The “Battle on the

Ice”

Winters in northern Russia are long, and the surface of Lake Chudskoe

was still frozen when the Russian force marched out to meet the Germans, along

with their Finnish allies, on April 5, 1242. In a scene made famous for modern

filmgoers by the director Sergei Eisenstein, the invaders rushed at the

defending Russians, who suddenly surprised them by closing ranks around the enemy

and attacking them from the rear. The Russians scored a huge victory in the

“Battle on the Ice,” which became a legendary event in Russian history.

Two years later, Alexander drove off a Lithuanian invading force, and

though he soon left Novgorod, the people there had become so dependent on his

defense that they asked him to come back as their prince. With Novgorod now in

the lead among Russian states, Alexander was the effective ruler of Russia.

Prospects for a strong, well-defended Russian state had died

with the collapse of Kiev. Andrei Bogolyubsky, a grandson of Vladimir Monomakh

and architect of this latest defeat, transferred the center of power to his own

principality of Vladimir-Suzdal in central Russia. About this time, a small

settlement with the Finnish name of “Moskva” was established along the southern

border of the principality. Prince Andrei then attempted to put down the last

remaining challenge, Novgorod, the northern merchant city that had been

autonomous since 1136.

According to the Novgorodian Chronicle, miraculous

intercession saved the city: “There were only 400 men of Novgorod against 7,000

soldiers from Suzdal, but God helped the Novgorodians, and the Suzdalians

suffered 1,300 casualties, while Novgorod lost only fifteen men. . . .” After

several months had passed, Andrei Bogolyubsky’s troops returned, this time

strengthened by soldiers from a number of other principalities. The Chronicle

continues:

But the people of Novgorod were firmly behind their leader, Prince Roman, and their posadnik [mayor] Yakun. And so they built fortifications about the city. On Sunday [Prince Andrei’s emissaries] came to Novgorod to negotiate, and these negotiations lasted three days. On the fourth day, Wednesday, February 25th . . . the Suzdalians attacked the city and fought the entire day. Only toward evening did Prince Roman, who was still very young, and the troops of Novgorod manage to defeat the army of Suzdal with the help of the holy cross, the Holy Virgin, and the prayers of . . . Bishop Elias. Many Suzdalians were massacred, many were taken prisoner, while the remainder escaped only with great difficulty. And the price of Suzdalian prisoners fell to two nogatas [a coin of small value].

The political situation among Russia’s princes gradually

evolved into a balance of minor powers. Kiev’s last claim to dominance – its

special relationship with the seat of Orthodoxy – dissolved with

Constantinople’s fall to the crusaders of the Latin Church in 1204.

This decline of the Kievan state and the fragmentation of

Russian land into numerous warring principalities, none capable of leading a

united defense, coincided with the climactic last westward drive of Asiatic

hordes, led by the Mongols. Through military and economic vassalage, they were

able to halt Russia’s struggle toward nationhood for nearly 200 years.

Early in the thirteenth century, the scattered tribes of the

Mongolian desert – a mixture of Mongol, Alan, and Turkic peoples – were united

into a single fighting army that drove across the Eurasian plain, following the

paths of so many other Asian incursions, and threatened to change the course of

Christendom.

The leader who organized and led the nomads in their great

conquest of Asia was Temujin. He had been a minor chieftain whose success in a

series of intertribal wars on the vast steppe region of northern Mongolia had

united first his clan, then his tribe, and finally the majority of tribes –

including the Mongols. A kuriltai, or great assembly of chieftains, in 1206 had

proclaimed him not just the “Supreme Khan” but the “Genghis Khan,” meaning the

“all-encompassing lord.” Thenceforth his authority was understood to derive

from “the Eternal Blue Sky,” as the Mongols called their god.

Genghis Khan ruled over a people of extraordinary hardihood

and ferocity. The Mongols were tent-dwelling nomads whose horses were their

constant companions. Mongol boys learned to ride almost from birth, and at the

age of three, they began handling the bow and arrow, which was the main weapon

in hunting and in war. Their small sturdy horses were, like their riders,

capable of feats of great endurance. Unlike Western horses, Mongol ponies were

highly self-sufficient, requiring no special hay or fodder and able to find

enough food even under the snow cover. The Mongols took care of their horses,

which were readily rounded up in herds of 10,000 or more, allowing them regular

periods of rest; and on campaigns, each warrior was followed by as many as

twenty remounts. Their horses gave them the mobility to strike suddenly and

unexpectedly against their enemies. Furthermore, the Mongols were more skilled

in war than earlier nomad hordes, and they were undeterred by forest lands.

The Mongol nation numbered only 1 million people at the time

of the empire’s greatest extent. Within the empire, Turks and other nomadic

tribes were far more numerous, serving mainly in the lower ranks of the armies.

