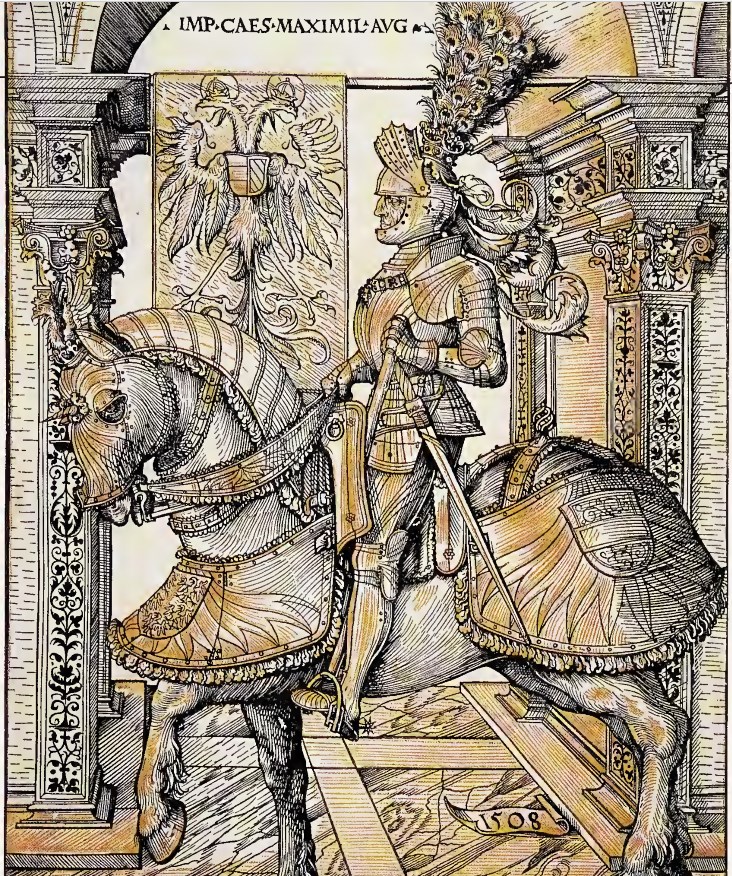

Maximilian I on Horseback, Hans Burgkmair the Elder (1473-1531),

German, 1508. Modern arms scholars have named a characteristic form of

sixteenth-century armor after Maximilian I, which appears in Hans Burgkmair’s

masterful engraving of the emperor. This armor combines the smooth, round

shapes of Ifalian armor with the rippled flutes of Germanic armor. The

culmination of a transition that began late in the fifteenth century,

Maximilian armors typically have crisply defined vertical fluting on their

major components, except for the lower leg defenses. This fluting corresponds

to the style of civilian male fashion, mimicking in steel the effect of a cloth

outer garment cinched by a waist belt-just as the long, pointed foot defenses

of Gothic armor copied contemporary footwear. The breastplate itself is well

rounded, like the civilian cloth doublet, and the foot defenses are broad-toed

in the manner of early sixteenth-century shoes. Like corrugation, the fluting

added rigidity without increased weight. This fluted fashion was, however, more

complicated to produce, and was generally not popular outside of German lands.

It peaked around 1525 and was rarely seen by the late 1530s, although it

occasionally resurfaced after that time.

Mail shirt, Western European, sixteenth century. The most common form

of metal body armor during the medieval period was mail, an interlocking,

closely spaced network of riveted and solid rings, usually of iron, although

brass was occasionally employed for decorative effect along the bortiers. Used

in the Battle of Hastings and the Crusades, its name is derived from the Old

French word maille, meaning “mesh.” Worn over a cushioned

undergarment known as an aketon or haqueton, mail provided a reasonably

effective defense against lighter cutting weapons, but offered little

resistance to the crushing blows of heavier arms such as clubs and axes. To

defend himself against such blows, the warrior carried a wooden, leather-covered

shield on his nonsword arm. Other disadvantages of mail included its tendency

to bunch up at the joints and the heavy weight it placed on the shoulders. The

mail shirt shown here weighs approximately seventeen pounds.

