Through the second half of 1420 Žižka had to engage in some

intra-Hussite fighting. The poorest people of Bohemia not only embraced the

teachings of Hus but carried them further into a millennial belief that a

completely equal society would bring about Christ’s second coming. The middle

class and minor aristocracy opposed this for economic more than religious

reasons, and Žižka depended on the city burghers (his own background) for the

majority of his support. Thus, the poor who rallied around the most radical

priests found themselves suppressed and ultimately defeated in battle. Some

survivors left for more radical settlements, but the bulk of the poor, both

rural and urban, realized that what progress they could make in advancing

themselves in any socioeconomic way was by following Žižka. The fortress town

of Tabor was still regarded as one of the more radical communities, but it was

controlled by the middle class. By early 1421 Žižka had solidified his position

as commander in chief of the Hussite forces, in and out of Tabor.

Early in 1421, Sigismund had withdrawn from Bohemia back to

Germany, leaving the Hussites time and opportunity to deal with their own

issues, and bringing an end to the first crusade. For the Hussites, the absence

of any crusaders gave them the chance to spread their own influence. Many towns

were attacked, with sieges lasting at times a few days and other times a few

months. It was during one of these sieges that Žižka suffered a significant

injury: during the siege of the town of Rabi, near the Hussite-held city of Tachov,

Žižka led the first assault and was hit in the face by an arrow. This took out

his second eye and almost killed him, but several weeks in Prague allowed him

to recover his health, though he was now blind. It mattered little: Žižka

fought some of his greatest battles and campaigns after he lost his second eye.

Although he could have sustained himself on his reputation alone, his talents

were undiminished. His reputation did indeed precede him, however. In late July

German forces from Meissen crossed the border to successfully relieve the

Hussite siege of Most. The Hussite Prague army was reconstituted a month later

with Žižka in command and marched back to face the leading elements of the

second crusade. When news arrived that Žižka was leading the Hussite force

toward them, even as he was still recovering from his wound, the German army

turned and went home rather than face him.

The second crusade consisted of larger forces than the

first; estimates range from 120,000 to 200,000. The crusaders had orders to

kill all Czechs but small children. The initial force marched east out of the

Upper Palatinate through Cheb on the way to Zatec, a Hussite stronghold. A

second force came out of Meissen in three prongs, attacking a number of towns

northwest of Prague before joining with the first army. Zatec was soon

invested, but held off six major assaults. Collapsing morale from the

crusaders’ failures and Hussite sallies were compounded by word on 2 October

that Žižka’s army was on its way. Again, that was all the Germans needed to

convince them to pack up and retreat. To make matters worse for them, a fire

broke out in their tent city just before they were ready to leave. The

defenders sallied out and inflicted serious damage on the already hurting

crusader force, leaving them with a total of some 2,000 dead. Worse still, this

defeat came even before Sigismund got his army moving, leaving the second

crusade in a less than hopeful state.

Kutná Hora and

Německý Brod

A third offensive from the south kept Žižka busy through the

autumn of 1421. During that time Sigismund was finally getting his offensive

under way. A Hungarian force of 60,000 (including 23,000 cavalry) marched into

Moravia under the command of Philip Scolari, an Italian mercenary general

better known by his nickname Pipo Spano; Sigismund joined him in late October

at the town of Jihlava on the Moravian-Bohemian border. Instead of immediately

marching for Kutná Hora to recover the mint and mines, Sigismund practiced his

normal hesitation and waited for reinforcements. This gave Žižka’s army of

12,000 time to reach the city first (on 9 December) and strengthen its

defenses. The imperial army also took twenty days to march the fifty miles from

Jihlava to Kutná Hora. Heymann describes the advance: “All the time [Sigismund’s]

Hungarians destroyed Czech villages, burned the men, mutilated the boys, raped

the women and girls. The behavior of his troops was so atrocious that not one

of the Czech chronicles which describes this invasion omits reference to it.”