(The hordes that swept across Russia, under the minority rule of Mongols, were

predominantly Turkic and were generally known as Tatars, derived from the

European name for all the peoples east of the Dnieper.) The authority of

Genghis and of his law commanded unquestioning obedience. The Great Yasa,

compiled principally by Genghis, was the written code of Mongol custom and law,

laying down strict rules of conduct in all areas of public life – international

law, internal administration, the military, criminal law, civil and commercial

law. With few exceptions, offenses were punishable by death. This was the

sentence for serious breaches of military efficiency and discipline, for

possessing a stolen horse without being able to pay the fine, for gluttony, for

hiding a runaway slave or prisoner and preventing his or her recapture, for

urinating into water or inside a tent. Persons of royal rank enjoyed no

exemption from the law, except to the extent that they received a “bloodless”

execution by being put inside a carpet or rug and then clubbed to death, for to

spill a man’s blood was to drain away his soul.

The functioning of the military state was set forth mainly

in the Yasa’s Statute of Bound Service, which imposed the duty of life service

on all subjects, women as well as men. Every man was bound to the position or

task to which he was appointed. Desertion carried the summary punishment of

death. The Army Statute, which organized the Mongol armies in units of ten, was

explicit:

The fighting men are to be conscripted from men who are

twenty years old and upwards. There shall be a captain to every ten, and a

captain to every hundred, and a captain to every thousand, and a captain to

every ten thousand. . . . No man of any thousand, or hundred, or ten in which

he hath been counted shall depart to another place; if he doth he shall be

killed and also the captain who received him.

Even in the far-off khanates, which the Mongols eventually

established, the Great Yasa was known and revered much as the Magna Charta, of

about the same time, was regarded in England. It provided the legal foundation

of the Great Khan’s power and the means to administer the immense Mongol-Tatar

Empire from the remote capital, which he established at Karakorum.

In 1215, Genghis Khan captured Yenching (modern Peking) and

northern China; he went on to subdue Korea and Turkistan, and to raid Persia

and northern India. The famous tuq, or standard, of Genghis – a pole surmounted

by nine white yak’s tails that was always carried into battle when the Great

Khan was present – had become an object of divine significance to the Mongols

and of dread to their prey.

After taking Turkistan, gateway to Europe, Genghis Khan sent

a detachment of horsemen to reconnoiter the lands farther to the west. In 1223,

this force advanced south to the Caspian Sea and north into the Caucasus,

finally invading the territory of the Cumans, a Turkic people settled in the

region of the lower Volga. The khans of the Cumans called on the Russian

princes to help them. “Today the Tatars have seized our land,” they declared.

“Tomorrow they will take yours.” Heeding their call for aid, Prince Mstislav of

Galicia and a few lesser princes marched with their troops to rescue their

neighbor. In the battle on the banks of the Kalka River, at the northeastern

end of the Sea of Azov, the Cumans and their allies suffered disastrous defeat.

Few escaped with their lives, though Mstislav and two other captured princes

were saved for special treatment.

Chivalry required that enemies of high rank be executed

“bloodlessly” – according to the same rules as Mongol chieftains – so another

expedient was devised. The vanquished were laid on the ground and covered with

boards, upon which the Mongol officers sat for their victory banquet. The

Russians were crushed to death.

Apparently satisfied with their foray, the conquerors

vanished from southern Russia as suddenly and as mysteriously as they had

appeared. “We do not know whence these evil Tatars came upon us, nor whither

they have betaken themselves again; only God knows,” wrote a chronicler. Most historians

attribute their departure to political changes in Mongolia.

Genghis Khan died in 1227 while on a military campaign

against a Tibetan tribe. Since his eldest son and heir, Juji, had died earlier,

Genghis Khan’s son Ogadai was chosen to rule in Karakorum as Chief Khan.

However, Genghis directed that the administration of the empire was to be

divided among all his sons, each receiving a vast ulus, or regional khanate, a

portion of the empire’s troops, and the income of that area over which they

ruled.

Juji’s original share was to have been the khanate of

Kip-chak – the region west of the Irtysh River and the Aral Sea – most of which

was still unconquered. It was left to his son, Batu, to complete the mission.

In 1236, Batu, with the blessing of Ogadai, led a strong army westward. The

Mongols advanced by way of the Caspian Gate and then northwestward. They took

Bulgary, the capital of the Volga Bulgars, and making their way through the

forests around Penza and Tambov, they reached the principality of Ryazan. The

northern winter had already closed in, but Batu’s forces, some 50,000 strong,

were accustomed to harsh conditions. The snow-covered frozen lakes and

riverbeds served as highways for their mounts.

The Russians were in no position to defend themselves.

Kievan Rus was in decline, and the newer principalities, like Vladimir-Suzdal,

had not yet developed the strength to withstand such foes as the Mongols. Under

siege for five days, the town of Ryazan fell on December 21, 1237. A chronicler

described the ferocity of the Mongols:

The prince with his

mother, wife, sons, the boyars and inhabitants, without regard to age or sex,

were slaughtered with the savage cruelty of Mongol revenge; some were impaled

or had nails or splinters of wood driven under their finger nails. Priests were

roasted alive and nuns and maidens were ravished in the churches before their

relatives. No eye remained open to weep for the dead.

