In 530 BCE Cambyses inherited a vast empire, far larger than

any previous, and one that had been formulated in just twenty years. Cambyses’

royal pursuits are hard to gauge, however, because the record is even thinner

for his reign. Cambyses’ first order of business would have been arrangements

for Cyrus’ burial at his tomb in Pasargadae. An incomplete structure found near

Persepolis has been identified as an intentional replica of Cyrus’ tomb, and it

was naturally assumed to have been for Cambyses. But some documentary evidence

suggests that Cambyses’ tomb lay elsewhere, southeast of Persepolis near modern

Niriz, and the evidence pointing there indicates a royally sponsored cult,

similar to that associated with Cyrus’ tomb.

Cambyses eventually turned his attention westward, where the

main power was Egypt. Amasis (reigned 570–526 BCE) had conquered Cyprus and

formed an alliance with the Greek ruler Polycrates of Samos, an island off the

coast of Ionia. By the 520s Polycrates had become dominant in the Aegean Sea

region. This alliance was fractured sometime after Cambyses’ accession, and

Polycrates offered ships to Cambyses for the Egyptian expedition. Reasons for

the switch may only be guessed. Perhaps the intensifying Persian hold on Ionia

in conjunction with inducements (or threats?) swayed Polycrates toward Persia.

Cambyses’ efforts to develop a royal navy, mainly through his Phoenician and

Ionian subjects, were no doubt intended for the western front and a planned

Egyptian campaign. The territories of the Levant, geographically at the

crossroads between Greater Mesopotamia and Egypt, had been a point of contention

between rulers of those regions for centuries. Persian control of that region

was bound to inflame tensions with Egypt. With an eye on Persian expansionism,

Amasis had cultivated good relations with many city-states and sanctuaries in

the Aegean world. In 526 Amasis was succeeded by his son Psammetichus III,

whose rule was to prove quite short.

Cambyses’ Invasion of

Egypt

There is no narrative record of the preparations for the

Persian invasion of Egypt in 525 BCE, but they were no doubt extensive. As part

of these preparations, Cambyses fostered relations with the king of the Arabs,

who controlled the desert route across the Sinai peninsula and could thus

enable the successful crossing. The first engagement occurred at the

easternmost branch of the Nile delta, the so-called Pelusiac mouth. The

Persians put the Egyptians to flight, invaded the Nile Valley, and besieged

Psammetichus in his capital, Memphis. There he was protected by fortifications

named “the White Wall,” which could only be taken with support from a fleet.

The city was eventually taken and Psammetichus captured. But he was spared and

treated well, as per the pattern of kings previously defeated by the Persians.

Herodotus even claims that if Psammetichus had comported himself appropriately

he would have been made governor of Egypt (3.15). But Psammetichus subsequently

plotted rebellion and was put to death.

Once Egypt was secure, Cambyses intended further military

actions both west and south, following the paths of many Egyptian pharaohs. The

Libyan oases offered control over strategic western trade routes. Beyond the

First Cataract in the south, the kingdom of Kush had always been coveted for

its gold. The installation of a Persian garrison at Elephantine – an island in

the Nile near modern Aswan – reveals the strategic importance of this area at

Egypt’s southern boundary. This garrison was one of several similar that were

stationed at strategic points throughout the Empire.

