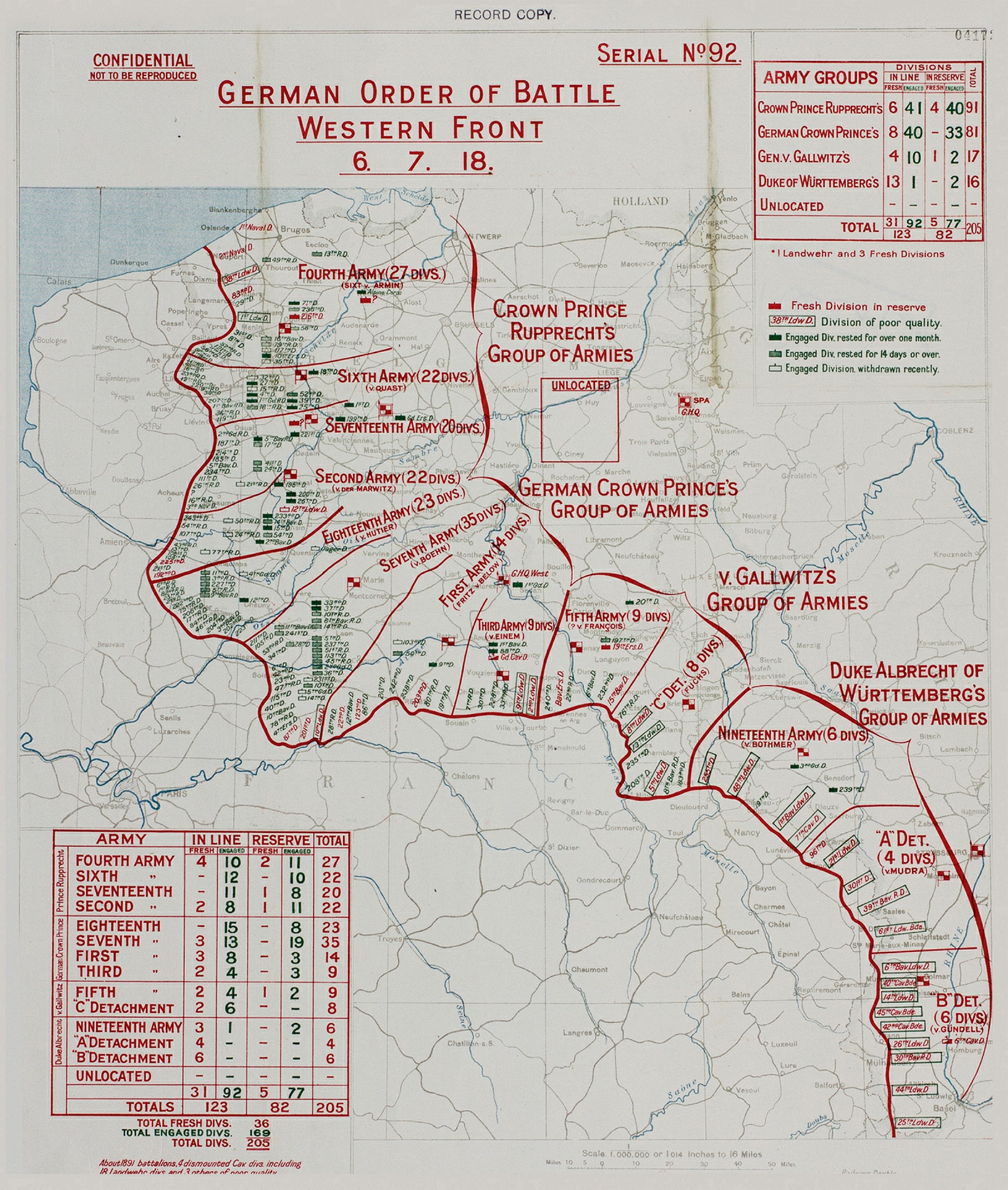

German Order of Battle, Western Front, 6.7.18, showing front line and German formations in red, Divisions in green; Divisions of poor quality in red outlined in green. The situation at the turning point of the war, as the Allied counter-offensives were beginning. Scale of original: 1:1 million.

German Order of Battle, Western Front, 11.11.18. 11.00, at the moment

of the Armistice. Scale: 1:1 million.

Battle of

Château-Thierry

French counter-attacks developed rapidly. On 18 July, the

Battle of Château-Thierry opened when the French Tenth and Sixth Armies and

American infantry were launched out of the Villers-Cotterêts Forest on a

twenty-five-mile front between Fontenoy and Château-Thierry. Their objective

was to hack into the flank of the Marne salient, and they were supported by

predicted artillery fire and 750 Renault light tanks and protected by smoke.

