The Early Tang:

Challenges and Successes

Seizing on the Sui disasters, Li Yüan, a high-ranking Sui

general, rose against the emperor and went on to establish the Tang dynasty.

The men under his command on the day of his revolt totaled roughly 30,000, both

infantry and cavalry. Like many of the generals who hoped to replace the Sui,

he was able to enlist the aid of several thousand Turkish cavalrymen. By the

time Li Yüan had captured the city of Changan, which was proclaimed the Tang

capital, he had picked up an additional 200,000 men. Many of these were men who

had deserted the Sui army during and after the disastrous Korean campaigns. Li

Yüan divided this force into twelve divisions, each led by a trusted general,

for there was still much fighting to come before China was securely in Tang

hands.

These were true divisions, expected to be able to operate on

their own with a full complement of various types of weapons and soldiers, both

infantry and cavalry. In addition, the soldiers were allotted lands on which

their families were to be settled. The production of these lands was to make

the divisions self-sufficient in supplies, an institutional continuation of the

Northern Wei and Sui military systems. Like the Sui founder, Li Yüan and his

son and successor, Li Shimin, understood the importance of pacifying both China

and the lands to the north. This was why Li Yüan took such care to settle large

numbers of his soldiers on lands near to the steppes. Li Shimin, better known

by his reign title of Tang Taizong, was particularly successful at this, using

both military and diplomatic strategies to become not only emperor of the

Chinese but Qaghan (essentially, “Emperor”) of the Turks as well.

Unlike members of the traditional ruling classes of southern

China, but like Tang Taizong, many of the leading figures of the early decades

of the Tang were very comfortable with steppe traditions such as hunting and

the relative freedom of women-a result of the intermingling of Chinese and

nomadic peoples during the period of disunion. Applying this knowledge, Taizong

took advantage of disunion among the various steppe tribes to insinuate himself

into their politics and feuds. The result was that many of the nomadic tribes

became an arm of the Tang military system. Taizong thus solved-at least for a

time-the main problem plaguing Chinese armies since the Zhou period: the lack

of horses, needed to create a credible cavalry arm. The nomads made up the bulk

of the Tang cavalry during the reign of Taizong, and they were called on at

times to assist in his campaigns for the consolidation of Tang rule within

China proper. Those few times steppe tribes refused to heed his orders, he sent

Tang armies, aided by other steppe cavalry, to bring them to heel.

Taizong was accepted due to his adaptation to steppe

traditions, especially his knowledge of steppe politics and military tactics.

Frequently, he led his soldiers in person, often when outnumbered by enemy

forces, reportedly having four horses shot out from under him during the course

of his campaigns. He was also acquainted with the steppe military tactic of the

feigned retreat, adapting this tactic successfully from its use with cavalry

forces to use with primarily infantry forces.

Later Tang emperors were unable to maintain the sort of

personal authority that was necessary to control the steppe nomads. But nomadic

internal rivalries allowed the Tang dynasty to keep its northern frontier

fairly secure for a few decades after Taizong’s death. Even after Tang control

on the frontiers weakened later in the eighth century, the dynasty could often

call on nomadic armies for assistance. But Tibetan invasions and the An Lushan

Rebellion in the mid-eighth century, coupled with ongoing transformations of

the Chinese economy and society, would finally destroy the almost symbiotic

system of nomadic cavalry alongside settled Chinese infantry.

The Tang Army

The Fubing System The Tang dynasty, especially from the time of

Tang Taizong, consciously worked to create a system whereby the dynasty was

primarily defended by citizen-soldiers. Like the Han dynasty, the Tang was

suspicious of large professional armies, believing that skilled professionals

were much harder to control or to keep loyal than an army composed of free

citizens. The Tang also believed that some skilled professionals were

necessary, especially for the expeditions the dynasty planned in both the north

and south and as a mobile strike force. As we have seen, the cavalry arm was

primarily made up of nomadic horsemen who could be both used as a buffer and

called on to assist in military expeditions. In the next section, we will

discuss the skilled professional force that was kept near the capital. In this

section, we will focus on the large forces of citizen-soldiers called the

Fubing Army.

