fatally heavy amassment

of delights, far more than John Masefield could ever have fancied. There were

ingots of copper and tin, blue glass and ebony, amber, ostrich eggs, an Italian

sword, a Bulgarian axe, figs, pomegranates, a gold scarab with the image of

Nefertiti, a set of bronze tools that most probably belonged to the ship’s

carpenter, a ton of terebinth resin, hosts of jugs and vases and Greek storage

jars known as pithoi, silver and gold earrings, innumerable lamps, and a large

cache of hippopotamus ivory.

The possibility that the Uluburun ship journeyed as far as

Spain suggests the traders’ ultimate navigational ambitions. The forty ingots

of tin included in the cargo hints at their commercial motive. Tin was an

essential component of bronze, and since the introduction of metal coinage in

the seventh century B.C., the demand for it had vastly increased. It was known

anecdotally to the Levantines that alluvial tin was to be found in several of

the rivers that cascaded down from the hills of central southern Spain—the

Guadalquivir and the Guadalete most notably, but also the Tinto, the Odiel, and

the Guadiana—and so the Phoenicians, at around this time, decided to move, and

disregard the legendary warnings. For them, with the limited knowledge they had

and the jeremiads on daily offer from the seers and priests, it was as

audacious as attempting to travel into outer space: full of risk, and with

uncertain rewards.

And so, traveling in convoy for safety and comfort, the

first brave sailors passed beneath the wrathful brows of the rock

pillars—Gibraltar to the north and Jebel Musa to the south—made their halting

way, without apparent incident, along the Iberian coastline, and finding

matters more congenial than they imagined—for they were in sight of land all

the time, and did not venture into the farther deep—they then set up the

oceanic trading stations they would occupy for the next four centuries. The

first was at Gades, today’s Cádiz; the second was Tartessus, long lost today,

possibly mentioned in the Bible as Tharshish, and by Aristophanes for the

quality of the local lampreys, but believed to be a little farther north than

Gades, along the Spanish Atlantic coast at Huelva.

It was from these two stations that the sailors of the

Phoenician merchant marine began to perfect their big-ocean sailing techniques.

It was from here that they first embarked on the long and dangerous voyages

that would become precedents for the following two thousand years of the

oceanic exploration of these parts.

They came first for the tin. But while this trade

flourished, prompting the merchantmen to sail to Brittany and Cornwall and even

perhaps beyond, it was their discovery of the beautiful murex snails that took

them far beyond the shores of their imagination.

The magic of murex had been discovered seven hundred years

before, by the Minoans, who discerned that, with time and trouble, the mollusks

could be made to secrete large quantities of a rich and indelible

purple-crimson dye—of a color so memorable the Minoan aristocracy promptly

decided to dress in clothes colored with it. The color was costly, and there

were laws that banned its use by the lower classes. The murex dye swiftly

became—for the Minoans, for the Phoenicians, and most notably of all, for the

Romans—the most prized color of imperial authority. One was born to the purple:

only one so clad could be part of the vast engine work of Roman rule, or as the

Oxford English Dictionary has it, of the “emperors, senior magistrates,

senators and members of the equestrian class of Ancient Rome.”

By the seventh century B.C., the seaborne Phoenicians were

venturing out from their two Spanish entrepôts, searching for the mollusks that

excreted this dye. They found little evidence of it in their searches to the

north, along the Spanish coast; but once they headed southward, hugging the low

sandy cliffs of the northern corner of Africa, and as the waters warmed, they

found murex colonies in abundance. As they explored, so they sheltered their

ships in likely-looking harbors along the way—first in a town they built and

called Lixus, close to Tangier and in the foothills of the Rif: there remains a

poorly maintained mosaic there of the sea god Oceanus, apparently laid by the

Greeks.

Then they moved on south and found goods to trade in an

estuary close to today’s Rabat. They left soldiers and encampments at

still-flourishing coastal towns like Azemmour, and then, in boats with high and

exaggerated prows and sterns, decorated with horses’ heads and known as hippoi,

they pressed farther and farther from home, coming eventually to the islands

that would be named Mogador. Here the gastropods were to be found in suitably

vast quantities. And so this pair of islands, sheltering the estuary of the

river named the Oued Ksob, is probably as far south as they went, and this is

where their murex trade commenced with a dominating vengeance.

What are now known as Les Îles Purpuraires, bound inside a

foaming vortex of tide rips, lie in the middle of the harbor of what is now the

tidy Moroccan jewel of Essaouira. This town is now best known for its gigantic

eighteenth-century seaside ramparts, properly fortified with breastworks and

embrasures, spiked bastions, and rows of black cannon, and which enclose a

handsome cloistered medina. The walkways on top of the curtain walls are the

perfect place to watch the ever-crashing surf from the Atlantic rollers,

especially as the sun goes down over the sea. The Phoenicians found that the

snails gathered in the thousands there, in rock crevices, and they scooped them

up in weighted and baited baskets. Extracting the dye—known chemically as

6.6′-dibromoindigo, and released by the animals as a defense mechanism—was

rather less easy, the process always kept secret. The animal’s tincture vein

had to be removed and boiled up in lead basins, and it would take many

thousands of snails to produce sufficient purple to dye a single garment. It

was traded, and the trade was tightly controlled, from the home port of the

sailors who harvested it: Tyre. For a thousand years, genuine Tyrian purple was

worth, ounce for ounce, as much as twenty times the price of gold.

The Phoenicians’ now-proven aptitude for sailing the North

African coast was to be the key that unlocked the Atlantic for all time. The

fear of the great unknown waters beyond the Pillars of Hercules swiftly

dissipated. Before long a viewer perched high on the limestone crags of

Gibraltar or Jebel Musa would be able spy other craft, from other nations,

European or North African or Levantine, passing from the still blue waters of

the Mediterranean into the gray waves of the Atlantic—timidly at first maybe,

but soon bold and undaunted, just as the Phoenicians had been.

“Multi pertransibunt, et augebitur scientia” was a phrase

from the Book of Daniel that would be inscribed beneath a fanciful

illustration, engraved on the title page of a book by Sir Francis Bacon, of a

galleon passing outbound, between the Pillars, shattering the comforts and

securities of old. “Many will pass through, and their knowledge will become

ever greater,” it is probably best translated—and it was thanks to the

purple-veined gastropods and the Phoenicians who were brave enough to seek them

out that such a sentiment, with its implication that learning comes only from

the taking of chances and risk, would become steadily more true. It was a

sentiment born at the entrance to the Atlantic Ocean.