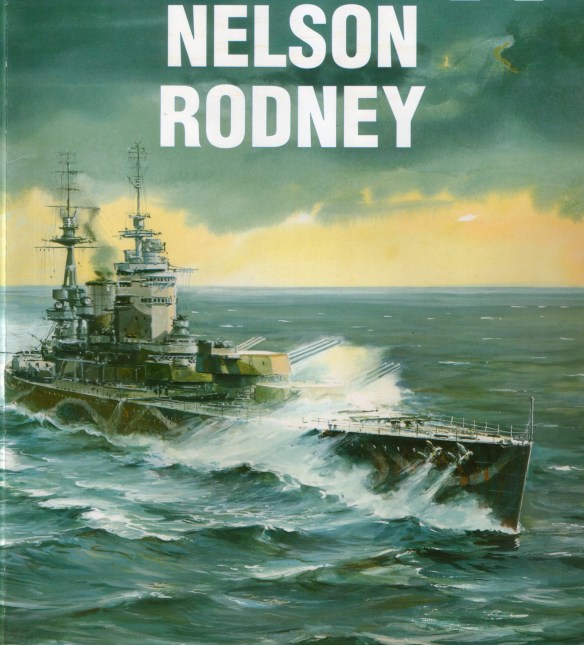

Because the latest U. S. and Japanese battleships already mounted

16-inch guns, the Washington Treaty permitted the British to construct two capital

ships, Nelson and Rodney, the only battleships in any navy designed and

completed during the 1920s, and the only Royal Navy battleships ever to mount

16-inch guns. These were strange-looking warships, mounting all main guns

forward to consolidate armor and thus keep under the treaty’s tonnage limits.

(The British referred to them facetiously as “cherry trees . . . cut down

by Washington”).

Thursday 17 December 1925 dawned cold and damp, one of those

grey mornings when even the most robust and sturdy shipyard worker seemed

dejected and miserable. But there was a good reason for high spirits because it

was a very special day for the Birkenhead shipyard and a huge crowd had wrapped

themselves up in their warmest clothing and gathered in and around the yard to

await the arrival of HRH Princess Mary and her husband Viscount Lascelles to

perform the naming ceremony of one of the most powerful battleships ever

constructed in a British yard. Indeed, the people of Liverpool and the little

town of Birkenhead, and Messrs Cammell Laird Shipbuilding and Engineering Works

were justly proud of the occasion. Not only had they brought a new concept in warship

design to the launching stage, but they were witnessing the construction of one

of the few British battleships to be laid down during the inter-war years. The

very existence of such a vessel during the depression was something of a

miracle; she was being built under the shadow of severe naval restrictions

which governed displacements and gun sizes. The general public saw the ship as

something of a compromise and hardly knew what to expect because of the

continuous agitation in the Press during the last few years since the

Washington Naval Treaty of 1921, whereby Britain had agreed to reduce the size

of her fleet, abandoning the `two power standard’ and aligning herself

numerically with the USA. In 1921 Britain had laid down four giant 48,000-ton

battlecruisers of which this ship should have been one, but lengthy

negotiations had reduced their size by more than 15,000 tons, and only two

instead if four were allowed to compensate for the latest battleships building

in Japan and the USA at that time.

At approximately 10.15 a. m. on that December morning HRH

Princess Mary and her husband entered the shipyard to be met by The Right Hon

Earl of Derby, KG, GCB, GCVO, and a very vociferous crowd. The Royal party were

introduced to Mr W. L. Hichens (Chairman) and Mr R. S. Johnson (Managing

Director) before making their way to the firm’s main offices.

At precisely 10.40 a. m. Her Royal Highness left the offices

and made her way to the launching platform where the religious ceremony was

then held. At exactly 11.15 a. m., in a moment of hush, a quiet voice called,

`I name this ship Rodney, and God bless all who sail in her’, and the lever was

pulled to release the christening fluid over the bows of the great ship. Thus

the mighty Rodney slid calmly and majestically down the slipway for about fifty

feet before entering the cold water of the River Mersey.

