“The thrust is

the best parry”

Worried by the threatening developments the day before on

his front and flanks, Model, early on 23 July, predicted that the Russians

would strike via L’vov to the San River, thrust past Lublin to Warsaw, encircle

Second Army at Brest, advance on East Prussia across the Bialystok-Grodno line

and by way of Kaunas, and attack past the army group left flank via Shaulyay to

Memel or Riga. During the day Model’s concern, particularly for his south

flank, grew to alarm as the Russians moved north rapidly between the Vistula

and the Bug toward Siedlce, the main road junction between Warsaw and Brest. In

the late afternoon, after several of his reports had gone unanswered, Model

called to tell the Operations Branch, OKH, it was “no use sitting on one’s

hands, there could be only one decision and that was to retreat to the

Vistula-San line.” The branch chief replied that he agreed, but Guderian

wanted to set a different objective. Later the army group chief of staff talked

to Guderian, who quickly took up a proposal to create a strong tank force around

Siedlce but would not hear of giving up any of the most threatened points.

“We must take the offensive everywhere!” he demanded, “To

retreat any farther is absolutely not tolerable.”

Before daylight the next morning Guderian had completed a

directive which was issued over Hitler’s signature. Army Groups North and North

Ukraine were to halt where they were and start attacking to close the gaps.

Army Group Center was to create a solid front on the line

Kaunas-Bialystok-Brest and assemble strong forces on both its flanks. These

would strike north and south to restore contact with the neighboring army

groups. All three army groups were promised reinforcements. The directive ended

with the aphorism “The thrust is the best parry” (der Hieb ist die

beste Parade). After reading the directive Model’s chief of staff told the OKH

operations chief it would be seven days before the army groups would get any

sizable reinforcements—in that time much could happen.

During the last week in the month the Soviet armies rolled

west through the shattered German front. On 24 July First Panzer Army still

held L’vov and its front to the south, but behind the panzer army’s flank, 50

miles west of L’vov, First Tank Army, Third Guards Tank Army, and the

Cavalry-Mechanized Group Baranov had four tank and mechanized corps closing to

the San River on the stretch between Jaroslaw and Przemysl. That day Fourth

Panzer Army fell back 25 miles to a 40-mile front on the Wieprz River southeast

of Lublin; off both its flanks the Russians tore open the front for a distance

of 65 miles in the south and 55 miles in the north. Second Army had drawn its

three right flank corps back to form a horizontal V with the point at Brest.

Behind the army a Second Tank Army spearhead reached the outskirts of Siedlce

at nightfall on the 24th, and during the day Forty-seventh and Seventieth

Armies had turned in against the south flank.