Sigismund and Scolari arrived at Kutná Hora on December 21.

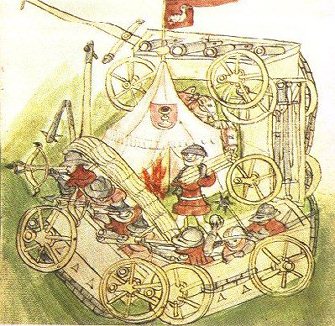

As the imperial army of some 50,000 approached, Žižka

deployed his wagon fort in front of the city walls, stretched over a sufficient

length to cover both western roads into the city. Scolari, in military command

of this operation, stretched his cavalry in a thin line to face the wagons and

attacked repeatedly throughout the day. The Hussite cannon inflicted heavy

casualties, but this action also kept the Hussite attention focused to the

west. Scolari and Sigismund appreciated the leanings of the Germanic citizens

of Kutná Hora and had secretly contacted their leaders. With the battle raging

outside the walls, an imperial cavalry force had swung wide south and

approached the gate on the Malesov road, which conspirators opened to them. The

small garrison Žižka had left in the city was quickly overwhelmed and the

Hussites were now surrounded.

Žižka found himself in the most dangerous position of his

career, but his brilliant mind was not daunted. Sigismund had delayed entering

the city until he could do so in triumph; he was still in his headquarters on

the imperial left flank. Žižka decided to launch an ambitious surprise attack,

assailing the enemy leader’s headquarters at sunrise. Knowing the enemy once

again provide invaluable, as Žižka knew that Sigismund never put himself in

danger; he always commanded from the rear. Thus, the Hussites were sure he

would not lead any resistance that was aimed directly at him, being too

interested in getting himself out of the way. Just before dawn on 22 December,

Žižka formed his wagons into line and opened fire on Sigismund’s headquarters.

No one expected this gunfire to come out of the night and, as Žižka had

planned, panic ensued in the imperial ranks. Although the column stopped now

and then to reload and shoot again, preventing a constant moving line of

artillery fire, it was nevertheless enough to scatter the defenders and leave a

hole in their lines through which the Hussites made their escape. Žižka’s

decision to attack at night had been a good one; a daylight gambit along these

lines probably would not have been successful.

As dawn broke the Hussite wagons were out of sight, and

Žižka deployed them on a hill about a mile away and prepared for the pursuit,

which never came. Once positive he would not be caught in the open, Žižka moved

his men to Kolín, from whence he spent the next two weeks scouring the region

for reinforcements. In the meantime, Sigismund (assuming his enemy was on the

run and would not be a bother until spring, if at all) had settled himself into

Kutná Hora. He could not quarter all his men in the town, so he dispersed them

to villages around the region, paying particular attention to Cáslav, a Hussite

stronghold just to the east, and to Nebovidy, about halfway to Kolín, to act as

a covering force. Žižka took advantage of this dispersal on 6 January when he

surprised the force at Nebovidy. Unfortunately, no sources give details of the

next few battles, other than to say the Hussites attacked and the imperial

troops broke. An anonymous late nineteenth-century description, probably taken

from the George Sand biography of Žižka, says that Žižka “suddenly burst upon

Sigismund’s scattered troops like a thunderbolt. Hundreds of Hungarians were

cut down at the first onslaught, and the panic spread with awful rapidity from

village to village.” No one else provides any more detail.

What is important is that the crusaders fled toward Kutná

Hora and created a panic there, especially in Sigismund’s heart and mind. He

fruitlessly begged the German town elders to defend the city from Žižka’s army

while he withdrew, then ordered the city burned rather than let it fall into

Hussite hands. The citizens were hustled unprepared out of the town while a

Hungarian cavalry contingent remained behind to light the fires. Their desire

for loot, coupled with the speed of Žižka’s pursuit, however, meant that few

fires were actually set, and those were quickly extinguished. The pursuit

continued, as did the panic. Sigismund decided to make a stand a few miles to

the southwest at Habry. His advisors, particular Scolari, counseled against it:

the troops were too demoralized. The advisors were right, though Sigismund

didn’t listen. When the Hussites did attack, the defenders once again turned

tail. The rout was total, with the crusaders abandoning everything but personal

arms in their haste. Again, no details of assault or defense are available.