In the coming months, she and her sister (Nelson, which had

been launched a few months earlier in September) would be fitting out and

taking shape, and the media would get their first look at what had been one of

the most controversial designs of the inter-war years. Indeed, they were to

wonder whether the two ships would be worth £7,000,000 each, when the latest,

and larger, Hood had only set them back a little over £6,000,000. With

hindsight, however, it can be said that Nelson and Rodney proved to be two of

the most powerful 16in-gunned battleships ever built, and the sterling work

they were about to do during the coming war (1939-45) would more than justify

their building; in fact, at the outbreak of war, they were the latest

battleships that the Royal Navy possessed.

Design

During the period 1919 to 1921, a considerable number of

alternative capital ship designs, embodying 1914-18 experience, especially the

lessons of Jutland and the recommendations of the Post-War Questions Committee,

were prepared and considered by the Admiralty, and in 1921, when the large

programme in hand in the USA and Japan necessitated a resumption of British

capital ship construction, a battlecruiser type of 47,540 tons was chosen. The

latest ship to complement the Royal Navy’s fleet at that time (1920) was the

large battlecruiser Hood, and although she had been constructed without regard

to the many lessons learnt at Jutland, her general design and layout was

naturally followed (`K’, `K2′ and `K3′).

Following these sketch designs, there was a serious

investigation into the construction of one of the largest and most powerful

battleships built to date (`13′), but although it reached sketch stage and

gained some Board approval, the Constructor’s department saw it as far too large

and radical at that time. In 1920, however, the NID informed their Lordships

that both Japan and the USA would probably construct vessels of about 48,000

tons armed with 18in guns in the near future, and it was reluctantly agreed

that the Royal Navy would have to follow suit to meet any threat. It was

realized, however, that ships of such a size would introduce severe problems

not only for designers, but in docking accommodation as well.

During the next few months various designs were prepared for

both battleships and battlecruisers, but unfortunately most of the information

(ship’s covers) concerning the battleships has been mislaid, only the

battlecruiser layouts being available (variations of `K’, `L’, `M’ and `N’

Designs were shown). In December 1920 it was decided that the sketches `G3′ and

`H3′ (battlecruisers) should be investigated further, but with modifications on

`G3′ so as to include extra armour protection to the deck area. After viewing

the modified `G3′ layout, the Board accepted it in principle and in February

1921 asked for confirmation and further preparation on four ships of such a

calibre. The DNC (d’Eyncourt) particularly approved of the modified G3 and

wrote to the First Sea Lord on 23 March 1921 pointing out the salient features:

The main armament consists of nine 16in guns in three

turrets with 40 degrees elevation. Two pairs forward and one amidships. The

latter cannot fire right astern.

War experience, and our recently acquired knowledge of

German and United States turrets have been carefully considered in connection

with the main armament; the protection and flashtightness is very complete.

Secondary armament consists of sixteen 6in in eight turrets,

arranged so that supply from magazines and shell rooms is very direct, but is

provided with breaks and other safeguards to prevent flash passing down into

magazines. AA consists of six 4.7in high-angle guns, and mountings embody the

latest highangle ideas as recommenced by Naval High Angle Gunnery Committee.

Armament controls are a special feature. An erection forward

supports the main director control tower, two secondary directors and the

high-angle directors, and calculating positions are free from any smoke

interference. Aeroplane hangars may be considered as a permanent feature but a

decision is pending.

Main armament has been concentrated in the centre of the

ship in order that the heavy horizontal and vertical armour required to protect

it may be a minimum, and also that the magazines may be placed in the widest

part of the ship, and the underwater protection be the best that can be

afforded. Over this central citadel a 14in belt is arranged, and resting on the

belt is a deck of 8in on the flat and 9in on the slopes. These thicknesses and

angles have been carefully calculated after consideration to oblique attack

results with the latest type of shell. Abaft the central citadel a sloping 12in

belt and 4in deck are provided over machinery spaces.

The belt extends over the aft 6in magazine, and here the

deck is increased to 7in. Abaft the citadel a thick deck of 5in is provided

over the steering gear.

Barbettes are 14in and turrets and 17in on the face with 8in

roofs.

Underwater experience is based on Chatham Float tests and

embodies the principle of the bulge as fitted to the Hood. The side underwater

protection is designed to withstand a charge of 750lb of explosive.

