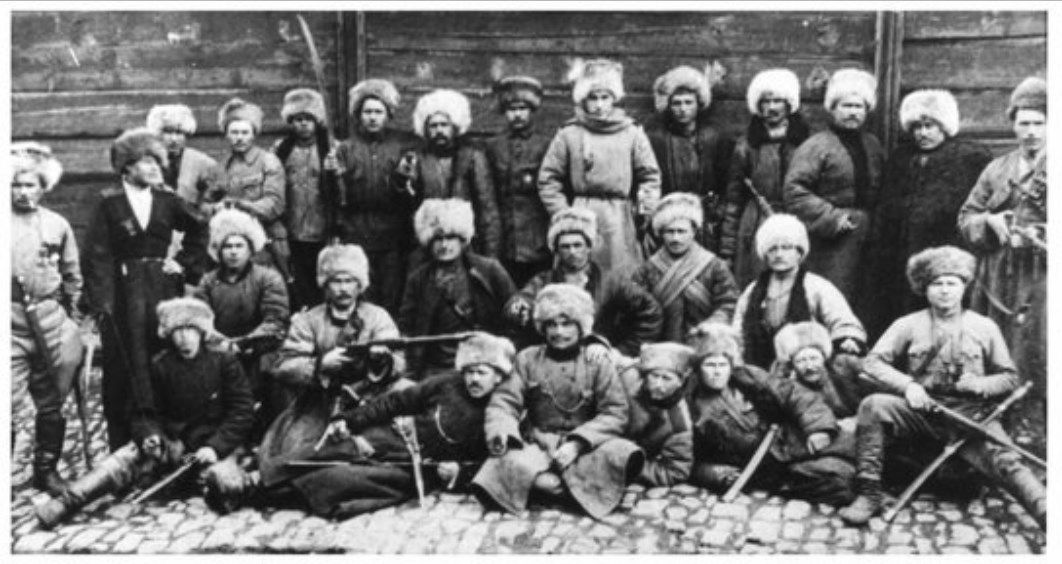

The legendary First World War and Russian Civil War partisan cavalry

unit known as ‘Shkuro’s Wolves’, pictured in 1919 during a lull in

anti-Bolshevik operations. Recruited from Kuban Cossacks, the Wolves were named

after their wolf-skin standard and papakhas (hat).

Locally recruited Basmachi guerrillas pose with their Soviet commissar

and advisor. During the 1920s elements of the native populations of the Soviet

Union’s central Asian provinces waged an unsuccessful war against their Russian

masters.

The German military had experience of partisan/guerrilla warfare from

its days as the colonial power in German East Africa (present-day Tanzania)

when local uprisings were put down with ruthless brutality. These bandsmen are

members of the German colonial forces. Indeed, a nephew of the German commander

in this region when they suffered their greatest defeat rose to become head of

Germany’s anti-bandit (partisan) warfare on the Eastern Front.

Partisan and guerrilla warfare can be loosely defined and

differentiated in the following manner. Partisan troops are those members or

affiliated members of the armed forces that are operating behind enemy lines,

whereas guerrillas are generally civilians fighting against an occupying force.

However, both terms are often used indiscriminately. In addition, the situation

is not helped by the Axis use of the umbrella term partisans only to replace it

with bandits to highlight the illegal and outlaw nature of the fighters.

In fact, partisans/guerrillas have a long and honourable

lineage in Russian and Soviet military history stretching back to the

Napoleonic Wars, when partisan units of Cossack and other mounted troops waged

war on the Grand Army’s supply lines and rear before and during the retreat

from Moscow. During the First World War partisan operations were undertaken by

Cossacks and regular cavalry, groups of which infiltrated behind German and

Austrian lines to carry out disruptive missions such as blowing up railway lines,

intelligence gathering and kidnapping. Specialist units were established in the

Cossack formations by order of the Grand Duke Boris Vladimirovitch, the Ataman

of Cossack forces at the front during 1915, but reports on their achievements

were such that the majority were disbanded. Nevertheless, some units, such as

Shkuro’s Wolves, acquitted themselves well. Following the revolution of March

1917, Russia’s armed forces began to go into gradual decline and as that

fateful year drew to a close the Bolshevik coup of November led to open civil

war that spread across the empire now turned republic. Over the next four years

partisan and guerrilla formations of all shapes, sizes and levels of

effectiveness flashed across the vastness of Russia from the mountains of the

Caucasus, across the steppes of Ukraine, the tundra and forests of Siberia to

the coastlines of the Pacific Ocean. As the Soviet government emerged from the

civil war victorious and extended its somewhat tenuous grip across the

provinces, names such as that of Chapayev became known to the public of the

USSR as one of the partisan leaders who had contributed to the destruction of

‘interventionists and counter revolutionaries’. Indeed, the lauding of partisan

leaders and groups formed almost a staple of Soviet popular culture into the

mid-1930s. Furthermore, the value of partisan warfare was seriously studied by

the higher echelons of the Soviet military.