To defend Siedlce, Warsaw, and the Vistula south to Pulawy,

Model, on the 24th, returned Headquarters, Ninth Army, to the front and gave it

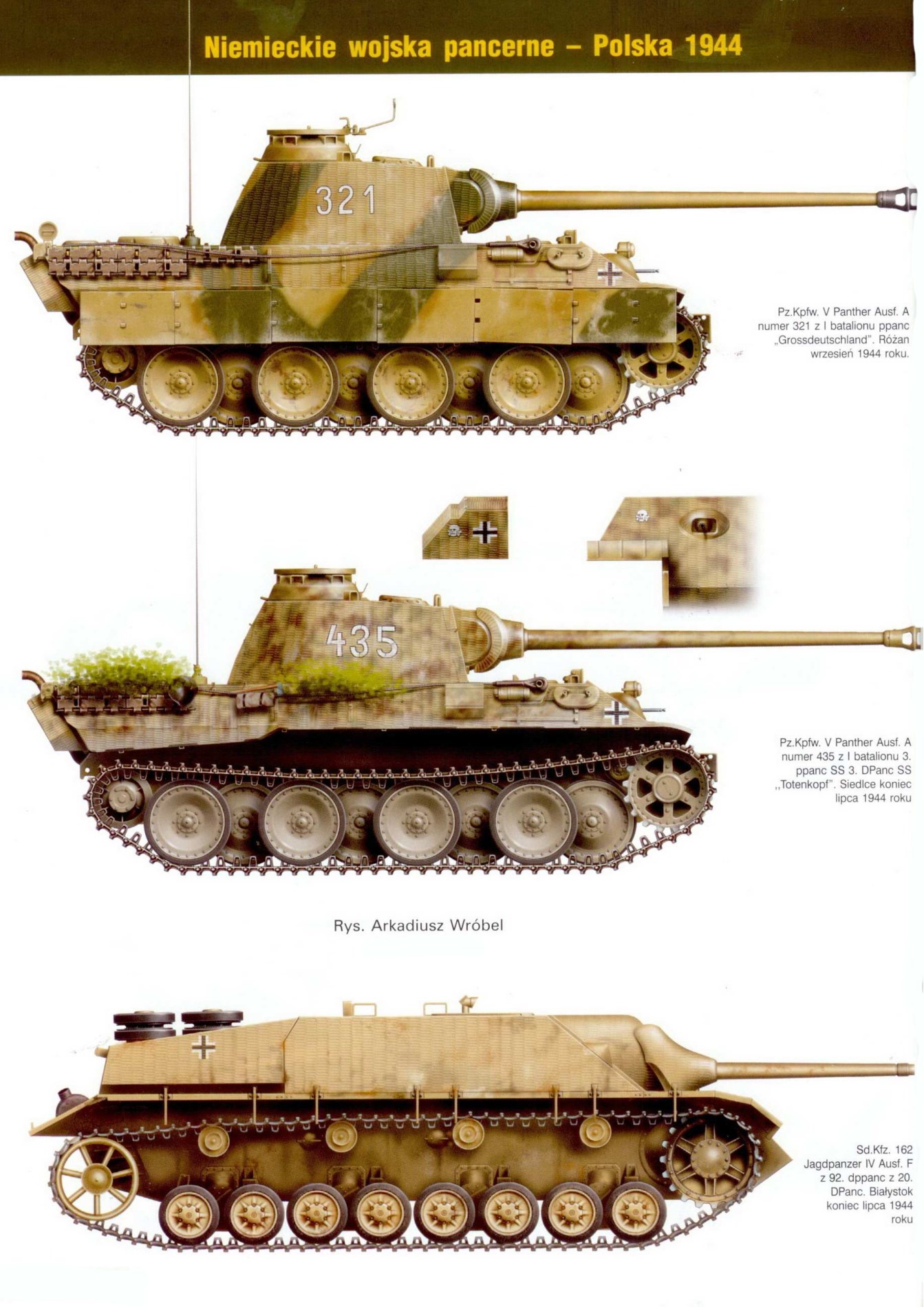

the Hermann Göring Division, the SS Totenkopf Division, and two infantry

divisions, the latter three divisions still in transit. From the long columns

coming west across the Vistula, the army began screening out what troops it

could. In Warsaw it expected an uprising any day.

The next day Fourth Tank Army crossed the San between

Jaroslaw and Przemysl. To try to stop that thrust, Army Group North Ukraine, on

orders from the OKH, took two divisions from Fourth Panzer Army and gave the

army permission to withdraw to the Vistula. In the Ninth Army sector

Rokossovskiy’s armor pierced a thin screening line around the Vistula crossings

at Deblin and Pulawy and reached the east bank of the river.

Morning air reconnaissance on the 26th reported 1,400 Soviet

trucks and tanks heading north past Deblin on the Warsaw road. At the same

time, on the Army Group Center north flank reconnaissance planes located

“endless” motorized columns moving west out of Panevezhis behind

Third Panzer Army. During the day Second Army declared it could not hold Brest

any longer, but Hitler and Guderian refused a decision until after midnight, by

which time the corps in and around the city were virtually encircled.

In two more days First Panzer Army lost L’vov and fell back

to the southwest toward the Carpathians. Fourth Panzer Army went behind the

Vistula and beat off several attempts to carry the pursuit across the river.

Ninth Army threw all the forces it could muster east of Warsaw to defend the

city, hold Siedlce, and keep open a route to the west for the divisions coming

out of Brest. South of Pulawy two Soviet platoons crossed the Vistula and

created a bridgehead; Ninth Army noted that the Russians were expert at

building on such small beginnings.

In the gap between Army Groups Center and North, Bagramyan’s

motorized columns passed through Shaulyay, turned north, covered the fifty

miles to Jelgava, and cut the last rail line to Army Group North. In a

desperate attempt to slow that advance, Third Panzer Army dispatched one panzer

division on a thrust toward Panevezhis. Hitler wanted two more divisions put

in, but they could only have come from the front on the Neman, where the army

was already losing its struggle to hold Kaunas.