The Germans were forced to withdraw, and by 7 August had pulled out of the

salient, back to the river Aisne. The Allies were now strengthened in numbers

and morale by the infusion of American blood. German morale was correspondingly

lowered.

Ludendorff cancelled his intended Flanders operation, and

German soldiers, and those of their allies, were only too aware that the war

was now lost. The French were now exhausted, and most of their tanks were

destroyed, damaged or unserviceable. So Foch insisted that the task of carrying

out the next blow should fall to the British, who had recovered from their

setbacks earlier in the year and were benefiting from a massive increase in

their war production.

Battle of Hamel

On the British sector of the front, counter-offensives were

in any case being organized. On 4 July the Australians, supported by an

American infantry company, captured Hamel and Vaire Wood, east of Amiens, in an

imaginative and spirited set-piece attack involving the cooperation of predicted

artillery fire, infantry, tanks and air support.

To minimize casualties, Monash, the Australian Corps

Commander, insisted that his men should be well covered by the artillery. There

was a massive concentration of British and French batteries for this small

operation, amounting to about 600 guns and howitzers, with an emphasis on

counter-battery fire as well as bombardments in the days before the attack. For

the attack itself, surprise was achieved by the barrage opening with a crash.

This successful little attack became the model for a much larger offensive, the

Battle of Amiens. This in turn opened a series of Allied offensives, in which

the British, French and Americans all played a major part, known as the Battles

of the Hundred Days. This succession of offensives only ended with the

Armistice on 11 November.

Battles of Amiens and

Montdidier

Benefitting from the experience of the Hamel attack, the

Amiens offensive, launched on 8 August on a fourteen-mile front, was made by

Rawlinson’s Fourth Army, and spearheaded by the Canadian Corps. The aim was to

disengage Amiens, which until now was within the range of German guns, and to

free the Paris-Amiens railway. A deception plan was put into operation,

involving a Canadian wireless station, two casualty clearing stations and two

infantry battallions, to make it appear that the Canadian Corps was now in the

Kemmel area in Flanders. The operations on the French sector of the attack

frontage were known as the Battle of Montdidier.

Rawlinson’s Fourth Army pushed forward rapidly on a

nine-mile front, supported by the French on the right, and then the Canadians

and Australians, with the British 3rd Corps on the left. They were under

accurate predicted bombardment and creeping barrage fired by over 2,000 guns

and howitzers, and supported by 456 tanks, including many of the new Mark V

models. Following the precedent set by the Germans in March, all supports and

reserves began to move forward simultaneously at zero. The artillery had done

very well at counter-battery work, aided in particular by the sound-rangers who

could locate moving German batteries in haze and mist, unlike the

flash-spotters and the air force.

British offensive tactics, after the slogging of 1915–18,

were now more mobile and efficient. An advance of eight miles was made on the

first day, but many tanks, still slow and vulnerable to mechanical breakdown,

were lost to direct artillery fire. On the second day of the battle, the

British only had 145 tanks still ready for action. Armoured cars and relatively

fast Whippet tanks exploited in the rear areas, and cavalry helped to gain and

hold some positions until the infantry arrived.

German resistance stiffened, the attack soon lost impetus,

and there were no new reserves to feed the battle. But a new attack doctrine

had by now evolved. As soon as one attack lost momentum, artillery and reserves

were switched to another front and the blow repeated. Predicted fire, based on

accurate survey and mapping, maintained the element of surprise, keeping the

Germans off-balance. Wherever possible, tanks were also used to strengthen the

attack. Rawlinson’s Army captured 400 guns and inflicted 27,000 casualties on

the Germans, including 12,000 prisoners, for the loss of 9,000 men.

Battles of Albert,

Bapaume and the Drocourt–Quéant Line

Following the Amiens operations, which lasted until 12

August, the weight of the British offensive was switched, at Haig’s insistence,

to the northern sector of the Somme battlefield. Foch’s preference had been for

a continuation of the Amiens battle. The Battles of Albert and Bapaume, from

21–31 August, turned the flank of the German position on the Somme and forced

the Germans to pull back to the east bank. This series of blows continued when

the new German position was then turned from the north from 26 August to 3

September in the Battles of Arras and the Drocourt–Quéant Line. That position

being ruptured in an attack in which the Canadians and Americans took a major

role, the Germans were forced to fall back to the outer defences of the

Hindenburg Line. As the direct result of these battles, the Lys Salient further

north was evacuated by the Germans, and the British captured Lens, and

recaptured Merville, Bailleul and Mount Kemmel, and freed Hazebrouck and its

vital railway junctions, which had been under German artillery bombardment.

