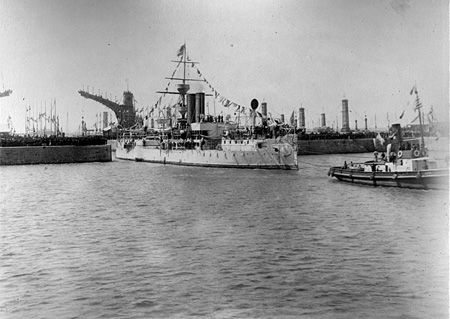

Riachuelo (1883) – Presidential visit to Buenos Aires in 1900

The Empire of Brazil, c. 1889. Cisplatina had been lost since 1828 and two new provinces had been created since then (Amazonas and Paraná)

The Paraguayan War

and the ‘Military Question’

Brazilian participation in the Paraguayan War of 1864–70 had

dire consequences for the country. It is a war that has become notorious for

causing more deaths in proportion to the number of people who fought in it than

any other war in history. It also created a new generation of junior officers

who differed from those who had gone before. They were educated men – very

often having attended universities abroad – who had less regard for the

monarchy than their predecessors.

Uruguay had come into existence in 1828 after three years of

conflict between Argentina, Brazil and the faction seeking independence for the

region. The British, with financial and commercial interests in the River Plate

estuary, were very pleased to see the creation of a country that they hoped

would bring stability to the region. The nineteenth century brought unrest,

however, as Uruguay’s two political parties – the Colorado, linked to business interests

and Europe, and the Blanco, made up of rural landowners who opposed European

influence – vied for power, often violently. Meanwhile, the inhabitants of the

old Spanish province of Paraguay had overthrown their Spanish administration in

1811. In 1842, President Carlos Antonio López (1792–1862) declared himself

dictator and in 1862 his son, Francisco Solano López (1827–70), came to power

following his father’s death. That year he entered into an alliance with the

Blanco Party that ruled Uruguay at the time. Fighting broke out between the

Blancos and Colorados and spilled over into Rio Grande do Sul in southern

Brazil, spurring the Brazilians to invade Uruguay in order to help the

Colorados seize power. The Uruguayans captured a Brazilian ship and then invaded

the Mato Grosso region in western Brazil. In 1865, the Paraguayans planned to

invade Uruguay but this would involve them in crossing Argentinean territory.

Subsequently, on 1 May, Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay entered into a Triple

Alliance and declared war on Paraguay. The Paraguayans did not attack Uruguay

as planned and all the fighting actually took place in Paraguay itself.

Brazil was not prepared for war although its navy,

consisting of a few warships, easily defeated the tiny Paraguayan navy. Its

army, consisting of only 18,000 poorly trained fighting men, had long been

neglected. The desperate Brazilian government promised slaves their freedom if

they enlisted. Finally, in 1866, the Brazilian army invaded Paraguay but was

defeated in its first engagement at the Battle of Curupayty. In summer 1867,

however, the Duke of Caxias led the siege and capture of the important fortress

at Humaitá in southern Paraguay. The capital was taken a short while later.

Brazil would occupy Paraguay until 1878.

The war was costly for Brazil. It brought a steep rise in

inflation and the empire’s foreign debt increased. The most telling consequence

was the effect on the army. Its prestige and influence, as well as its size,

were greatly increased by the conflict. The officers, whose number increased

from 1,500 to 10,000, were now politicised but were uncomfortable with what

appeared to be an anti-military stance emanating from the emperor. Indeed, he

had deliberately eschewed the caudilho, military style of leadership that was

popular amongst many Spanish-American rulers and was careful not to appoint

military men to high-ranking political positions. The officer corps’ disquiet

was increased by the enforced resignation of the Liberal Prime Minister,

Zacarias de Góis e Vasconcelos (1815–77), whose direction of the war effort had

been to their liking. Only the fact that the military commander Caxias remained

loyal to Pedro eased their feelings of discontent. His death in 1880,

therefore, was a blow not only to the emperor personally, but had grave

implications for the future of the monarchy.

The junior officers’ irritation at the failure of the

government to improve army pay and conditions developed into a feeling of

political disenchantment and the beginnings of a movement to reform Brazil’s

political system. Officers were barred from political activity but in 1879 a

group of officers publicly criticised a proposal before the General Assembly to

cut the size of the army. No action was taken against them but in the coming years

when officers again engaged in political debate, they would be disciplined.

The ‘military question’, as it was known, became a source of

growing tension between the army and the government. The unrest soon spread to

senior officers who demonstrated support for their younger colleagues. The main

spokesman was Marshal Manuel Deodoro da Fonseca (1827–92) who, in 1887, was

elected first president of Brazil’s Club Militar (Military Club), a society

created to uphold soldiers’ rights. Tension rose when, in June 1889, Emperor

Pedro appointed a Liberal, the Viscount of Ouro Preto (1836–1912), as prime

minister. Ouro Preto wasted no time in antagonising Deodoro by naming an

opponent of his as president of Rio Grande do Sul.

