Sumerian

1. Muriq Tidnim (conjectural)

Babylonian Line 1

2. Nebuchadnezzar’s Babylon to Kish Wall (conjectural)

Babylonian Line 2

3. Habl es-Sakhar (Nebuchadnezzar’s Sippar to Opis Wall,

Median Wall)

Line 3 (uncertain)

4. El-Mutabbaq

5. Sadd Nimrud (also called El-Jalu)

6. Umm Raus Wall (site of Macepracta Wall(?), Artaxerxes’

Trench(?))

Sasanian

Khandaq-i-Shapur

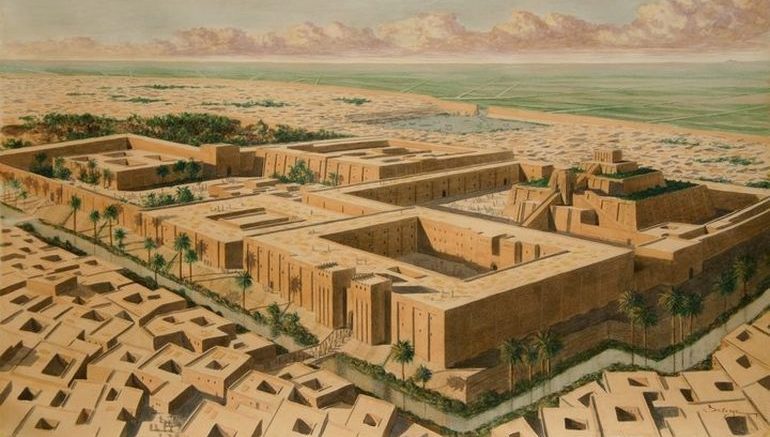

Mesopotamia and the

Rivers Tigris and the Euphrates

Egypt shows that the conjunction of irrigated lands and

nomads produced linear barriers – even if the evidence might seem elusive and

inconclusive. Therefore, might also then Mesopotamia, with the similarly

intensely irrigated Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, produce evidence of walls in

the presence of nomads?

In Mesopotamia, the area of irrigated lands runs along the

flood plains of the Tigris and the Euphrates up to, and somewhat beyond, the

convergence points of the rivers between ancient Babylon and modern Baghdad.

Above that point the alluvial plain peters out and the land becomes too hilly

to allow for intense irrigation. From the north-east flows the Diyala River

which passes through the Zagros Mountains to join the Tigris, linking the high

Persian plateau to Mesopotamia. Around the river was especially valued

irrigated land. The area of convergence of the Tigris and Euphrates constituted

a constricted land corridor. Local nomads and semi-nomads would have been

expected to press particularly hard on the rich and productive irrigated lands

of Mesopotamia.

As in Egypt, civilisation, sustained by the irrigated lands

of Mesopotamia, came early, in the fourth millennia BC, with the Sumerians.

Again, as with Egypt, there is evidence of climate change. In the last century

of the third millennium BC the stream flow of the Euphrates and the Tigris was

very low, according to analysis of sediments in the Persian Gulf. The end of

the Akkadian era, due to defeat by the hated Gutian peoples from the

mountainous east in the twenty-second century BC, coincided with a few decades

of intense drought which was followed by two to three centuries of dry weather.

Ur revived and under Ur-Nammu defeated the Gutians and established the third

dynasty of Ur, commonly abbreviated to Ur III, in 2112 BC. The Sumerians

initiated a short period of cultural renaissance in a time of constant conflict

with the semi-nomadic Martu – more familiar as the biblical Amorites.

Indeed, Ur III may have faced two reasonably distinct

threats. From the north-west there was the Martu whose aim may in part have

been to gain sustenance for their herds in times of drought. The direction of

the threat that they posed would have been through the relatively flat lands

between and to both sides of the convergence point of the Euphrates and the

Tigris. To the north-east were the Elamites and Shimashki confederation in the

highlands to the east of the Tigris. Their lines of attack would have been more

focused down river valleys – perhaps the Diyala River flowing through the

Zagros Mountains to the Tigris.