Similar stories were repeated wherever the Mongols ranged.

The invaders believed that their Great Khan was directed by God to conquer and

rule the world. Resistance to his will was resistance to the will of God and

must be punished by death. It was a simple principle, and the Mongols applied

it ruthlessly.

By February 1238, fourteen towns had fallen to their fury.

The whole principality of Vladimir-Suzdal had been devastated. They then

advanced into the territory of Novgorod. They were some sixty miles from the

city itself when suddenly they turned south and Novgorod was spared. The dense

forests and extensive morasses had become almost impassable in the early thaw,

and Batu decided to return with his warriors to the steppes, occupied then by

the Pechenegs. On their way south, they laid siege to the town of Kozelsk,

which resisted bravely for seven weeks. The Mongols were so infuriated by this

delay that on taking the town, they butchered all that they found alive,

citizens and animals alike. The blood was so deep in the streets, according to

the chronicler, that children drowned before they could be slain.

During 1239, Batu allowed his men to rest in the Azov region,

but in the following year, he resumed his westward advance. His horsemen

devastated the cities of Pereyaslavl and Chernigov. They then sent envoys to

Kiev, demanding the submission of the city. Unwisely, the governor had the

envoys put to death. Kiev was now doomed. At the beginning of December 1240,

Batu’s troops surrounded the city and after a few days of siege, took it by

storm. The carnage that followed was fearful. Six years later, John of Plano

Carpini, sent by Pope Innocent IV as his envoy to the Great Khan of Karakorum,

passed through Kiev. He wrote that “we found an innumerable multitude of men’s

skulls and bones, lying upon the Earth,” and he could count only 200 houses

standing in what had been a vast and magnificent city, larger than any city in

Western Europe.

The Mongols pressed farther westward and then divided into

three armies. One advanced into Poland; the central army, commanded by Batu,

invaded Hungary; the third army moved along the Carpathian Mountains into

southern Hungary. The Mongols were intent on punishing King Bela of Hungary

because he had granted asylum to the khan of the Cumans and 200,000 of his men,

women, and children who had fled westward in 1238. Batu had sent warnings,

which Béla had ignored. Now the Mongols overran the whole of Hungary, while the

northern army laid waste Poland, Lithuania, and East Prussia. They were poised

to conquer the rest of Europe, when suddenly, in the spring of 1242, couriers

brought news that the Great Khan Ogadai was dead. Batu withdrew his armies,

wishing to devote all of his energies to gathering support as Ogadai’s

successor. Western Europe was thus spared the Mongol devastation, which, had it

spread to the Atlantic, would have had an incalculable impact on the history of

Europe and of the world.

Ogadai had ruined his health, as he frankly admitted, by

continued indulgence in wine and women. Sensing death approaching, the khan

appointed his favorite grandson as successor. But Ogadai’s widow, acting as

regent until the boy was old enough to rule, plotted secretly to procure the

election of her own son, Kuyuk, although this was strongly opposed by Batu and

many other Mongol leaders.

Batu had established his headquarters at Sarai, some

sixty-five miles north of Astrakhan on the lower Volga. It was little more than

a city of tents, for the khan of the Kipchaks remained a nomad at heart, but

the splendor of his court became legendary among the princes of his realm.

Batu’s Golden Horde (from the Tatar altūn ordū) also impressed John of Plano

Carpini, who wrote:

Batu lives with considerable magnificence, having

door-keepers and all officials just like their Emperor. He even sits raised up

as if on a throne with one of his wives. . . . He has large and very beautiful

tents of linen which used to belong to the King of Hungary. . . . drinks are

placed in gold and silver vessels. Neither Batu nor any other Tatar prince ever

drinks, especially in public, without there being singing and guitar-playing

for them.

Though Batu owed allegiance to the Great Khan, he now

refused to visit Karakorum and to pay homage to Kuyuk. The Golden Horde

remained a province of the Mongol-Tatar Empire, but Batu and his successors

thenceforth administered the khanate with a large measure of independence,

particularly in its relations with Russia.

The Russian princes paid their tributes directly to Sarai.

The terror and destruction wrought by the Tatar invasion had left the Russians

stupefied and brought their national life to a standstill. Decades passed

before they began to recover, for the Mongol yoke lay heavy on them. In certain

regions, mainly in western Ukraine, the Mongols took over the administration

from the Russian princes and ruled directly; in other regions they set up their

own officials alongside the Russians and exercised direct supervision. In most

parts of Russia, however, the khan allowed the local Russian princes to

administer as before.

