Recruitment and

Obligation

The words used by Anglo-Saxons themselves for ‘army’ vary between the word ‘fyrd’ and the word ‘here’. Historically the word fyrd (from ‘faran’–to travel) has been taken to mean ‘an expeditionary force’, which may not in essence be correct. The contexts in which the words here and fyrd are used in the contemporary texts tend to point to the Anglo-Saxon fyrd being a defensive type of army and the here being an offensive kind. Both Danish and English armies could be described as a here provided they were somehow on the offensive. Few subjects, however, are more obscure and controversial in the world of Anglo-Saxon military studies as that of how the fyrd of the Later Anglo-Saxon era was supplied with its men.

It was the right of an Anglo-Saxon freeman to bear arms.

Central to the historic arguments over how Anglo-Saxon armies were formed was

the role of the ‘ceorl’, the free peasant warrior. Ideas varied for centuries

as to whether an Anglo-Saxon army was essentially one of noble warriors who

were summoned by the king in return for land and privileges, or whether it was

a general levy of able-bodied freemen, or even a mixture of both. These

arguments had their basis in political perceptions of the origins of

Englishness and the contemporary spin that people put on it. Was the

Anglo-Saxon army some sort of socialist utopia or a system more closely linked

to post-Conquest feudalism and aristocratic bonds? The view often held by

Victorian historians that the Anglo-Saxon army was somehow a ‘nation at arms’

is not generally accepted today but remnants of the idea of it still can be

found in the modern literature.

Historians have tried to address exactly how the mechanics

of military obligation worked. How would anyone be made to come to battle and

what would they do if they could not? It is now generally accepted that the key

to understanding how this worked is in acknowledging the mechanic that drove

the whole thing–the personal lordship bond. It has been argued, with growing

success, that the lordship ties that held society together were central to the

military process throughout the whole period.

In the early 1960s, Warren Hollister provided a seductive

solution to the whole problem, acknowledging the diversity of opinion on the

matter. The fyrd was not in fact one, but two things. There was a Great Fyrd

which consisted of a kind of poorly armed peasant ‘nation at arms’, and there

was a Select Fyrd consisting of semi-professional, well-equipped, land-owning

warriors whose obligations were based on the 5-hide land-holding unit. The

linchpin around which Hollister constructed his theory was a now widely quoted

passage in the Domesday Book for Berkshire: ‘If the king sent an army anywhere,

only one soldier went from five hides, and four shillings were given him from

each hide as subsistence and wages for two months. This money, indeed, was not

sent to the king but was given to the soldiers.’ Here, then, was the Select

Fyrdsman, a warrior supported by funding, whose duty was to attend the royal

host. The fact that he brought money with him hints at the likelihood that

there was somewhere arranged for him to spend it. But to find out why the

Berkshire thegn bothers at all to turn up for the king, we need to dig deeper

into history.

In the early Anglo-Saxon period, when a king summoned his

fyrd, he would expect his personal retainers (‘gesiðas’, or companions) to arm

themselves and would expect the duties of his ‘duguð’ (senior landed retainers

with a proven military track record) to be fulfilled. The duguð were men who

had served with their lord’s household throughout their youth and had been

rewarded with a little land themselves upon which to found their own group of

dependent men. Given the right circumstances, such a man could rise to become

as powerful as the lord he served. They would turn up for campaign with their

own retinues consisting of people who had received from them various gifts such

as rings, treasures and war gear. Above the duguð was a senior warlord for whom

all this was being done. Ultimately, the head of the kin group was the man

whose influence, wealth and gift-giving capabilities were the greatest. He was

the king. The very word ‘king’ comes from the Old English ‘cyning’, which means

‘chief of kinsmen’. Understandably, in a system such as this his power was

immense.