Mail was replaced by plate armor as the primary form of European body

defense during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, but continued to serve

as secondary protection for areas like the armpits and groin. It was also used

by foot soldiers, who could not afford, or did not wish to use, a more

expensive, restrictive plate harness.

Detail of mail shirt. Western European, sixteenth century. Mail is a

network of interlocking iron or steel and occasionally brass rings whose density

and tight construction created a surface quite resistant to the sharp edges of

cutting weapons. The flexible nature of mail, however, meant that it offered

little protection from the impact of crushing blows, a problem only

satisfactorily addressed by the adoption of plate defenses.

Detail of a sabaton, possibly by Wolfgang Großschedel

of Landshut (active c. 1521-1563), German, 1550/60. Tills foot defense is

believed to be part of an armor belonging to Wilhelm V, Duke of Jülich,

Cleve, and Berg (1516-1592). This sabaton, which mimics the shape of

contemporary shoe styles, would have been worn over leather footwear.

Detail (proof mark) of three-quarter cuirassier armor, Italian, 1605/10.

Generally speaking, elements of battlefield armor underwent strenuous testing

with weapons. If a breastplate, for example, were meant to resist bullets, it

would be shot at from close range. The resulting dent, or “proof mark,

demonstrated that an armor was of high quality.

During the Middle Ages, armor production became an important

and rapidly growing facet of European trade and commerce. Armorers were members

of craftsmen’s guilds, which set very rigid standards to insure a high-quality

product. The guilds also enforced regulations to control the work environment;

these rules, however, varied across Europe and even from city to city.

Much of what we know about the working life and craft

techniques of the armorer has been gleaned from surviving objects, documentary references,

inventories of tools and appliances, and a handful of pattern-books and design

drawings. Most of this material concerns a rather small number of makers and

shops in Germany and Italy.

The heart of armor manufacture for much of the fifteenth century

was Italy, particularly Milan, whose armorers were highly regarded throughout

Europe. While a great deal of material was produced at other centers across the

continent, it paled in comparison to the quantity and quality of pieces coming

from the Italian workshops. Individual Italian armorers specialized in certain

components of body armor and provided these prefabricated items under contract

to others who would assemble the final products.

Brescia was also a major center of Italian arms production.

Indeed, at one point Brescia had some two hundred workshops (botteghe), each

with a master and three or four assistants. Furthermore, colonies of Italian

armorers existed in France and the Low Countries. The armor ordered by the

dauphin Charles (later Charles VII) of France for Joan of Arc is said to have

been made by a Milanese armorer in Tours. Italianate style was widely imitated

throughout fifteenth-century Europe, and much material was exported from Italy

to England, Spain, and Germany.

By the end of the fifteenth century, German armorers began to

cut into Italy’s near monopoly, and for the next century and beyond they more

or less dominated the industry. Important centers were located in Augsburg,

Cologne, Landshut, and Nuremberg.

Nuremberg provides a good case study for understanding the

relationship between the individual armorer, his trade, his city, and commerce.

Unlike their counterparts elsewhere, Nuremberg’s armorers did not belong to a

trade guild, having lost this privilege following a general revolt of craftsmen

in 1348-49. As a result, they had to select “small masters” to

represent them on the city council and to inspect their manufactured goods.

Further, the armorers were classified as those who worked with plate armor

(Plattner) or mail (Panzermacher). Each master was permitted two journeymen and

four apprentices, whose numbers could be increased only with the approval of

the city council.

To reach the status of complete master armorer, an applicant

had to prepare four ”masterpieces” (Meisterstiicke) upon finishing his

apprenticeship, which five designated masters reviewed. Further, he had to

provide an item for each area of armor making in which he wished to produce

objects-for example, helmet, cuirass, arm and leg defenses, and gauntlet.

Unlike in some other cities, in Nuremberg the applicant could not fashion a

single armor containing the prerequisite pieces, but had to make each element

separately. Following the masters’ evaluation, the armorer could only produce

armor in those areas in which his masterpieces had passed inspection. If less

than totally qualified, he would have to work in concert with other qualified

masters to fill orders for full armors. If he passed the exam, however, the new

master had his personal maker s mark recorded by the city. The city did permit

some less-exacting production, but such materials were specially identified so

they would not diminish the high production standards of first-rate Nuremberg

output.