Before the Mongol invasions, a distinctly Russian system of

landholding and agricultural production had emerged. Feudalism, as it was known

in Western Europe, had not yet taken hold; with vast areas of Russia still open

to settlement, only the slaves were legally held to the acreage on which they

were born. Land was organized rather loosely in the hands of four principal

classes. First came the grand princes and lesser nobility, Russia’s

proliferating royal family. Beginning sometime in the tenth or eleventh

century, the princes turned from plunder and the collection of tributes to the

land as the primary producer of wealth. Yaroslav’s decision to divide Kievan

Rus into five portions, one for each of his sons, can be taken as the formal

beginning of the appanage system, by which titles and estates passed from

generation to generation.

Ranking below the appanage princes, and coming somewhat

later to land ownership, was the class of boyars, who were roughly equivalent

to the barons and knights of Europe. The boyars were an outgrowth of the

Varangian druzhina, the prince’s retinue, made up of a mixture of Scandinavian

and native Slavic leaders whose lands were secured by conquest, colonization,

or outright princely gift. In the tradition of adventurers, the boyars were

free to shift allegiance from one prince to another as it suited their own

interests. Initially, no contract, either formal or by custom, held the boyar

in vassalage to the prince, nor did a change of loyalty affect his title to his

land. Service was not a condition of ownership, and land passed from father to

son.

The Church formed the third and still later developing class

of landlords, its right to tenure and administration independent of the princes

established by Byzantine precedent. Church lands were acquired either by

colonization in unclaimed lands or by donations from princes, often in exchange

for the prayers of the Church.

The fourth and most elusive of definition was the peasant

majority. Conditions varied from one principality to another, depending on

local custom and the power of the prince. Prior to the development of boyars’

estates, a peasant held the land by virtue of having wrested it from the

wilderness. This he usually accomplished as a member of a commune – a gathering

of a few family units, itself an outgrowth of the more primitive Slavic tribal

family. The peasant was technically a free man and remained so until the reign

of Alexei, in the middle of the seventeenth century, though the intervening

centuries brought an accumulation of legislation that would progressively limit

his right to exercise this freedom. With the growing power of the various

landlord classes, however, peasants living in the more settled areas of Russia

were put under obligations, the most common being obrok, quitrent or payment in

kind for land use, and barshchina, payment in contracted days of labor on the

owner’s estate. Only the kholopy, or “slaves,” a motley assortment of prisoners

and indebted poor, were entirely excluded from landholding during the period of

Mongol domination.

The khans of the Golden Horde were interested in the

conquered lands only as a source of revenue and troops, and so were content to

allow the continuation of this political structure. The appanage princes had to

acknowledge that they were the khan’s vassals and that they recognized the

overall suzerainty of the Great Khan of Karakorum. They could hold their

positions only upon receiving the khan’s yarlyk, or patent to rule; often, they

first had to journey to Sarai to prostrate themselves before him. On occasion,

they even went to Mongolia to make their obeisances. Moreover, they had to

refer to the khan for resolution of major disputes with other princes and to

justify themselves against any serious charges, competing with each another for

the khan’s recognition with gifts, promises to increase their payments of

tribute, and mutual denunciations.

Prompt action was taken in each newly conquered country to

promote a census of the population, for the purpose of assessing the amount of

tax to be levied and the number of recruits owed to the army. Mongol officials

were appointed to collect and to enroll recruits. Delays in making payments to

the tax collector, or producing men, or rebellion of any kind were punished

with extreme ferocity.

Nevertheless, driven beyond endurance by Mongol demands, the

Russians sometimes rebelled. No fewer than forty-eight Mongol-Tatar raids took

place during the period of the domination of the Golden Horde, and some of

these expeditions had the purpose of suppressing the Russian uprisings.

Gradually, however, the khan’s grip on his vassal states relaxed. Early in the

fourteenth century, Russian princes were allowed to collect taxes on behalf of

the Horde, and the tax collectors and other officials were withdrawn. The

Russian lands once again became autonomous, though they continued to

acknowledge the suzerainty of the khan. However, internal rivalries, much like

those that had fractured the Russian principalities, were weakening the Golden

Horde, which was ceasing to display the bold confidence of conquerors. In the

fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, the khan’s direct rule came to be

limited to the middle and lower Volga, the Don, and the steppelands as far west

as the Dnieper.

The impact of the Mongol invasion and occupation on Russia’s

social and cultural fortunes was largely negative, halting progress and

introducing a number of harsh customs. The Mongols probably left their mark in

such evil practices as flogging, torture, and mutilation, the seclusion of

women of the upper classes in the terem, or the women’s quarters, the cringing

servility of inferiors, and the arrogant superiority and often brutality of

seniors toward them. But evidence that the invaders made any enduring, positive

impression is slight. Historians S. M. Solovyev and V. O. Klyuchevsky argued that

Russia had embraced Orthodox Christianity and the political ideas of Byzantium

two centuries before the coming of the Mongols, and its development was too

deeply rooted in Byzantine soil to be greatly changed. Further, the Mongol

conception of the Great Khan’s absolute power was, in practice, close to the

Byzantine theory of the divine authority of the emperor, and, indeed, the

Mongol and Byzantine concepts might well have merged in the minds of the

Russian princes.