Law code 51 of King Ine of Wessex (688–726) spells out the

consequences of neglecting fyrd service: ‘If a gesiðcund man who holds land

neglects military service, he shall pay 120 shillings and forfeit his land; [a

nobleman] who holds no land shall pay 60 shillings; a cierlisc [free peasant]

shall pay 30 shillings as penalty for neglecting the fyrd.’ This law is thought

to reflect the structure of the earlier Anglo-Saxon armies in that when a king

called out his fyrd it would consist of his own landed companions, those who

owed service to these men through some other gift exchange, and the free

peasants who served them.

However, by the eighth century the rise in the power and

wealth of the Church had begun to throw a spanner in the works. The Church

required its land in perpetuity and not just for the lifetime of the king who

gave it. A system came into being called Bookland. This grant of land to the

Church came with no obligations from the Church to the king except, it seems,

for the securing of his soul in heaven. But for the king, it meant that the

land was permanently removed from his financial and administrative system and

given to his ultimate lord, God himself.

Bookland was a problem that took time to materialise but

which had inevitable consequences for the kings of middle Saxon England. The

more land you gave away free from military service dues, the smaller your

warrior base became and potentially your kingdom would become vulnerable to

other kings or raiders. The answer to the problem was found in the kingdom of

Mercia. King Æthelbald (716–57) decreed that churches and monasteries could

hold their land free from all dues except bridge building and the defence of

fortifications. The mighty King Offa (757–96) extended this to the

all-important fyrd duty. Thus, the three necessities, or ‘common burdens’, were

founded. These burdens became the bedrock of military recruitment across the

Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England until they were modified by Alfred the Great

(871–900) in his grand reforms of the ninth century.

At around the same time as the Bookland issue was being

resolved there was a change in terminology being employed. The duguð was a term

in decline and seems to have been replaced by the word ‘thegn’, which soon came

to be a widely used term across the country. The thegn held the Bookland from

the king in return for military service. The nobleman who held the large estate

known as the ‘scir’, or ‘shire’, would be the ealdorman.

So, the nature of recruitment on the eve of the Viking

invasions at the end of the eighth century was fairly straightforward. The

armies of Anglo-Saxon England ranged from small warbands of local thegns to

larger more territorial units commanded by ealdorman who were protecting their

shires. Above this was the royal host called out by the king himself which in

effect was made up of numerous groups of thegns, ealdormen and their retinues.

All of the constituent parts of these forces came to the battlefield through

the duties imposed upon them by lordship ties bound by a mixture of gift giving

and land tenure.

The activities of the larger hosts throughout this period

are well documented since they are the instruments of the king. Wars between

Saxon kingdoms such as Wessex and Mercia, or between Mercia and the Welsh

kingdoms, feature in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. But when Alfred the Great first

fought the Great Heathen Army alongside his brother King Æthelred I, the

chroniclers make a revealing statement about how armies were then organised.

The entry for 871 says that during that year there were nine ‘general’

engagements between the West Saxons and the Danes. This figure did not count

the expeditions that the king’s brother (Alfred), ealdormen and king’s thegns

often rode on. The message here is clear: senior noblemen, ealdormen and king’s

thegns were each capable of mounting their own military expeditions outside of

the activities of the royal host. The king’s host would of course take weeks to

gather together. Importantly, the chronicler mentions that these smaller forces

‘rode’ on their campaigns.

So, how did military provision change during Alfred’s reign?

The answer lies in the years after the watershed Battle of Edington (878) when

Alfred finally rid himself of Guthrum the Dane in a famous encounter. After

Edington, over the next two decades, Alfred instigated a series of fortified

places throughout his kingdom resulting in an entirely new type of defence: a

defence-in-depth system in which no two forts were more than around 20 miles

apart. The impact of these forts and how they were manned is examined below,

but the most important point of the reforms was that the fyrd was organised

into a three-part system.