The term Fubing has been translated in various ways, the

most common being “militia.” This is not satisfactory. Militia

usually refers to men who are soldiers only part-time or part of the year; the

rest of the time, they engage in their primary occupation. The members of the

Fubing, however, were primarily professional soldiers, members of a standing

army who spent all or nearly all of the year in military units, training or

engaging in security duties.

The confusion in meaning comes from how the Fubing were

recruited, and, sometimes, the Chinese sources from the Tang period are

themselves unclear as to what the functions of the Fubing were. Nonetheless, in

tracing the evolution of the Fubing, we learn that in the early Tang, at least

up until the end of the eighth century, it was the most effective part of the

Tang military, maintaining the security of the Tang frontier and assisting in

several of the early Tang military expeditions. The Fubing commanders were some

of the best in the whole Tang military.

Li Yüan established the capital of Tang China at Changan,

located in the Guanzhong Province. As we saw earlier, by this time, he had over

200,000 men in his command. Although more fi ghting would be necessary to

establish control over the rest of China, Li Yüan needed to ensure that the

northern frontier was secure. To that end, many of these soldiers and their

families were settled in agricultural communities. When additional soldiers were

needed for his armies, Li Yüan had these families furnish them, along with

their equipment and weapons. As these communities were expected to be

self-supporting, the Tang court was spared a large expense. When this

system-obviously extensively copied from the Sui military system-was expanded

to include all ten of the provinces under Tang Taizong, the Tang had seemingly

solved all three of the main Chinese military concerns. That is, there were

military forces on the northern frontier to protect against nomadic threats;

scattered military units were available for internal uses; and, because all

these forces were self-supporting, there was little drain on imperial finances.

When the Fubing system was established, there were 623

communities, each with 800-1200 soldiers plus their families, making a total

military force of well over 600,000. While the soldiers trained, their families

were required to work their assigned lands, much as in the Sui and the Northern

Wei earlier. But a key difference was that during the Tang dynasty, little

private landownership was allowed in China, and all land was divided up

according to a very complicated formula. This Equitable-Field system was

implemented throughout the early Tang and was the basis for the Fubing military

system. Those communities classifi ed as military were allotted a certain

amount of land, which in the early decades of the Fubing system was quite

large. In return for providing soldiers and supplying military needs, these

communities were exempted from many taxes. Officers from the Imperial Guards in

the capital were dispatched to the Fubing communities to oversee the

administration of the lands and to lead the soldiers when necessary. This was

to prevent local commanders from bonding too tightly with their men and gaining

too much independent power, though lower-ranking officers usually came from

within the ranks.

Recruitment was not by universal conscription, nor was it a

strictly hereditary duty as under previous systems such as the Sui. Instead,

roughly once every three years, officers of the Imperial Guards would circuit

the Fubing communities and recruit, choosing on the basis of wealth, physical

fitness, and number of adult males in a military household. Though the age of

recruitment varied over time, generally a man was enlisted from age 20, and he

would serve until age 60, when he could retire. Membership in the early decades

was considered an honor, and those families with wealth and influence were able

to get a higher proportion of their sons accepted. It is not clear how rigidly

the physical requirements were enforced, but recruits were supposed to be in

good health and were tested on physical strength. Those from frontier

communities were also tested on their horsemanship.

After being accepted as a Fubing soldier, the new recruit

and his family were expected to provide all of his rations, armor, and weapons.

Groups of families were required to provide horses, mules, or oxen for use by

the Fubing. This was a relatively cost-free way for the Tang to maintain a

standing army, its only expense being the allocated land.

The three main duties of the Fubing were, in order of

importance, garrison troops on the frontier, guardsmen in the capital area of

Changan, and combat troops on expeditions. Local commanders of the Fubing were

expressly forbidden to move their troops out of their camps without

authorization from the court. There were exceptions in emergencies, but a

commander who did move his men without prior approval had to notify the court

immediately. Punishment for failing to follow these rules was exile or even

death for the offending commander. Throughout the seventh century, the Fubing

acquitted itself well along the frontiers and also maintained the Tang hold

over the newly unified southern territories.

