In a telegram to Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm’s

headquarters on 4 August, Moltke reiterated that he was seeking to “bring

the operations of [the Second and Third] Armies into consonance.” Both

armies must advance to join in “the direct combined movement” against

Louis-Napoleon’s principal army. General Leonhard Graf von Blumenthal [chief of

staff of the Prussian 3rd Army] and the crown prince complied, pushing their

army steadily westward in the first days of August. Moltke landed his first

blow in Alsace, where the Prussian Third Army rammed into Marshal Patrice

MacMahon’s I Corps in two stages, a small “encounter battle” at

Wissembourg on 4 August and an orchestrated clash at Froeschwiller two days

later. Although MacMahon commanded a “strong corps” of 45,000 men –

“strong” because it contained four divisions instead of the usual

three – the marshal had strong responsibilities. Expected to hold the line of

the Vosges, threaten the flank of any Prussian attack toward Strasbourg,

maintain contact with Douay’s VII Corps in Belfort, yet never lose touch with

the Army of the Rhine to his north, the marshal needed every man that he had,

and then some.

To cover his vast sector of front, MacMahon placed his four

divisions in a wide square, one division and headquarters at Haguenau, a second

division at Froeschwiller, a third at Lembach, and a fourth at Wissembourg, a

charming little village on the Lauter river, which was France’s border with the

Bavarian Palatinate. By means of this rather ungainly placement of his

divisions, MacMahon simultaneously defended the border with Germany, kept

contact with Failly’s V Corps, and still had two divisions far enough south to

threaten the flank of any Prussian push toward Strasbourg or Belfort. Still,

ten to twenty miles of rough country separated each of the four French

divisions, a dangerous separation partly necessitated by shortages of food and

drink, which forced MacMahon to scrounge among the local population. If

MacMahon took the initiative, he would have time to close the gaps and join the

units in battle. But if MacMahon were attacked on any of the corners of his

square, none of the French divisions would have time to “march to the

sound of the guns.” They were too far apart, a fact brutally driven home

to the 8,600 troops of MacMahon’s 2nd Division at Wissembourg on 4 August.

Marshal MacMahon’s 2nd Division, commanded by

sixty-one-year-old General Abel Douay – Felix Douay ‘ ‘s brother and president

of the military academy at St. Cyr before the war – had only arrived in

Wissembourg late on 3 August. MacMahon hurriedly shoved Douay forward after

receiving Leboeuf’s vague warning of “a serious affair.” Although the

French had built Wissembourg into a formidable defensive line in the eighteenth

century – a network of towers, moats, redoubts, and trenches along the right

bank of the Lauter – Marshal Niel had abandoned the fortifications in 1867,

removing their guns and maintenance budgets. Decay followed swiftly in the

warm, moist shelter of the Vosges: A war correspondent at Wissembourg in 1870 found

the walls crumbling, the moats filled with weeds and rubbish, the glacis

already sprouting elms and poplars. Still, the place had considerable tactical

importance if the Germans came this way. Wissembourg was an important road

junction for Bavaria, Strasbourg, and Lower Alsace and, after looking it over,

General Douay’s engineers recommended that Wissembourg be cleaned up and

defended as a “pivot and strongpoint” for operations on the frontier,

a recommendation that Douay passed back to I Corps headquarters. Ultimately, Douay’s

great misfortune was to have landed at the last minute in the exact spot chosen

by Moltke for the invasion of France. Seeking to pin the Army of the Rhine with

his First and Second Armies while swinging Third Army into Napoleon III’s

flank, Moltke wired Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm late on 3 August: “We

intend to carry out a general offensive movement; the Third Army will cross the

frontier tomorrow at Wissembourg.”

