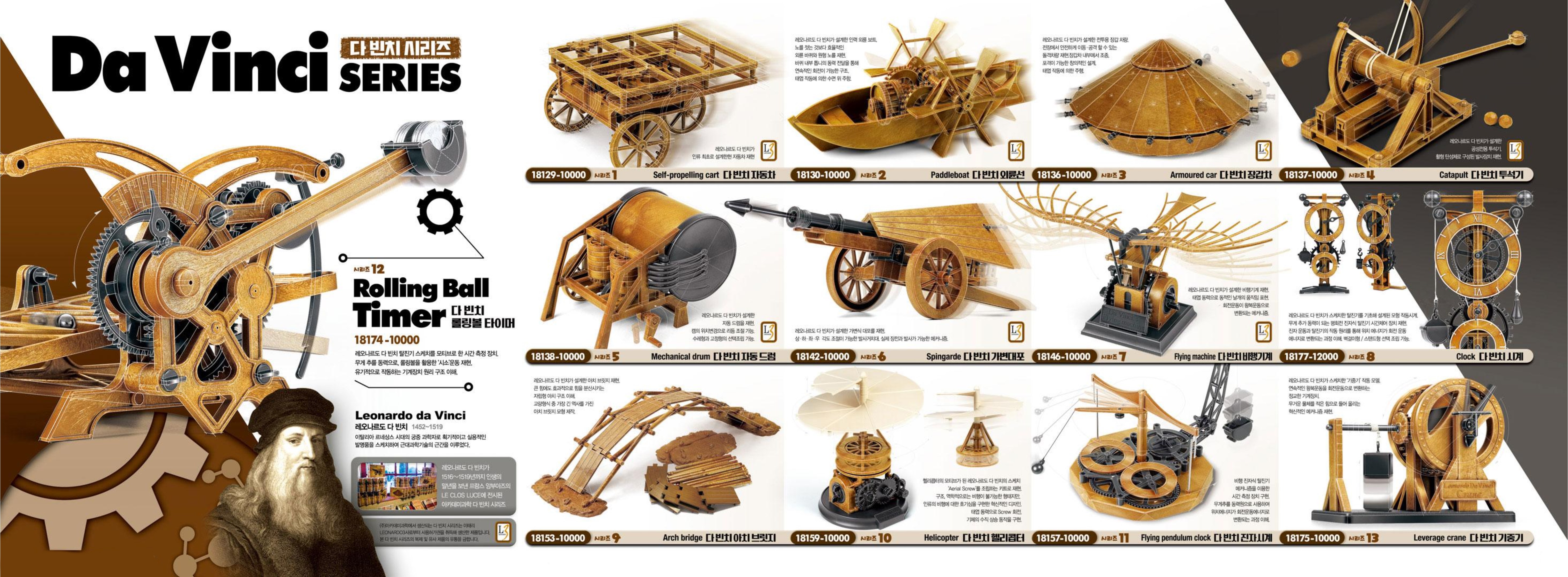

Giant crossbow

A letter from the west coast of India addressed to the

Florentine regent Giuliano de’ Medici in 1515 is revealing. A seafarer named

Andrea Corsali reported that he had discovered gentle people clad in long robes

who lived on milk and rice, refused any food that contained blood, and would

not harm any living creature—“just like our Leonardo da Vinci.” Corsali was

describing the Jains, known for their extreme nonviolence; in the twentieth

century they would have a profound influence on Mahatma Gandhi.

One of Vasari’s loveliest anecdotes about Leonardo concerns

the artist’s love of animals: “Often when he was walking past the places where

birds were sold, he would pay the price asked, take them from their cages, and

let them fly off into the air, giving them back their lost freedom.” Did

Leonardo, who had an exceptional desire for freedom and himself tried to fly,

feel a special rapport with birds?

Of course Corsali would not have been reminded of the artist

far away if Leonardo’s attitude had not seemed so remarkable. That a person

would display empathy at all was quite unusual in this era, which had been

devastated by violence. But the idea of actually forswearing the consumption of

meat out of simple consideration for other creatures was unheard of in the

West.

