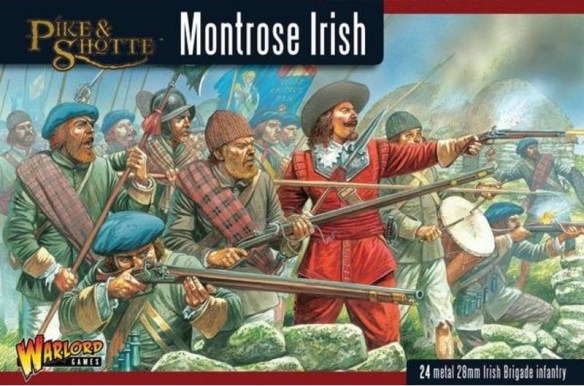

Warlord Games English

Civil Wars 1642-1652 Montrose Irish.

Catastrophe came about in 1637. King Charles I’s

determination to enforce uniformity on his churches led him to strengthen the

episcopal element in the kirk. At his much-delayed coronation in Scotland in

1633 he insisted that the Scottish bishops ape the English bishops he had

brought with him. Moreover, the Englishmen were given precedence. To follow

through this instruction in superiority, the king had his Scottish bishops

draft a liturgy, a prayer book modelled on the alien English Book of Common

Prayer. On 23 July 1637, this book was ready and was to be read from pulpits

across Scotland. At St Giles, Edinburgh, the congregation was furious—to them

this was a foreign doctrine at best, it was English at worst, and appeared to

be popish. Folding stools were hurled at the dean. Crowds outside hammered on

the doors. Across Scotland, ministers were attacked and churches stormed by

angry men and women.

Charles’s response was to treat this as an unwarranted

rebellion. Even his loyal minister, the earl of Traquair, tried to convince him

that the prayer book was a mistake, but to little avail. The Scottish council

was packed with Charles’s appointees, men with little personal authority or

experience of government, there because Charles expected their elevation to

power would ensure loyalty. As a result they had little sway with the wider

political world and less with the Scottish people. Even if inexperienced in

executive government, many had been wise enough to stay away from St Giles that

Sunday, to avoid trouble and being associated with the prayer book.

As riots occurred across Scotland, members of the Council

discussed the matter with leading opponents of the prayer book. Charles’s

refusal to discuss the matter in any meaningful way drove opponents to present

him with a Supplication and Complaint in October 1637, which put the blame on

the Scottish bishops. Charles reacted by threatening to arrest the supplicants,

and hoped to end criticism by claiming direct responsibility for the prayer

book; he believed that they would shy away from attacking the monarch. Instead,

by February 1638, a National Covenant had been drafted. This Covenant was a

reference to the 1581 Confession of Faith, which bound Scotsmen and women and

James VI together in defence of the kirk. The Covenant went further, asserting

that the religious changes imposed by James VI and Charles I were illegal

because they contravened the basis of the kirk. The National Covenant was first

signed at Edinburgh and then circulated throughout Scotland for men and women

to sign at their own church doors.

The Covenanters demanded a General Assembly and Charles

acceded, expecting his agents to be able to influence the choice of

representatives. He even ordered that the General Assembly should meet at

Glasgow, that he thought would circumvent opposition. Charles was hopelessly

out of touch and his agents were not in control. The General Assembly, which

met in November 1638, rejected the prayer book and abolished the office of

bishop. The king’s commissioner, the marquis of Hamilton, Traquair’s

replacement, failed to influence the assembly, and when he attempted to end the

session by storming out he ran into a locked door. Even after Hamilton had

managed to leave, the debates continued. Charles’s reaction to his loss of

control and influence was to prepare for war against his rebellious subjects.

By May 1639 an English and Welsh army gathered at the

border. Elaborate plans for amphibious landings on the Scottish coast were

drawn up and Hamilton prepared a fleet. In Ireland, where there was support for

the Covenanters amongst the Presbyterian ministers in Ulster, Lord Deputy

Wentworth imposed a series of oaths aimed at forcing Scots settlers to abjure

the Covenant. At the same time, the marquis of Antrim, chief of the Clan

MacDonald (known as MacDonnell in Ireland), proposed to take advantage of the

situation. He offered to raise a clan army to invade western Scotland where his

lost ancestral estates were situated and controlled by the Campbells. The

Campbells, although led by the marquis of Argyll, a supporter of the king, were

also associated with the Covenant through Argyll’s heir, Lord Lorne. Wentworth

suspected Antrim’s motive and rejected the plan, preparing an Irish army

instead, with Protestant officers and Catholic soldiers.