Protection against mines is afforded by a double-bottom of

7ft deep.

By sloping the main belt outwards, not only is the virtual

thickness increased, but protection is provided against attack by

distant-controlled boats containing large explosives. In order that the

stability of the vessel may be adequate, the triangular space between side and

armour will be filled with light tubes. Calculations show that the whole of

this structure would have to be completely blown away before the ship would

lose stability.

Although never wanting ships with such mastodon proportions,

on accepting the `G3′ design and the battleship version `N3′, the Royal Navy

had accomplished what it set out to do, and that was completely to outclass any

foreign opposition for at least five years ahead. The design was far ahead of

its time and showed features which even matched the Japanese giants of the

Yamato class constructed in 1941. Indeed, it may be that the `G3′ plans were

carefully considered by the Japanese when their two ships were under

construction because they certainly reflected many qualities of the early 1921

British design.

With all major maritime powers building along the same lines

it was only too obvious that it would be but a matter of time before the design

was overshadowed by a vessel grossly out of proportion to requirements, with

everyone else being forced to follow. The political implications were too

complex to be discussed here, but the result ended in a Naval treaty called for

by the USA and it would include Great Britain, Japan, Italy and France. An

agreement was reached whereby there would be a battleship holiday for the next

ten years. New ships could only be constructed after existing ships had reached

the age of 20 years, and new construction was limited to 35,000 tons and

calibres reduced to 16in guns rather than the 18in being prepared at that time.

Dozens of older (in Britain’s case not so old) battleships went to the

scrapyard.

Contracts for the British `G3′ class (four) had been under

way for some time and when in February 1922 letters had to be sent out to the

four yards involved, stating that the ships were cancelled, it came as a bitter

blow to an already flagging industry during the depression.

To offset the retention of the West Virginia and Nagato

classes by the United States and Japan respectively, which had been too far

advanced to scrap, Great Britain authorized under the Treaty two new designs to

comply with the severe limitations that had been imposed on construction.

As early as November 1921, when it became probable that the

four `G3′ group vessels were to be scrapped, the Constructor’s Department was

asked to prepare fresh layouts within the limits of the treaty, but was asked

to include any of the G3’s features where possible. The first three sketches

(`F1′, `F2′, `F3′) featured 15in guns because the department thought that no

suitable 16in-gunned design could be acquired on such a limited displacement,

but it would appear that the designs received little consideration because both

the USA and Japan now had 16in-gunned battleships (see tables). In January 1922

further proposals were forwarded showing a reduced edition of the `G3′ but

retaining many of its qualities (`O3′, `P3′ and `Q3′) with a speed of 23 knots.

The Controller asked for the designs to be fully worked out,

and it was proposed to Constructor E. L. Attwood that dimensions be 710ft by

102ft (waterline) by 30ft, and that SHP sufficient to reach 23/24 knots would

be needed. The main armament would be the same as in the `G3’s (16in), but

armour plating would be severely thinned down from that design. In order that the

legend weight, as defined by the Washington Treaty, should come within the

35,000 tons limit, the utmost economy was called for, and no Board margin was

possible for any weights added during construction. In September 1922 the final

design was accepted (modified `03′) and it embodied all the essential features

demanded:

1. High freeboard and good seakeeping qualities, these being

regarded as essential.

2. Armament as in the cancelled battlecruisers (`G3′).

3. Armouring generally similar to that of the battlecruisers,

and concentrated over magazines, machinery and gun positions on the `all or

nothing’ principle.

4. Speed equal to or higher than contemporary foreign

battleships.

Although having the same main armament and turret

arrangement as the cancelled battlecruisers (whose guns and mounts were

utilized to a certain extent) and resembling them in certain outward

characteristics, Nelson and Rodney were in no sense merely a reduced edition of

those ships, but constituted an entirely distinct `battleship’ type,

representing the nearest approach that could be obtained, within the limits, to

the 48,000- ton plan previously proposed. The battlecruiser design was stated

to have constituted a reply to Naval Staff Requirements for an `ideal

battlecruiser’; Nelson and Rodney, on the other hand, represented the best that

could be done, within treaty limitations, towards meeting the demand for an

`ideal battleship’.