Battle of St Mihiel

It had always been the aim of General Pershing, the

Commander-in-Chief of the American Expeditionary Force, to concentrate American

forces in a field army under his command, rather than see them scattered

piecemeal to reinforce other Allied armies. At St Mihiel, and then more

particularly in the Meuse–Argonne battle, he achieved this. Between 12–16

September the Americans, led by Pershing, with a French corps and 267 light

tanks also under his command, fought the Battle of St Mihiel to eliminate the

German-held St Mihiel Salient, south of Verdun. Pershing planned to break

through the German lines and capture the fortress of Metz, and as his attack

caught the enemy withdrawing from the Salient, with their artillery also

pulling back and most batteries therefore out of action, it proved more

successful than expected. In a day and a half Pershing’s army, at the cost of

7,000 casualties, captured 15,000 prisoners and 450 guns.

While the success of the American attack impressed the

French and British, the operations demonstrated the difficulty of supplying

large armies in a war of movement. The attack ground to a halt as artillery and

ration trucks bogged down on the muddy roads. The US air service played a

significant part in this battle, although American fliers had been serving with

the Escadrille Lafayette since 1916. The intended attack on Metz did not in the

end take place, as the Germans took up a strong rear position and the Americans

turned their efforts further north, to the Verdun and Argonne Forest regions.

Battle of Epéhy and

the Meuse–Argonne Offensive

In the Battle of Epéhy on 18 and 19 September, British

forces broke through the outer Hindenburg defences and established jumping-off

positions for the attack on the main Hindenburg position. Foch’s grand

offensive now gathered pace along the whole Allied front. On 26 September,

Pershing’s American First and Gouraud’s French Fourth Armies began the Meuse–Argonne

offensive, on the front from Verdun to the Argonne Forest, with Pershing’s

right flank on the river Meuse and the French attacking on his left. Twenty-two

French and fifteen American divisions were involved. This, the largest American

operation of the war, lasted from 26 September to the Armistice on 11 November.

In the difficult Argonne Forest terrain of tangled woods, gullies and ridges,

it was almost impossible for tanks to operate, and the Americans found

themselves engaging in a bloody slog through a succession of strongly held

German positions.

Breaking the

Hindenburg Line

In their operations from 8 August to 26 September (the eve

of the great attack on the main Hindenburg Position), the BEF suffered 190,000

casualties. Between 26–29 September, one Belgian, five British, and two French

armies attacked the Hindenburg Line and German positions extending north to

beyond Ypres. Attacks were made by fifty British and twelve Belgian divisions,

as well as the French and Americans further south. On the whole of the Western

Front, 217 Allied divisions faced 197 German.

The attack on the Hindenburg Position, whose defences were

up to three miles in depth and included the St Quentin Canal which made a

superb anti-tank ditch, was made in the Battles of Cambrai and St Quentin, from

27 September until 10 October. The French First Army attacked on the right of

the British Fourth Army (Rawlinson). In view of the strength of this well-sited

and long-prepared position, Rawlinson and his artillery commander Budworth decided

on an intense fifty-six hour preliminary bombardment in addition to the

now-usual predicted crash and creeping barrage starting at zero hour on 29

September. Over 1,630 guns were used on a 10,000-yard front, firing an

extremely effective counter-battery and destructive programme beforehand, with

a high proportion of high-explosive shell, and neutralizing fire during the

attack. Operational and artillery planning was helped by a set of captured

enemy defence maps, showing all the trenches, pill-boxes, dugouts, machine gun

emplacements, battery positions, etc. The German defenders were stunned by the

artillery, and overwhelmed by the attack.

In ten days of heavy fighting in the crucial sector from St

Quentin to Epéhy, and especially north of this on a four-mile frontage between

Bellicourt and Vendhuille, where the St Quentin Canal ran in a tunnel, the

British and Americans eventually broke through the last and strongest of the

Germans’ fully prepared positions. A critical situation initially developed in

the tunnel sector when the American 2nd Corps’ two divisions (27th and 30th),

supported by three Australian divisions, were delayed by the strength of the

German defences and lost the barrage. Tanks became ditched in the deep

trenches, and as the inexperienced Americans neglected the vital task of

‘mopping up’ German pockets as they went forward, the Australians had to fight

through this ground again as they in turn moved up. Further south, at

Bellenglise, the British 46th Division managed to cross the canal, using rafts

and lifebelts, protected by a pulverizing barrage, punching a three-mile gap in

the German defence and turning the enemy flank to the north in the sector

facing the Australians and Americans. Advances were also made further north, on

27 September, between Péronne and Lens, on the fronts of the British Third and

First Armies, and by 5 October the attacking Allied armies had broken through

the whole Hindenburg Position. This opened the way for a war of movement and an

advance towards the vital main German communications routes.