The first Bishop’s War in 1639 was short. The amphibious

landings were abandoned. Attempts to land at Aberdeen were called off when the

earl of Montrose and a Covenanter Army captured the town. At the eastern border

on 4 June, a section of the king’s army was defeated in a skirmish near Kelso.

This became something of a rout, and in its wake the Covenanters put forwards

proposals for discussions. That summer a truce, the Pacification of Berwick,

was negotiated, but all the while Charles I planned for war.

A new General Assembly of the kirk met in August and

confirmed its predecessor’s work. Later that same month the Estates also

assembled, and they too confirmed the actions of the General Assembly. The

Estates had been effectively controlled by Covenanters who had minimised the

role of the king in influencing the selections of members, and steps were taken

towards further controlling the business of the sessions. By the beginning of

1640, both the king and the Covenanters were preparing for renewed war.

Charles sought to improve the financial support for his

government and war effort. He planned a two-pronged approach. Wentworth

summoned a Parliament in Dublin, that he expected to manipulate into voting

four subsidies for the king. In April a Parliament would meet at Westminster

and was expected to follow suit. In March 1640 the Dublin Parliament met and

all went according to plan, but the Westminster Parliament refused to discuss

finance unless a series of grievances was addressed. The grievances were bound

up with the collection of taxation in the 1630s, religious issues, and the way

in that the 1629 Parliament had been closed. When he failed to influence the

Parliament at all, Charles dissolved it on 5 May.

Plans for war went forward, but opposition to the king had

developed in the wake of the Parliament. Soldiers mustered for the army went on

the rampage, destroying altar rails and religious images, and people across the

country began to refuse to pay taxation. Support for the Scots was to be found

across England, where people who objected to the religious reforms of

Archbishop Laud refused to pay for them to be imposed in Scotland. In Ireland,

many Scots in Ulster refused Wentworth’s oaths and left the country, leaving

tracts of countryside untilled.

The war in the summer of 1640 saw the defeat of the king’s

army at the Battle of Newburn and the occupation of northern England by the

Covenanter Army. This time peace negotiations were conducted on the Scots’

terms. They demanded freedom for the kirk, but also wanted a Parliament at

Westminster to confirm the terms. This gelled with calls within England and

Wales for a new Parliament. With an army in occupation for that he was to

provide pay, the king had no option but to accede. Parliament met on 3 November

and the king’s few supporters were overwhelmed.

Three Parliaments now worked in opposition to the king. The

Dublin Parliament had met in the summer and began to unravel the financial

arrangements it had put in place in March. It then went on to question the

relationship between itself and the lord deputy and even questioned its

subordination to the Privy Council in London. Moreover, Irish and Scots

politicians presented evidence about Wentworth’s government of Ireland and his

planned invasion of Scotland. This was taken up by Westminster and in November

Wentworth, now known as the earl of Strafford, was impeached and imprisoned

along with Archbishop Laud.

As the Dublin Parliament began to deconstruct the government

in Ireland, the Estates began to reduce the power of the king in Scottish

government. The Westminster Parliament began to take apart the machinery of

government that had sustained the Personal Rule. As well as impeaching

Strafford and Laud, Parliament aimed its ire at ministers Lord Finch and

Francis Windebank, who both fled to France to escape. Ship Money was abolished

and forest fines were banned. Two acts prevented another period of Personal

Rule: One established that there should be Parliaments at least every three

years; the other made it impossible for Parliament to be dissolved without its

own consent. In May 1641, against the background of a plot hatched amongst some

of the king’s army officers, Strafford was executed. This effectively settled

the issues raised by the Personal Rule, but Parliament presented the king with

Ten Propositions demanding a further role in government by having the right to

nominate ministers and to have a say in foreign policy.

The king went to Scotland in the summer months of 1641 to

ratify the Treaty of London, which had ended the war, and also to ratify the

acts passed in the Estates, which diminished his role in Scottish government.