The Military Coup of

1889

For some time, Republican politicians had been cultivating

friendships with the military, realising that as neither elections nor the

General Assembly were likely to bring the empire to an end it would take the

support of the army to do so. In 1887, Marshal Deodoro wrote to the emperor,

warning him about his attitude towards the Brazilian military and indicating to

him that the ongoing support of the army could not be guaranteed. Meanwhile,

his fellow officers were eager to replace the empire with a republic, amongst them

men such as Benjamin Constant (1836–1891), like Deodoro a veteran of the

Paraguayan War. Meanwhile, Pedro II was suffering from diabetes and, although

only 64, was becoming increasingly frail. He seemed to have lost interest in

the business of government and it has been suggested that he had already

accepted that the empire would not survive his death. The fact that he had no

male heir suggested that he had good reason to fear for the empire’s survival.

His daughter, Princess Isabel (1846–1921), who had already courted controversy

with her support for abolitionism, was the legal heir, but it was highly

unlikely that a male-dominated society like Brazil would be prepared to accept

a woman on the throne. As if it was not bad enough that she was a woman, her

husband, Prince Gaston, Count of Eu (1842–1922), was French.

There was a growing feeling in Brazil that too much power

was vested in the emperor, the Senate and the Council of State, none of whom,

after all, had been elected. As republican clamour grew, Ouro Preto introduced

measures to reduce the power of the Council of State, the General Assembly and

the provincial presidents, but they were thrown out by the General Assembly.

The emperor responded to this setback in the customary manner, by dissolving the

General Assembly and calling for new elections to be held in November 1889. It

was obvious that nothing was likely to change. The military responded by

ordering Benjamin Constant, in concert with Republicans such as Quintino

Bocaiúva (1836–1912) and Rui Barbosa (1849–1923), to devise plans for a coup.

Early in the morning of 15 November 1889, troops commanded by Deodoro, who had

agreed to be the coup’s leader, surrounded government buildings in Rio de

Janeiro. It was initially supposed that the action was intended simply to

change the cabinet, but that afternoon Deodoro declared that Pedro II had been

overthrown and that Brazil would henceforth be a republic.

That day, Pedro was at his summer palace at Petrópolis,

outside Rio de Janeiro. After hurrying back to the capital, he was ordered to

leave Brazil within twenty-four hours, taking the rest of the royal family with

him. On 17 November, he sailed into exile in Portugal and France, choosing this

fate rather than subject Brazil to an inevitable civil war. All proceeded

peacefully, although many observers were astonished at the lack of support for

the monarchy. Robert Adams Jr (1849–1906), United States Minister to Brazil at

the time of the coup, wrote that it was ‘the most remarkable ever recorded in

history. Entirely unexpected by the Government or people, the overthrow of the

Empire has been accomplished without bloodshed, without riotous proceedings or

interruptions to the usual avocations of life’.

Estados Unidos do

Brazil (United States of Brazil)

The leaders of the coup of 1889 immediately established

their regime as a ‘provisional’ government, declaring Brazil a federal

republic. They issued proclamations justifying their action, claiming that they

had undertaken the coup on behalf of the Brazilian people. Deodoro was in

charge as ‘chief of the provisional government’ and a number of prominent

politicians quickly rallied to his cause, including Rui Barbosa, Quintino

Bocaiúva and Benjamin Constant, who were each rewarded with a position in the

new government. Rui accepted the position of Finance Minister, Constant was

appointed Minister for War and Quintino took office as Minister of Foreign

Relations. The formal name of the country was changed from the Empire of Brazil

to the Republic of the United States of Brazil and a new national flag was

designed. Work began on a new constitution, the aim being to transform Brazil

into a modern, industrial democracy.

The new constitution advocated a federal political system,

fulfilling the objectives of a Republican manifesto of 1870 that had demanded

the transfer of power from the centre to the regions, a move welcomed by the

influential coffee industry, especially in São Paulo. As in the days of the

Empire, however, there would still be a central executive administration, with

a national legislature based in Rio de Janeiro. The Liberals considered this to

be the best way of maintaining national unity and merchants and businessmen

hoped it would help create a domestic market. It was decided to follow the

political model of the United States, with a president and a federal government

made up of executive, legislative and judicial bodies. The president would be

elected by the people for a four-year term and would be prohibited from serving

consecutive terms. The franchise was limited to literate males over the age of

twenty-one, representing about 17 per cent of the population. A large majority

of the Brazilian people were still unable to participate in the choice of their

ruler. The rest of the world was expanding the franchise, but Brazil, still

afraid of the will of the people, was reluctant to follow the trend.

