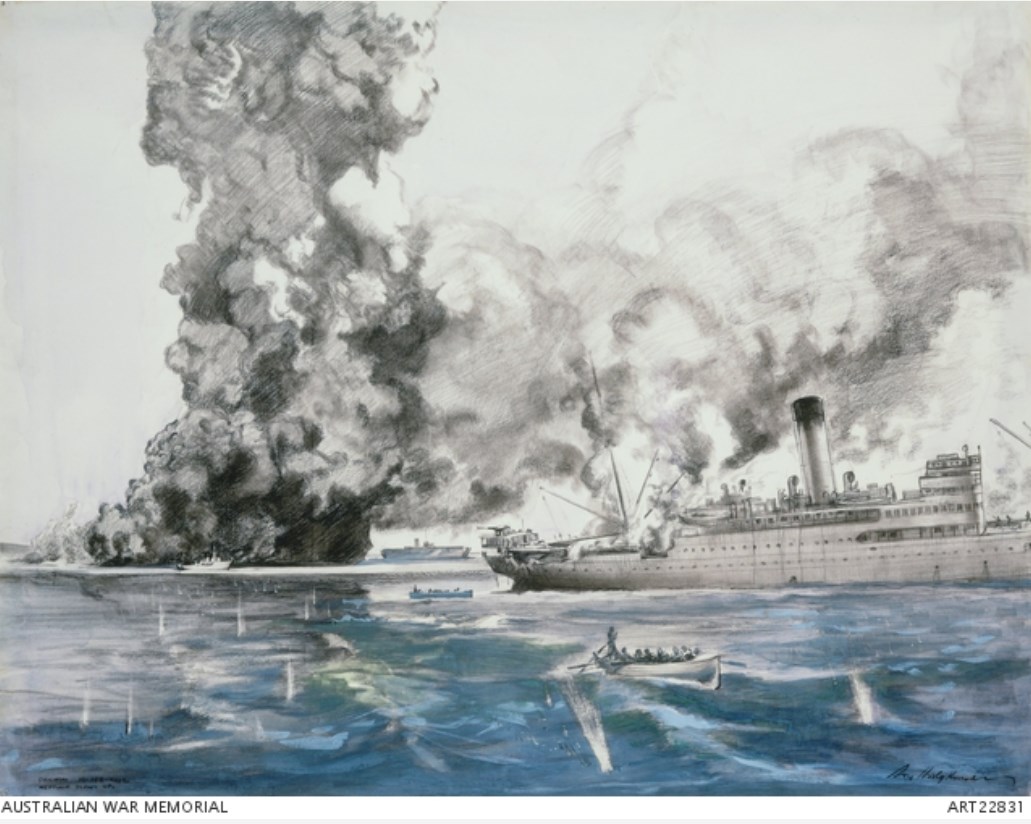

This work was drawn from a small set of photographs taken by an able seaman on a corvette on the day that the Japanese first bombed Darwin. The SS Neptuna was bombed whilst berthed at the Darwin Jetty. The ship was loaded with mixed cargo and depth charges, it caught alight and eventually blew up. Directly in front of the explosion the tiny Vigilant can be seen doing rescue work. To the right in the background is the floating dock holding the SS Katoomba which escaped the bombing. In the foreground is the SS Zealandia which was dive bombed and which eventually foundered. On that day 9 of the 13 ships in the Harbour were sunk. AWM

This historical painting is a reinterpretation of the Japanese air raid

on Darwin on 19 February 1942. Japanese aircraft fly overhead, while the focus

of the painting is the Royal Australian Navy corvette HMAS Katoomba, in dry

dock, fighting off the aerial attacks. In 1972, artist Keith Swain, approached

the Australian War Memorial with a sketch for the proposed large-scale

painting. Swain had based the painting on the records, photographs and descriptions

of Captain Allan Coursins of HMAS Katoomba. He also sourced photographs and

records from the US Navy vessel, USS Peary. The Memorial agreed to commission

Swain to complete the painting. To assist him, the Memorial provided

photographs to Swain, including images of Australian vessels and aerial shots

of Darwin Harbour, as well as topographical maps of the area.