Vasari, who later wrote a biography of Leonardo, may have

known these and other reports about customs in the Orient. In the Buddhist

countries of Southeast Asia birds are offered for sale in front of some temples

even today so that people who want to ensure good karma can buy their freedom

and send them soaring into the air. Vasari’s account of Leonardo’s bird

liberation may have been no more than an appealing embellishment to his text.

Still, there is no doubt that Leonardo had a deep-seated

aversion to all violence, as several passages in his notebooks confirm. His

attitude certainly had more in common with the ethos of Eastern nonviolence

than with the harsh customs then prevalent in the Christian West. Precisely

because he respected the value of every creature, he was firmly convinced of

the sanctity of human life. In reference to his anatomical studies, he wrote:

“And thou, man, who by these my labours dost look upon the marvelous works of

nature, if thou judgest it to be an atrocious act to destroy the same, reflect

that it is an infinitely atrocious act to take away the life of man.”

Scythed chariot

Leonardo’s words make it difficult to grasp the gruesome

fantasies his mind was capable of in designing his engines of war. On hundreds

of pages, Leonardo sketched giant crossbows, automatic rifles, and equipment to

bombard strongholds with maximal destructiveness. The sole function of these

devices was to kill and destroy. He did not just record the technology, but

provided graphic descriptions of the devastating impact of his inventions. In

one sketch, archers are running away from an exploding grenade, which Leonardo

referred to as “the deadliest of all machines.”4 In another, a war chariot with

rotating scythes as large as men is mowing down soldiers and leaving behind a

trail of severed legs and dismembered bodies.5 The battle plans Leonardo drew

up are equally chilling. On Sheet 69 of Manuscript B, housed in Paris, we read

about his preparations for chemical warfare:

Chalk, fine sulphide of arsenic, and powdered verdigris may

be thrown among the enemy ships by means of small mangonels. And all those who,

as they breathe, inhale the said powder with their breath will become

asphyxiated. But take care to have the wind so that it does not blow the powder

back upon you, or to have your nose and mouth covered over with a fine cloth

dipped in water so that the powder may not enter.6

His involvement in the wars of his era extended well beyond

the design of weapons and began even before he signed on with the in – famous,

bloodthirsty Cesare Borgia in 1502. How could a man whose sense of empathy is

said to have inspired him to free birds from their cages come up with ideas of

this sort?

On one occasion, Leonardo justified his military activities

with a statement that a modern-day reader could easily picture coming straight

from the Pentagon: “When besieged by ambitious tyrants, I find a means of

offense and defense in order to preserve the chief gift of nature, which is

liberty.”

Doubts are certainly warranted here; after all, his first

employer, Ludovico Sforza, was not exactly a champion of freedom. The historian

Paolo Giovio, a contemporary of il Moro, called him “a man born for the ruin of

Italy.” That might sound harsh, but without a doubt, “the Moor” was a major reason

that Italy lost its freedom for centuries and became a battlefield for foreign

powers.

Ludovico, an inveterate risk-taker, sized up his position on

his very first day in power and realized that he was surrounded by enemies. In

his own empire his right to rule was in dispute, since he owed his power to the

violent murder of his brother, for which no one had been charged, and the

arrest of the sister-in-law. Moreover, Venice and the Vatican tried to exploit

Ludovico’s insecure position, and they armed for war. In March 1482, the

Venetians attacked Ferrara, which was an ally of il Moro. At this time,

Leonardo arrived in Milan and in his famous ten-point letter of application

promised il Moro a whole new arsenal of weapons. Two years later, Ludovico was

able to defeat the Venetians.

But il Moro, who was focusing all his efforts on

legitimating his rule once and for all, needed a seemingly endless supply of

weapons. Over the next few years, his dodges would determine not only the

further course of Leonardo’s unsettled life but also result in the so-called

Italian Wars, which lasted sixty-five years and brought about the political

collapse of the country.