The Prussian Third Army’s seizure of Wissembourg on 4 August

was as good an indictment of French intelligence and reconnaissance in the war

as any. When General Douay inspected the town on 3 August, he had no inkling that

80,000 Prussian and Bavarian troops were closing rapidly from the northeast in

response to the Prussian Crown Prince’s order of the day: “It is my

intention to advance tomorrow as far as the River Lauter and cross it with the

vanguard.” Indeed the Prussians had been masters of the Niederwald, the

sprawling pine forest that ran along both banks of the Lauter and cloaked the

Prussian approach, for weeks. French infantry officers could not recall a

single French cavalry patrol entering it. What intelligence Douay received on 3

August came not from the French cavalry, but from Monsieur Hepp, Wissembourg’s

subprefect, who warned that the Bavarians had already seized the Franco-German

customs posts east of the Lauter and that large bodies of German troops were in

the area. Still, Douay retired that evening without pushing his eight squadrons

of cavalry across the Lauter to reconnoiter. Only on the morning of the 4th did

Douay finally send a company of infantry across the river. No sooner had they

touched the left bank than they were thrown back by Prussian cavalry. This was

interpreted as nothing more serious than an “outpost skirmish” in the

French camp. Reassured, General Douay ordered morning coffee at 8:00 a. m. and

wired the results of his reconnaissance to MacMahon at Strasbourg. Relieved

that there was still time to mass his corps on the frontier, MacMahon made

plans to move his headquarters to Wissembourg the next day. Even as his

telegraph operators tapped out this intention to Leboeuf at Metz, the first

Prussian shells were exploding in Wissembourg and General Friedrich von

Bothmer’s Bavarian 4th Division was splashing across the Lauter. In the Chateau

Geisberg, Abel Douay’s, hilltop headquarters above Wissembourg, confusion was

total.

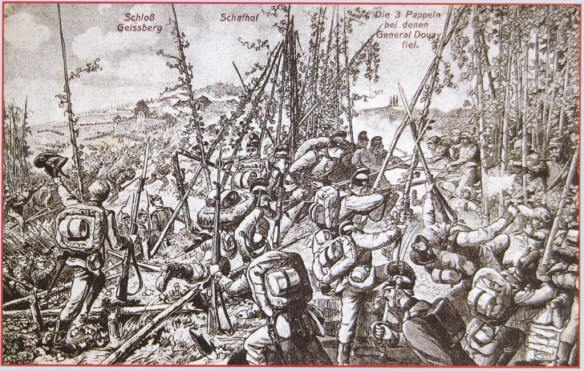

Central forts of the “Wissembourg lines” in the

eighteenth century, the twin towns of Wissembourg and Altenstadt still

possessed redoubtable fortifications for an infantry fight: moats, loopholed

stone walls and towers, and an elevated bastion just behind and to the right on

the Geisberg. Douay had posted two of his eight battalions, six guns, and

several mitrailleuses in the riverfront towns of Wissembourg and Altenstadt on

the 3rd. He arrayed the rest of his infantry, his cavalry, and twelve cannons

on the slopes above the twin towns. As the Bavarians swarmed over the Lauter,

every French gun, deployed in a line from Geisberg on the right along to

Wissembourg on the left, poured in a seamless curtain of fire. The French

infantry, all veterans with Chassepots, adjusted their sights and commenced

firing with devastating effect. Nikolaus Duetsch, a Bavarian lieutenant

casually inspecting his platoon in Schweigen on the left bank of the Lauter,

recalled his amazement when one of his infantrymen suddenly threw up his arms and

cried, “Ich bin geschossen” – “I’m hit!” And he was.

“The bullet came from the Wissembourg walls, more than 1,200 meters

away.” Closer in, every French bullet struck home as the Bavarians,

emerging from the morning fog in their plumed helmets, struggled through

thickly planted vineyards and acacia plantations to reach the Lauter.