The 29th brought Army Group Center fresh troubles. Nine rifle divisions and two guards tank corps hit the Third Panzer Army right flank on the Neman front south of Kaunas. Rokossovsky’s armor drove north past Warsaw, cutting the road and rail connections between the Ninth and Second Armies and setting the stage for converging attacks on Warsaw from the southeast, east, and north.

On the 30th the Third Panzer Army flank collapsed, the

Russians advanced to Mariampol, twenty miles from the East Prussian border, and

could have gone even farther had they so desired. Between Mariampol and Kaunas

the front was shattered. In Kaunas and in the World War I fortifications east

of the city two divisions were in danger of being ground to pieces as the enemy

swung in behind them from the south. Model told Reinhardt that the army group

could not grant permission to give up the city and it was useless to ask the

OKH. Reinhardt replied, “Very well, if that is how things stand, I will

save my troops”; at ten minutes after midnight he ordered the corps

holding Kaunas to retreat to the Nevayazha River ten miles to the west.

On the Warsaw approaches during the day Second Tank Army

came within seven miles of the city on the southeast and took Wolomin eight

miles to the northeast. In the city shooting erupted in numerous places. In the

San-Vistula triangle First Tank Army stabbed past Fourth Army and headed

northwest toward an open stretch of the Vistula on both sides of Baranow. Off

the tank army’s south flank the OKH gave the Headquarters, Seventeenth Army,

command of two and a half divisions to try to plug the gap between Fourth Army

and First Panzer Army.

On the last day of the month elements of a guards mechanized corps reached the Gulf of Riga west of Riga. Forty miles south of Warsaw Eighth Guards Army took a small bridgehead near Magnuszew. Between the Fourth and Seventeenth Armies, First Tank Army began taking its armor across the Vistula at Baranow. That day, too, for the first time, the offensive faltered: Bagramyan did not move to expand his handhold on the Baltic; apparently short of gasoline, the tanks attacking toward Warsaw suddenly slowed almost to a stop; a German counterattack west from Siedlce began to make progress; and General Ivan Danilovich Chernyakovsky did not take advantage of the opening between Mariampol and Kaunas.

At midnight on 31 July Hitler reviewed the total German

situation in a long, erratic, monologue delivered to Jodl and a handful of

other officers. The news from the West was also grim: there the Allies were

breaking out of the Cotentin Peninsula, and on the 31st U.S. First Army had

passed Avranches. Nevertheless, the most immediate danger, Hitler said, was in

the East, because if the fighting reached into Upper Silesia or East Prussia,

the psychological effects in Germany would be severe. As it was, the retreat was

arousing apprehension in Finland and the Balkan countries, and Turkey was on

the verge of abandoning its neutrality. What was needed was to stabilize the

front and, possibly, win a battle or two to restore German prestige.

The deeper problem, as Hitler saw it, was “this human,

this moral crisis,” in other words, the recently revealed officers’

conspiracy against him; he went on:

“In the final

analysis, what can we expect of a front . . . . if one now sees that in the

rear the most important posts were occupied by downright destructionists, not

defeatists but destructionists. One does not even know how long they have been

conspiring with the enemy or with those people over there [Seydlitz’s League of

German Officers]. In a year or two the Russians have not become that much

better; we have become worse because we have that outfit over there constantly

spreading poison by means of the General Staff, the Quartermaster General, the

Chief of Communications, and so on. If we overcome this moral crisis . . . in

my opinion we will be able to set things right in the East.”

Fifteen new grenadier divisions and ten panzer brigades

being set up, he predicted, would be enough to stabilize the Eastern Front.

Being pushed into a relatively narrow space, he thought, was not entirely bad;

it reduced the Army’s need for manpower-consuming service and support

organizations.

The Recovery

In predicting that the front could be stabilized, Hitler

came close to the mark. In fact, even his expressed wish for a victory or two

was about to be partially gratified. Model was keeping his forces in hand, and

he was gradually gaining strength. Having advanced, in some instances more than

150 miles, the Soviet armies were again getting ahead of their supplies. The

flood had reached its crest. It would do more damage; but in places it could

also be dammed and diverted.