In parallel, Soviet military theory during the 1920s and

into the 1930s included the use of partisan formations to disrupt invaders’

lines of supply, communications and reinforcement.

Plans were laid for the establishment of secret bases along

anticipated invasion routes to supply partisan groups who would train in the

use of ‘captured weapons and equipment’. Local forces would be supported by

specialists, such as radio operators and demolition experts, who would be

parachuted in. Some work and training was under taken by the Ukrainian Military

District in the years leading up to 1936. However, Stalin, increasingly

suspicious of the armed forces, was, like Hitler, a military theorist and a

firm believer in the offensive as the ultimate strategy. Furthermore, any

thoughts that a war would be fought on Soviet territory were anathema to him.

Equally unappealing was the prospect of encouraging and arming elements of the

populace in the very areas where famine, disease and starvation stalked the

land in the wake of his disastrous agricultural policy of forced

collectivisation. Training such victims in the ways of partisan and guerilla

warfare was not to be encouraged. Consequently, as the infamous purges of the

armed forces decimated the officer corps, thoughts of any war waged on Soviet

land was replaced by offensive operations beyond the frontiers and the partisan

bases already built were allowed to revert to their natural condition whilst

the plans mouldered on shelves in the archives. Another major aspect of

partisan warfare that Stalin wished actively to eliminate was the very set of

characteristics that made for effective leadership in partisan groups: the

ability to think and plan independently beyond the control of Moscow; the

capacity to adapt to local circumstances as required; and the charisma to hold

together such a group in times of danger and low morale. Lumped together, these

characteristics were known disparagingly as Partisanshchina–a trait not to be

encouraged in a totalitarian regime.

It was the shock of the Axis invasion that would regenerate

the need for partisan warfare on a scale unimaginable only a few years before

as the people, not only the armed forces, would be called upon to fight a

ruthless invader.

Minsk race course witnessed the partisans’ grand parade on 17 July

1944. As one participant recalled, ‘They were met with enthusiasm, they marched

proudly with medals on (their) chests! They were the winners!’ Dozens of

units were represented and hundreds of fighters marched past the podium where

Ponomarenko took the salute alongside other Party luminaries. The final order

to the partisans was to, ‘start preparations for (their) disbandment.

Often overlooked, due to the scale of partisan operations

behind AGC, the partisan formations to the rear of AGN were to take centre

stage as 1944 dawned. During 1942 there had been little activity in the north

but the Leningrad Partisan HQ had worked hard to increase the number and

efficiency of the units it oversaw. Consolidation of small bands into larger

ones and a ruthless review of the qualities of the leaders resulted, by the

summer of 1943, in a considerably more effective force. As the area under the

control of the LPHQ was smaller than that of, for example, Belarus communications,

control and co-ordination were simpler. By the end of 1943 10 partisan

brigades, numbering ‘35,000 active fighters and thousands of auxiliaries’ were

in place. During October 1943 Fifth Partisan Brigade captured the town of

Plijusa on the Luga–Pskov rail line to prevent the deportation of the civilian

population. This action was replicated by other formations across the rear of

AGN. Indeed, it was the groundswell of popular disaffection that was to lead to

Hitler’s decision to withdraw to the Panther Line when the Red Army offensive

was gaining momentum four months later.

The Soviets intended to drive AGN away from the Leningrad

district into the Baltic States and began their attack on 14 January 1944.

Partisan attacks did not begin until virtually all the security troops had been

committed to the front line. It was on the evening of 16 January that the

partisans began to interfere with the railways by destroying Tolmachevo

station. The following night a more general series of attacks on security posts

and the track itself were carried out. By 20 January the railway situation was

described as ‘tense’ and in some areas as ‘completely paralysed’. Supply and

troop transports ground to a halt as partisan attacks increased ‘tremendously’.