Legislative power was placed in the hands of a National

Congress which, like its imperial predecessor, the General Assembly, would

consist of a Chamber of Deputies and a Senate. Each state was allocated three

senators, each of whom would serve nine years before standing for re-election.

The deputies would serve terms of three years and would be elected on the basis

of population, the more highly populated states benefiting most from this, of

course. Inevitably, elections were rigged. Voters in rural areas were forced to

vote for the chosen candidates of the local oligarch – an abuse known as

coronelismo. If all else failed, the election results could still be changed by

Congress’s Verification of Powers Commission as the election authorities in the

República Velha (Old Republic), were not independent from the executive and the

legislature and those were, of course, controlled by the ruling elite.

The twenty provinces that had existed under the empire

became twenty-one with the creation of the new Federal District of the city of

Rio de Janeiro. Each was permitted to create its own constitution and be

self-governing, with directly elected governors and their own legislative

assemblies and courts. They were given financial autonomy with the power to

levy taxes on exports, this being particularly welcomed by São Paulo and Minas

Gerais, two states with lucrative export economies. States were permitted to

establish their own militias or police forces and São Paulo even had its own

army which was every bit as well-equipped as the national army.

Church and state were separated, meaning that Brazil no

longer had a state religion. The state assumed many of the responsibilities formerly

held by the church – only civil marriages would be officially recognised and

cemeteries were taken over by municipalities. These measures were a reflection

of the beliefs of the republican leaders but also brought the many Lutheran

immigrants in Brazil into the national fold. To further embrace its immigrant

population, the government passed a measure decreeing that unless they

expressed a wish otherwise, all foreigners who had been in Brazil on 15

November when the Brazilian Republic came into being would automatically be

considered Brazilian citizens.

Generally speaking, the power lay not only with the newly

politicised professional military class but also in the hands of the planter

elite based mainly in the coffee-producing regions of São Paulo and the

commercial and banking interests concentrated in the cities of Rio de Janeiro,

São Paulo and Minas Gerais. For most people little changed but army officers

probably benefited more than most with increased salaries and lucrative

appointments to government positions. The elite, along with the military,

therefore, still controlled the machinery of government and, although a few

liberals, such as Rui Barbosa, tried to persuade the government to introduce

reforms in education and working conditions and pay and to consider the issue

of land reform, nothing would really change until well into the next century.

In effect, of course, what had occurred was a military coup.

The army ruled as a military dictatorship for the first five years following

the coup in what was known as the ‘Republic of the Sword’. Inevitably there

were clashes between politicians and the newly politicised army officers,

especially Deodoro who was authoritarian by nature. Eventually, in January

1891, the cabinet resigned. Meanwhile, the constitution demanded the election

of the first president of the Republic who would serve until 1894. Deodoro was

the obvious choice, but opponents to the military’s involvement in government

put forward a rival candidate, Prudente de Morais (1841–1902), president of the

Constituent Assembly and a former governor of São Paulo. As anticipated,

Deodoro won, by 129 votes to 97, and was sworn in as the first President of the

Republic of Brazil on 26 February 1891. The margin of victory was sufficiently

small to suggest that the new president was not the most popular of choices,

but, as everyone was well aware, if he had lost, the army would almost

certainly have stepped in and declared a dictatorship.

Deodoro took office amidst unrest, much of it caused by the

economic crisis, the Encilhamento, a word borrowed from horse racing and

suggestive of efforts to get rich quick. His handling of this situation was

calamitous and gained him the animosity of Congress as did his lack of control

over his ministries. Congress obstructed him at every opportunity. The

Republicans from the South eventually withdrew their support from him and the

provisional government. When the government was accused of corruption in

November 1891, Deodoro dissolved the new National Congress, declaring a ‘state

of emergency’ and assuming virtual dictatorial power, something for which he

was heavily criticised and which lost him a great deal of support, even within

the army. The vice president, Marshal Floriano Peixoto (1839–1895), conspired

with other officers, leading to the seizure of warships in Guanabara Bay by

Admiral Custódio José de Melo (1840–1902). De Melo threatened to open fire on

Rio de Janeiro unless Deodoro recalled Congress. Deodoro responded by resigning

on 23 November 1891 and Floriano, as Peixoto was popularly known, assumed the

presidency, immediately recalling Congress.

The republic’s second president – known as the ‘Iron

Marshal’ – gained a reputation as an upholder of the constitution, but although

he is said to have had a better understanding of ordinary people than his

predecessor and succeeded in consolidating the republic, he was, in reality,

not that different. He increasingly championed centralisation of power and

nationalism but he faced stiff challenges. Some claimed that his presidency was

unconstitutional because Deodoro had failed to serve the statutory two years in

office and Floriano should, therefore, call a presidential election. His

solution to this problem was simply to retain the title of ‘Vice President’. He

also faced opposition from senior officers of the Brazilian navy who resented

the power and prestige of the army. Civil unrest raged in several states from

the north to the south of the country and in 1893 revolutionaries occupied

Santa Catarina and Paraná in Rio Grande do Sul, capturing the city of Curitiba.