The disaster ran its course when Ludovico sought a strong

ally against Naples. The king of Naples, Ferdinand I, had meanwhile given his

daughter’s hand in marriage to the legitimate heir to the throne in Milan, Gian

Galeazzo, and was quite indignant when he realized that Ludovico had no

intention of ceding power to his son-in-law. Ludovico encouraged Charles VIII of

France to invade Italy to overthrow Ferdinand. What followed was a bloody

farce: Charles was asked to invade Lombardy with forty thousand soldiers,

whereupon Gian Galeazzo was murdered. Two days later, Charles declared il Moro

the legitimate duke of Milan. But the latter showed no gratitude. When the

Neapolitans rebelled against the French occupation in the following year, the

opportunist switched sides and entered into an alliance with Venice and the

pope. The French were expelled and suffered great losses.

Just a few decades earlier, wars had been highly ritualized

battles with relatively few casualties, but now they were developing into

horrific bloodbaths. The handgun had been widely adopted; a few years later,

Leonardo would contribute a wheel lock, which was one of the handgun’s first

effective firing mechanisms. And there were growing numbers of portable cannons

on battlefields. Since the earlier stone balls had been replaced by metal

projectiles, the firearms shot more effectively than ever before, as Charles

VIII’s soldiers proved when they demolished the ramparts of the mighty castle

of Monte San Giovanni Campano with small cannons within hours, before attacking

Naples. Until then the battle was won by the side that had more and better

soldiers. From this point on, technology was key.

Leonardo had promised marvelous weapons to il Moro and was

granted a tremendous degree of freedom in return. As the engineer of the duke,

he received a fixed salary and no longer had to rely on selling his art on the

market. This was the only way he could pursue his research interests and

continue to perfect his paintings without any pressure to meet deadlines. We

owe the magnificence of the Milan Last Supper, the studies of water, and his

explorations of the human body to Leonardo’s clever move of offering himself up

to one of the most unscrupulous warlords of his era. During his first seventeen

years in Milan, serving Ludovico, he sketched the great majority of his

weapons, among them his most dreadful ones.

All the same, Leonardo’s interest in weapons went far beyond

the steady job they brought him. His drawings reveal an unmistakable

fascination with technology. In the end, his inventions were the product of his

inexhaustible fantasy, which gave rise to paintings, stories, projects to

transform entire regions, tools—and weapons. One of these weapons, which he

designed in Milan, looks like a water mill, but is actually a gigantic

automatic revolver. Leonardo arranged four crossbows in a compass formation,

with one pointing upward, one downward, one to the left, and one to the right.

The wheel was powered by four men running along its exterior to turn it at

breakneck speed. An ingenious mechanism with winches and ropes caused the bows

to tighten automatically with each turn. The marksman crouched in the middle of

the mechanism and activated the release. In one version, the wheel was equipped

with sixteen rather than four crossbows. Leonardo devoted himself to refining

the driving mechanism as well.

Even so, in comparison with the truly revolutionary firearms

of the era, this contraption looks charmingly old-fashioned. At least for the

years until 1500, Kenneth Clark was probably right in claiming that Leonardo’s

knowledge of military matters was not ahead of his time. Even Leonardo’s most

spectacular weapon, the giant crossbow he invented in 1485, was not really

pioneering. With a 98-foot bow span, this monster was intended to stand up to

cannons, to fire more accurately, and to save the soldiers from often fatal

accidents with exploding gunpowder. There is no evidence, however, that anyone

attempted to construct this giant crossbow during Leonardo’s lifetime. More

than five hundred years later, when a British television production undertook

this project, the results were pitiful. Specialized technicians were brought in

to build a functionally efficient weapon using twentieth-century tools, guided

by Paolo Galluzzi, one of the leading experts on Renaissance engineering. Since

they were required to restrict their materials to those that were available in

the Renaissance, they opted to build a bow with blades made of walnut and ash

that would be five times larger than any before. A worm drive designed by

Leonardo himself had to muster a force equivalent to the weight of ten tons to

tighten this enormous spring, thus making it possible to catapult a stone ball

over 650 feet. But when British artillerymen tried out the construction on one

of their military training areas, the balls barely left the weapon. After a

mere 16 feet in the air, they plopped to the ground. Video recordings showed

that they could not detach properly from the bowstring. When the technicians

added a stopping device to the string (not drawn by Leonardo), the range

increased to 65 feet— still hardly sufficient to produce anything but guffaws

on a Renaissance battlefield. And the fact that the replicators had made the

bow thinner than in Leonardo’s design came back to haunt them—the wood broke.