The 8th Jaeger Division took four days to move and then only partially into

position, three days later than anticipated due to the mining of both road and

railway. As the Germans withdrew, NKVD personnel were parachuted into Estonia

and Latvia to organise partisan groups. By mid-February the Eighth Leningrad

Partisan Brigade was identified heading for Latvia. Active measures by the

HSSPF Ostland had drafted thousands of Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian Schuma

troops to deal with this threat–they succeeded, intercepting the partisans in a

series of running fights. The majority of the partisans from the Leningrad

region had been enrolled in the Red Army but the surviving infiltrators behind

AGN confined their activities to propaganda and intelligence work due to the

general antipathy of the locals to the prospect of Soviet liberation.

Far to the south in Ukraine Medvedev and Kovpak’s units

still continued their combat and propaganda missions. The Chief of Staff of the

Ukrainian Partisan Movement, Colonel General Strokach, was, by late 1943,

closely connected with the regular army and expanding his role to look beyond

the borders of the USSR. Rather than just sending partisan units behind Axis

lines, where the fighting with nationalists was increasing and with much of

Ukraine back under Soviet control, Strokach’s staff began to train pro-Soviet

partisans for operations in Poland and Czechoslovakia. Whatever motives were

announced for these activities during the winter of 1943–1944, the long-term

aim was to lay the foundations for future Communist regimes in those countries.

Czechoslovakia, of which only Slovakia nominally existed, and Poland both had

governments in exile in Britain, of which Stalin fundamentally disapproved.

However, both had partisan movements and those of Poland were mainly

anti-Soviet. The Polish Home Army (the AK) was a large, active and

well-organised force that operated in both German and Soviet-claimed Poland.

The AK wanted a return to Poland’s pre-1939 frontiers which effectively put it

at odds with the USSR’s claims to western Ukraine and Belarus. The Ukrainian

Partisan Staff was, therefore, to bend its efforts to create a pro-Soviet,

Communist partisan force to match the AK in those areas. By January 1944 the

Red Army had crossed into pre-war Polish territory into land Moscow coveted.

The Polish government in exile had ordered the AK to support Soviet operations,

but Polish partisans could not be mobilised into the Soviet-sponsored Polish

Army. In western Ukraine and Galicia NKVD partisan units, such as those of

Medvedev, and those organised by Strokach operated regardless of international

boundaries. When a frontier was crossed the unit commander would open his

sealed orders that generally read that he should ‘act according to the existing

conditions’. Fighting promptly broke out with the AK when the Soviets began to

bring the tiny GL (Guardija Ludowa) into play. The GL was a Polish Communist

Party partisan group. Members of the GL were flown to a Ukrainian Partisan

Staff’s training camp where they had prepared for operations in Poland. In

April 1944 the Polish Staff for the Partisan Movement was set up in Rovno,

overseen by Strokach, to control the GL units that were now operating against

the Germans, the AK and the Ukrainian nationalists. At the same time the

Czechoslovak Communist Party appealed to Moscow for help in waging a partisan

war. Once again a training cadre was taken in by Strokach’s staff. During the

spring and summer of 1944 bases were established, particularly in Slovakia, and

covert recruitment of local partisans began. Their situation was helped by the

Red Air Force that flew in supplies almost at will due to the Luftwaffe’s

weakness over Eastern Europe.

Finally, on 28 August 1944 the Slovaks rose up against their

pro-Nazi government, but the country was, during the course of the next week,

overrun by a motley collection of German troops. A Soviet attempt to alleviate

the situation, by elements of First Ukrainian Front battling its way through

the Carpathian Mountains, failed. By the end of October the Slovakian Uprising

was over, but, nevertheless, some stragglers fought on in the mountains. The

Soviet effort in Slovakia was certainly greater than that made to support the

Warsaw Uprising of August 1944. When that tragic event ended in the defeat of

the AK there were many stragglers who made their way east. With the AK

apparently a broken force, Stalin directed the NKVD to round-up any units found

in Soviet territory. Interestingly, such partisans were referred to in NKVD

reports as, ‘illegal formations, rebels or bandits’. Indeed, round-ups of AK

fighters had been going on for months prior to the Warsaw Uprising. One unit,

answering the call to go to Warsaw in July to reinforce the forthcoming

uprising, had arrived east of the city at the same time as the Red Army. Having

liberated several villages in the wake of the retreating Germans, they suddenly

radioed a message, un-coded, that was intercepted in Britain, ‘they [Red Army]

are approaching us . . . they are disarming us’. The foundations were being

laid for the Soviet liberation of Poland.