We are told by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle in the entry for

894 in a passage that describes the strategic manoeuvring against the renewed

Viking threat in south-east England, that ‘The king had separated his army into

two so that there was always half at home and half out, except for those men

who had to hold the fortresses. The raiding army did not come out in full from

those positions more than twice.’ Ample evidence, then, for a system that had

its obvious benefits. With a strategically gifted commander such as Alfred, and

with numerous manpower resources spread deliberately over the landscape, the

new kingdom of the Anglo-Saxons was to be a well-defended place indeed. This

kingdom was born out of the combination of Wessex and the English parts of

Mercia. Eventually, it would expand under King Athelstan (924–39) to become the

Kingdom of the English. The new mechanism meant that there was always one part

of the force at home on their estates, another in the field at a state of

readiness and a third part on fortress duty. They could act in coordination

with one another or mount their own expeditions. It was a plan based on

Alfred’s own observations of the Carolingian model, which in itself probably

borrowed from a papal Italian arrangement for the defence of Rome. The point is

that it worked. Despite some notable problems when one Anglo-Saxon force’s tour

of duty had expired before its replacements could take over from it–as happened

in 893 at Thorney Island –it remains the case that the Anglo-Saxon armies of

southern England were vastly better organised than they had been when the

Vikings first descended upon Wessex.

Alfred’s reorganisation still required strong leadership to

put into action. Moreover, one fundamental thing remained unchanged and that

was the basic make-up of the fyrd. It still comprised the same people. The cost

of all this, however, was immense. Inevitably, the system was doomed to be a

hostage to neglect. After the reign of King Edgar (959–75) during which the

Anglo-Saxons had achieved an unprecedented level of power in the British Isles,

the recruitment system in part fell back upon makeshift levies based on land

tenures measured in hidage. The grand fortification schemes employed by Alfred,

his son Edward the Elder (900–24) and his grandson Athelstan (924–39) had in

places fallen into disrepair, leaving England vulnerable once again to Viking

attack. This is not to say that King Æthelred (979–1016) did not attempt to

rectify the situation–in fact, far from it. Æthelred’s attempted reforms,

particularly in respect of naval provision, were ambitious to say the least.

Between 1008 and 1013 the king instigated reforms which included the

construction across the country of a navy of around 200 ships and the provision

of mailcoats for thousands of warriors. However, all the time the king had to

pay increasingly burdensome sums of money to pay off the Danes and soon he even

took on a Danish contingent of his own which required feeding and provisioning.

The 5-hide unit is usually associated with a thegnly rank,

this being an amount of land that qualifies its holder in that rank. However,

it is clear from Domesday Book that there was great variety in the land-based

obligation, varying wildly from region to region. A nobleman holding just a few

hides might be required to provide a warrior, while an estate of well over 5

hides might only be obliged to provide just a single warrior. It depended on

the nature of the arrangement between the landholder and the king. If an estate

had to provide more than one warrior, the head of the estate would need to

recruit from his tenants or find a way of replacing what he could not provide

with a money payment so the king could hire a mercenary.

What seems not to have changed was the bond through lordship

that drove the obligation. As if to reinforce this notion at a time when

service seems to have been widely based on land-holding arrangements, the

Danish king of England Cnut (1016–36) came up with a stringent law for deserting

one’s lord:

Concerning the man who

deserts his lord. And the man who, through cowardice, deserts his lord or his

comrades on a military expedition, either by sea or by land, shall lose all

that he possesses and his own life, and the lord shall take back the property

and the land which he had given him. And if he has book-land it shall pass into

the king’s hand.

By the time of the Battle of Hastings, it is still the case

that King Harold’s army would have been recruited largely through the bond of

personal lordship ties. Land tenure based on the 5-hide unit certainly came

into it, but so too did the royal purse and the provision therein for mercenary

hire. While not as rigidly organised as the armies of the later Alfredian

period, those of 1066 were just as capable of providing results in the field.

What do we know, however, of how long it took any of these

armies to gather a force into the field? We have precious little evidence to

answer this question, but what little we do have points to the reasons why it

was so easy for Scandinavian coastal predators to achieve so much in a short

space of time. We know from the 871 Anglo-Saxon Chronicle entry that units of

mounted men under the command of local nobles were able to put into the field

almost immediately, but were small in number. Larger hosts, however, took

longer to gather. Alfred’s famous call to arms of 878 issued from Athelney to

the remainder of his core supporters in surrounding shires bore fruition in the

seventh week after Easter, but it is not certain when the call went out. It was

a nervous wait for Alfred, but when the men of Somerset, Wiltshire and parts of

Hampshire answered his call, they joined him at his camp at Egbert’s Stone and

were ready to march with him the next day to Illey Oak and thence to Edington.