Mesopotamian linear

barriers

In this early period there is only textual evidence for

linear barriers, based on letters that remarkably survive from the third

dynasty of Ur. These writings between Sumerian kings and their often

disobedient generals and officials, are called the Royal Correspondence of Ur

(abbreviated to the RCU). Much of the correspondence in the twenty-two or so

surviving letters was about defence against the Martu. There was also

information about linear barriers in the year names of Sumerian king lists

(Mesopotamian kings named each year of their reigns after some major event).

The Sumerian kings

Shulgi (2094–2047 BC), Shu-Sin (2037–2029 BC) and Ibbi-Sin (2028–2004 BC) were

mentioned in the context of three walls:

bad-mada/Wall of the Land – The Wall of the Land is known

only from one reference in the king lists: ‘Year 37: Nanna (the god) and Shulgi

the king built the Wall of the land.’10 Shulgi was on the throne for

forty-seven years so the wall belongs to the last quarter of his long reign.

This was a time of increasing pressure on central and southern Mesopotamia from

the Martu.

bad-igi-hur-sag-ga/Wall Facing the Highlands – In the RCU

there are several references to bad-igi-hur-sag-ga – both during Shulgi’s reign

and that of his successors, Shu-Sin and Ibbi-Sin. The bad-igi-hur-sag-ga has

been variously translated as the Wall, Fortress, or the Fortification facing

the highlands or mountains – making it uncertain whether this was a continuous

linear barrier. If, however, Shulgi really did build a long wall then he has

the distinction of being the first known builder of such a barrier. This

obstacle possibly faced a threat coming down the Diyala River as it faced the

Highlands, presumably the Zagros Mountains.

Muriq Tidnim/Fender off of the Tidnim – There are three

references to Muriq Tidnim, or fender (off) of the Tidnim and Shu-Sin. First,

the king lists of his fourth regnal year said: ‘Shu-Sin the king of Ur built

the amurru (Amorite) wall (called) ‘Muriq Tidnim/holding back the Tidanum’’

Second, there is an inscription in a temple built for the god Shara: ‘For Shara

Shu-Sin built the Eshagepada, his (Shara’s) beloved temple, for his (Shu-Sin’s)

life when he built the Martu wall Muriq Tidnim (and) turned back the paths of

the Martu to their land.’ Third, the most informative reference to the Muriq

Tidnim is in a letter from Sharrum-bani, an official of Shu-Sin. ‘You sent me a

message ordering me to work on the construction of the great fortification

Muriq Tidnim … announcing: “The Martu have invaded the land.” You instructed me

to build the fortification, so as to cut off their route; also, that no

breaches of the Tigris or the Euphrates should cover the fields with water …

from the bank of the Ab-gal watercourse to the province of Zimudar. When I was

constructing this fortification to the length of 26 danna, and had reached the

area between the two mountain ranges, I was informed of the Martu camping

within the mountain ranges because of my building work.’

In this letter, the construction is described as ‘great’.

Whatever the uncertainties about Shulgi’s earlier edifices, it is difficult not

to interpret this passage as describing a major continuous linear barrier. In

the west the Ab-gal canal is associated with an earlier western course of the

Euphrates and to the east the province of Zimudar is identified as being on the

east side of Tigris in the region of the Diyala river. A danna is about two

hours march so 26 dannas may be over 150 kilometres. Therefore, the edifice

appeared to extend from the Euphrates to the other side of the Tigris because

its length was much greater than the distance between the two rivers. The

instructions to build the walls specifically cite stopping the semi-nomadic

Martu from overwhelming the fields by a breach between the Tigris and the

Euphrates, showing that irrigated land was perceived as particularly

vulnerable.

Analysis – Ur III

In the hillier east controlling access down the Diyala river

area there may have been a single fortification, the bad-igi-hur-sag-ga or the

Wall/Fortress facing the Highlands, first built by Shulgi, which might or might

not have been part of another system bad-mada (the Wall of the Land) built in

the flatter west. During the reign of Shu-Sin it seems more likely that a linear

barrier called Muriq Tidnim was built from new, or it consisted of earlier

lines that were linked and much reinforced including Shulgi’s Wall of the land.