Guard duty in the capital area was considered a particularly

important function of the Fubing by the Tang court. A complicated rotation

system was devised to determine which Fubing units had guard duty and when. At

any given time, there were tens of thousands of Fubing soldiers in various

defensive positions in Changan and the immediate area. They were not the only

military forces in the capital, but they were considered a check on the Palace

Army that was supposedly the personal military force of the emperor.

Taking part in Tang military campaigns was the third duty of

the Fubing. Rarely did the Fubing campaign on their own. Most often, they went

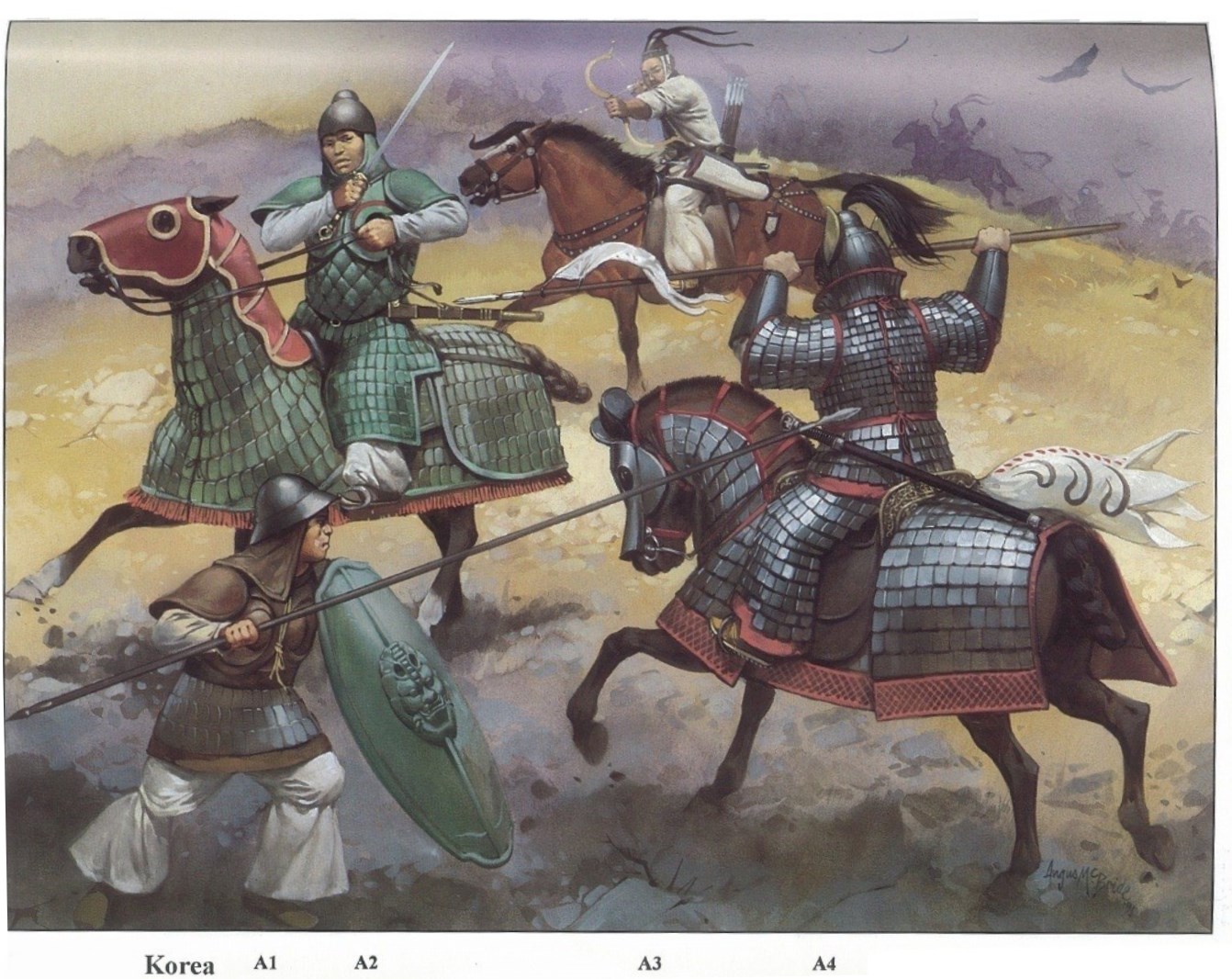

into combat with large numbers of other Tang military units. The Korean

campaigns, for example, were manned primarily by troops recruited from regions

near Korea, but the Fubing were often the backbone of the expeditionary force.