Only the Orthodox Church flourished. The religion of the

Mongols was a primitive Shamanism in which the seer and medicine man, the

shaman, acted as the intermediary with the spirit world. He made known the will

of Tengri, the great god who ruled over all the spirits in heaven. This form of

worship could readily accommodate many faiths, and the Mongols showed a

tolerance toward other religions, which Christian churches would have done well

to emulate. The Mongols were familiar with Nestorian Christianity, a heretical

sect for which Nestorius, patriarch of Constantinople, was deposed in the fifth

century, and certain clans had embraced Nestorianism. Though the Great Khan,

after considering Buddhism, Christianity, and Judaism, had finally in the

fourteenth century decided to adopt Islam as the faith of the Mongols, they

continued to show a generous tolerance toward the Christians.

The Russian Orthodox Church, in fact, enjoyed a privileged

position throughout the period of the Mongol yoke. All Christians were

guaranteed freedom of worship. The extensive lands owned by the Church were

protected and exempt from all taxes, and the labor on Church estates was not

liable to recruitment into the khan’s armies. Metropolitans, bishops, and other

senior clerical appointments were confirmed by the yarlyk, but this assertion

of the khan’s authority apparently involved no interference by the Mongols in

Church affairs.

Under this protection, the Church grew in strength. Its

influence among the people deepened, for it fostered a sense of unity during

these dark times. Both the black, or monastic, clergy and the white clergy,

which ministered to the secular world and was permitted to marry, shared in

this proselytizing role. Moreover, the Church preserved the Byzantine political

heritage, especially the theory of the divine nature of the secular power. In

accordance with this tradition, the support that the Church gave to the

emerging grand princes of Moscow was to be of importance in bringing the

country under Moscow’s rule.

The Orthodox Church was also strengthened, by virtue of

being unchallenged by other ideas and influences. Kievan Rus had maintained

regular contact with the countries to the south and west. By the great trade

routes, Russian merchants had brought news of the arts and cultures, as well as

the merchandise, of these foreign lands. But the Mongol occupation had isolated

the Russians almost completely. The great ferment of ideas in the West, leading

to the Renaissance, the Reformation, the explorations, and the scientific

discoveries, did not touch them. The Orthodox Church encouraged their natural

conservatism and inculcated the idea of spiritual and cultural self-sufficiency

among them. Indeed, this isolation, which was to contribute notably to Russia’s

backwardness in the coming centuries, was to be one of the most disastrous

results of Mongol domination.

Only the remote, northern republic of Novgorod had managed

to escape the devastation of Batu’s westward advance in 1238. The city,

standing on the banks of the Volkhov River, three miles to the north of Lake

Ilmen, in a region of lakes, rivers, and marshes, had built up a commercial

empire “from the Varangians to the Greeks,” as they described it. “Lord

Novgorod the Great,” the Novgorodtsi’s title for their republic, had been one

of the first centers of Russian civilization. Beginning with Prince Oleg’s rule

in the last years of the ninth century, it had acknowledged the primacy of

Kiev; but as the power and prestige of “the mother of Russian cities” declined,

Novgorod had asserted anew its independence. In 1136, its citizens had rallied

and promptly expelled the Kiev-appointed prince who, they complained, had shown

no care for the common people, had tried to use the city as a means to his own

advancement, and had been both indecisive and cowardly in battle. The city

concentrated its efforts on commerce, especially its connections with the

Hanseatic trading ports of the Baltic, avoiding most of the internecine strife

that had wracked the other principalities. “Lord Novgorod” showed the same

pragmatism in dealings with the khan.

The Novgorodian Chronicle relates that their prince,

Alexander Nevsky, son of Yaroslav I of Vladimir, had recognized the futility of

opposition and had directed his people to render tribute. In the year 1259,

“the Prince rode down from the [palace] and the accursed Tatars with him. . . .

And the accursed ones began to ride through the streets, writing down the

Christian houses; because for our sins God has brought wild beasts out of the

desert to eat the flesh of the strong, and to drink the blood of the Boyars.”

Nevsky also made frequent journeys of homage to the khan of

the Golden Horde, at least once to distant Karakorum, and had won the trust of

the Mongols. But a further reason, which was perhaps of overriding importance

in gaining the khan’s favor, was that Mongol policy stimulated Baltic trade,

for international commerce was the source of the Golden Horde’s prosperity.

While Kiev lay in ruins, Novgorod’s trade in the Baltic, and south by the river

road to the Caspian Sea, continued to flourish, and the people – 100,000 in its

heyday – to prosper. Confident in their wealth and power, the citizens asked

arrogantly: “Who can stand against God and Great Novgorod?”