After the fall of Singapore on 15 February, the now

invincible Japanese forces moved quickly south and east through the islands of

the East Indies. Bali fell on the 18th, and Timor was awaiting invasion at any

time. Japanese troops were rapidly drawing close to the Australian mainland,

while the same fast carrier group that had launched the attack on Pearl Harbor

cruised menacingly in the Timor Sea.

Belatedly, it now came home to the Australians that their

homeland was under serious threat of attack, if not invasion, with their

northern port of Darwin first in the line of fire. Yet the Australian

authorities still took no steps to improve the defences of the port, which had

become an important base for the supply of troops and war materials to Java and

Sumatra, both now awaiting a Japanese attack.

The full strength of the Royal Australian Air Force in the

Darwin area consisted of seventeen Hudson light bombers and fourteen Wirraway

fighter patrol planes. Both types were antiques in terms of modern air warfare,

and certainly no match for Japanese fighters and bombers of the day, especially

the Mitsubishi A6M Zero, which had a top speed of 332mph, and was armed with

two 20mm cannon. Visiting the RAAF Base, having arrived on 15 February, were

ten P40 Kittyhawks, one B17 and one B24 bomber of the US Army Air Force, all in

transit to Java. Three PBY Catalinas flying boats of the US Navy were in the

harbour.

Faced with the threat to Timor, the Allied Command took

steps to strengthen the Australian garrison on the island. A convoy consisting

of the Burns Philp ship Tulagi, and the US transports Mauna Loa, Meigs and

Portmar, between them carrying nearly 1,700 Australian and American troops,

left Darwin on the 15th bound for Koepang, on the south-west coast of Timor.

The convoy was well defended, being escorted by the US light cruiser Houston,

the old four-funnelled destroyer USS Peary, and the Australian sloops Swan and

Warrego. However, the transports had no air cover, and when, on the morning of

the 16th, two four-engined Japanese seaplanes appeared, the escorting ships

kept them at a distance with anti-aircraft fire, but could do nothing to stop

them reporting the position and strength of the convoy.

The dive bombers, four squadrons flying in tight formation,

arrived some five hours later. Houston ordered the convoy to scatter, and all

ships began zig-zagging and opened fire on the bombers with every gun that

could be brought to bear. But seemingly oblivious to the curtain of fire put

up, the Japanese came relentlessly on, splitting up into formations of nine

planes each as they singled out the troop transports for their attack.

The Mauna Loa, the largest ship in the convoy at 11,358 tons

displacement, and carrying 500 troops, was the first to come under attack. She

was making violent alterations of course to throw the bombers off their aim,

but at her maximum speed of 10 knots she could not escape. A near miss close to

her No. 2 hold caused her to take on water and killed one crew member and one

soldier. The other transports all had some damage, but thanks largely to the

fierce barrage put up by the escorts, none received a direct hit.

However, once having been detected by the Japanese, the

convoy was ordered to return to Darwin, where it arrived on the 18th. Houston

sailed immediately for Java, but the other ships remained in port, the Tulagi

still having 560 men of the US Army 148 Field Artillery Regiment on board.

On 19 February 1942, Darwin awoke to another busy day.

Including those from the returned invasion convoy, there were now forty-six

ships in the port, berthed alongside, or anchored in the harbour, loading or

discharging supplies, under repair, refuelling, or in the case of the

Australian hospital ship Manunda on standby to receive casualties from the

fighting further north. With so much shipping concentrated in the harbour,

there were many in Darwin who feared they would soon become a target for

Japanese bombers. They were not to be kept in suspense for long.