This is all speculation but there is good if circumstantial literary evidence

that Ur III’s strategy for defence against the Martu involved the construction

of what would be the first recorded long continuous non-aquatic linear

barriers.

There does seem to be a fairly general academic acceptance

that under Shulgi and Shu-Sin long walls were built and their purpose was to

keep out nomads. For example: ‘Even as early as year 35 of Shulgi, the (nomad)

problem was becoming so grave that Shulgi constructed a wall to keep them

(pastoral and semi-nomadic Amorites) out, and Shu-Sin built another barrier,

called “fender off of Tidnim,” 200 kilometres long, stretching between the

Tigris and the Euphrates across the northern edge of the alluvial plain.’ Also:

‘Yet despite Shulgi’s talents, within a few years of his death in 2047 BC his

Empire, too, imploded. In the 2030s raiding became such a problem that Ur built

a hundred-mile wall to keep the Amorites out.’

Later Mesopotamia

Looking at later Mesopotamia, after the fall of Ur III, how

did it defend itself in times of necessity? What emerges is three intense periods

of barrier building: firstly, that already discussed, during the short lived Ur

III period; secondly, in the neo-Babylonian period associated with

Nebuchadnezzar in the sixth century BC; and thirdly, later in the fourth

century, aquatic linear barriers were built by the Sasanians. There are also a

number of major but little studied walls, discussed below, north of the Tigris

and Euphrates convergence point, which are not clearly dated.

After Ur III fell to the Elamites and the Shimaskhi

confederation, the so-called Amorite dynasty of Isin completed its breakaway.

Given that lower Mesopotamia had fallen to peoples from outside the region

there was no reason for a barrier between the north and southern Mesopotamia.

Also, Martu or Amorite semi-nomads were becoming increasingly sedentarised.

Subsequently, the Babylonians of the era of Hammurabi were able to project

their power well to the north of Babylon. The Assyrians, coming from the north,

had no need for walls around 700 BC to defend Babylon in this region as they

controlled the regions to its north and south.

The neo-Babylonians recovered control of their city in the

sixth century BC and made it the capital of the region. The second period of

major barrier building materialised in this later Babylonian period, associated

with Nebuchadnezzar and textually with Queens Semiramis and Nitocris.

Nebuchadnezzar II ruled for forty-three years from 604 to 562 BC. The Medes’

conquest of Lydia made Nebuchadnezzar suspicious of their intentions and this

led him to strengthen his northern border. Behind the Medes loomed the

Persians. This was clearly seen, rightly as it turned out, as a real,

unpredictable threat – and one that prompted the construction of a

comprehensive linear barrier system. Notwithstanding this attempt, in 539 BC

Cyrus the Great led the Medes and the Persians into Babylonia which was

absorbed into the Achaemenid Empire.

Linear barriers –

survey

There were three lines of barriers at and above Babylon

looked at here, starting in the south and going to the north.

Babylon to Kish –

Line 1

Two walls of Nebuchadnezzar (604–562 BC) are known from a

clay cylinder, dated to 590 BC when relations between the Babylonians and the

Medes had deteriorated. (These compose Line 1 and Line 2 in this and the next

section.)

Nebuchadnezzar’s Wall from near Babylon to Kish – This

cylinder is inscribed: ‘In the district of Babylon from the chau(s)sée on the

Euphrates bank to Kish, 4 2/3 bēru long, I heaped up on the level of the ground

an earth-wall and surrounded the City with mighty waters. That no crack should

appear in it, I plastered its slope with asphalt and bricks.’ A bēru is the

distance which could be travelled in two hours so is variable according to

terrain. At five kilometres an hour this barrier would be about 47 kilometres

long. The problem is that this is considerably longer than the distance between

Babylon and Kish – which is little more than 10 kilometres – unless the barrier

followed a particularly circuitous route. Also, it would seem a fairly

pointless military exercise building a barrier from Babylon to Kish leaving the

flood plain open to the east from Kish to the Tigris. Using up the surplus kilometres

would take the wall further east to Kar-Nargal, near an earlier channel of the

Tigris, hence blocking the land corridor between the Euphrates and the Tigris.