Sigismund fled for the Moravian border town of Jihlava. He

crossed the Sázava River at Německý Brod, well ahead of his army, some of whom

again tried to make a stand, but the hot Hussite pursuit forced a mad dash

across the frozen river. It was not, however, totally frozen, and the breaking

ice led to the drowning of a reported 548 knights. A hasty defense of the town

was soon rendered useless by Hussite heavy artillery that made short work of

the walls. An attempted negotiated surrender fell apart when a Hussite patrol

found a particularly weak section of wall and broke through without orders, setting

the fighting off once again.

In the wake of the Hussite victory and the ensuing pillage,

and a similar lapse of control a year later, Žižka developed one of history’s

first sets of regulations of war, dictating the behavior of troops in and out

of combat. Overall, the combat between 6–9 January 1422 cost the imperial

forces at least 4,500 dead; there is no account of Hussite casualties, but they

must have been very light.

The campaign beginning at Kutná Hora and ending at Německý

Brod showed Žižka at his best on offense and defense. He had several days to

prepare his wagenburg outside Kutná Hora, and it dealt heavy casualties to the

imperial cavalry that attacked it. When he found himself betrayed by the

townspeople and cut off, Žižka massed his combat power at a single weak point,

the king’s headquarters, and through firepower and psychological intimidation

paralyzed his opponent and made good his own escape. Taking advantage of his

opponent’s assumption of victory, his innate proclivity not to fight, and the

dispersed nature of his army, the offensive that began on 6 January combined

all the elements of the offense: surprise, concentration, control of tempo, and

audacity. His movement to contact led to a deliberate attack, followed by

immediate exploitation and long-range pursuit. One has to be amazed at the

ability of a blind general to command a breakout from encirclement, then follow

it up with a cross-country pursuit of a broken enemy, and all in the dead of

winter. This was not typical medieval warfare.

In the grand strategic scheme of things, the campaign had

major significance as well. It ended the second crusade and so disheartened

Sigismund that he did not approach Bohemia himself for years. By keeping

himself in Hungary and letting the German princes conduct the future crusades,

he alleviated Bohemia’s necessity to prepare for or fight a two-front war.

Žižka’s reputation, as well as that of his followers, remained one of the most

important factors in the three crusades that followed over the next few years.

One of the crusading armies barely got inside Bohemia when the sounds of

Hussite soldiers singing one of Žižka’s war songs frightened the invaders out

of the country without a battle. Hans Delbruck notes, “Once the warlike

character had gained the upper hand and had become completely dominant, the

Hussites were preceded by a wave of fear so that the Germans dispersed before

them whenever they simply heard their battle song from afar.”

Unfortunately for the Hussite cause, internal feuds caused

more troubles than did invasions. Although the wagenburg tactic became standard

for all Hussite forces, they used it against each other at times, as in the

last of Žižka’s great victories at Malesov against a rival religious faction.

Žižka would ultimately die of the plague while preparing an invasion of Moravia

in 1424, and his leadership position was ably taken up by Prokop the Great, who

continued the long line of Hussite victories over German Catholic crusades.

Finally, in 1434, a truce was signed that granted the Hussites some

concessions. They remained outside the good graces of the church, which,

however, did not reestablish its authority in Bohemia until two centuries later

at the Battle of White Mountain at the start of the Thirty Years War.

Žižka’s Generalship

Jan Žižka was certainly the most imaginative general of the

late medieval–early Renaissance period. Although he was not the first to use

gunpowder weapons, he was more forward-thinking than anyone of his time in how

to employ them. His use of soldiers from the lower economic classes was also

employed by England with the longbowmen of the Hundred Years War and by the

Swiss pikemen, and as Charles Oman observes, contributed to “the overthrow of

feudal cavalry—and to no small extent [to] that of feudalism itself.” The

strengths of Žižka’s leadership were his mastery of maneuver, surprise,

simplicity, and morale.