The Estates had passed a series of measures that had been the inspiration for

the Westminster Parliament’s work during the spring. Charles also harboured

hopes of nurturing a royalist party in Scotland that could overthrow the

Covenanter government. The earl of Montrose, the Covenanter general, had become

disillusioned with the Covenanter cause and had questioned the ambitions of the

earl of Argyll (formerly Lord Lorne). By the time Charles went to Edinburgh,

however, Montrose was imprisoned. An attempted coup d’état, known as the

Incident, was exposed and Charles became implicated in it. With his attempts to

overturn the Covenanter government in tatters, the king returned to London.

Within days of his arrival news broke of a rebellion in Ireland.

The Irish Rebellion

In the wake of the successes at Edinburgh and Westminster,

Catholic Irish and long-established English settler families began to press for

similar changes at home. Autonomy for the Dublin Parliament was one aim, but

others related to religious issues and the tenure rights of the Catholic

population. Rights to practice their religion openly was a major demand and the

king had tentatively suggested that it might be possible. The Catholic

population too had insecure tenure on their estates having never been granted firm

property rights because of their religion. These two issues were bound together

and known as the Graces.

Given the king’s powerlessness, the Irish felt able to press

their cause. Although the Scots had secured the safety of the kirk, however,

and the Welsh and English had freed themselves from Laud’s reforms, religious

rights for Catholics were not acceptable to the Protestant Parliaments in

Edinburgh and Westminster. Frustrated groups began to discuss the possibility

of a rising in Ireland, and exiled Irishmen became involved in these

discussions. By October the discussions had crystallised into a plan to seize

strongholds throughout Ulster and Dublin Castle.

On 22 October rebellion broke out, but although the forts in

Ulster were captured by Sir Phelim O’Neill and others, Dublin remained in

government hands. By November, rebellion had spread throughout Ireland and the

Old English settlers had joined with the Catholic Irish rebels. The government

forces managed to hold onto pockets around the Irish coast, but supplies and

reinforcements were necessary if there was any possibility of remaining there.

In Edinburgh and Westminster the governments began to discuss military and

financial plans for reconquering Ireland. Whilst King Charles outwardly

discussed these issues with the Westminster Parliament, he also plotted to

seize prominent leaders. Charles was assured that there was now a significant

group of M.P.s who supported him rather than his opponents.

In late November, after heated debate, Parliament had passed

the Grand Remonstrance. This was a sort of petition that had set out the evils

of the 1630s and the remedies that had been applied; finally, the remonstrance

proposed further reforms. No sooner was this passed by the Commons than it was

published. This broadcasting of Parliament’s position was disliked by many

M.P.s. Christmastide 1641 was a period of riots in London and Westminster by

mobs supporting the aims of the Grand Remonstrance, and in particular the

removal of the bishops from the House of Lords in a move similar to the

exclusion of bishops from Scottish government. On 5 January Charles marched

into Westminster to arrest five leading M.P.s and Lord Mandeville. This coup

d’état, like that in Scotland the previous October, failed (the proposed victims

had fled), and it provoked continued rioting that in turn drove the king and

his family out of the capital.

Over the next months Charles and Parliament grew further

estranged, agreeing only on the need to fund the war against the Irish rebels.

The raising of an army to fight in Ireland drove the final wedge between the

king and Parliament, however. It was felt that the king, implicated in an army

plot and two coup d’états, could not be trusted if given the military command.

He suggested he would have to go to Ireland, especially as the rebels there

claimed to have the king’s warrant for their rebellion. With the Militia

Ordinance, Parliament took away the king’s military powers in March. In April

the king responded by trying to seize the arsenal deposited at Hull during the

Bishop’s War. He was denied entry into the city. In May Charles began the

recreation of obsolete county-based commissions of array to regain control of

the Trained Bands. Throughout the summer of 1642 both he and Parliament battled

to raise armies, each hoping to overawe the other.

In Ireland the war had taken two turns of fortune. Money and

troops had begun arriving in the spring. The marquis of Ormond took command of

the English forces and began to make inroads into rebel territory in Leinster

province. In eastern Ulster a Scottish army landed and took control of the

region in May. As summer drew on, however, attention in England had turned

inwards and the supply of resources to Ireland dried up as king and Parliament

commandeered the money for their own use. War broke out in England and Wales in

August.