At 0815 one of the US Navy’s Catalinas, PBY VP22, took off

from the harbour, the roar of its powerful Wasp engines drowning the clatter of

cargo winches coming from the wharves. Piloted by Lieutenant Tom Moorer, the

‘Cat’ was on a routine patrol keeping watch for any threatening Japanese

activity. At 0920 the flying boat was 140 miles north of Darwin, when Moorer

sighted an un-identified merchant ship below. He descended to 600 feet to

investigate, and was immediately pounced upon by eight Japanese Zeros. Moorer

took violent avoiding action, but his plane was raked by cannon fire. The port

engine caught fire, and one of the fuel tanks exploded. With his plane now well

on fire, Moorer quickly lost height, and made an emergency landing on the sea.

He and all his crew were able to evacuate the plane before it blew up.

Fortunately for them, the merchant ship they had been about to investigate was

the Florence D., a supply ship on charter to the US Navy, which was then bound

south for Darwin with a cargo of ammunition. By this time the Zeros had gone

away, leaving the ship free to pick up Lieutenant Moorer and his crew of seven.

The Catalina’s attackers were from a Japanese force consisting

of the aircraft carriers Akagi, Kaga, Hiryu and Soryu which, accompanied by

cruisers and destroyers, had sailed from Palau on 15 February and, quite

unknown to Darwin, were then 250 miles to the north-west of the port. At 0845

these carriers had launched an attack force of eighty-one ‘Kate’ high level

bombers, seventy-one ‘Val’ dive-bombers and thirty-six Zeros. Led by Commander

Mitsuo Fuchida, who had commanded the raid on Pearl Harbor, their target was

the port of Darwin.

Having downed Lieutenant Moorer’s Catalina, the eight Zeros

continued south towards the land, passing over Bathurst Island, 50 miles north

of Darwin, at about 0930. Father John McGraph, who ran the Catholic mission

station on Bathurst, saw the planes passing overhead, correctly identified them

as Japanese, and radioed a warning to the RAAF base at Darwin. It must then

have been obvious to those on the base that an attack on the port was under

way, but for some reason they failed to notify either the town or the ships in

the harbour. The Florence D., meanwhile, had been attacked near Bathurst Island

by Japanese bombers, which sank her. Fortunately, her cargo did not explode,

and only three of her crew of thirty-seven lost their lives. With them died one

of PBY VP22’s crew, who had been plucked from the water only a few hours

before. The survivors were picked up by the Australian minesweeper Warrnambool

and the Bathurst Island Mission boat St. Francis. The Warrnambool was bombed by

a Japanese seaplane while she was involved in the rescue, but suffered no

damage.

The Florence D.’s attackers also came across the 3261 ton

Philippine-flag Don Isidro, also carrying supplies for the US Army, and bound

for Darwin. She received a direct hit and was run ashore on the north coast of

Bathurst. Eleven of her sixty-seven crew died on the beach while awaiting

rescue, which did not come until the 22nd, when the Warrnambool came in to pick

them up. Two others died after the minesweeper returned to Darwin on the 23rd.

Earlier that morning, the USAAF Kittyhawks had taken off

from Darwin on the final leg of their flight to Java, where they were to help

strengthen the defences of the island. Led by Major Floyd Pell, and accompanied

by the B17 bomber, which was acting as navigator, at 0930 the Kittyhawks were

only a few miles on their way when bad weather over Java forced them to return

to Darwin. They were back over the town at 0938, by which time Major Pell had

been notified of a possible Japanese air attack. He allowed five of his flight

to land, keeping the other five in the air to provide cover. His caution

achieved nothing, for at that moment the same Zeros that had shot down Moorer’s

Catalina appeared overhead. The five Kittyhawks still in the air met the Zeros

head-on but they were outgunned, and four out of the five were shot down. The

other Kittyhawks tried to take off again, but, caught at a disadvantage, were

shot down before they could gain height.