No physical evidence of this wall has been identified.

Opis to Sippar – Line

2

The second line ran between the cities of Sippar, above

Babylon on the Euphrates, and Opis on the Tigris, the precise position of which

has been lost. A number of walls are associated with this location in texts and

there is a surviving wall called Habl-es-Sakhar.

Nebuchadnezzar’s Wall from Sippar to Opis – Nebuchadnezzar’s

inscribed cylinder described the second wall as follows: ‘To strengthen the

fortification of Babylon, I continued, and from Opis upstream to the middle of

Sippar, from Tigris bank to Euphrates bank, 5 bēru, I heaped up a mighty

earth-wall and surrounded the city for 20 bēru like the fullness of the sea.

That the pressure of the water should not harm the dike, I plastered its slope

with asphalt and bricks.’ This Opis to Sippar wall would have been about 50

kilometres long. Both the Babylon to Kish and the Opis to Sippar walls were

water-proofed by asphalt so they must have been built in proximity to water –

possibly water-courses like canals or in flatlands prone to flooding or

swamping.

Wall of Semiramis – The geographer Strabo, citing

Eratosthenes, when describing Mesopotamia, said the Tigris, ‘goes to Opis, and

to the wall of Semiramis, as it is called.’ Therefore, this wall was in the

region of the Tigris and the Euphrates’ convergence point. (Herodotus mentioned

Semiramis’ works but did not specify a wall. Rather he described levees which

controlled flooding.)

Wall of Nitrocris – Herodotus also described a Babylonian

queen called Nitocris – possibly the daughter of Nebuchadnezzar and the mother of

the Book of Daniel’s King Belshazzar brought down by Cyrus – whose

constructions in Babylon were mainly connected with diverting the Euphrates.

Nitocris built works in the entrance of the country (which is clearly a

description of a land corridor) against the threat of the Medes. ‘Nitocris …

observing the great power and restless enterprise of the Medes, … and expecting

to be attacked in her turn, made all possible exertions to increase the

defences of her empire.’

Wall of Media – In the Anabasis, Xenophon described how he

led the 10,000 Greeks back from Mesopotamia. In it he encountered the Wall of

Media twice. Here what is described is the second occasion when Xenophon

actually crossed the wall itself following the battle of Cunaxa in 401 BC.

‘They reached the so called Wall of Media and passed within it. It was built of

baked bricks, laid in asphalt, and was twenty feet wide and a hundred feet

high; its length was said to be twenty parasangs, and it is not far distant

from Babylon.’ Assuming that a parasang is the same as a bēru or a danna, that

is a two hours march, then the wall was about 100 kilometres long.

Habl-es-Sakhar – There is a surviving wall in the vicinity

of Sippar. In 1867 one Captain Bewsher described the ruins of a wall then

called Habl-es-Sakhar – which translates from the Arabic as a line of stones or

bricks. ‘The ruins of this wall may now be traced for about 10½ miles and are

about 6 feet above the level of the soil. It was irregularly built, the longest

side running E.S.E. for 5½ miles; it then turns to N.N.E. for another mile and

a half. An extensive swamp to the northward has done much towards reducing the

wall.… There is a considerable quantity of bitumen scattered about, and it was

probably made of bricks set in bitumen. I can see nothing in Xenophon which

would show this was not the wall the Greeks passed, for what he says of its

length was merely what was told him.’ The description of the ‘baked bricks laid

upon bitumen’ is like Nebuchadnezzar’s description of his wall between Opis and

Sippar: plastered with asphalt and bricks.

In 1983 a joint team of Belgian and British Archaeological

Expeditions to Iraq investigated the ruins of Habl-es-Sakhar. This confirmed

that Habl-es-Sakhar was built by Nebuchadnezzar, for bricks marked with his

name were found during its excavation. The team reported that Habl-es-Sakhar is

the name of ‘a levee 30 metres wide and 1 metre high which could be followed

for about 15 kilometres. A trench across the levee to the north of the site of

Sippar revealed baked brick walls (largely robbed) on either side of an earth

embankment. The earth core was about 3.2m wide and the brick walls about 1.75m

in width. Between the brick courses was a skin of bitumen. On the bottom of

each brick was a stamp of Nebuchadnezzar. If the wall extended to the ancient

line of the Tigris it would have been nearly 40k long.’