The Danish assault on Norwich in 1004 gives a clearer idea.

The Danish force seems not to have been of a size that any mounted

rapid-reaction-style force could deal with. Instead, Ulfcytel Snilling, the

local East Anglian leader, was obliged to play for time by buying peace from

the army while he raised his force. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is specific that

Ulfcytel had not had time enough to gather his own army at this point. The

Danes stole away to Thetford and Ulfcytel’s order for their ships to be broken

up fell on deaf ears. It was three weeks since their first assault on Norwich

when the Danes torched and sacked Thetford. The following morning they prepared

to return to their ships when Ulfcytel’s East Anglians fell upon them, forcing

a battle. It was a hard-fought battle which Ulfcytel ultimately lost. However,

it is explicitly stated that had Ulfcytel’s numbers been up to full strength

the Danes would never have made it back to their ships. So it would seem then

that three weeks is barely enough time to raise a sizable force to match that

of the invader. This gives an idea as to the desperation of the year 1016–a

year of endemic warfare in England–when King Edmund Ironside was compelled to

call out the ‘national’ host at least five times for extensive campaigning.

The year of 1066 provides its own clues, although we have to

be mindful of the possibilities that Harold had with him at all times a

household force of a size enough to deal with all manner of problems, probably

in the form of his own and his brothers’ retinues and his Danish mercenaries.

Nevertheless, he decided to disband his army in the south of England on 8

September 1066, but then heard of the Norwegian invasion in the north and

arrived at Tadcaster on 24 September 1066. Similarly, on his dash to London–a

journey of some 190 miles–the passage of time is around two weeks, but it is

clear from the sources that this was not enough time for a full host to be

properly gathered. Harold’s reasons for his actions and his failure to wait at

London for reinforcements may be perfectly justified based on what his

strategic thinking was at the time, but once again the lesson is that two or

three weeks is barely enough for a full host to form.

Quite how the fyrd was mustered is another question that

puzzles historians. Messengers will certainly have been used, but did they use

any devices to show the king’s will? It has been suggested from very little

evidence that token wooden swords may have been used to symbolise a summons to

the host. This has been based on finds of such items, sometimes with runic

inscriptions from Frisia, Denmark and the Low Countries. The era is not the

same (these being late Roman Iron Age or Dark Age discoveries), nor is it

directly the same culture, but the intriguing possibility remains that the

Anglo-Saxon messenger, when arriving at the residence of our thegn who was to

prepare for war, may well have left a physical token of his visit.

The Size and

Structure of Armies

The size of the armies of Anglo-Saxon England has been a

subject of controversy for many years. It is generally thought that during the

Migration period of the fifth and sixth centuries the average size of a warband

could scarcely have numbered more than a few hundred. This much is gleaned from

the historic and archaeological evidence from what is known of the Danish late

Roman Iron Age Continental bog finds of warrior weaponry and what is drawn from

the words of renowned ancient Roman authorities such as Tacitus. As early as

the late seventh century King Ine of Wessex (688–726) was moved to categorise

numbers of armed men: ‘We call up to seven men thieves; from seven to

thirty-five a band; above that is an army.’ There is not a great deal that can

be deduced from this code, however. Ine’s army was in fact a here. It is

probably the case that fyrds and heres of the eighth century were no larger

than an extended warband, perhaps numbering just a few hundred. Not until the

later Anglo-Saxon period do things take on a quantifiable dimension, if only to

confound us with the probability that we are only ever looking at an inherent

manpower capability of a kingdom that probably never put all its available men

in the field at any one time. Except, that is, for the post-reform period of

Alfred’s reign.

A good example is the document known as the Burghal Hidage.