Wars and Civil Wars,

1641–1653

War raged in the four nations for the next 11 years: In

Ireland there was a constant state of war; in the other three nations war was

more sporadic. Each war impinged on the others and all were closely related to

the needs of Charles I, who sought to offset failure in one nation with success

and resources from at least one of the others.

In England and Wales, the war that broke out in August 1642

began as both sides, royalists and parliamentarians, assembled field armies,

first, to try and overawe their enemy, and then, second, to inflict military

defeat in one cataclysmic battle. Neither scenario was to be enacted. By

October the king had moved from his initial musters in the North Midlands

towards London, whilst Parliament’s commander in chief, the earl of Essex,

moved westwards from the East Midlands to stop him. Scouting techniques were so

underdeveloped that the king got between the earl and London, and then the two

armies bumped into each other whilst searching for quarters. On 23 October

1643, the first major battle of the war in England took place at Edgehill.

Partly due to the inexperience within the two armies, the battle was drawn and

the war had to take on a new complexion.

After the king failed to press his attack on London in

mid-November, both sides now began a fight for territory and the resources to

maintain a nationwide war. The winter was spent in regional battles as local

commanders began to seize castles and towns in that to establish garrisons. By

the spring, the king controlled much of the south-west and north-east of

England and had a significant presence in both the North and South Midlands.

The royalists also held onto the vast majority of Wales. Parliament controlled

all major ports, the south-east and the Lancashire and Cheshire area, as well

as significant Midland areas of England, and a good proportion of Pembrokeshire

in Wales. The king believed himself to be in a strong position within the

country and as such did not take the opportunity to negotiate the end of the

war, which arose in spring 1643.

Attempts to dislodge the royalists from their strongholds in

the north, the south-west, and the South Midlands failed in the summer of 1643.

In the south-west, parliamentarian general Sir William Waller, who had met with

great success at the end of 1642, was defeated at Rowton Down in July. The earl

of Essex’s attempt to capture Oxford was curtailed in June, and that same month

the earl of Newcastle defeated the Yorkshire parliamentarians Lord Fairfax and

his son, Sir Thomas, and bottled them up in Hull. Both Parliament and the king

sought outside help at this point. At first, Scotland remained aloof from the

conflict in England and Wales. The Covenanters had offered to act as mediator

but the king had rejected their approach. The leading parliamentarian, John

Pym, had exploited the Scots’ fear of the Catholic forces in Ireland. He

suggested that the king was negotiating with the Irish, and that there might be

Irish landings on the Scottish coast as a result of such discussions. He also

hinted that if the king, who appeared to have the upper hand in England and

Wales, were to win, then he might turn on Scotland.

The Development of

the Wars

In Ireland, stalemate had developed after the funding from

across the Irish sea had dried up. The English and Scots forces held

significant areas of territory in Ulster (in Down and Antrim), around Dublin in

Leinster, and around Cork and Youghal in Munster. There were also a few

garrisons in Connacht held by the English. The Irish meanwhile had unified

their forces and their administration. Provincial armies had been created from

the disparate forces and generals appointed. A government was formed with an

executive, the Supreme Council, and a legislative, the General Assembly, which

consisted of elected representatives of the shires and boroughs. Each county

had a council of its own that sent representatives to provincial assemblies.

Despite this organisation, resources were few and the Catholic Confederation of

Kilkenny was unable to defeat the English or Scottish garrisons and armies.

Negotiations with the English began in 1643, with the aim of

getting royal recognition for the Catholic religion and for the property rights

of the Catholic peoples. The king’s representative, the earl of Ormond, was

unwilling to make major concessions, but by September at least a cease-fire had

been arranged. This Cessation allowed for the return home of the English forces

sent to Ireland in 1642, and these men were co-opted as royalist forces. This

in turn enabled Pym to show the Scots that he had been right about the

suspected negotiations, and the Scots became convinced of the need to join the

Westminster Parliament against the king. In 16 January 1644 the Army of the

Solemn League and Covenant, named after the treaty between Edinburgh and

Westminster, invaded north-east England. The English and Welsh people under the

control of Parliament would fund the invading army and there would be

consideration given to the creation of a Presbyterian church in England and

Wales.