The wall stood astride the northern approaches to Babylon

itself. The wall’s function appeared primarily to have been military as it was

not well situated to protect land against the flooding of the Euphrates which

lay to the south. It is ‘beyond reasonable doubt’ that Habl-es-Sakhar is

Nebuchadnezzar’s wall and Xenophon’s Wall of Media due to the location north of

Sippar, the details of the construction, and the stamped bricks set in bitumen.

This is rather satisfying because a surviving wall has been matched up with

literary text.

Umm Raus to Samarra –

Line 3

A third line of walls runs from Samarra on the Tigris to

Ramadi on the Euphrates which delineated the upper limits of the alluvial plain

where intense irrigation was possible. Here the fertile plain is not continuous

between the Tigris and the Euphrates but the regions close to the rivers fit

the description of valued irrigated land. As the rivers have diverged already

significantly in the area of the third uppermost line, compared to the lower

two lines, a wall that extended the whole distance would have had to have been

much longer. Central sections might also have been purposeless as there was little

valued, highly irrigated, land to protect and attackers would not have wanted

to stray too far into less fertile land. This area is the site of two walls

described in ancient texts and three surviving linear barriers.

Trench of Artaxerxes – In the Anabasis Xenophon described

the march along the Euphrates, at the point where canals began, thereby

indicating intense irrigation: ‘Cyrus … expected the king to give battle the

same day, for in the middle of this day’s march a deep sunk trench was reached,

thirty feet broad, and eighteen feet deep.… The trench itself had been

constructed by the great king upon hearing of Cyrus’s approach, to serve as a

line of defence.’ The trench does not appear to have survived but the site

might have been reused to build later walls – the first being the Wall of

Macepracta, discussed next, and second the surviving wall at Umm Raus.

Wall of Macepracta – Ammianus Marcellinus, describing the

assault in AD 362 by the apostate Emperor Julian on the Sasasian Empire of

Shapur II, wrote: ‘our soldiers came to the village of Macepracta, where the

half-destroyed traces of walls were seen; these in early times had a wide

extent, it was said, and protected Assyria from hostile inroads.’

There is a surviving belt of linear barriers which extends –

with long gaps – between the Euphrates and the Tigris. The three walls mark the

line where the fertile Babylonian plain peters out. There is the rampart

starting at Umm-Raus which extends east from the Euphrates; El-Mutabbaq is a

burnt brick wall with towers running west from the Tigris; and between them is

a dyke named Sadd Nimrud (also called El-Jalu). Their dating is very uncertain.

Wall at Umm Raus – The wall, running east from the

Euphrates, has been described: ‘From Umm Raus we see the wall running inland

for a distance of about 7 miles, with rounded bastions at intervals for 2½

miles.… The wall appeared to be about 35–45 ft broad, with bastions projecting

about 20ft. to 25ft., set at a distance of about 190 feet axis to axis. At its

highest point the mound made by the wall is about 7 to 8 feet high. From the

air it can be seen that there are about forty buttresses in all.’

The line may follow that of Artaxerxes’ trench. It is not a

brick wall but an earth rampart. It was ‘never defensible, perhaps never

finished’. Also: ‘This wall must have been designed … to protect the suddenly

broadening area of fertile irrigated land to its south from raids and

infiltration; large armies entering Iraq by the Euphrates would not have found

it a serious obstacle.’

Again, there is the explicit mention of defending irrigated

land. The Umm Raus rampart must date between 401 BC, as it is not mentioned by

Xenophon, and AD 363, when a ruined wall was described at Macepracta by

Ammianus Marcellinus.