When you look at many of Leonardo’s drawings from his years

in Milan, it is hard to shake the feeling that Leonardo had no intention of

supplying serviceable weapons. It seems to have been far more important to him

to impress his patron—especially when he emphasized the enormous dimensions and

the impact of his weapons. As the most talented draftsman of his generation, he

knew how to create a dazzling effect. Leonardo enjoyed an outstanding

reputation as a technician of war because he was a great artist. He portrayed

the details of his designs so meticulously, using the effects of perspective,

light, and shadow so skillfully, that it was easy to mistake reality for wish.

The drawing of the giant crossbow features not only the knot of the string and

the details of the trigger mechanism, but also the soldier handling the weapon.

Like the face on the Mona Lisa, Leonardo’s war machines seem alive.

THE PHYSICS OF DESTRUCTION

While Leonardo proved a master of illusion in designing

weapons, he also made concrete contributions to military development. Military

commanders needed to figure out how to put the latest firearms—mobile

cannons—into action. How should they shoot? With bows and crossbows, the

shooter simply aimed straight ahead; the range of the new firearms, by

contrast, meant that the trajectory curve had to be determined to make the

cannonball hit its target. But no one had a clear idea about the laws governing

the paths of cannonballs. Progress on this matter could determine the outcomes

of wars.

Traditional physics offered little help, because this

discipline still adhered to the ancient view that a body moves only while a

force acts on it. But if that were so, a cannonball would come to a standstill

just after leaving the barrel of the cannon. The seemingly plausible concept of

“impetus” was introduced: The cannon gives the ball its impetus, and only when

the impetus is completely used up as it flies through the air does it fall to

the ground. The cannoneers of the time were well aware that the impetus theory

could not be correct; anyone who relied on it was off the mark. The error is

that gravity sets in immediately to begin pulling down on the cannonball.

Leonardo’s interest in this question went far beyond its

military implications. He was determined to figure out the laws of motion. He

kept going around in circles because he could not relinquish the idea of

impetus and because the crucial concept of the earth’s gravity was still

unknown at the time. His notebooks document how bedeviled he was by the laws of

motion. His explanations of mechanics were riddled with inconsistencies; at

times he argued both for and against impetus within the space of a single

paragraph.

But then he had a brilliant idea of how to determine the

trajectory of projectiles not by conceptualizing, but by observing: “Test in

order to make a rule of these motions. You must make it with a leather bag full

of water with many small pipes of the same inside diameter, disposed on one

line.” One sketch shows the small pipes in the bag pointing upward at various

angles, like cannons that aim higher at some points and more level at others.

The arcs formed by the spurting water correspond to the trajectories of the

cannonballs. Leonardo’s trajectories were accurate in both this sketch and

others. By means of a clever experiment—not involving mathematics—he had

discovered the ballistic trajectory that Isaac Newton finally worked out

mathematically some two hundred years later.

This little sketch offers a glimpse inside Leonardo’s mind.

He was able to link together fields of knowledge that appeared utterly unrelated.

From the laws of hydraulics, which he had investigated so exhaustively, he

gained insights into ballistics. His thoughts ran counter to the conventional

means of solving problems. Instead of attacking the matter head on, formulating

the question neatly, and penetrating more and more deeply below the surface,

Leonardo approached the problem obliquely—like a cat burglar who has climbed up

one building and from there breaks into another across the balconies. Leonardo

was unsurpassed in what is sometimes called “lateral thinking,” which enabled

him to explain the sound waves in the air by way of waves in the water, the

statics of a skeleton by those of a construction crane, and the lens of the eye

by means of a submerged glass ball.