Ultimately, though, they were ill-equipped for outright war. In 1893, Admiral

de Melo also acted against Floriano, once again threatening to bombard the

capital, but the president refused to follow the example of Deodoro by

resigning. By 1895, he had quashed the revolt in Rio Grande do Sul and had also

succeeded in pacifying the naval rebels.

In March 1894, Floriano called a presidential election,

following pressure from the Republicans running São Paulo who were providing

vital financial, military and political support to him. They sought to

safeguard national stability and unity and protect their state from an influx

of foreign investment and immigrants. The paulistas had helped Floriano by

founding the Partido Republicano Federal (Federal Republican Party) or PRF in

1893, but he was, of course, excluded by the constitution from standing for

election for a second term. Now eager to replace military rule with a civilian

leader from their own ranks, this coalition of senators and deputies from

several states put forward Prudente de Morais Barros as their presidential

candidate. This marked the end of political activity by the army for the time

being and Floriano’s subsequent death helped to further distance them from

politics. The rival 1894 presidential candidate from Minas Gerais, Afonso

Augusto Moreira Pena (1847–1909) lost heavily to Prudente – by 277,000 votes to

38,000 on 1 March 1894. It is worth noting, however, that with turmoil in Rio

de Janeiro at the time, civil disorder in three of the country’s southern

states and the severely restricted nature of the franchise, only 2.2 per cent

of the entire Brazilian population voted in this election.

The Rubber Boom

1879–1912

From the middle of the nineteenth century until the collapse

of the market in 1910, rubber was vitally important to the Brazilian economy, bringing

enormous profits to those involved in it. Natural rubber comes from a milky

white fluid called latex drained from the Hevea brasiliensis tree found in

abundance in the Brazilian state of Pará in the Amazon tropical rainforest.

Latex, found in sap extracted from the tree trunk through a small hole bored in

it, had been exploited by the native peoples for centuries, smoked over a fire

and molded into objects. In the late eighteenth century, the colonial

government was ordering boots made of latex from them but, until around 1830,

no one viewed it as having any real commercial potential. Towards the end of

that decade, however, British and North American scientists devised the process

of vulcanisation, in which the raw sap could be stabilised by heating. Soon,

rubber was being used in a variety of products such as tyres for bicycles and

motorcars and electrical insulation devices. Demand went through the roof and

before long entrepreneurs and immigrants were flooding into the Amazon region.

These rubber tappers extracted the sap before forming it into large balls of

rubber that were sold at local trading posts. It was then transported to the

coast before shipping to foreign ports.

As a result of the boom in demand for rubber, a number of

towns and cities grew astonishingly rapidly, populated by ‘rubber barons’ who

had amassed great fortunes. One example was the Amazonian port city of Manaus

which grew from just a few settlers to a bustling city of 100,000 by 1910. Its

famous opera house was constructed in 1881 by a local politician, Antonio Jose

Fernandes Júnior, who envisioned a ‘jewel’ in the heart of the Amazon

rainforest. It was the second Brazilian city, after Campos dos Goytacazes in

the state of Rio de Janeiro, to have electricity. Foreign capital was invested

in the region to create trading houses and companies, amongst which was the one

that built the Madeira-Mamoré railway, completed in 1912, which linked Brazil

and Bolivia. 6,000 workers are said to have lost their lives during its

construction.

By 1910, the Amazon’s pre-eminence in the production of

rubber was coming to an end. Several decades earlier, the Royal Botanical

Gardens in Kew in England had smuggled some rubber seeds out of Brazil and

produced trees in its hothouses in London. Seeds were then sent to the British

colonies of Ceylon (modern-day Sri Lanka) and Malaya (modern-day Malaysia)

where, unlike the Brazilian variety, they proved resistant to disease. They

also produced a more abundant crop. The American Ford Motor Company tried to replicate

what the British had done by creating rubber plantations at a place they called

Fordlandia near the town of Santarém in Pará but the South American trees’ lack

of immunity to disease led to failure and the British, with their efficient and

cost-effective Asian plantations, were left in control of the world’s rubber

market. The development of a synthetic substitute for natural rubber during

World War One caused further damage to the Brazilian rubber industry. Only when

the Allies were cut off from their Asian supplies during the Second World War

did Amazonian rubber see a brief revival.