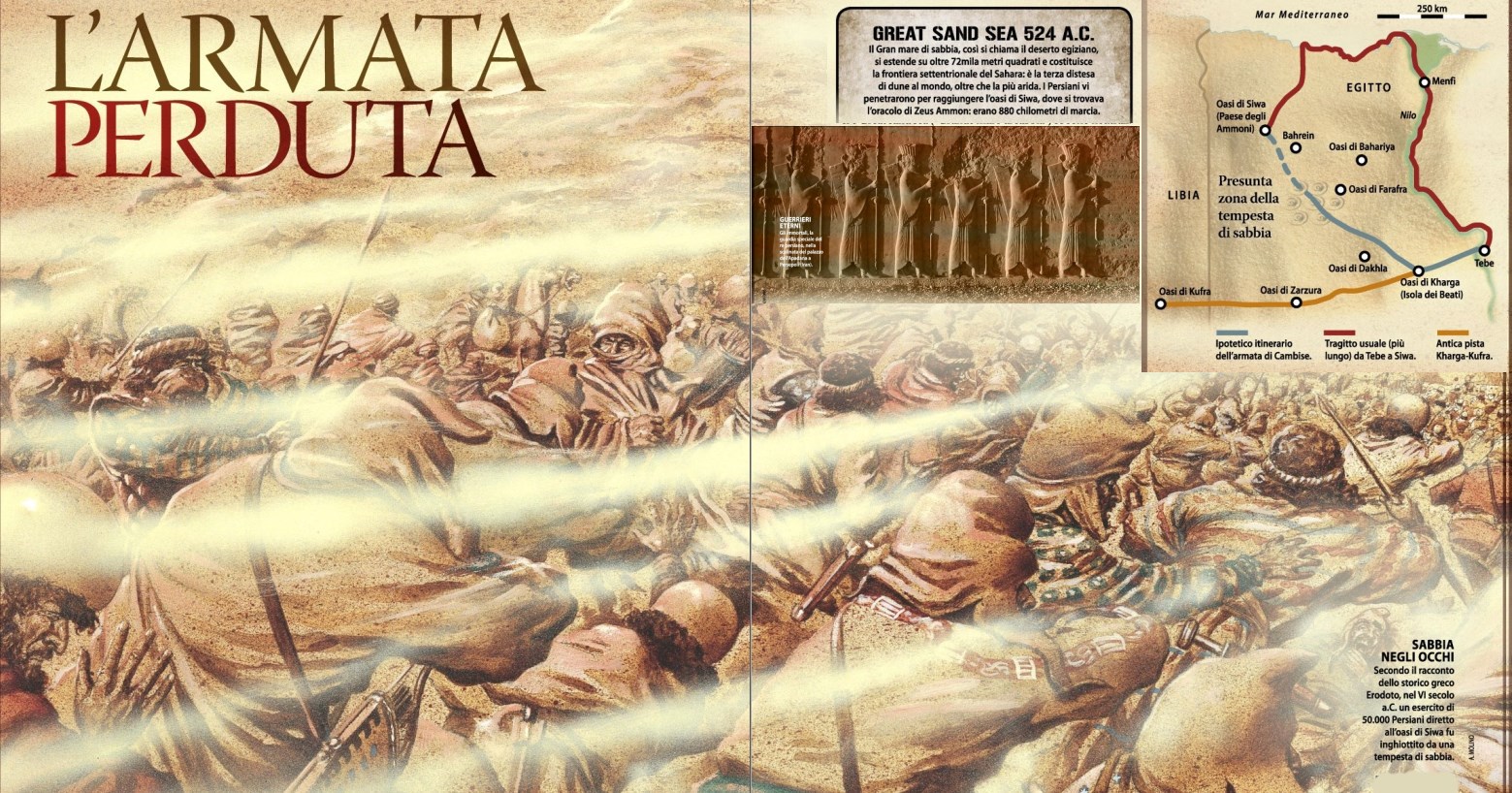

Additional Persian expeditions against the oasis of Ammon in

the west and against Nubia and Ethiopia in the south ended badly. The

particulars may seem far-fetched, but the historicity of these campaigns,

including an aborted expedition against the Carthaginians (modern Tunisia),

need not be rejected out of hand. The limits of Persian imperialism had not yet

been reached. It made sense to secure those borderlands that had been problems

for previous Egyptian rulers for centuries. If Herodotus may be believed, the

army dispatched to Libya was swallowed in a sandstorm. Cambyses himself led the

expedition against Nubia and Ethiopia, but it was abandoned en route: desperate

straits culminated in cannibalism among the troops. These misadventures,

replete with divine portents and human warnings that Cambyses was going too

far, serve as case studies for Herodotus’ portrayal of the “mad Cambyses” –

more a literary exercise than a historical one. Herodotus records a litany of Cambyses’

outrages, overreach, and arrogance – directed not only at Egyptians but also at

Persians and even his own family – the paradigmatic example of a stereotypical

oriental despot.

Herodotus’ “mad Cambyses” shows first of all that the Father

of History relied on a negative tradition of Cambyses current in Egypt when

Herodotus visited in the mid-fifth century BCE. Herodotus devotes portions of

his Book 3 to Cambyses’ increasing instability. Cambyses purportedly ordered

Amasis’ mummy to be disinterred, abused, and finally burned – an insult, to

both Persian and Egyptian religions (3.16). Other tombs were opened and cult

statues mocked, particularly in the temple of Ptah, an Egyptian creator god

whose sacred city was Memphis. The greatest outrage to the Egyptians was the

slaying of the Apis bull (3.27–29), a sacred calf that was considered the

earthly embodiment of Ptah. The Egyptian king was a central part of the Apis

cult, which in turn was directly connected to the office of kingship.