Crosscurrents

On 1 August Third Panzer Army, not yet recovered from the

beating it had taken between Kaunas and Mariampol, shifted the right half of

its front into the East Prussia defense position. Third Belorussian Front,

following close, cut through this last line forward of German territory in

three places and took Vilkavishkis, ten miles east of the border. The general

commanding the corps in the weakened sector warned that the Russians could be

in East Prussia in another day.

The panzer army staff, set up in Schlossberg on the west

side of the border, found being in an “orderly little German city almost

incomprehensible after three years on Soviet soil.” But Reinhardt was

shaken, almost horrified, when he discovered that the Gauleiter of East

Prussia, Erich Koch, who was also civil defense commissioner for East Prussia,

had not so much as established a plan for evacuating women and children from

the areas closest to the front. The army group chief of staff said that he had

been protesting daily and had been ignored; apparently Koch was carrying out a

Führer directive.

In Warsaw on 1 August the Polish Armia Krajowa (Home Army),

under General Tadeusz Bor-Komorowski, staged an insurrection. The Poles were

trained and well-armed. They moved quickly to take over the heart of the city

and the through streets, but the key points the insurgents needed to establish

contact with the Russians, the four Vistula bridges and Praga, the suburb on

the east bank, stayed in German hands. Worse yet for the insurgents, south of

Wolomin the Hermann Göring Division, 19th Panzer Division, and SS Wiking

Division closed in behind the III Tank Corps, which after sweeping north past

Warsaw had slowed to a near stop on 31 July. In the next two or three days,

while the German divisions set about destroying III Tank Corps, Second Tank

Army shifted its effort away from Warsaw and began to concentrate on enlarging

the bridgehead at Magnuszew, thirty-five miles to the south.

Stalin was obviously not interested in helping the

insurgents achieve their objectives: a share in liberating the Polish capital

and, based on that, a claim to a stronger voice in the post-war settlement for

Premier Stanislaw Mikolajczyk’s British-and-American-supported exile

government. On 22 July the Soviet Union had established in Lublin the

hand-picked Polish Committee of National Liberation, which as one of its first

official acts came out wholeheartedly in favor of the Soviet-proposed border on

the old Curzon Line, the main point of contention between the Soviet Union and

the Mikolajczyk government. That Mikolajczyk was then in Moscow (he had arrived

on 30 July) negotiating for a free and independent Poland added urgency to the

revolt but at the same time reduced the insurgents in Soviet eyes to the status

of inconvenient political pawns.

Army Group North Ukraine on 1 August was in the second day

of a counterattack, which had originally aimed at clearing the entire

San-Vistula triangle, but which had been reduced before it started to an

attempt to cut off the First Tank Army elements that had crossed the Vistula at

Baranow. Although Seventeenth Army and Fourth Panzer Army both gained ground,

they did not slow or, for that matter, much disturb Konev’s thrust across the

Vistula. A dozen large pontoon ferries, capable of floating up to sixty tons,

were transporting troops, tanks, equipment, and supplies of Third Guards Tank

and Thirteenth Armies across the river. By the end of the day Fourth Panzer

Army had gone as far as it could. The next afternoon the army group had to call

a halt altogether. The divisions were needed west of the river where First Tank

Army, backed by Third Guards Tank Army and Thirteenth Army, had forces strong

enough to strike, if it chose, north toward Radom or southwest toward Krakow.

On the night of 3 August Model sent Hitler a cautiously

optimistic report. Army Group Center, he said, had set up a continuous front

from south of Shaulyay to the right boundary on the Vistula near Pulawy. It was

thin—on the 420 miles of front thirty-nine German divisions and brigades faced

an estimated third of the total Soviet strength—but it seemed that the time had

come when the army group could hold its own, react deliberately, and start

planning to take the initiative itself. Model proposed to take the 19th Panzer

Division and the Hermann Göring Division behind the Vistula to seal off the

Magnuszew bridgehead, to move a panzer division into the Tilsit area to support

the Army Group North flank, and to use the Grossdeutschland Division, coming

from Army Group South Ukraine, to counterattack at Vilkavishkis. He planned to

free two panzer divisions by letting Second Army and the right flank of Fourth

Army withdraw toward the Narew River. With luck, he thought, these missions

could be completed by 15 August. After that, he could assemble six panzer

divisions on the north flank and attack to regain contact with Army Group

North.

For a change, fortune half-favored the Germans. The Hermann

Göring Division and the 15th Panzer Division boxed in the Magnuszew bridgehead.