There were now no Australian fighters in the air, and if

there had been, the antiquated Wirraways must have suffered the same fate as

Pell’s Kittyhawks. When Mitsuo Fuchida led his bombers in, the skies over

Darwin were clear. Flying in tight formation at between 8–10,000ft, and

ignoring the anti-aircraft fire, the ‘Kates’ attacked first, their target the

closely packed ships in the harbour below. Commander Fuchida reported: ‘The

airfield on the outskirts of the town, although fairly large, had no more than

two or three small hangars, and in all there were only twenty-odd planes of various

types scattered about the field. No planes were in the air. A few attempted to

take off as we came over but were quickly shot down, and the rest were

destroyed where they stood. Anti-aircraft fire was intense but largely

ineffectual, and we quickly accomplished our objectives.’

Stoker 2nd Class Charlie Unmack, serving in the 480 ton

minesweeper HMAS Gunbar, was an early eye-witness:

On the morning of Thursday, 19 February 1942, my ship was

heading out of port and those of us who were not on duty were sitting on deck.

We had not cleared the harbour when we noticed a formation of planes

approaching over East Head. It would have been close to 10.00 am when we first

saw them. The planes were glinting in the morning sun, and we remarked on the

good formation they were keeping.

At first we thought these planes were ours, and then we

noticed some silver-looking objects dropping from them. It was not long before

we knew what they were as they exploded in smoke and dust on the town and

waterfront. More Japanese planes came in from another direction. These were

dive bombers, and they attacked the ships in the harbour. We saw a couple of

planes crash into the sea. I thought they were ours.

Then it was our turn for some attention. They began strafing

us from almost mast height. As the only armament we had against aircraft was a

Lewis machine-gun, and this had been disabled by a Japanese bullet hitting the

magazine pan, the skipper was firing at them with his .45 revolver. This

strafing went on for approximately half an hour before my first taste of action

ended. Our casualties were nine wounded out of a crew of thirty-six, and one of

these died on the hospital ship Manunda on the following day. The skipper had

both knees shattered by Japanese bullets.

We transferred our wounded to the Manunda, and then our

motor boat began rescuing survivors in the water.

The scenes in the harbour during the raid were horrific,

with ships on fire, oil and debris everywhere, ships sinking and ships run

aground …

It was unfortunate that the first ship to be hit was the

5952-ton Burns Philp motor ship Neptuna, which had been requisitioned by the

Admiralty to carry military stores. Under the command of Captain W. Michie, she

had arrived in Darwin on 12 February after loading a cargo at Sydney and

Brisbane, which included 200 depth charges and a very large quantity of

anti-aircraft shells. She was a very vulnerable target.

When the Japanese bombers arrived over Darwin, HMAS Swan was

berthed alongside the Neptuna replenishing her magazines with anti-aircraft

shells from the merchant ship’s hold, having exhausted her supply in defending

the Timor-bound convoy. The transfer of this ammunition was being carried out

by sailors from the sloop. On the shore side of the Neptuna, dockers were discharging

general cargo from the ship onto the wharf. This seemed like a perfectly

sensible arrangement, the Swan being short of shells, but Australian dockers

are sticklers for ‘union rules’, even in wartime. When they realized that

someone else was doing what they rightfully regarded as their work, they

threatened to walk off the ship, so bringing the whole cargo operation to a

standstill. The dispute had become very heated, with the Petty Officer in

charge of the naval party threatening to throw the union delegate into the

dock, when someone noticed the aircraft overhead. Seconds later the bombs began

to fall, and the argument was settled decisively and finally. The Swan cast off

and backed away to give herself room to fire her guns, the ‘wharfies’ ran for the

hills, and the Neptuna’s crew went to their emergency stations. They were not a

moment too soon. A bomb landed on the wharf close to the Neptuna’s bow, the

blast from which damaged her hull, and she began to take on water.