For the first time, the Bavarians heard the tac-tac-tac of

the mitrailleuse. These rather primitive “revolver cannon” did not

traverse their fire across the field like late nineteenth-century machineguns,

rather they tended to fix on a single man and pump thirty balls into him,

leaving nothing behind but two shoes and stumps. Needless to say, the gun had a

terrifying impact out of all proportion to its quite meager accomplishments as

a weapon. (“One thing is certain,” a Bavarian infantry officer wrote

after the battle, “few are wounded by the mitrailleuse. If it hits you,

you’re dead.”) Johannes Schulz, a Bavarian private hustling toward

Altenstadt, later described the carnage in the Bavarian lines. The French

artillery and rifle fire was so intense and accurate that every Bavarian

attempt to form attack columns on the broken, marshy ground before Wissembourg

was shot to pieces. Schulz’s own platoon leader was punched to the ground by a

bullet in the chest; miraculously, he rose from the dead, saved by his rolled

greatcoat, which had stopped the bullet. As the Bavarians wavered, Schulz

recalled the blustery appearance of his regimental colonel, whose shouted

orders showed just how deeply Prussian tactics had penetrated the Bavarian army

in the years since 1866: “Regiment! Form attack columns! First and light

platoons in the skirmish line! Swarms to left and right!” That first

attempt to cross the Lauter and break into Wissembourg was brutally cut down by

the Turcos of the 1st Algerian Tirailleur Regiment, who worked their Chassepots

expertly from the ditch, the town walls, and the railway embankment, which

formed an impenetrable rampart along the front and eastern edge of Wissembourg.

Though ten times stronger than the defenders, the Bavarians wilted, the

officers shouting “nieder!” – “get down!” – the wild-eyed

men breaking formation and crawling away in search of cover, terrified by their

first sight of African troops. Schulz remembered the conduct of his battalion

drummer boy; shot cleanly through the arm, the boy screamed over and over,

“Mein Gott! Mein Gott! Ich sterbe furs Vaterland! ” ” – “My

God, my God! I’m dying for our Fatherland!”

It had rained in the night and the morning was hot and

humid; fog rose from the fields. Most of the Bavarians and Prussians, hacking

their way through man-high vines, recalled never even seeing the French; they

merely heard them, and fired at their rifle flashes. Adam Dietz, a Jager ”

armed with Bavaria’s new Werder rifle, every bit as good as the Chassepot,

bitterly concluded that the Prussian tactic of Schnellfeuer – “rapid

fire” – was impossible when the troops were lying prone: “Rapid fire

is not so rapid when you’re lying flat because it takes so long to reload; you

have somehow to reach into your cartridge pouch, find a cartridge with your

fingers, eject, load, aim, and only then, fire.” Clearly the French – the

Turcos and two battalions of the 74th Regiment – were having a better time of

it, standing behind cover in Wissembourg and Altenstadt, loading, aiming, and

firing as quickly as they could. Only the Prussian and Bavarian artillery

limited the losses. Several German guns crossed the Lauter on makeshift bridges

and joined the infantry assault, blasting rounds into the wooden gates at close

range and giving an early glimpse of the bold tactics conceived after Koniggr

” atz. The rest, deployed on the ” left bank of the Lauter, shot

Wissembourg into flames, dismounted the mitrailleuses, and pushed the French

riflemen off the town walls. For this, they could thank the French artillery;

firing an unreliable, time-fused projectile and standing too far back from the

action, the French guns, after some initial success, caused little damage on the

Prussian side. Still, with the outskirts and canals of Wissembourg choked with

Bavarian dead, it was an inauspicious start to the war.

Luckily for thirty-nine-year-old Crown Prince Friedrich

Wilhelm, Prussian tactics never relied on frontal attacks. They groped always

for the flanks and the line of retreat, and Wissembourg was no exception to

this rule. Even as Bothmer’s division foundered in Wissembourg and Altenstadt,

General Albrecht von Blumenthal, the Third Army chief of staff, was directing

the Bavarian 3rd Division against the French left and swinging the Prussian V

and XI Corps into Douay’s right flank and rear. From the rising ground behind

the Lauter, Blumenthal and the crown prince could make out Douay’s tent line

with the naked eye. It was clear that the French general had no more than a

division with him, and that he was dangerously exposed, what soldiers called

“in the air,” with no natural features protecting his flanks, no

reserves, and no connection to the other divisions of I Corps.

Abel Douay did not live to recognize the utter hopelessness

of his situation. Riding out to assess the fighting in Wissembourg, he was

killed by a shellburst as he stopped to inspect a mitrailleuse battery at 11 a.

m. By then the Prussian envelopment was nearly complete. The Prussian 9th

Division, leading the V Corps into battle, had crossed the Lauter at St. Remy,

taken Altenstadt, and stormed the railway embankment at Wissembourg, taking the

embattled Algerians between two fires. Six more Bavarian battalions swarmed

across the Lauter above Wissembourg, closing the ring. Though surrounded, the

French held on, blazing away along the full circumference of their narrowing

ring on the Lauter, while the French batteries above fired as quickly as they

could into the swarms of Bavarians and Prussians on the riverbank. Ultimately

it was the Wissembourgeois, not the French troops, who ran up the white flag.