El-Mutabbaq – The modern name, El-Mutabbaq, means built in

layers or courses of bricks. This is a massive rampart lying at the boundary of

the irrigatel alluvium of the widening Tigris valley south of Samarra and the

desert to the north-west. It is about forty kilometres long and ‘has traces of

turrets and moat on the north-west side and follows … the natural contours of

the land. The rampart was four to six metres high, thirty metres wide at the

bottom.’ It is, ‘a mud-brick wall three and a half bricks wide behind which is

10.5m of gravel-packing held in by a small mud-wall. The gravel packing was

compartmented by mud-brick cross walls. There are projecting towers at regular

intervals and a ditch about 20 to 30m. wide which is now about 2m. deep.’

The following description shows El-Mutabbaq as being

designed to protect valued land against a nomad threat: ‘Herzfeld (a German

explorer and historian) attributed construction to the threat of the Bedouin

invading the fertile area along the Tigris by the river Dujail.’ These walls

were seen as intended to stop nomads thereby affirming their ineffectiveness

against great armies: ‘Cross-country walls of this type are notoriously

inefficient at stopping great armies; this particular example could be

outflanked without any difficulty at all. A stronger objection to any theory

that it was designed to stop a great army is that it blocks the one route into

southern Mesopotamia which, because of natural obstacles north of Samarra,

invading armies have preferred never to use.’ The walls were intended to defend

irrigated land: ‘El-Mutabbaq was more probably intended to help protect the

irrigated land from unwanted settlers and raiding parties coming from the

desert.’ There is no consensus as to the builder although they are described as

Sasanian. Basically, these linear barriers do not seem to have been examined

since the 1960s and remain effectively undated.

Sadd Nimrud – A dyke called Sadd Nimrud or El-Jalu, which is

about forty kilometres long, that lies to the west of El-Muttabaq. This linear

barrier does not extend the full distance between El-Muttabaq and the Wall at

Umm Raus: ‘The fortification in the central area peters out in the direction of

Falluja – perhaps as a considerable gap did not need to be defended – as armies

could not advance far into the desert away from water.’ No date, other than

this possibly being pre-Islamic, has been suggested.

Analysis – three

lines at the Euphrates and Tigris convergence point

These three barriers between the Tigris and the Euphrates

present a very baffling picture. They follow roughly the line where intense

irrigation ceases. Rather than being a single response, however, they seem to

be three discrete AD hoc reactions to separate threats to irrigated lands near

the rivers Tigris and Euphrates. They can lay claim to being among the longest

and oldest walls outside China, excepting certain Roman and Sasanian walls, yet

there appears to have been no very detailed study of them. The attribution is

generally vague – with comparisons made to features on Sumerian to Sasanian

walls, in other words millennia apart. Generally commentators do regard them as

forming part of a local response to the need to protect valued irrigated land

in the immediate vicinity, rather than as having any strategic purpose to block

routes into central and southern Mesopotamia.

Sasanian aquatic

barriers

In the early fourth century AD a semi-nomadic people, the

Lakhmid Arabs, who were originally from the Yemen, emerged as a serious threat

to Sasanian Mesopotamia.

Khandaq-i-Shapur – Arab tradition associates Shapur II (AD

309–379) with a defensive dyke that reputedly ran west of the Euphrates, from

Hit to Basra. This barrier is looked at again later when Sasanian barriers are

discussed. It is clear however that the linear barrier was built to hinder the

nomadic Arab people from the desert. Although this Khandaq is much later than

the Egyptian Walls of the Ruler, it throws an interesting perspective on it.

Firstly, there is neat symmetry. In the face of a threat from nomadic Asiatics,

the response to both the east and the west of the Arabian Desert was to build a

moat or canal. Secondly, the historian Yāqūt, writing later in the Islamic period,

said that Anushirvan (531–579) who rebuilt Shapur’s earlier work, ‘built on it

(the moat) towers and pavilions and he joined it together with fortified

points.’ Therefore, this was a continuous fortified aquatic linear barrier. The

fact that such a barrier was constructed by the Sasanians perhaps meant that

Egypt’s early Walls of the Ruler were also a continuous aquatic barrier,

strengthened by forts.