Other bombs followed the first, causing devastation to

nearby installations, including an oil storage tank, from which oil gushed into

the dock, turning the water around the Neptuna black. Then the ship received

two directs hits one after the other, which wrecked much of her superstructure

and started a number of fires. Captain Michie, his chief and second officers

were killed, leaving Third Officer Brendan Deburca to take command. The ship,

which was now listing heavily, was obviously finished, so Deburca wasted no

time in organizing the rigging of a temporary gangway to the shore – the

original gangway had been destroyed by the first bomb – and evacuated all

surviving crew to the wharf.

Once ashore, Deburca called the roll, and established that

in addition to Captain Michie and the deck officers, fifty-two men were

missing: three engineers, a cadet, the three radio officers, and forty-five

Chinese ratings. There was no going back to look for them, for the Neptuna was

now blazing furiously, and with hundreds of tons of ammunition still on board,

she was liable to blow up at any minute. She did in fact explode in a sheet of

flame soon after the survivors were taken off the wrecked wharf by small boats,

and put on board the depot ship HMAS Platypus. One of the survivors died on

board the Platypus, bringing the number lost with the Neptuna to fifty-six.

Another target singled out by the Japanese bombers was the

British Motorist, a 6891-ton motor tanker owned by the British Tanker Company

and commanded by Captain Bates. She carried a crew of sixty-five, and was armed

with a 4.7-inch and a 12-pounder, both mounted aft, and four .303 Lewis

machine-guns. The British Motorist had arrived in Darwin on 11 February

carrying 9,500 tons of diesel oil from Colombo for the Admiralty. She completed

discharging on the 17th and then moved out to an anchorage in the bay, where

she was to carry out engine repairs. Her log book reports that on the morning

of the 19th the weather was extremely good, with light variable airs, a calm

sea, and very good visibility. At about 0930, the Third Officer, who was on

anchor watch on the bridge, saw a V formation of nine aircraft approaching,

which he recognized as being Japanese. He immediately sounded the alarm, and

the tanker’s crew went to their action stations. Second Officer Pierre Payne

wrote a detailed report of what happened next:

On my way to the after gun station I saw a salvo of bombs

explode on the jetty. About 5 minutes later, when standing by the 12 pdr., I

sighted a second wave of nine planes coming in from a south-easterly direction

also in V formation. I saw nine bombs, which were released from a height of

about 10,000 feet, fall about 15 feet from the starboard side of the vessel.

The explosions were terrific and caused the vessel to roll and pitch violently and

it was found that the starboard side and bottom had been blown in and the deck

buckled up in an arch amidships, and, on looking over the side the water could

be seen pouring out of the ballast tanks as she listed … Owing to the height of

the planes, we did not open fire during the attack, as they were out of range

of our guns.

Some Japanese planes then carried out dive bombing attacks,

the planes coming in from a general south-westerly direction, and we were

attacked once or twice but were not hit, the nearest bombs falling about 50

yards away. Meanwhile the other ships in the harbour, the jetty and the town

were attacked, resulting in a great deal of damage being done.

Our 12 pdr. H.A. gun was in action throughout the attack,

and we concentrated our fire on the planes attacking us. Our firing was

effective, definitely disturbing the aim of the attacking planes, which gave us

a lull of about 15 minutes.

I told the gun’s crew to stand by for further developments,

meanwhile the ship was gradually sinking. After a quarter of an hour, at about

1030, we sighted another wave of planes coming in from the south-east. These

planes dropped a salvo of bombs, one of which hit the fore deck, the other

eight being dropped into the sea near the starboard bow. These near misses

caused the ship to pitch and roll; the direct hit made a terrific explosion,

the bridge ladders being blown away and the fore side of the saloon

accommodation and bridge being severely damaged. A great deal of debris was

thrown up into the air, and I could see fire had broken out amidships.

At about 1045 dive bombing was resumed, during which a

direct hit was scored on the port wing of the bridge, destroying all the

midship accommodation, and completely destroying the port lifeboat. I was still

in the main gun pit aft, firing my gun. The Chief Officer was attempting to put

out the fire with the help of other members of the crew, using pyrene fire

extinguishers and a small hand pump. The water service lines were completely

destroyed, and the ship was increasing her list to port.