The goal of maneuver is to place the enemy in a

disadvantageous position. For Žižka, this meant obliging his heavy cavalry

enemy to attack a position across terrain for which it was not suited. The

first two battles covered, Sudoměř and Vitkov Hill, show this perfectly. The

Bohemians were on narrow raised ground with steeply falling sides, forcing the

attackers into a narrow front where their strength of numbers was negated. The

Bohemians drew their enemy into an attack against a fortified position in order

to employ superior firepower. The ability to force a disadvantageous position

depended on knowing the nature of the enemy’s mind-set as much as their

tactics. Žižka knew the knights would not take a peasant force seriously, no

matter what their position. Hence, he drew the imperial cavalry into attack

after attack against fortified positions that horses could not penetrate and

where infantry or dismounted knights had to fight hand-to-hand against soldiers

with a height advantage in the wagons. The peasant defenders, using spears and

flails, also had superior reach against foot soldiers armed with swords.

Žižka also employed maneuver in the offensive-defensive

nature of his warfare. Although he did engage in siege work, that was a

traditional practice of warfare albeit with the newly implemented heavy cannon.

His wagenburg, however, could be used across most of the relatively level

Bohemian terrain. Thus, he could take war to the enemy, but employ the strength

of a defensive position against armies that did not employ the necessary

weaponry. As long as Žižka carried the firearms and his enemy did not, all he

had to do was make sure his wagenburg was deployed before the enemy struck.

This, of course, is what made the wagenburg a relatively short-lived aspect of

warfare, for armies would soon be employing their own firearms, and the wooden

wagons could only absorb so much gunfire, unlike the archery fire they had

dealt with in the early fifteenth century.

The first time any new tactic or weapon is introduced it

produces surprise, and Žižka’s wagon-borne firearms were no exception. This is

what makes Žižka, like the other generals studied in this work, stand out: he

saw the strengths and weaknesses of his own forces and the enemy’s, and he

adapted his strength to their weakness. His first two surprises therefore went

hand in hand: the wagenburg and the peasant soldier. The shock of facing

gunpowder arms in large numbers had to have amazed the knights at Sudoměř, no

matter what actual damage was inflicted. This was the first time that guns had

been used in massed defensive positions, and the effects were notable. The

noise was terrifying in itself, and it combined with the gunpowder flashes and

thick smoke to confuse enemy troops. The horses apparently began to get over it

after a time, for by the battle at Kutná Hora the imperial cavalry attacked

repeatedly throughout the day. Even if the actual damage inflicted by the

handguns and small cannon was not great, it was supplemented by arrows and

crossbow bolts.

The nature of the wagenburg would have been surprising

enough when first encountered, but his quick shift from defense to breakout at

Kutná Hora, as well as the fact that he attacked at night, again show Žižka’s

ability to think outside the box. He knew his enemy’s general attitude toward

the nature of combat and the personal attitude of Sigismund, and he played on

them both to paralyze his enemy—even if he inflicted few casualties. In the

battles that followed, his quick strikes and close pursuit were like nothing

his enemies had encountered. This again was not normal medieval warfare, for

the usual aftermath of battle was a peaceful withdrawal. The Hussites, however,

did not act in accepted knightly fashion and the crusader knights don’t seem to

have adapted. Heymann notes that while it was fairly common for medieval

generals to pursue an enemy, “to follow up a victory by a continued pursuit

over scores of miles, to press on after a beaten enemy so as to achieve his

complete destruction—this was by no means usual or ‘normal.’ It was ‘normal’

only for Žižka who always acted according to the military needs of the

situation as his unfettered mind saw them.”

Žižka’s soldiers were a surprise to their enemies not

necessarily because they were peasants, but because they were disciplined.