The Paulista and

Café-Com-Leite Presidents

It could be said that the Brazilian First Republic was

little more than a search for the best type of government to take the place of

the monarchy, the argument alternating between centralisation and devolution of

power to the states. The instability and factional violence of the 1890s was a

result of the lack of agreement amongst the various elites about the most

appropriate government model. The Constitution of 1891 had given the states

considerable autonomy and, until the 1920s, the federal government was

therefore dominated by a combination of the most powerful states in the

Republic – Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro, Rio Grande do Sul and, of course, Sâo

Paulo.

Prudente’s first year in office saw the end of the Naval

Revolt and the uprising in Rio Grande do Sul, although he was criticised for

being too lenient to the Rio Grande do Sul rebels. In some quarters there was

still a hankering for the monarchy and defenders of the Republic such as the

ultra-national Jacobins, who had formed militia to defend Rio during the Naval

Revolt, warned of monarchist conspiracies. Their warnings seemed to have been

justified in 1896 as news reached the capital of a charismatic preacher,

Antônio Vicente Mendes Maciel (1830–97), nicknamed Conselheiro who, in 1893,

had assembled a community on an abandoned ranch at Canudos, a settlement 200

miles to the north of Salvador in Bahia. Conselheiro preached the return of the

monarchy, describing the republicans as atheists. In 1896, he was engaged in a

dispute with local officials over the cutting of timber that resulted in a

force of police officers being sent to Canudos. They were sent packing, leading

the Bahia Governor, Luís Viana (1846–1920), to request federal troops. Despite

being armed with artillery and machine guns, they, too, were defeated and their

commander was killed. The local dispute had quickly escalated into what became

known as the Guerra de Canudos (War of Canudos), threatening the fledgling

republic. There was protest and an outbreak of violence in Rio de Janeiro

before an even larger military force was dispatched to the Northeast,

consisting of 10,000 troops personally directed by the Minister of War, Marshal

Carlos Machado Bittencourt (1840–97). During the ensuing siege, Conselheiro

died, probably of dysentery, and Canudos was razed to the ground, more than

half its 30,000 inhabitants being killed in the fighting and its aftermath. This

‘monarchist threat’ had been defeated but at a cost to the reputation and

prestige of the army and of Prudente. The president’s unpopularity was made

clear when a young soldier, Marcelino Bispo (1875–98), tried to assassinate him

on 5 November 1897. Bittencourt, the Minister of War, died after being stabbed

protecting the president. When it emerged that Bispo had been encouraged in his

assassination attempt by the editor of the Jacobin newspaper, O Jacobino,

Prudente used the full force of the powers allocated to the presidency by the

1891 Constitution by coming down hard on Rio de Janeiro, especially the

Military Club, a haunt of the Jacobin army officers, which was shut down.

The next president, Dr Manuel Ferraz de Campos Sales

(1841–1913), governor of Sâo Paulo, was a paulista, like Prudente, emphasising

the stranglehold that the political elite of the major states had on the

country. To combat growing unrest in the states as well as factional fighting,

Campos Sales devised a strategy known as the ‘policy of the governors’ by which

a state’s parliamentary delegates would be connected to the dominant political

grouping in that state. As well as ending the factional fighting, he also hoped

this would enhance the power of the executive branch of the government. He

added to this by making the Chamber of Deputies more submissive to the

executive. Unfortunately for him, it was only partially effective.

The ‘policy of the governors’ also proved useful in dealing

with the Brazilian economy. Foreign debt inherited from the monarchy remained a

huge problem and military expenditure during the 1890s did not help the

situation. Between 1890 and 1897, the national debt increased by 30 per cent,

resulting in even greater indebtedness to foreign banks. It was not helped by a

fall in the price of coffee caused by abundant harvests in 1896 and 1897 that

meant less foreign exchange coming into the country. Campos Sales arranged a

funding loan that placed a great many difficult conditions on Brazil – all of

its customs income from the port of Rio de Janeiro were to go to its creditors

and further loans were prohibited until 1901. A programme of deflation also had

to be undertaken. In an attempt to balance the books, Campos Sales increased

federal taxes and introduced austerity measures, making his government very

unpopular. By such desperate means, Brazil was prevented from going bankrupt,

but the country would be hampered by these decisions for many years to come.

Making all this happen required the support of the legislature and, as

congressmen’s loyalties lay with the political leader of their state and their

parties, the president went directly to the state governors and the ruling

elites. Campos Sales made a promise not to intervene in the states’ internal

affairs and the governors made it all work by using the coronelismo system.

They provided positions and favours to the local coronéis who, in turn,

delivered votes at the municipal and federal elections.

The governors had a vested interest in maintaining this

system but that was dependent on the right man occupying the post of president.