Novgorod was unique in claiming the right to choose its own

prince; it allowed him only limited authority, in effect keeping him as titular

head of state with certain judicial and military functions. The real power

emanated from the veche – an unwieldy but relatively democratic assembly of

male citizens – and its more select, more operative council of notables, which

such day-to-day business as taxation, legislation, and commercial controls.

Participation in the veche was by class – groups of boyars, merchants,

artisans, and the poorer people – with the aristocratic element generally

dominant by virtue of its close ties with the council. Conflicts within the

assembly were often violent – a unanimous vote was required to pass any

decision – and meetings broke up in disorder. Nevertheless, they managed to

elect their posadnik, or mayor, and tysyatsky, or commander of the troops. The

veche also nominated the archbishop, who played an influential part in the

secular affairs of the republic. Both council and veche had existed in Kievan

Rus as advisory institutions, but in Novgorod, they represented an impressive,

if short-lived, experiment in genuine democratic government.

Prince Alexander was one who seems to have enjoyed the good

will of his electors. He had an equally successful record in dealing with the

armed threat from the West. While the Russian lands were falling under

Mongol-Tatar occupation, powerful forces were putting pressure upon the Western

principalities. In 1240, Alexander routed the Swedes on the banks of the Neva

River, thereby gaining for himself the name “Nevsky” and for the Novgorodtsi an

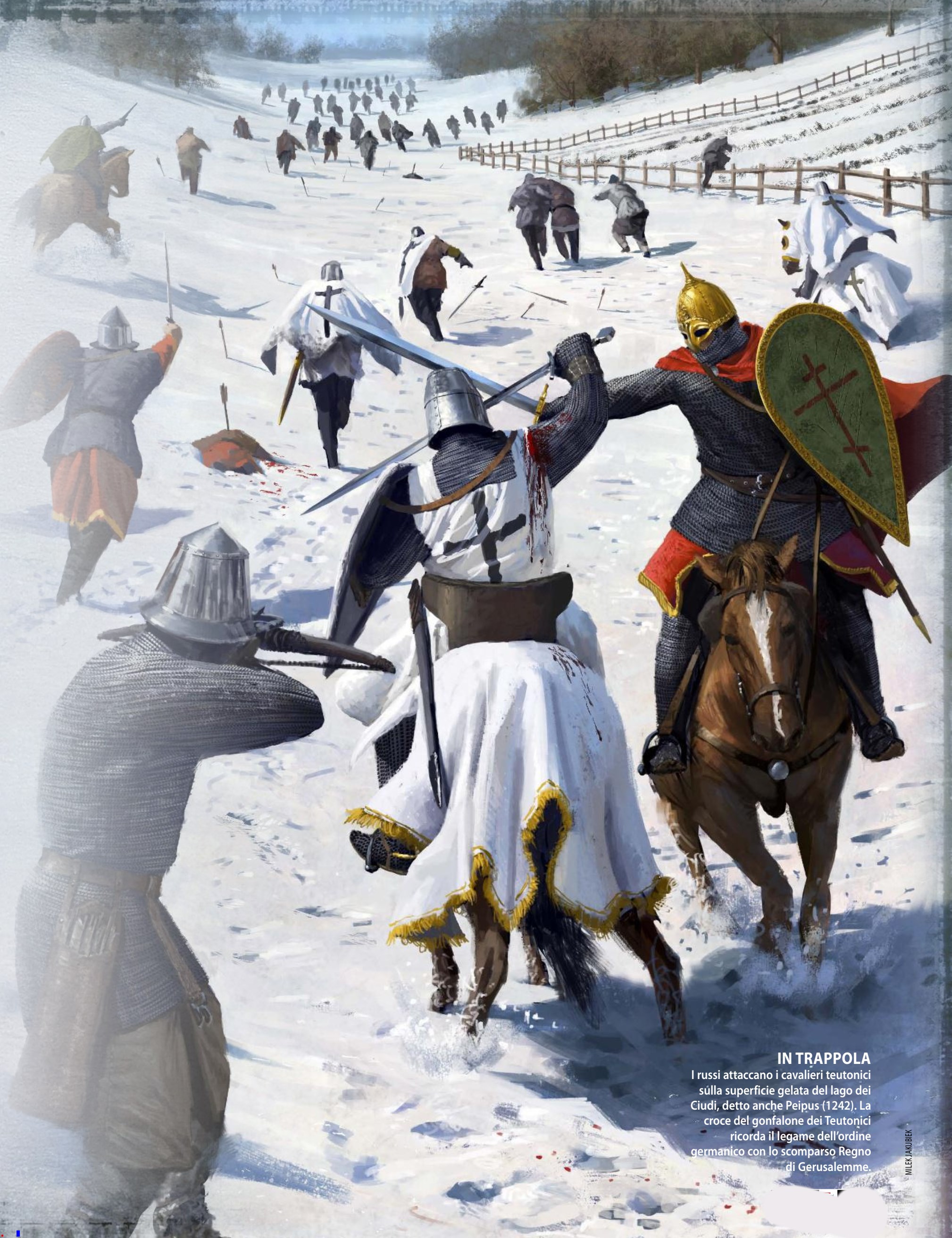

outlet to the Baltic. Two German military religious orders, whose conquests

were directed at the extension of Roman Catholicism among the pagan Letts and

Livonians of the Baltic, were also major threats. First to be organized were

the Teutonic Knights, an army of noblemen that had come into existence as a

hospital order during the third crusade. Beginning in the thirteenth century,

they took over lands roughly equivalent to later-day Prussia. At this time, a

second order, the Livonian Knights, was founded by the bishop of the Baltic

city of Riga. The two united in 1237, and five years later, they marched on

Novgorod. They were met on the frozen Lake Peipus, near Pskov, and defeated in

the Battle on Ice, thus halting for a time the German drive eastward.

The Knights continued, however, to harass the pagan Letts

and Lithuanians, who were forced to reach out in the only direction left them:

eastward toward their weakened neighbor Russia. The Mongols had ravaged

Lithuania in 1258, but had then withdrawn and not returned. The Lithuanians had

recovered quickly, and not long afterward, under their great military leader

Gedimin the Conqueror (1316-41), they succeeded in occupying most of west and

southwest Russia, including Kiev. Though technically it now lay outside the

sphere of Russia proper, this new “grand princedom of Lithuania and Russia”

would rival the strongest all-Russian principality for decades to come.

Olgierd, the son and successor of Gedimin, eventually defeated Novgorod in

1346, thereafter subduing the sister city of Pskov, expelling the Tatars from

southwest Russia, and taking the Crimea.

Meanwhile, Moscow was growing from an insignificant

settlement into the matrix and capital of the nation. Of this dramatic and