Also, an expeditionary force sent to subdue the kingdom of Nanchao (the

present-day Chinese province of Yunnan) contained a large number of Fubing

soldiers.

There is general agreement that through the 600s the Fubing

were a competent, efficient military force that remained loyal to the Tang

court. However, changes in Tang China’s economy and society in the early- to

mid-eighth century led to the decline of the Fubing. The Equitable-Field system

was without doubt the foundation of the Fubing military system, but in the

early 700s, aristocratic families, government officials, religious orders, and

others with influence were gaining effective private ownership of land. Many of

the Fubing lands passed into private hands, and many military households saw

their share of land reduced drastically. Service in the Fubing became less

prestigious, and families increasingly saw classification as a military

household as a burden and attempted various means to have their status changed

to civilian. Many families attached themselves to Buddhist temples or religious

orders as a quick way to relieve themselves of the burden of supplying the Fubing.

Many others fled to newly reclaimed lands, becoming tenant-farmers or laborers

on the lands of the wealthy in preference to service as a Fubing household,

testament to how burdensome that service had become. Reports in the 740s told

of massive desertions from the Fubing armies, at the same time that fierce

Tibetan armies were raiding the northern and northwestern frontiers. The Fubing

system was formally abolished in favor of a system of voluntary, recruited

soldiers in 749.

The Palace Army In addition to the Fubing units that were

expected to be composed of citizensoldiers, the Tang maintained a professional

force at the capital of Changan, designed as the personal army of the emperor.

This was the Palace Army, composed originally of those units used by Li Yüan in

his revolt against the Sui dynasty. Often, this army is called the

“Northern Army” because it was originally posted in a defensive

position just north of Changan, as well as in the northern sector of the city.

By Tang Taizong’s time, nearly all of the soldiers in this army were from noble

or wealthy families located in the capital region.

At its height of effectiveness in the late seventh century,

there were probably no more than 60,000 men in the Palace Army. In this early

period, it was the core of Tang military strength and even included a cavalry

element. Members of this army trained constantly together, and those who were

tall and strong and showed ability at horse-archery were admitted to the

cavalry, commanded mostly by specially recruited Turkish officers.

Other than some of the cavalry officers, most officers in

the Palace Army came from the Imperial Guards. Indeed, most of the top Fubing

officers were also Imperial Guardsmen. The Imperial Guards were recruited

exclusively from the families of nobles and former high-ranking officials, and

some have seen this as a modified version of the “hostage system”

that had been used by the Han dynasty to maintain some measure of control over

powerful families. As long as membership in the Imperial Guards was esteemed,

there was a constant flow of competent, energetic officers for both the Palace

Army and the Fubing. But by the late seventh century, the Imperial Guards- and

therefore the Palace Army-had become involved in imperial succession struggles,

and their effectiveness had diminished considerably.

The empress Wu (690-705) greatly expanded the Palace Army,

enlisting men from outside the traditional recruiting grounds. This could have

been an invigorating move that revitalized the military efficiency of the

Palace Army; but, instead, a major unit of the Palace Army was used in 705 to

depose the empress, and various other units later were frequently called on to

assist in court intrigues. During the outbreak of the An Lushan Rebellion in

755, the Palace Army simply melted away as the rebel forces approached. Only

1000 of the supposedly elite force were left to accompany the emperor as he

fled the capital.

The Decline of Tang

Military Efficiency

New Frontier Armies Constant and growing threats from a newly

unified Tibetan kingdom in the late seventh century demonstrated the increasing

feebleness of the Fubing military system. The Tang relied to a large degree on

their Uighur and Turkish nomadic allies, who by this time could no longer be

considered even remotely under the control of Tang China. The Uighurs had been

especially effective in assisting the Tang, but they did not come cheap. By the

670s, vast amounts of silk and other goods were necessary to buy Uighur

assistance. When the payments slacked, the Uighurs would strike within China to

exact payment and, since the Fubing garrisons were significantly weakened,

their raids were often successful. To lessen reliance on the hired Uighur

cavalry and protect the frontier, the Tang replaced the Fubing system with one

of long-serving volunteer frontier armies, led by imperially appointed military

governors possessing a good deal of civil as well as military authority.