Even before the Scots crossed the border, the war had taken

a different complexion. In September three royalist armies were weakened by

fruitless attempts to capture the prominent parliamentarian strongholds of

Hull, Gloucester, and Plymouth. Failure to capture any of them had wasted

resources and reduced the numbers of effective soldiers through disease and

injury. It took time to assemble the forces necessary to hold back the Scots,

and in the end it was fruitless—defeat at the Battle of Selby on 11 April led

to the collapse of the royalist hold on the north. The marquis of Newcastle and

his once powerful army became bottled up in York. Royalist attempts to encroach

on south-east England came to an end in the spring. Yet Parliament’s attempt to

capture Oxford again failed and a series of campaigns followed in that both Sir

William Waller and the earl of Essex were defeated by the king. Waller’s army

had been caught in Oxfordshire and destroyed. Essex had marched off into

royalist territory in the far west only to be trapped and defeated at Lostwithiel

in Cornwall at the beginning of September. On 2 July, the Northern Army and a

rescue force led to its aid by Prince Rupert were defeated at Marston moor near

York. With this defeat the royalists lost control of the north.

The king’s victories in the south, and the failure of three

combined parliamentarian armies to defeat him in the fall, temporarily offset

the loss of the north. It also led to a false confidence that led some

royalists to ridicule Parliament’s reorganisation of its war effort and the

creation of one field army from the three assembled in the autumn. This New

Model Army was created in early 1645, and in June it defeated the king at

Naseby and then set about conquering the south-west. Together, it and the

Northern Association Army won the war during the summer of 1645. During the

ensuing autumn and winter the New Model and local forces ended royalist

resistance in the south of England, whilst the Northern Association forces and

the Scots cleared the north and North Midlands of major royalist strongholds.

In Wales, Welsh parliamentarians cleared the south of the country whilst

Lancashire and Cheshire parliamentarians captured central and northern royalist

strongholds.

Fighting had broken out in Scotland during 1644. Alasdair

MacColla had led a force of Irish and Highland troops from Ireland to the

Western Isles in July 1644. The Catholic Confederation hoped that this force

would oblige the Scots to withdraw forces from Ulster; the marquis of Ormond,

who lent support to the expedition, hoped that the Scots would withdraw forces

from England. MacColla, who was of the MacDonald clan, probably hoped for both,

but also had an eye for regaining clan land lost to the Campbells. In August

1644 MacColla was joined by the earl of Montrose, by now a fully fledged

royalist. Montrose had a commission to raise the loyal Scots against the

Covenanter government. Together, the two commanders embarked on a campaign that

over the next year saw them defeat all the home armies the Edinburgh government

sent against them. At Kilsyth, on 15 August 1645, Montrose defeated the last of

these armies and Scotland appeared to be his to command. He summoned the

Estates to Glasgow and began to receive tributes from politicians. Ironically,

it was to be one of the early aims of the war that was to defeat Montrose. A

section of the Army of the Solemn League and Covenant did leave England. On 13

September David Leslie and a section of the Scots Horse caught Montrose’s men

at Philliphaugh and destroyed them. The month-old royalist domination of

Scotland was over: But guerrilla warfare was to continue in the country until

1647.

In Ireland, the king had sought a treaty not because he was

able to accept any of the Confederation’s demands, but because he needed their

military help. Ormond, part of the Protestant group that hitherto controlled

Ireland’s political world, was unwilling personally to accept the freedom

Catholics wanted for their faith. Charles sought to circumvent him by sending

the earl of Glamorgan, a Welsh Catholic, to negotiate secretly with the

Confederation. Glamorgan’s terms were more acceptable at Kilkenny, but a papal

representative, Giovanni Battista Rinuccini, arrived just before the terms were

agreed. He was wary about the secret nature of the discussions and urged

holding out for public acknowledgement. Before he could renegotiate the treaty

personally with Glamorgan, a copy of the secret treaty fell into enemy hands.

Upon the Westminster Parliament’s horrified publication of the terms, Charles I

repudiated them and Ormond arrested Glamorgan.