When Cambyses returned to Memphis after the disastrous

Ethiopian expedition, he found the Egyptians of Memphis celebrating the birth

of a new Apis calf: a new beginning, their god again made manifest. Cambyses

snapped. He saw their festival as an expression of joy at his misfortune, and

he reacted: stabbing the Apis bull with a knife to the thigh and flogging or

slaying many priests. Herodotus subsequently catalogs a cascade of misfortune

and misery that brought Cambyses to his own end and shook the entire Empire to

its core – the result of Cambyses’ impiety. The slaying of the Apis bull makes

compelling drama, but it is mostly exaggerated if not fabricated. We have some

Egyptian evidence that seems to refute Herodotus’ portrayal. Contrary to

Herodotus’ assertion that the Egyptian priests buried the Apis bull without

Cambyses’ knowledge, a sarcophagus from a bull buried during Cambyses’ reign is

engraved with Cambyses’ own inscription in traditional Egyptian format:

The Horus Sma-Towy,

King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Mesuti-Re, born of Re, Cambyses, may he live

forever! He has made this fine monument, a great sarcophagus of granite, for

his father Apis-Osiris, dedicated by the King of Upper and Lower Egypt,

Mesuti-Re, son of Re, Cambyses, may he be granted long life, prosperity in

perpetuity, health and joy, appearing as King of Upper and Lower Egypt

eternally.

This inscription states that Cambyses, acting as a typical

Egyptian pharaoh, took responsibility for the proper care and burial of the

deceased Apis, which is understood to have died during Cambyses’ fifth regnal

year. If only it were so simple. There are significant problems with our

understanding of this sequence: the death and burial of the Apis bull during

Cambyses’ reign, and the overlap between the birth of a successor bull and the

death of the current Apis. Other inscriptions further complicate matters.

Although the initial inclination is to reject any suggestion

that Cambyses killed the Apis, it cannot be excluded that Cambyses may have

killed a younger calf (the Apis successor) before the death of the one buried

in the sarcophagus. The Egyptian evidence reminds us not to take Herodotus at

face value. Some of the changes Cambyses wrought in the aftermath of the

Persian victory must have been unwelcome, perhaps even unprecedented. For

example, a reduction in support for some Egyptian temples could easily have

given rise to negative stories about Cambyses.

The inscription of Udjahorresnet, a naval commander under

Amasis and Psammetichus III who defected to the Persians, also provides some

balance to Herodotus’ account. Udjahorresnet’s hieroglyphic inscription is

carved on his votive statue from Sais, in the western Delta. The statue holds a

small shrine for Osiris, god of the underworld. The autobiographical

inscription chronicles Udjahorresnet’s career, with special emphasis on his

service to both Cambyses and Darius I. It is invaluable as a window on how one

of the Egyptian nobility secured a place for himself in the new order.

Udjahorresnet’s inscription provides the only surviving

royal titles for Cambyses beyond Babylonian administrative documents. Cambyses

adopted Egyptian titles (e.g., “King of Upper and Lower Egypt”) as would be

expected from a new ruler seeking to place himself in an age-old tradition.

Udjahorresnet himself would have been keen to trumpet his own titles and

achievements – typical in this sort of inscription – and also to justify his

collaboration with the Persians. Udjahorresnet’s inscription, and Cambyses’

titles therein, indicate that Cambyses behaved as did previous kings by

restoring order and respecting religious sanctuaries. Udjahorresnet’s version

is no doubt slanted as well, but the picture it provides runs directly counter

to Herodotus’. It would not be surprising to discover that the respect Cambyses

showed for sanctuaries included those with which Udjahorresnet had been

involved, those in and near Sais, but that is unverifiable. That the Persians

presented themselves as pharaohs in the traditional Egpytian manner is not

surprising. Successful integration into Egyptian tradition would make Persian

rule much smoother. As evidenced by subsequent Egyptian revolts, however, this

integration was not always smooth.

The Death of Cambyses

and the Crisis of 522 BCE

The length of Cambyses’ Egyptian campaign is uncertain, but

various sources indicate that Cambyses was returning to Persia in 522 when he

died. He had been away for at least three years. Babylonian economic documents

reveal that Cambyses died sometime in April and was succeeded by his brother

Bardiya. Bardiya ruled for six months, until he was supplanted by Darius.

Darius conversely related that Cambyses had killed Bardiya sometime previously

and that a look-alike double, whom Darius called Gaumata, rebelled against

Cambyses in March of 522. The crisis of 522 was of epic proportions, and the

stability of the fledgling Empire was at stake. Various ancient sources relay a

story of fratricide; an elaborate cover-up; a body double and impostor on the

throne; and a small group of heroes who discover the truth, slay the pretender,

and set Persia to rights once again. Despite the fundamental interpretive problems

that persist in evaluating the sources, it is clear that the Persian Empire

faced a decisive moment. Darius I’s eventual, and by no means easy, victory was

monumental in its own right and had lasting consequences for the durability of

the Empire. The testimonies for this turbulent time are confusing and often

contradictory. Separate overviews of the main ones – Darius’ Bisitun

Inscription and Herodotus’ account – are warranted before any attempt at

reconciliation.