The Captain had visited the gun position previous to this

latest bombing but had decided to go amidships to direct the machine-gun fire

from the bridge guns and when the bomb exploded both he and the Second Wireless

Operator were very severely injured.

There was one more bombing attack at about 1100 which was

ineffective owing to the accurate fire from our gun which prevented the planes

from taking up a good position …

When the Japanese bombers had gone away, and there was no

sign of any more coming in, Second Officer Payne left his gun and went forward

to ascertain the state of the ship. This was not good. Much of her

superstructure had been destroyed, she was on fire in several places, listing

heavily to port, and seemed to be on the point of capsizing. There was

obviously not much more to be done for her. Captain Bates was lying severely

injured, and the Chief Officer could not be found, so Payne took command and

ordered the ship to be abandoned.

Payne supervised the launching of three lifeboats, and while

this was being done, a number of small naval craft came alongside the tanker,

taking off the injured men and transferring them to the hospital ship Manunda.

The nearest landing point for the lifeboats was the jetty which juts out into

the harbour, but the two ships on each side of the jetty, had been hit and were

burning. Oil had spilled from their ruptured tanks into the water, and this too

was on fire. Payne decided to take his lifeboats to the nearest beach, which

proved to be a wise precaution. As they were passing within 100 yards of the

jetty, one of the ships, the Zealandia, blew up, throwing burning debris in all

directions.

When the British Motorist’s boats reached the shore, the

survivors reported to the company’s agent in the town, but such was the state

of confusion reigning in Darwin that he could do nothing for them, except to

take a list of their names. No food or shelter was available, so Payne led his

men back to the beach, where for the next two days they camped out alongside

their boats, living off the emergency provisions they carried. At last, on the

22nd, they were accommodated at an old hospital building near the beach, and

were fed by the Army. The last they saw of their ship was her lying capsized,

with her port side, most of which had been ripped open by the bomb blasts,

about 3 feet above the water. The British Motorist would never sail again.

The Burns Philp ship Tulagi, participant in the ill-fated

Timor convoy, was also anchored in the harbour, and still had 560 US Army men

on board. When she came under attack from the air, her master, Captain

Thompson, slipped his anchor and ran the ship aground in a muddy creek with the

object of landing his troops before the Japanese planes came in again. Using

lifeboats and rafts, all troops and crew were put ashore, and the ship

temporarily abandoned.

Next afternoon, Captain Thompson reboarded the Tulagi, but

only five members of his crew, one engineer, three wireless operators and the

Purser, volunteered to come with him. With the assistance of a naval working

party and some of the Neptuna’s officers, the Tulagi was floated off the mud

and re-anchored in the harbour. Nine days later, after repairs had been carried

out, she left Darwin for Sydney, crewed by volunteers from the Neptuna, the

British Motorist, and a naval party consisting of a Chief Petty Officer and six

ratings.

HMAS Swan, having pulled clear from the Neptuna before she

blew up, did not escape the attentions of the enemy planes. Despite the

extremely accurate anti-aircraft fire she put up, she was attacked on seven

separate occasions. Several near misses caused considerable damage to the

sloop, three of her crew were killed and nineteen injured.

USS Peary, the largest naval ship berthed in Darwin at the

time of the raid, for all her great age, carried a formidable anti-aircraft

armament of six 3-inch dual-purpose guns, and these she put to good use when

the Japanese planes came over. But at 1045 she became the main target of the

‘Kate’ dive-bombers, and was hit by five bombs in quick succession. The first

bomb exploded right aft, over her steering gear, the second, an incendiary, hit

the galley deckhouse, the third failed to explode, the fourth dropped on the

fore deck, causing her forward magazine to blow up, and the fifth, also an

incendiary, landed in the after engine-room, completely wrecking it.