Showalter observes, “Medieval armies lacked anything like a comprehensive

command structure able to evoke general, conditioned responses…. At their best

the civil militias of urban Europe were part-time fighting men. Their tactical

skills were correspondingly limited.” Žižka benefited from his own military

experience as a guerrilla fighter and also had the all-important motivating

factor of religion to help keep his troops disciplined. Žižka did not really

ask his soldiers to do anything out of the ordinary as far as their abilities

were concerned, as driving wagons and handling tools were second nature. In

this way Žižka brilliantly implemented the principle of simplicity. The

gunpowder weapons were so basic that no real training was necessary to handle

them. He also taught his army of farmers to fight as well as they could with

the tools they knew best: scythes, iron-tipped grain flails, axes, rakes,

picks, hoes—implements that turned out to be vicious at close quarters when

wielded by people who were very strong, very motivated, and used to hard labor.

Žižka’s experience, coupled with a zeal that matched or

exceeded their own, made him a leader his men could follow into any situation,

and they could easily accomplish the assigned tasks within the wagons on the

move or when deployed into the fortress. The Hussites’ early victories sufficed

to give them the confidence they needed to buy into the fixed way of doing

things, and their do-or-die attitude of fighting for God against heretics and

aristocrats tapped into their already existing attitudes and emotions. None of

the disciplined movements or fanatical willingness to fight were things for

which the invading crusaders were prepared. The most complex maneuver Žižka

ever asked of his men was forming up in a straight line and following each

other into Sigismund’s headquarters, stopping periodically to shoot into the

dark to keep the enemy disorganized. Other than that (and the necessary

movements to create the wagenburg), all their actions were straightforward

attack or defense. Only the two-pronged attack out of Prague up the Vitkov Hill

showed anything like sophistication.

Žižka was also a skilled commander when it came to the

principle of morale. Religion is an incredibly motivating cause, and Žižka used

this to his advantage to keep the morale of his troops high. He showed himself

to be more religious than the conservatives controlling Prague, but not as

radical as the millenarian sects that emerged in the wake of Jan Hus’s death.

His belief was never in doubt, even when he made war against the radical

factions, made up of the lowest rung of society. He maintained the loyalty of

the rank-and-file Hussites and the respect of the conservatives, who looked for

some sort of compromise with the church. But it was for social and economic

advancement and freedom from outside rule, as well as religious freedom, that

his people followed him. Žižka could therefore rely on the support of the

country people and urban poor who brought their own weapons with them.

While religion may have been the glue holding the army

together, it was discipline that gave it shape. A disciplined force always has

greater unit cohesion and therefore fights better than one lacking in those

traits. Žižka set rigid standards: each man was assigned a place in ranks with

a specific tactical mission. Straggling, disobedience, and disorderly conduct

were severely punished. Promotion was based on ability rather than social

status and the serf was considered the equal of the noble. We have seen this

same attitude in most of the generals discussed thus far: ability trumps birth.

That was just as true concerning punishment, and equal justice maintained

belief in the system.

And then, of course, there was the man himself. When he

still had his sight, he fought alongside his troops. Sharing dangers and

conditions always promotes loyalty to a leader. Then, when he completely lost

his sight, he still commanded in the field for another three years. For a

religious peasant army, that was surely a sign of God’s grace. It also

illustrates how Žižka’s reputation became a demoralizing factor for his

enemies. Žižka’s regular victories gave him an air of invincibility on both

sides of the battlefield, and the songs he wrote for his troops (a mixture of

hymn and military instruction) were as frightening to his enemies as the

Hussites’ crude weapons.

Jan Žižka is unfortunately not a widely known figure outside

central Europe, but no work on him or on the Hussites fails to describe him as

a genius, the most talented general of his time. Although his wagenburg was

effective for only a short period in military history, it shows what one

imaginative leader can do with the materials at hand to exploit an innate but

often unseen weakness in his enemy. Unseen, that is, except to a blind old man.