Against the promise of a replacement in a week or so, Model gave up the panzer

division he had expected to station near Tilsit. The division went to Army

Group North Ukraine where Konev, after relinquishing the left half of his front

to the reconstituted Headquarters, Fourth Ukrainian Front, under General

Polkovnik Ivan Y. Petrov, was now also pushing Fourth Tank Army into the

Baranow bridgehead. The bridgehead continued to expand like a growing boil but

not as rapidly as might have been expected considering the inequality of the

opposing forces.

In the second week of the month three grenadier divisions

and two panzer brigades arrived at Army Group Center. On 9 August the

Grossdeutschland Division attacked south of Vilkavishkis. Through their agents

the Russians were forewarned. They were ready with heavy air support and two

fresh divisions. This opposition blunted the German attack somewhat, but the

Grossdeutschland Division took Vilkavishkis, even though it could not

completely eliminate the salient north of the town before it was taken out and

sent north on 10 August.

A Corridor to Army

Group North

In the first week of August the most urgent question was

whether help could be brought to Army Group North before it collapsed completely.

On 6 August Schörner told Hitler that his front would hold until Army Group

Center had restored contact, provided “not too much time elapsed” in

the interval; his troops were exhausted, and the Russians were relentlessly

driving them back by pouring in troops, often 14-year-old boys and old men, at

every weak point on the long, thickly forested front. To Guderian he said that

if Army Group Center could not attack soon, all that was left was to retreat

south and go back to a line Riga-Shaulyay-Kaunas, and even that was becoming

more difficult every day.

On 10 August Third Baltic and Second Baltic Fronts launched

massive air and artillery-supported assaults against Eighteenth Army below

Pskov Lake and north of the Dvina. They broke through in both places on the

first day. Having no reserves worth mentioning, Schörner applied his talent for

wringing the last drop of effort out of the troops. To one of the division

commanders he sent the message: “Generalleutnant Charles de Beaulieu is to

be told that he is to restore his own and his division’s honor by a courageous

deed or I will chase him out in disgrace. Furthermore, he is to report by 2100

which commanders he has had shot or is having shot for cowardice.” From

the Commanding General, Eighteenth Army, he demanded “Draconian

intervention” and “ruthlessness to the point of brutality.”

To boost morale in Schörner’s command, the Air Force sent

the Stuka squadron commanded by Major Hans Rudel, the famous Panzerknacker

(tank cracker), who a few days before had chalked up his 300th Soviet tank

destroyed by dive bombing. Hitler sent word on the 12th that Army Group Center

would attack two days earlier than planned. From Königsberg the OKH had a

grenadier division airlifted to Eighteenth Army.

Army Group Center began the relief operation on 16 August.

Two panzer corps, neither fully assembled, jumped off west and north of

Shaulyay. Simultaneously, Third Belorussian Front threw the Fifth,

Thirty-third, and Eleventh Guards Armies against Third Panzer Army’s right

flank and retook Vilkavishkis. During the day Model received an order

appointing him to command the Western Theater. Reinhardt, the senior army

commander, took command of the army group, and Generaloberst Erhard Raus

replaced him as Commanding General, Third Panzer Army.

The next day, while the offensive on the north flank rolled ahead, Chernyakovsky’s thrust reached the East Prussian border northwest of Vilkavishkis. One platoon, wiped out before the day’s end, crossed the border and for the first time carried the war to German soil. In the next two days the Russians came perilously close to breaking into East Prussia.

On the extreme north flank of Third Panzer Army two panzer

brigades, with artillery support from the cruiser Prinz Eugen standing offshore

in the Gulf of Riga, on the 10th took Tukums and made contact with Army Group

North. On orders from the OKH, the brigades were immediately put aboard trains

in Riga and dispatched to the front below Lake Peipus. The next day Third

Panzer Army took a firmer foothold along the coast from Tukums east and

dispatched a truck column with supplies for Army Group North. On the East

Prussian border the army’s front was weak and beginning to waver, but the

Russians were by then concentrating entirely on the north and did not make the

bid to enter German territory. Reinhardt told Guderian during the day that to

expand the corridor and get control of the railroad to Army Group North through

Jelgava would take too long. He recommended evacuating Army Group North.

Guderian replied that he himself agreed but that Hitler refused on political

grounds. The offensive continued through 27 August, when Hitler ordered a

panzer division transferred to Army Group North.