This group of assaults was undertaken in three phases. First

came the storming of the Canal-du-Nord position on the left in the Battle of

the St Quentin Canal, and the advance on Cambrai. Following this came the

shattering blow which, after a stupendous artillery bombardment and with the

help of hundred of tanks, broke through the Hindenburg Line and turned the

defences of St Quentin. Lastly came the exploitation of these successes by a

general attack on the whole front which broke through the last of the enemy

defences and captured the Beaurevoir Line, to the rear of the Hindenburg Line,

and the high ground above it, by 10 October. The Germans were forced to

evacuate Cambrai and St Quentin and pull back to the river Selle. These three

battles created a huge salient in the German position.

Fifth Battle of Ypres

and Battles of Courtrai, Selle and Maubeuge

Meanwhile, further north, in the Fifth Battle of Ypres on 28

and 29 September, King Albert of Belgium’s Army Group of twelve Belgian

divisions, Plumer’s Second Army (ten British divisions), and Degoutte’s Sixth

Army (six French divisions) forced the Germans back from Ypres and drove yet

another salient into their lines, endangering the German position on the

Belgian coast. In one day these armies swept over the ground that had taken two

British armies, assisted by a French army, three months to capture the previous

year.

Meanwhile Ludendorff, receiving news on 28 September of the

Bulgarian request for an armistice, and after the Allied attack in Flanders had

begun, suffered a temporary mental and physical collapse, a crisis of nerve in

which he crashed to the floor and even foamed at the mouth. The succession of

gloomy reports from the Western Front can hardly have helped. At 6 p.m. he told

Hindenburg that an armistice was imperative. On the twenty-ninth, an armistice

on the Macedonian front was signed with the defeated Bulgarians and the way was

now open for an Allied attack from the south into Austria. Hindenburg, at a war

council meeting, told the German leaders that, to prevent a catastrophe (this

was the day the Hindenburg Line was broken), peace must be sought using

Wilson’s ‘fourteen points’ as a basis. Ludendorff now realized the game was up

and, while he found six divisions to putty up the Serbian front, started to

prepare the ground for peace proposals. On 3 October the Germans asked

President Wilson for an immediate armistice.

Meanwhile the success at Ypres was extended by the Battle of

Courtrai, from 14–31 October, which widened and deepened this wedge and

resulted in the capture of Halluin, Menin and Courtrai. This series of great

battles had, as their immediate result, in the south the evacuation of Laon and

the German retirement to the river Aisne; in the centre the withdrawal to the

river Scheldt, which liberated Lille and the great industrial district of

northern France around Roubaix and Tourcoing; and in the north the clearing of

the Belgian coast, including the submarine bases of Ostend, Zeebrugge and

Bruges. The Germans were now back on the line of the Scheldt and Selle rivers.

The Battle of the Selle, from 17–25 October, forced the Germans from the latter

and drove yet another wedge into their defences. Germany’s remaining allies

were now falling away; Turkey signed an armistice on 30 October, and

Austria–Hungary did the same on 4 November, after which Germany was isolated.

The Battle of the Selle was followed by the final blow, the

Battle of Maubeuge, from 1–11 November, which struck at and broke the Germans’

last important lateral communications, turned their positions on the Scheldt

and forced them to retreat rapidly from Courtrai. At the same time, the

Americans attacked again, the French armies were cautiously moving forward

(Foch was naturally unwilling for too much French blood to be spilled at this

stage), and the British had not halted in their series of successful

operations. This victory completed the achievement of the great strategic aim

of the whole series of battles, by effectively dividing the German forces into

two, one part on each side of the natural barrier of the Ardennes forest. The

German fleet had mutinied on 29 October, while the German army, while it had

been experiencing increasing indiscipline and desertion in the latter part of

1918, had been comprehensively defeated in the field. Revolution broke out in

Berlin. The pursuit of the beaten enemy all along the line was only halted by

the Armistice at 11 a.m. on 11 November. The Kaiser abdicated on 9 November,

and the following day the desperate German authorities told their armistice

delegation to accept any terms put in front of them. Fittingly, the Canadians

entered Mons, where the BEF had fought its first battle in 1914, on the morning

of the eleventh.