They met before each election, therefore, to select a suitable candidate and

then ensured that he received enough votes. Naturally, the most powerful

states, especially São Paulo and Minas Gerais, being the wealthiest and also

possessing more citizens who satisfied the literacy requirement, were most

influential in this process. Furthermore, their state political parties were

far better organised than those of the other states. This way of manipulating

the political machine came to be known as café-com-leite (coffee with milk)

because of São Paulo’s connection with the coffee industry and Minas Gerais’

with milk. As a result, their candidates often achieved more than 90 per cent

of the vote. This was helped by the fact that the ballot was rarely private and

opposition was summarily dealt with. In this way, Brazil failed to develop a

healthy multi-party political system. But the ‘politics of the governors’

undoubtedly had the desired effect, producing political stability and

guaranteeing that the army would stay out of politics. As a system, however, it

differed little from the corrupt political system that had prevailed during

military rule and the Empire.

During his term of office Campos Sales succeeded in

maintaining peace and order and in improving the nation’s economic situation,

but the austerity measures he had imposed on the Brazilian people led to a rise

in the cost of living and made his government extremely unpopular. Nonetheless,

the ‘politics of the governors’ managed to deliver a third paulista president

in 1901 when Francisco de Paula Rodrigues Alves (1848–1919), governor of São

Paulo, romped home in the presidential election by 592,000 votes to Quintino

Bocaiúva’s 43,000. Rodrigues Alves was chosen because it was expected that he

would continue with the policies of Campos Sales. He had served as Minister of

Finance in the governments of both Floriano and Prudente and had a reputation

for financial expertise. He would also distinguish himself as a town planner,

launching a major undertaking to modernise Rio de Janeiro.

Towards the end of his term of office, Rodrigues Alves

proposed another São Paulo governor, Bernardino de Campos (1841–1915), as his

successor but this time there was resistance from the smaller states. At the

time, Rio Grande do Sul had been increasing in wealth and political status and

one of its senators was the charismatic and powerful José Gomes Pinheiro

Machado (1851–1915). For more than a decade, Pinheiro Machado, vice president

of the senate, dominated Brazilian politics. He led a group of congressmen

known as the Bloco, many of them from the less powerful northern and

northeastern states, who gained a voice through his leadership. Machado became

something of a ‘kingmaker’, as was proved in 1905 when he swung the votes of

his bloc behind Afonso Pena, from Minas Gerais, former vice president to

Rodrigues Alves. Afonso Pena won the election by 288,000 votes to a mere 5,000,

bringing to an end the run of paulista presidents. When it came time to decide

who would succeed him, Pinheiro Machado threw his voting bloc behind Marshal

Hermes Rodrigues da Fonseca (1855–1923) – known as ‘Hermes’ – nephew of the

Republic’s first president, Deodoro. Incumbent President Pena chose as his

nominee his finance minister, Davi Campista, another Minas Gerais politician

whom the paulista elite believed would continue with the policies of Pena’s

government. Campista’s candidacy came to an abrupt halt, however, with the

death of Pena in June 1909. Vice President Nilo Procópio Peçanha (1867–1924)

stepped into his shoes and then endorsed Hermes as presidential nominee for the

1910 election, to the dismay of the paulistas.

The election of 1910 was the first presidential election in

the history of the República Velha that was not decided from the outset. The

reason was the paulistas’ choice of the noted liberal Brazilian statesman, Rui

Barbosa, as a candidate to run against Hermes. After many years languishing in

the political wilderness, the former Finance Minister had risen to national and

international attention with his speeches in support of the rights of the

world’s smaller nations at the 1907 Hague Conference on International Peace

where he had gained the nickname the ‘Eagle of the Hague’. Barbosa railed

against the corrupt oligarchies that had been running Brazil and he was also

deeply concerned at Hermes’ candidacy, seeing it as an attempt by the army to

regain influence in government. He based his campaign on the simple choice

between civilian rule and military rule, claiming that if the marshal won,

Brazil would ‘plunge forever into the servitude of the armed forces’. (Quoted

in Documentary History of Brazil, E Bradford Burns, New York, Alfred A Knopf,

1967) The election was keenly fought, Rui Barbosa travelling widely to spread

his ideas for liberal reform. Hermes’ supporters were confident of victory,

with only São Paulo and Bahia lining up in favour of Barbosa. Army officers,

concerned at Barbosa’s anti-military stance, campaigned vigorously for Hermes

and in the end he won 233,000 votes, while Rui only managed 126,000. The

paulistas had been defeated in an election for the first time since 1894, even

though the winning margin was the narrowest to date.

It seemed that every military president was blighted by a

naval revolt and Hermes’ version occurred in November 1910, just a few days

after he had been sworn in as president. The mutiny on board two Brazilian

battleships was soon quashed but it was evident that the relative peace of the

last decade was at an end, a fact emphasised by a number of civil disturbances

around the country. Being a military man, Hermes was more prepared to send in

the troops than the civilian presidents before him, bringing rioters quickly

under control.