Datable probably to the tenth century, it gives specific garrison strengths for

thirty-three strongholds built across Alfred’s Wessex and parts of Mercia. It

even gives a formula for calculating the garrisons in term of the length of

fort’s walls and the numbers of hides providing men to garrison them. The

upshot of all this is that across his kingdom Alfred had a burghal garrison

strength of around 27,000 men. The figure for all the land south of the Thames

was probably larger in reality because the Burghal Hidage does not list the

obviously cooperative Kentish strongholds such as Canterbury and Rochester, nor

does it cover Cornwall. Moreover, Alfred’s kingdom of the Anglo-Saxons expanded

into Danish Mercia during the tenth century to become the Kingdom of the

English under Edward the Elder (900–24) and Athelstan (924–39). By the time of

King Edgar (959–75), whose kingdom stretched from the south coast to the

borders of Scotland, it must surely be the case that the king and his regional

ealdormen were capable of raising forces in the field whose numbers were at the

very lowest in their thousands.

Writing about the famous events in London in 1016, the

German Bishop Thietmar of Merseburg claims he heard there were 24,000 ‘byrnies’

(mailcoats) in London. Even he thought this was incredible, so it is unlikely

to be a casual exaggeration. Quite what has happened to all these mailcoats is

a matter only for speculation. But the most obvious place to go if we want to

make a guess at the near un-guessable, is to look at the Domesday Book and

throw around a few figures. Judging from what we have shown so far about the

apportionment of land and its division into hides, we might note that the

Domesday Book records a total of 80,000 plough teams in the kingdom of England.

The duty imposed by Æthelred II (979–1016) in 1008 requiring a ship from every

300 hides and a helmet and byrnie from every 8 hides would indicate on the face

of it a ‘royal’ navy of 267 ships and an army comprising around 10,000

mail-clad warriors. Add to these armoured men their lesser armoured retainers

at a ratio of say 2:1 and you have an army of 30,000 men. But even this figure

is conservative given our knowledge of the Alfredian garrison strength of

Wessex alone. Quite how many of these men took to the field at any one time

when required is another matter. The actual numbers in any one army of the

period must therefore have varied wildly.

One last observation on numbers goes to the Battle of

Hastings. Here, the English army is harder to quantify than that of the

Normans. The Norman army is well recorded and much research has been carried

out as to the likely numbers who came to England in September of 1066. These

figures, which are based on calculations relating to the number of recorded

ships, the actual available men in Normandy and William’s mercenary

contingents, in most people’s estimations amount to a force of between about

5,000 and 7,000 men. Although it is the result of educated guesswork, the

consensus has been that the division of Norman forces was probably along lines

of around 2,000 cavalry, 800 archers, 3,000 infantry, 1,000 sailors and

logistical support men.

But what of the Anglo-Saxon army at Hastings? William

apparently was told that he was likely to be swamped by English numbers when

Harold’s army arrived. The English army was led by Harold and his brothers

Leofwin and Gyrth, each with personal retinues numbering probably in their

hundreds. We cannot be sure how many Danes were in the army, although it is

suggested by William of Poitiers that these were ‘considerable’ and had been

sent by the king of Denmark to help the English. To the Danes we must add the

numbers of men gathered (or at least warned to attend the host) along the way.

While these may have taken time to join Harold’s force and get to London, there

is mention in the twelfth-century Robert Wace’s account of the regions from

which the king recruited his force. These comprised the men of London itself,

Kent, Hertford, Essex, Surrey, St Edmunds, Suffolk, Norwich, Norfolk,

Canterbury, Stamford, Bedford, Huntingdon, Northampton, York, Buckingham,

Nottingham, Lindsey, Lincoln, Salisbury, Dorset, Bath, Somerset, Gloucester,

Worcester, Hampshire and Berkshire. We cannot be sure how authentic this

evidence is, or whether each of the regions answered their call. It does not

represent the entire ‘national’ host, either, which may be why William of

Malmesbury suggested Harold’s numbers were not as high as they might have been.