It is noteworthy that Nuremberg long recognized the great

commercial potential of a thriving arms industry. The greater part of the

makers’ output was in “munitions-quality” material (what today we

would probably refer to as government-issue), a designated amount of which went

to the city’s garrison.

The reputation of European armorers for high-quality,

reliable production was affected not only by their expertise and standards, but

also by the raw materials they used. At great expense, many armorers sought

iron from the finest ore reserves in Europe, located in Austria around

Innsbruck and the southeastern province of Styria. After being extracted, iron

was transformed into thick plates called blooms, which the armorers then

imported.

Tailor-made, high-quality armors required the client’s

dimensions, which could be obtained from his clothing, or an existing arming

doublet-the wearer’s padded textile “undergarment.” The armorer might

also obtain wax casts of the limbs, or, ideally, take the client’s measurements

directly. While no actual patterns for armors appear to have survived, scholars

presume that they did exist. Indeed, to prepare for the production of large

munitions-quality orders of nearly identical elements, an armorer probably made

templates in varying sizes.

The raw plates were cut to shape with huge shears, heated,

and roughly formed by hammermen. The actual armorers then received these

plates, shaping them into elements with hammers, anvil irons, stakes, and other

tools. Throughout the process, the armorer had to remain alert to the physical

changes taking place in the piece he was crafting. Because hammering often made

the metal brittle, the piece was heated, or annealed, from time to time, and

was sometimes treated with chemicals. Annealing was done sparingly, for too

much heat tended to weaken the plates. The armorer had to constantly bear in

mind each element’s function and placement in order to insure that it was

adequately thick where necessary and thinned out wherever possible to reduce

weight. The finished element had an extremely hard surface with a more

malleable interior. Throughout manufacture, pieces were examined, test- fitted,

and, in some cases, viewed by outside inspectors.

Many decorative techniques were available for ornamenting

arms and armor. These skills were often passed from one family member to

another, as armorers and decorators wanted to keep their lucrative trade

secrets in the family. Virtually all of the methods employed in the manufacture

of contemporary European decorative arts were practiced by armorers at one time

or another. Surfaces were fire-blued and gilded, painted, alternately decorated

with black-painted surfaces and polished sections (to produce

“black-and-white” armor), enameled, chased and engraved, embossed,

fitted with applique, damascened, and encrusted with precious metals and gems.

The most typical decorative technique was acid-etching, since it facilitated

the transfer of finely rendered designs to the surface of the armor. This

technique was then enhanced by the gilding or blackening of etched surfaces.

Goldsmiths embellished arms and armor with sumptuous

precious metal for use in pageants. They also probably produced and attached

cloth-of-gold coverings to extremely fine brigandines. The virtuoso goldsmith

Wenzel Jamnitzer of Nuremberg made a set of silver saddle plates for Emperor

Maximilian II, using motifs from the decorative arts objects made in his

workshop. Generally speaking, no artist viewed the decoration of arms and

weaponry as unworthy of his skills. As a result, the designs incorporated in

arms and armor often display great creativity and finesse.

Once all armor elements were decorated, armor assembly

entered its final phase, which involved the work of locksmiths. These men

fitted the strapping, buckles, hinges, and other parts. After it was inspected

and accepted, the armor was often stamped with the mark of its maker. In

addition, the mark of the city where the armor was made was often punched into

the surface, indicating that the piece met local standards for quality. Several

additional types of markings appear on armors, including those of the mills

that provided the rough plates, assembly marks, external serial marks to

prevent the mix-up of very similar pieces, and arsenal numbers.

The true test of an armor of course was how successfully it

functioned and how pleased the new owner was with his purchase. Only the most

fortunate armorers found their clients as satisfied as Emperor Charles V was

after trying on an armor made by Caremolo Modrone of Mantua: “His Majesty

said that they [his armor elements] were more precious to him than a city. He

then embraced Master Caremolo warmly … and said they were so excellent

that… if he had taken the measurement a thousand times they could not fit

better…. Caremolo is more beloved and revered than a member of the

court.”