The influence of the Treaty restrictions on the new ships

was considerable, as it was necessary, for the first time, to work to an

absolute displacement limit which could not be exceeded, but which had to be

approached as closely as possible in order to secure maximum value. The history

of these two ships, then, is a complex one, but when laid out in tabular form

it seems straightforward:

1. At the conclusion of the 1914-18 war, investigations were

conducted into capital ship design to incorporate the lessons learnt at Jutland

in particular.

2. Battlecruiser design with legend displacement of 48,000

tons was approved by the Board of Admiralty on 12 August 1921.

3. Orders were placed for four ships on 26 October 1921, but

cancelled on 13 February 1922 under Washington Naval Treaty’s directive not to

exceed 35,000 tons. 4. Investigations into designs for a 35,000-ton battleship

resulted in sketch `03′ (modified) being accepted by the Board, and became

Nelson and Rodney. 5. The Washington Treaty’s 35,000-ton limit led to

development of better quality steel.

6. No further capital ships to be built from 12 November

1921 except Nelson and Rodney.

7. General armour and protection affected (reduction from

`G3′) to save weight.

8. The armour citadel was 384ft by 14in abreast 16in

magazines, sloped at 70° and was so arranged inside the hull that the slope

produced downwards did not meet protection bulkheads. Each belt of armour was

keyed, and individual plates were made as large as possible with heavy bars

fitted behind the butts. Chock castings housing the lower edge of armour also

directed fragments of bursting shells away from the belt.

9: No new construction to be commenced until: United States

1931; Great Britain 1931; France 1927; Japan 1931; Italy 1927[a1] .

Armament

With the exception of the 16.25in gun mounted in the Benbow

and Sans Pareil classes, completed 1888 and 1891 respectively, Nelson and

Rodney were the first and only British battleships to have 16in BL guns in

triple-mounted turrets, which made them the most powerfully armed battleships

afloat. An experimental mounting had been produced by Messrs Armstrong and Co. and

fitted and satisfactorily tested in the monitor Lord Clive in February 1921 in

anticipation of their being fitted in the `G3′ group. When the `G3’s were

cancelled some £500,000 had been spent on them and it was only natural that the

money and results of the tests should be used in the new ships of the Nelson

class. Concentration of the entire main armament forward was unique at the time

of their building, and allowed a minimum length of armoured citadel with

maximum protection to gun positions and magazines, while the close grouping of

the turrets incidentally facilitated fire control. These advantages were

considered to outweigh the loss of tactical efficiency caused by the absence of

direct astern fire which at first was a much criticized feature; the design, in

this respect, subordinating tactical principles to severe pressures in

constructional requirements and weight saving. The arrangement was not repeated

after the Nelson pair, although it was later adopted by the French Navy in the

Dunkerque and Richelieu classes (laid down 1932-7 respectively). Although no

direct astern fire was provided, the superstructure was cut away and so

arranged as to allow `A’ and `B’ turrets rather large nominal arcs of fire,

bearing respectively to within 31° and 15° of the axial line astern.

The 16in gun was a high-velocity/lighter shell weapon, but

tests after completion showed that it was much inferior to the

low-velocity/heavy shell 15in gun which had proved itself an excellent piece

during the Great War. Nevertheless, the heavier weight of broadside did have

its compensations (6,790lb heavier than in Queen Elizabeth) and was not

equalled until 1941 when the US North Carolina entered service with a similar

armament.

Magazines and shell rooms were grouped together around the

revolving hoists, and the boilers were located abaft instead of before the

engine rooms so that the uptakes and funnel arrangement could be placed further

aft, with a view to minimizing smoke interference to the control positions on

top of the bridge structure. She was an improvement over previous designs, but,

as completed, the funnel proved to be too short, being appreciably lower than

the massive tower and its controls, especially steaming head to wind when the

tower produced considerable backdraught and the funnel gases caused severe

discomfort.

On trials, and during gunnery tests, it was found that when

the guns were fired at considerable angles abaft the beam, the structure and

personnel were affected by blast. In particular, `C’ turret, when fired abaft

the beam at full elevation was to cause severe problems, and special measures

would be needed when firing at these angles (see Captain’s report, elsewhere).