He was determined to avenge himself on the members of the

regional elites who had thrown their support behind Rui Barbosa in the 1910

election by replacing them with his own supporters. The army officers that he

sent in to overthrow these regimes described their work as política da salvacão

(politics of salvation) and there was a degree of irony in the fact that in

rooting out Hermes’ opponents, they were often also dealing with the

reactionary elements Rui had criticised during his election campaign. There was

serious fighting during this process, including the bombardment and invasion of

Salvador.

By this time, Pinheiro Machado’s Partido Republicano

Conservador (Republican Conservative Party) or PRC, created to take the place

of the Bloco in 1910, had begun to fall apart. He had also suffered during the

period of the política da salvacão because many of his people were the very

ones targeted by the army. Meanwhile, the paulista elite was determined to stop

Pinheiro becoming president in 1914. When the oligarchs of Minas Gerais

proposed their former governor Venceslau Brás (1868–1966), currently vice

president, as a candidate, the paulistas immediately gave him their

wholehearted support. Realising all was lost Pinheiro gave Brás his support but

ensured that his preferred candidate, the Maranhão senator Urbano Santos, was

selected as vice-presidential candidate. Brás was elected with an overwhelming

90 per cent of the vote. Pinheiro’s days as kingmaker were over and his

brilliant political career was brought to an abrupt halt by his assassination

in September 1915.

Brás‘s presidency was overshadowed by the outbreak of World

War One. Brazil was initially reluctant to go to war. After all, there were

large numbers of German immigrants in southern Brazil, many of whom were still

loyal to their homeland. The Brazilian foreign minister, Lauro Müller, also had

German antecedents. However, when Germany declared unrestricted submarine

warfare in the Atlantic, Brazil, as an Atlantic trading nation, became

involved. On 5 April 1917, the Brazilian ship Parana was sunk off the coast of

France and three crew members lost their lives. When news of the sinking

arrived in Brazil, riots broke out, an angry mob attacking German businesses in

Rio de Janeiro. Brazil eventually declared war on 26 October, after the

dismissal of Müller, Brazilian ships patrolling the South Atlantic and engaging

in mine-sweeping off the coast of West Africa. An Expeditionary Force was being

readied when the armistice was signed.

The 1918 election followed customary café-com-leite

guidelines and former paulista president, Rodrigues Alves romped home with 99

per cent of the popular vote. However, illness prevented the newly elected

president from taking office and he died the following year. It was decided to

hold a special election but the decision as to who would replace Rodrigues

Alves was a subject of debate between the elites of Minas Gerais and São Paulo.

Eventually, Epitácio Pessôa (1865–1942), a Paraíba senator and Minister of

Justice in the Campos Sales administration was selected. Pessôa was a delegate

at the Versailles Peace Conference that followed the end of the First World

War. In fact, he was still en route back to Brazil from the conference when the

election was held. Once again, Rui Barbosa stood and once again, despite

receiving almost 30 per cent of the vote, he was soundly beaten by the

candidate of the elites, by 286,000 votes to 116,000.

Pessôa made enemies and antagonised the military as soon as

he named his cabinet, appointing civilians to the ministries for war and the

navy. By this time, Hermes, who had been living in Europe, had returned to

Brazil where he was elected president of the Military Club in Rio de Janeiro.

He became a major critic of Pessôa, especially when the new president vetoed the

military budget. Pessôa faced still more criticism when it appeared that he was

giving preferential treatment to his own home region of the Northeast by

allocating 15 per cent of the federal budget to help install irrigation

projects to deal with the drought there.

But Pessôa was no more than an interim president. For the

1922 election, the elites of São Paulo and Minas Gerais chose the Minas Gerais

governor, Artur da Silva Bernardes (1875–1955). Once again, however,

café-com-leite caused anger amongst the other states – Pernambuco, Rio de

Janeiro and Rio Grande do Sul – who were never given a chance to nominate one

of their own. They formed a coalition, the Reação Republicana (Republican

Reaction) and threw their support behind Nilo Peçanha who had served briefly as

president of Brazil from 1909 to 1910 following the death of President Afonso

Pena. His campaign was based on claims that, under the café-com-leite system,

the other states of Brazil suffered from neglect. Of course, there was little

chance of defeating the ‘official’ candidate but some letters appeared in the

Correio da Manhã newspaper that were purported to have been sent by Bernardes

to a politician in Minas Gerais. They spoke disparagingly of Peçanha,

describing him as a ‘mulatto’ and calling Hermes da Fonseca an ‘overblown

sergeant’. Corruption amongst army officers was also mentioned. Although the

letters turned out to be forgeries, the army at the time accepted them as

genuine and put all their support behind Bernardes’ opponent Peçanha. In the

closest election in the history of the republic, Bernardes scraped in with 56

per cent of the popular vote. The elite had won again.