Leonardo’s experiments with models also represented a new

approach. Since he neither understood how to use a cannon nor was able to

observe the trajectory of an actual cannonball up close, he used a bag filled

with water as a substitute. Of course an approach of that sort is unlikely to

yield a coherent theoretical construct, because similarities between different

problems are always limited to individual points, and Leonardo was far too

restless to pursue every last detail of a question. Still, his models yielded

astonishing insights. The French art historian Daniel Arasse has aptly called

him a “thinker without a system of thought.”

In an impressive ink drawing, Leonardo illustrated the

damage that could be inflicted by applying his insights into ballistics. A

large sheet in the possession of the Queen of England shows four mortars in

front of a fortification wall firing off a virtual storm of projectiles. Not a

single square foot of the besieged position is spared from the hundreds of

projectiles whizzing through the air. For each individual one, Leonardo marked

the precise parabolic trajectory, and the lines of fire fan out into curves

like fountains. Ever the aesthete, Leonardo found elegance even in total

destruction.

Saturation bombing of

a castle

It is difficult to establish to what extent Leonardo’s

knowledge of artillery was implemented on an actual battlefield. When Ludovico

had Novara bombarded in February 1500, the mortars were so cleverly positioned

that the northern Italian city quickly fell. In the opinion of the British

expert Kenneth Keele, il Moro was using Leonardo’s plans for a systematic

saturation bombing.

Leonardo’s close ties to the tyrants of his day offer a case

study of the early symbiosis of science and the military. Now as then, war not

only provides steady jobs and money to pursue scholarly interests, but also

prompts interesting theoretical questions. Even a man as principled as Leonardo

was unable to resist temptations of this sort. He was not the first pioneer of

modern science and technology to employ his knowledge for destructive aims.

Half a century earlier, Filippo Brunelleschi, the inspired builder of the dome

of the Florence Cathedral, had diverted the Serchio River with dams to inundate

the enemy city of Lucca. (This operation came to a disastrous end; instead of

putting Lucca under water, the Serchio River flooded the Florentine camp.)

Leonardo’s struggle to strike a balance between conscience, personal gain, and

intellectual fascination seems remarkably modern, and brings to mind the physicists

in Los Alamos who devoted themselves heart and soul to nuclear research until

the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima.

Of course we cannot measure Leonardo’s values by today’s

standards. We have come to consider peace among the world’s major powers a normal

state of affairs now that more than six decades have passed since the end of

World War II, but we need to bear in mind that there has never been such a

sustained phase of freedom from strife since the fall of the Roman Empire. In

Italy, the Renaissance was one of the bloodiest epochs. The influence of the

Holy Roman Empire had broken down, mercenary leaders had wrested power from

royal dynasties, and a desire for conquest seemed natural. War was the norm,

and a prolonged period of peace inconceivable.

Leonardo’s refusal to regard death and destruction as

inescapable realities is a testament to his intellectual independence from his

era. As far back as 1490 he was calling war a “most bestial madness.” And one

of his last notebooks even contains a statement about research ethics. While

describing a “method of remaining under water for as long a time as I can

remain without food,” he chose to withhold the details of his invention (a

submarine?), fearing “the evil nature of men who would practice assassinations

at the bottom of the seas by breaking the ships in their lowest parts and

sinking them together with the crew who are in them.” The only specifics he

revealed involved a harmless diver’s suit in which the mouth of a tube above

the surface of the water, buoyed by wineskins or pieces of cork, allows the

diver to breathe while remaining out of sight.

Leonardo must have had his reasons for withholding

particulars about the dangerous underwater vehicle. Perhaps his ideas were

still quite vague, or he was afraid that imitators might thwart his chances for

a promising business. But the key passage here is Leonardo’s statement about

the responsibility of a scientist. He was the first to assert that researchers

have to assume responsibility for the harm others cause in using their

discoveries. Insights like these, and his high regard for each and every life,

were quite extraordinary at the time. It is amazing that he embraced these

ethical principles—but not surprising that he repeatedly failed to live up to them,

at least by today’s standards.