unexpected development in Russia’s history, a Muscovite would write in the

seventeenth century: “What man could have divined that Moscow would become a

great realm?” The chronicle relates that, in 1147, Prince Yury Dolgoruky of

Vladimir-Suzdal sent a message to his ally, Prince Svyatoslav of

Novgorod-Seversk: “Come to me, brother, in Moscow! Be my guest in Moscow!” It

is not certain that the town was then on its present site. Prince Yury founded

the town of Moscow nine years later by building wooden walls around the high

ground between the Moskva River and its tributary, the Neglinnaya, and thus

created the first kremlin, or fortress. It soon became the seat of a family of

minor princes under the hegemony of Vladimir-Suzdal. In 1238, the Mongols

destroyed Moscow and the surrounding territory. About 1283, Daniel, son of

Alexander Nevsky, acquired the principality and became the first of a regular

line of Muscovite rulers. The rise of Moscow had begun.

Among Moscow’s neighbors, Tver, Vladimir-Suzdal, Ryazan, and

Novgorod were more powerful and seemed stronger contenders for leadership of

the nation, but Moscow had important advantages. It stood in the region of the

upper Volga and Oka rivers, at the center of the system of waterways extending

over the whole of European Russia. Tver shared this advantage to some extent,

but Moscow was at the hub. This was a position of tremendous importance for

trade and even more for defense. Moscow enjoyed greater security from attacks

by Mongols and other enemies. As a refuge and a center of trade, the new city

attracted boyars, merchants, and peasants from every principality, all of whom

added to its wealth and power.

Another important factor in Moscow’s development was the

ability of its rulers. They do not emerge as individuals from the shadowed

distance of history, but all were careful stewards of their principality – enterprising,

ruthless, and tenacious. They acquired new lands and power by treaty, trickery,

purchase, and as a last resort, by force. In a century and a half, their

principality would grow from some 500 to more than 15,000 square miles.

Ivan I, called Kalita, or Moneybag, who ruled from 1328 to

1342, was the first of the great “collectors of the Russian land.” Like his

grandfather Alexander Nevsky, he was scrupulously subservient to the Golden

Horde. His reward was to obtain the khan’s assent to his assuming the title of

grand prince and also to the removal of the seat of the metropolitan of all

Russia from Vladimir to Moscow, an event of paramount importance to Moscow’s

later claims of supreme authority.

Ivan I strengthened his city by erecting new walls around

it, He built the Cathedral of the Assumption and other churches in stone. The

merchant quarter, the kitai gorod, expanded rapidly as trade revived. Terrible

fires destroyed large areas of the city, but houses were quickly replaced, and

Moscow continued to grow.

Ivan I was succeeded by Simeon the Proud, who died twelve

years later in a plague that devastated Moscow. He was, in turn, succeeded by

his brother, Ivan II, a man whose principal contribution to Russian history

seems to have been fathering Dmitry Donskoy, who became grand prince of Moscow

in 1363. Under Prince Dmitry’s reign, Moscow took advantage of the waning power

of the Golden Horde to extend its influence over less powerful principalities.