At the end, the contact with Army Group North was still

restricted to an 18-mile-wide coastal corridor. For the time being that was

enough. On the last day of the month the Second and Third Baltic Fronts

suddenly went over to the defensive.

The Battle Subsides

Throughout the zones of Army Groups Center and North Ukraine, the Soviet offensive, as the month ended, trailed off into random swirls and eddies. After taking Sandomierz on 18 August First Ukrainian Front gradually shifted to the defensive even though it had four full armies, three of them tank armies, jammed into its Vistula bridgehead. North of Warsaw First Belorussian Front had harried Second Army mercilessly as it withdrew toward the Narew, and in the first week of September, when the army went behind the river, took sizable bridgeheads at Serock and Rozan. But for more than two weeks Rokossovsky evinced no interest in the bridgehead around Warsaw, which Ninth Army was left holding after Second Army withdrew.

In Warsaw at the turn of the month the uprising seemed to be

nearing its end. One reason why the insurgents had held out as long as they did

was that the Germans had been unable and unwilling to employ regular troops in

the house-to-house fighting. They had brought up various remote-controlled

demolition vehicles, rocket projectors, and artillery—including a 24-inch

howitzer—and had turned the operations against the insurgents over to General

von dem Bach-Zelewski and SS-Gruppenführer Heinz Reinefarth. The units engaged

were mostly SS and police and included such oddments as the Kaminski Brigade

and the Dirlewanger Brigade. As a consequence, the fighting was carried on at

an unprecedented level of viciousness without commensurate tactical results.

On 2 September Polish resistance in the city center

collapsed and 50,000 civilians passed through the German lines. On the 9th

Bor-Komorowski sent out two officer parliamentaries, and the Germans offered

prisoner of war treatment for the members of the Armia Krajowa. The next day,

in a lukewarm effort to keep the uprising alive, the Soviet Forty-seventh Army

attacked the Warsaw bridgehead, and the Poles did not reply to the German

offer. Under the attack, the 73d Infantry Division, a hastily rebuilt Crimea

division, collapsed and in another two days Ninth Army had to give up the

bridgehead, evacuate Praga, and destroy the Vistula bridges. The success

apparently was bigger than the Stavka had wanted; on the 14th, even though 100

U.S. 4-motored bombers flew a support mission for the insurgents, the fighting

subsided. Until 10 September the Soviet Government had refused to open its

airfields to American planes flying supplies to the insurgents. On 18 September

American planes flew a shuttle mission, but the areas under insurgent control

were by then too small for accurate drops and a second planned mission had to

be canceled.

During the night of 16-17 September Polish First Army, its

Soviet support limited to artillery fire from the east bank, staged crossings

into Warsaw. The Soviet account claims that half a dozen battalions of a

planned three-division force were put across. The German estimates put the

strength at no more than a few companies, and Ninth Army observed that the

whole operation became dormant on the second day. The Poles who had crossed

were evacuated on 23 September. On the 26th Bor-Komorowski sent parliamentaries

a second time, and on 2 October his representatives signed the capitulation.

The psychological reverberations of the summer’s disasters

continued after the battles died down. In September Reinhardt wrote Guderian

that rumors in Germany concerning Busch’s alleged disgrace, demotion, suicide,

and even desertion were undermining the nation’s confidence in Army Group

Center. He asked that Busch be given some sort of public token of the Führer’s

continuing esteem. In the first week of October, Busch was permitted to give an

address at the funeral of Hitler’s chief adjutant, Schmundt, who had died of

wounds he received on 20 July. If that restored public confidence, it was

certainly no mark of Hitler’s renewed faith either in Busch or in the generals

as a class. He had already placed Busch on the select list of generals who were

not to be considered for future assignments as army or army group commanders.

After most of the eighteen generals captured by the Russians during the retreat

joined the Soviet-sponsored League of German Officers, Hitler also decreed that

henceforth none of the higher decorations were to be awarded to Army Group

Center officers.

Where Hitler saw treason in high places, others saw more

widespread, more virulent, more disabling maladies: the fear of being encircled

and captured and the fear of being wounded and abandoned. The German soldier

was being pursued by the specters of Stalingrad, Cherkassy, and the Crimea. Once,

he could not even imagine the ultimate disaster—now he expected it.