For military encampments for these new troops, the Tang

constructed massive fortresses across the three provinces that bordered the

steppe frontier. The frontier fortresses were connected to and communicated

with each other and the capital by post roads and beacon towers. In some cases,

the fortresses were constructed on former Turkish territory. While the Turks

were away in battle with tribes further west, the Tang army moved in swiftly to

secure the area, constructing fortresses and denying the Turks some of their

prime pasturelands. By the 720s, there were well over 65,000 soldiers with 15,000

horses stationed in Guanzhong alone, with comparable numbers in the adjoining

two provinces.

This entailed an enormous expense, and, though the Tang was

a fairly prosperous time in China’s history, this level of outlay proved difficult

to maintain. Unlike the Fubing forces, these frontier armies were not

self-supporting, nor could they be, with many of the soldiers posted relatively

far north in lands less suited to settled agriculture. The difficulty of paying

these forces prompted dangerous political arrangements. Taxing authority was

given over to the military governors, who increasingly ruled independently of

the court.

Until 750, the system appeared to be working. Tang China

faced a series of ups and downs in terms of security along their frontiers, but

none of the problems they encountered was very serious. Trade through the Tang

possessions in Central Asia continued fairly smoothly, and the nomadic peoples

on all fronts were, if not fully pacifi ed, at least not of serious concern.

But the year 751 saw three major military disasters for the Tang. The first

occurred at the Talas River on the western frontier, where a major Chinese

force under the veteran Korean general Gao Xianzhi was decisively defeated by a

combined Arab-Turkish force. Another Chinese army, on the northeastern

frontier, led by the Turkish-Soghdian general An Lushan, was decisively

defeated by a predominantly Khitan nomadic force. Then, a major Chinese army

was defeated and wiped out in an invasion of the Nanchao kingdom in the

southwest, leaving the Sichuan area of China vulnerable to renewed Tibetan

attacks. The combination of defeats seriously destabilized the dynasty.

Transformation and Decline The Tang dynasty faced two big problems

in trying to rebuild its military forces after the disasters of the mid-700s.

First, although the large frontier armies did not fare well in combat against

foreign forces, internally, their commanders continued to accrue tremendous

independent power. The threat to central authority posed by military commanders

and the great warrior aristocracy became acute in the 800s as commanders gained

control of the civil government in their provinces and won the right to

hereditary succession to their commands. In the end, independent warlords

brought down the dynasty-a development that would significantly influence the

military policy of the succeeding Song dynasty.

Second, the increasing demographic and economic influence of

southern China in the empire as a whole had significant ramifications for the

social and military structure. The south was even more unsuitable terrain for

raising horses and maintaining cavalry traditions than the north of China. As a

result, Chinese reliance on nomadic tribes for cavalry became even greater at

the same time as the rulers of China became even more distanced from the

culturally syncretic milieu that had produced the leaders of the early Tang.

Thus, Chinese control over their nomadic allies waned, and cavalry warfare became

more and more divergent from native Chinese military traditions. This, too,

would fuel the Song reaction against great warrior aristocratic families, who

most strongly embraced those traditions.

Events reached crisis proportions because of the independent

power of military commanders. An Lushan, the most powerful Tang general and a

court favorite, rebelled in 755. After seven years of chaotic fighting, the

various rebel forces were finally defeated, but only with significant aid from

nomadic Uighur horsemen, who became a problem in turn. A succession of emperors

rebuilt a central army around the core of a loyal frontier army; this Shence

Army was led by eunuchs, reflecting an effort to solve the problem of commander

loyalty. Though temporarily successful-the Shence Army was instrumental in

putting down another rebellion by military governors in 781-the institution had

little success controlling the nomadic frontier because of its central location

in the capital. Further, its power was steadily diluted by aristocratic infl

uence, money shortages caused by the independence of the military governors,

and involvement in court politics. Increasingly enfeebled, the Tang dynasty finally

fell in 907, ushering in several decades of warfare that would accelerate the underlying

changes in China’s political, social, and military structure.