Faced with the certain destruction of their lovely town, the inhabitants

emerged from their cellars and demanded that the 74th Regiment open the gates

and let the Germans in. Here was an early instance of the defeatism that would

plague the French war effort from first to last. Major Liaud, commander of the

74th’s 2nd battalion, bitterly recalled the interference of the townsfolk, who

pleaded with his men to end their “useless defense” and refused even

to provide directions through their winding streets and alleys. When Liaud sent

men onto the roofs of the town to snipe at the Germans, he was scolded by the

mayor, who reminded him that the French troops “were causing material

damage” and needlessly prolonging the battle. The battle ended abruptly

when a crowd of determined civilians advanced on the Haguenau gate, lowered the

drawbridge, and waved the Bavarians inside.

If victory belonged to the Germans, it was not immediately

apparent to the troops. Indeed the brave French stand in Wissembourg knocked

the wind out of the Bavarians, and left them gasping for most of the afternoon,

leaving the Prussians to complete the envelopment. Captain Celsus Girl, a

Bavarian staff officer who rode back from the Lauter at the climax of the

battle, was amazed to discover the roads east of the river clogged with

Bavarian stragglers (Nachzugler) too frightened by the sounds of battle to

advance. “There were clusters of men beneath every shade tree on the

Landau Road . . .. Most were just scared, trembling with `cannon fever’ . . ..

Nothing would move them; they answered my best efforts and those of the march

police with passive resistance.” And this was the better of the two

Bavarian corps; after inspecting General Ludwig von der Tann’s Bavarian I Corps

before the battle, Blumenthal and the crown prince had judged it incapable of

fighting and left it in reserve, far behind the Lauter. Though the Bavarians

were a disappointment, raw German troop numbers carried the day. As the French

guns and infantry on the Geisberg tried to disengage their embattled comrades

below prior to a general retreat, they were themselves engulfed by onrushing

battalions of the Prussian V and XI Corps, which worked around behind the

Geisberg, pushed the French inside the chateau, and then stormed it.

Fighting raged for an hour, with French infantry, barricaded

inside every room and on the roof, firing into the masses of Prussians

assaulting the ground floor. Considering Prussia’s military reputation, a

French officer was appalled by the crudity of the Prussian attack: Wave after

wave of Prussian infantry broke against the walls of the chateau and its outbuildings.

The largely Polish 7th Regiment was mangled, losing twenty-three officers and

329 men. On the slopes below the Geisberg, Prussian, and Bavarian troops from

Wissembourg joined the attack, pushing uphill through the remnants of the

French 74th Regiment. A Bavarian sergeant took the Chassepot from the hands of

a French corpse on the hillside and was amazed to find the rifle sights set at

1,600 meters, an impossible shot with the Prussian needle rifle or the Bavarian

Podewils. The battle for the chateau stalled until gunners of the Prussian 9th

Division succeeded in wrestling three batteries onto an undefended height just

800 paces from the Geisberg. At that range they could not miss, and white flags

shortly appeared on the roof. Among the casualties of this last bombardment was

the Duc de Gramont’s brother, colonel of the French 47th Regiment, whose left

arm was ripped off by a shell splinter. Two hundred Frenchmen surrendered as

the rest of Douay’s division fled westward, abandoning fifteen guns, four

mitrailleuses, all of the division’s ammunition, and 1,000 prisoners. Abel

Douay, by now a rigid corpse on a table in the Chateau Geisberg, had never

stood a chance. He had stood in a bad position against twenty-nine German

battalions with just eight of his own. Marshal MacMahon did not learn of the

disaster until 2:30 p. m., when he resolved to collect the survivors of Douay’s

division and lead a “fighting retreat” through the Vosges passes to

Lemberg and Meisenthal, where he would be better positioned to unite with the

Army of the Rhine and Canrobert’s VI Corps. The collection point would be a

little village on the eastern edge of the Vosges called Froeschwiller.