The disgruntled military now acted against the wishes of the

presidency. It had been Pessôa’s habit to order the army in where there were

problems with state elections, which Hermes believed was an abuse of power,

using the army for political ends. He sent a telegram to the commander of the

garrison at Recife suggesting that he resist any presidential directive to intervene

in situations involving local politics. When he was informed of this, Pessôa

was furious, immediately placing Hermes under house arrest and shutting down

the Military Club for six months. A couple of days later there was a mutiny at

Fort Copacabana in Rio de Janeiro that its participants said was aimed at

‘rescuing the army’s honour’. Government forces besieged the fort and bombarded

it by sea and by air. The following day, most of the mutineers surrendered but

a group of eighteen had resolved to fight to the death. They made their last

stand on the beach where sixteen of them were killed. Afterwards, a state of

emergency was declared, hundreds of cadets were expelled from the army school

and officers who had participated in the mutiny were posted to remote

garrisons.

The 1922 Revolt was the foundation for a movement involving

junior officers of the Brazilian army that became known as tenentismo as most

of those involved were lieutenants (tenentes). They believed that the Republic

would never achieve its full potential as a nation under civilian government

and demanded radical reform, both economically and socially to alleviate

poverty in Brazil. At the same time, however, the tenentes realised that there

was little hope of bringing down the regional oligarchies and party bosses

without the use of force and without that their movement never really

progressed into a full-blown political entity. Brazilian politics continued as

before.

As Bernardes took office, Brazil was in a parlous state,

embroiled in both economic and political crises. He added to the problems by

intervening in state politics – claiming he was merely trying to maintain law

and order – and often installing his own men where he could. He took his

revenge on the press by introducing censorship and refused to grant an amnesty

to those involved in the 1922 revolt. He courted even greater unpopularity with

a strict, conservative fiscal policy, demonstrated most vividly in his

withdrawal of financial support for the valorisation – manipulation of the

price – of coffee. He also withdrew funding for the irrigation projects that

Pessôa had launched during his term of office. So unpopular did Bernardes

become that he rarely left the presidential palace.

Finally, he faced a major crisis with what is called the

‘second Fifth of July’. On that date, two years to the day after the revolt of

1922, there was a better prepared uprising of young officers in São Paulo with

the aim of bringing down the Bernardes government. The leader was a retired Rio

Grande do Sul officer, General Isidoro Dias Lopes (1865–1949) and amongst other

prominent military figures involved were Eduardo Gomes (1896–1981), Newton

Estillac Leal (1893–1955), João Cabanas (1895–1974) and Miguel Costa

(1885–1959), the latter an important officer in the São Paulo Força Pública

(State Militia). They demanded the restoration of constitutional liberties and

denounced what they described as Bernardes’ excessive use of presidential

authority. They succeeded in taking control of the city for twenty-two days

until they were forced to withdraw. Other rebellions erupted in Sergipe,

Amazonas and Rio Grande do Sul. The São Paulo rebels left the city and headed

west, establishing their base in western Paraná and awaiting another force, led

by Captain Luís Carlos Prestes (1898–1990), that was marching north from Rio

Grande do Sul. The two groups joined up and marched into the interior of the

country, hoping to persuade the peasants to join with them in bringing

Bernardes down. For two years the Coluna Prestes (Prestes Column), as they had

come to be known, marched across the North and Northeast, fighting several

battles en route to Bolivia where they arrived and finally disbanded in 1927.

The ‘Prestes Column’ failed in its principal aim of bringing down the government

but it gained a huge amount of publicity and helped to make people aware of

rural poverty. Prestes became a Marxist in 1929, visited the Soviet Union in

1931 and, in 1943, after a number of years in prison, became leader of the

Brazilian Communist Party. Tenentismo carried on, seeking economic development

as a way to create social and political change in Brazil.

Café-com-leite continued unrelentingly and, in 1926, it was

the turn of the paulistas to come up with a candidate. After all, the last paulista

president, Rodrigues Alves, although elected in 1918, had fallen sick before

taking office which meant the last paulista actually to serve as president had

been the same politician during his first stint from 1902 to 1906. Washington

Luís (1869–1957), governor of São Paulo, was duly nominated by a meeting of

state governors, with Fernando de Melo Viana (1878–1954) of Minas Gerais as his

vice-presidential candidate. With Rui Barbosa now dead, there was little

opposition and it was an election marked by general apathy. Needless to say,

Washington Luís won 98 per cent of the vote.

One of the new president’s cabinet appointments had immense

importance for the future of Brazil – that of Getúlio Dornelles Vargas

(1882–1954) as Minister of Finance. The forty-three-year-old politician from

Rio Grande do Sul would become one of the most significant figures in Brazilian

history.