Many officers thought that the blast was too severe, and that the design was a

bad one, but when tests were carried out by HMS Excellent during the early gun

trials, there was a divergence of opinion.

Gun pressures on the bridge windows were recorded and showed

figures of 8½psi when bearing 120 degrees green or red, and it was suggested

that bridge personnel might possibly be moved to the conning tower when the

guns were firing at these angles. Constructor H. S. Pengelly was aboard Rodney

on 16 September 1927 and had this to say when making his report for their

Lordships:

During the firing of

`X’ and `B’ abaft the beam, I remained on the middle line at the after end of

the Admiral’s platform. The firing from `B’ was not uncomfortable, but there

was considerable shock when `X’ fired at 130 degrees or slightly less, but at

40 degrees of elevation. The shock was aggravated by one not knowing when to

expect fire, but apart from this point, it is understood that the blast

recorded at the slots on the Admiral’s platform were about 9lb psi and on the

Captain’s platform about 11lb psi. It was noted that 10 degrees more bearing

aft made all the difference to the effect experienced on the bridge.

The bridge structure

was, in itself, entirely satisfactory, and I was informed by the officers

occupying the main DCT forward, that this position was extremely satisfactory,

and they would have been ready, throughout the whole of the firing, to fire

again in 8 to 10

The only damage was on

the signal platform – 1 x 18in projector at the fore end – glass smashed, and

shutter of another broken.

On the Captain’s

bridge, four windows broken, a few voice pipes loose. On Admiral’s bridge, four

windows broken. Number of electric lights put out of action. General damage was

little, and the extra stiffening inboard after Nelson’s gun trials appear to

have functioned well.

They were the first British battleships to carry

anti-torpedo guns in turrets, which afforded, in addition to the better

protective area for gun crews, substantially wider horizontal and vertical arcs

of fire than the battery system of the preceding classes. On the protection

side, however, the secondary armament failed miserably because of the

restricted weights allowed in the ships, and the whole of the secondary

armament – turrets and barbettes – were practically unarmoured, with nothing

more than 1in high-tensile steel all over as a form of splinter shield.

The turrets were arranged in two compact groups, governed by

the same considerations of concentration to allow magazine grouping, as had

been the case with the main armament. There was some criticism of the close

grouping because a single hit might put the entire battery out of action on any

one side. They were located as far aft as practicable so as to minimize blast

effect from the after 16in guns when firing abaft the beam. Their higher

command (about 23ft against 19ft) meant that the fighting efficiency of these

guns in moderate or rough weather was materially better than that of the Queen

Elizabeth and Royal Sovereign classes, an advantage that was demonstrated

during fleet manoeuvres in March 1934 when units of all three classes operated

together in some of the worst weather ever experienced during practical battle

tests (the secondary guns of the QE and RS classes were seen to be completely

waterlogged and were of no use whatsoever).

The 24.5in torpedo armament was introduced in this class

(21in was the largest previously carried) even though there was a body of

opinion that expressed a wish to discontinue torpedo tubes in capital ships.

The tubes were not trained abeam, but angled forward to within about 10 degrees

of the axial line. To eliminate risk of serious flooding, the torpedo

compartments were located in a separate flat rather than a single flat as in

preceding classes, which was seen a serious fault in those early classes. The

torpedo control positions were located on the superstructure close before the

funnel.

Given that the design had been restricted in displacement,

the armament in general was more than adequate, but the triple mounting of the

16in guns was not viewed favourably in the Constructor’s Department, which

preferred twin mountings as in preceding classes – a well-tried and proven set

of equipment. The trouble seems to have been the extreme weight of the entire

triple mounting (1,500 tons approx.) which bore down too heavily on the flanges

of the roller path when the turret was being trained. As a result of this and

other small teething problems the guns or turrets never achieved the reputation

of the twin mounted 15in gun which, in hindsight, has been considered the best

combination that ever went to sea in a battleship. After new vertical rollers

had been fitted, and much experimentation on the 16in mountings, things did

improve, but they were never troublefree during prolonged firing.