Generous gifts to Mamai, the khan of the Golden Horde, put an end to Dmitry’s

most serious competitor, Prince Mikhail of Tver; Dmitry’s patent was confirmed

and Mikhail’s claims to the throne ignored for several years. Then, with

Moscow’s power growing at an alarming rate, Mamai reversed his earlier grant

and sent an army against Moscow in 1380.

Dmitry was well prepared. He had rebuilt the Kremlin walls

in stone, adding battlements, towers, and iron gates. He had secured by treaty

the promise of support troops from other principalities. He had introduced firearms

on a limited scale. Dmitry won enduring fame by launching the first

counterattack against the dreaded Mongol enemy. The heroic battle of Kulikovo,

fought on the banks of the river Don (hence Dmitry’s surname “Donskoy”) ended

with the Russians inflicting a major defeat on the Golden Horde. The news was

greeted with great rejoicing in Moscow, though the Russians had lost nearly

half of their men in the struggle. It inspired all Russians with a new spirit

of independence. The battle was not decisive, however, and it brought

retribution. In 1382, the Mongols, this time led by the Khan Tokhtamysh, laid

siege to Moscow. For three days and nights, they made furious attacks on the

city, but they could not breach the stone walls. The khan then gained entry by

offering to discuss peace terms. Once inside the city, his warriors began to

slaughter the people – “until their arms wearied and their swords became

blunt.” Recording these events, the chronicler lamented that “until then the

city of Moscow had been large and wonderful to look at, crowded as she was with

people, filled with wealth and glory . . . and now all at once all of her

beauty perished and her glory disappeared. Nothing could be seen but smoking

ruins and bare earth and heaps of corpses.” More than 20,000 victims were

buried. With extraordinary vitality, however, Moscow soon was revived, and

within a few years had been restored to its former power.

In the reign of Dmitry’s son, Vasily I, Moscow was

threatened with an attack by Tamerlane, the Turkic conqueror who had, by a feat

of historical revisionism, claimed to be a descendant of Genghis Khan. In 1395,

following his successful campaign against his rivals, the doubting Tokhtamysh

and the Golden Horde, Tamerlane advanced from the south to within 200 miles of

Moscow, but then turned aside, apparently convinced that another siege would be

too costly to his own troops. The city was saved, the people said, because of

the miraculous intervention of the icon of Our Lady of Vladimir.

Though the Tatars would continue to be a major factor in

Muscovite history for another half century, the balance of power was shifting

to the Lithuanian front. Ladislas Jagello, son of the Lithuanian grand duke who

had brought parts of western Russia under his suzerainty, ascended the

Lithuanian throne in 1377. During the Jagello era, which his reign inaugurated,

the prince conceived a dynastic union with his former enemy, Poland, through

marriage to Jadwiga, heiress to that throne. Jagello thus became sovereign of

the federated states of Poland and Lithuania, the latter under the vassal rule

of his cousin. Husband and wife shared an ambition to control a still larger

portion of Russia. Jagello’s conversion to Roman Catholicism, which was part of

the marriage treaty, made this imperial plan all the more dangerous to

Muscovite security. With Smolensk’s fall to the Lithuanians in 1404, almost all

of the lands on the right bank of the Dnieper were brought under

dynastically-united Polish and Lithuanian rule.

Only a matter as crucial to all Slavic peoples as the defeat

of the Teutonic Knights held them in a brief state of peace. In 1410, the

combined Polish and Lithuanian forces met the German forces at Tannenberg.

Their grand master, many of their officers, and a devastating number of knights

fell in the bloody clash. The eastward drive of the German Knights was

effectively halted for all time, but the Polish and Lithuanian drives received

new impetus.

The reign of Vasily I ended in 1425. His son and successor,

Vasily II, ascended the Muscovite throne against strong opposition from a

powerful boyar faction; the first twenty-five years of his long reign were

largely devoted to suppressing these rivals, a feat achieved only after he had

himself been blinded. Events outside of Muscovy would be of more lasting

significance: The Golden Horde was losing large parts of its territory to the

breakaway khanates of Crimea and Kazan, and the Ottoman Turks were threatening

the very existence of the Greek Orthodox Church. In a desperate move to defend

itself from total destruction, the Eastern clergy had sought help in Rome, at

the price of recognizing the supremacy of the pope. Moscow was represented at

the Council of Florence, which met in 1439, by the Russian Metropolitan

Isadore. Acting on his own initiative, Isadore committed Russian Orthodoxy to

the bargain. Upon his return, he was deposed and arrested, and Moscow formally

severed its ties with Byzantium. When Constantinople, the capital of Eastern

Orthodoxy, fell to the Turks in 1453, no Russian was surprised. It was God’s

retribution to the duplicitous Greeks. Holy Russia would find its own way.