For the Soviet partisans the stage for its most impressive

operation had been set several months before. During the winter of 1943–1944

the Soviet fronts facing AGC had been relatively quiet. Hitler, convinced that

the next series of Soviet offensives would continue to push against AGS, had

split that front into two, Army Group South Ukraine (AGSU) and Army Group North

Ukraine (AGNU). The latter was expected to be the target and, therefore, was

the strongest in terms of armour. The southern flank of AGC ran south-west from

Bobruisk just below the Pripet Marshes to a point west of Lutsk and the AGNU

and AGSU took over with fronts that sloped eastwards to the Black Sea west of

Odessa.

From the spring of 1944 onwards Moscow had received a stream

of intelligence reports that detailed AGC’s order of battle and defensive

preparations. More and more partisan and NKVD intelligence-gathering operations

were carried out. Before this the NKVD had tended to act alone due to a lack of

trust in partisans other than their own units. The reason for this was simple:

the NKVD was afraid of its agents falling into the hands of German-run ‘mock

partisan’ bands who operated in the hope of flushing out the real thing and

bandit sympathisers. However, the orders under which the partisans now operated

did not come from the CHQPM, as that body had been wound up on 13 January 1944.

The responsibility for the partisans now rested with the

Communist Party of the appropriate republic and its local regional hierarchy.

The partisans were directed, by the Belorussian Communist Party’s Central

Committee, to cease operations behind AGC to encourage the Germans to reinforce

their belief that the offensive was aimed at AGNU. Then, on 20 June, they unleashed

another Operation Rail War. This time the targets were the one heavy capacity,

double-tracked line and the five lower capacity lines on which AGC depended.

The few-surviving German records are slim but indicate almost two-thirds of the

4,000 demolition attempts succeeded, ‘the lines Minsk–Orsha and Mogilev–Vitebsk

were especially hard hit and almost completely paralysed for several days’. The

Soviets calculated that ‘the partisan bands blew up 40,000 rails and derailed

147 trains’. Roads were mined and convoys attacked.

Operation Bagration burst across the lines of AGC in a

series of waves from 22 June 1944, three years to the day after Operation

Barbarossa had provoked the Great Patriotic War, as the Soviets termed it.

However, as the Red Army advanced up to 50km per day, AGC began to collapse,

the partisans came out into the open. Several units had been ordered to ambush

and mount delaying attacks on retreating German forces and to try and secure

river crossings. The latter efforts were generally unsuccessful but the former

were not. As German units, escaping from cities such as Vitebsk, disintegrated

under air and artillery fire, the partisans, eager for revenge, struck. With no

facilities for and probably less inclination to take prisoners, the partisans,

their numbers augmented by any civilians inclined to pick up a gun, wreaked a

fearful toll. No figures are available but it is estimated that up to 20,000

German troops died trying to escape from the Vitebsk encirclement. Similar

episodes occurred throughout Belarus during the last week of June and into

July. Within a week the Red Army had reached and crossed the Berezina River and

on 3 July entered Minsk, capital of Belarus. AGC had dissolved in less than a

month.

Across Belarus thousands of partisans were drafted into the

regular army, whilst others took the opportunity to go ‘Fritz hunting’

alongside special army units tasked with flushing out German stragglers, of

which there were thousands wandering amidst the marshes and forests.

The partisan parade in Minsk effectively signalled the end

of the ‘amateur’ partisan.

Now it was the time for the NKVD, the ‘professionals’, such

as Vershigora’s 1st Ukrainian Partisan Division, to head west to continue with

their old and new tasks. A partisan medal, in two classes, was struck and

issued liberally. In the Baltic States and Ukraine nationalist partisans fought

on against Soviet rule for over a decade. Simultaneously, the Soviet partisan

movement rapidly became enshrined in many, somewhat embellished, official histories,

films and other media forms.

Whilst there is no doubting the vileness of German rule in

the occupied territories, there are grounds for doubting some of the tales of

the partisans’ achievements, but such histories are always written by the victors.

Nevertheless, for the ordinary men and women who lived and fought against the

invader it was a time in their lives of which they have every right to be

justly proud. There is no doubt that they made a definite contribution to the

victory over the Third Reich by their very defiance.