However, if we assign an unlikely low figure of 200 men per place mentioned, we

come up with a force of 5,400 men before we have even added our Danes and

earl’s retinues. It is small wonder then that when William of Poitiers (borrowing

his style from the ancients) described the English army emerging from the

Wealden forest to the north of Senlac Ridge he said, ‘If an author from

antiquity had described Harold’s army, he would have said that as it passed

rivers dried up, the forests became open country. For from every part of the

country large numbers of English had gathered.’ If the numbers themselves are

difficult to pinpoint, the evidence outlined above must surely suggest that the

Anglo-Saxon military system, however allegedly archaic and obsolete by 1066,

was capable of sending a force of up to 10,000 or more men to Senlac Ridge that

October morning. We should not underestimate this capability.

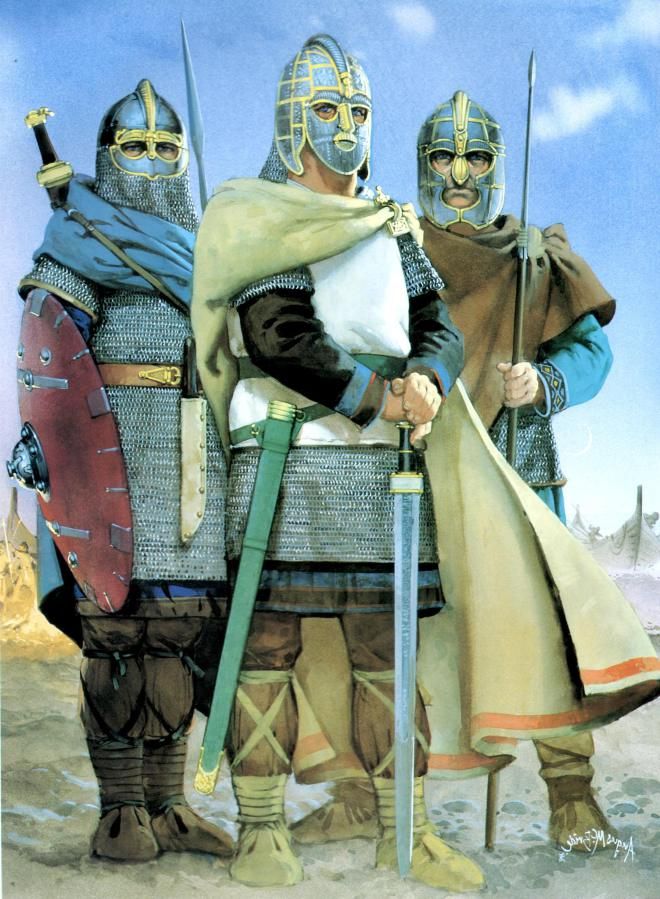

But what form did these armies take in the field? How were

they structured? At the top, of course, was the chief kinsman, the king. Around

him in the later period were the men who constituted his household retinue,

heavily armoured infantrymen. Also at the king’s disposal from the time of

Æthelred were the Danish mercenaries available as a separate subordinate

command, probably protected with mail armour and equipped with Dane-Axes.

Further still, according to Wace in his Roman de Rou, the men of London fought

around the king, presumably as heavy infantry spearmen. Wace also tells us that

it was protocol for the Kent fyrd to be the first into battle. John of

Salisbury also recalls this right of the Kent fyrd, a very prestigious right,

but he adds that after Kent, the next in order to fight would have been the men

of Wiltshire, Devon and Cornwall. The king’s close kinsmen, such as brothers

and sons (æthelings), would have their own entourages around them with the

exception of the mercenaries and Londoners. If they were all travelling

together, the size of this force alone would have been considerable. Next, the

regional ealdormen, or earls, who took their place would also form separate

command units and they would bring along with them the thegns and their men,

the ceorls, or free peasants from their estates, armed and equipped variously. These

forces were organised by shire, hundred and ‘soke’ (private holdings). It is

very clear that the armies of the later Anglo-Saxon period were both numerous

and structured.