The American destroyer was hard hit, on fire, and sinking,

but she was not about to give up without a fight. Her six 3-inch guns hurled

their shells skywards as fast as their crews could load and fire, while the two

machine-guns mounted aft raked any of her attackers that dared to come within

their range. All guns continued to fire until the Japanese planes had gone

away, by which time the Peary’s after deck was under water. She finally sank

stern first at 1300. Eighty-one of her total complement of 136 died, and

thirteen were injured.

Darwin’s first air raid was over by 1040, when the Japanese

planes, their mission accomplished, returned to their carriers. In a momentous

forty minutes, they had sunk ten Allied ships, including the Florence D. and

the Don Isidro, and damaged many others. A total of 187 people were killed in

those ships, while another 107 were left injured, some seriously. In addition,

twenty-two of the dock workers engaged in discharging the Neptuna lost their

lives when they were trapped on the jetty by burning oil.

While the bombs were falling on Darwin’s harbour, the

hospital ship HMAHS Manunda found her services to be very much in demand. The

8853-ton ex-Adelaide Steamship Company’s passenger liner, under the command of

Captain James Garden, had arrived in Darwin on 14 January, and over the

intervening weeks her medical staff, led by Lieutenant-Colonel John Beith, had

been in constant training to cope with the casualties that the war, which was

moving ever nearer, might bring.

When the Japanese bombers arrived over Darwin on the morning

of 19 February, the Manunda, although she must have been easily recognized as a

hospital ship by her white painted hull and prominent red crosses, soon became

a prime target. A near miss sprayed her decks with lethal fragments of

shrapnel, causing widespread damage and a number of casualties. A second bomb

narrowly missed her bridge and exploded on B and C decks, totally destroying

the medical and nursing quarters and starting a number of fires, which could not

be controlled as the fire mains were cut.

Eleven members of the Manunda’s crew were killed, including

Third Officer Alan Scott Smith, eighteen were seriously wounded, and forty

others slightly wounded. Three of her medical staff, including Nursing Sister

Margaret De Mestre and Captain B.H. Hocking, a dentist, lost their lives. In

spite of the terrible carnage wrought by the Japanese bombs, the Manunda

continued to function as a hospital ship, using her boats to pick up hundreds

of casualties from the wrecked ships in the harbour and from the water. When

she sailed for Fremantle in the early hours of the 20th, she had on board 266

wounded, many of whom were stretcher cases.

While the Japanese dive bombers concentrated on the ships in

the harbour, the high-level ‘Vals’ had been systematically bombing the town of

Darwin. The devastation they caused was widespread. One of the first buildings

to be hit was the Post Office, where the Postmaster, his family and all the

staff on duty were killed. The Police Barracks, the Police Station, Government

House, the Cable Office, and the local hospital, along with a number of private

houses were all either hit or damaged by blast. And no sooner had the people of

Darwin recovered from the shock of this raid than they found themselves under

attack again. A few minutes before noon, the air was once more filled with the

sound of high-flying aircraft. This second wave of Japanese planes consisted of

fifty-four twin-engined land-based bombers flying from Kendari, in the island of

Sulawasi and from Ambon. They had no fighter escort, not did they need one, for

all Darwin’s air defence force had already been crushed. Ignoring the sporadic

anti-aircraft fire, they proceeded to pattern-bomb the RAAF airfield,

destroying eight aircraft still on the ground and most of the buildings, and

causing serious damage to the hospital.

In the two raids on Darwin that day, a total of 243 Japanese

planes dropped 628 bombs, nearly three times the number dropped on Pearl

Harbor. No exact figure is on record of the number of civilians killed in the

town of Darwin during the raid. Army Intelligence sources at the time put the

figure at 1,100, while the Mayor of Darwin estimated that 900 had been killed.

The Australian Government, on the other hand, anxious to avoid any panic,

claimed that casualties amounted to only seventeen killed and thirty-five

injured. Their reassurances fell on deaf ears. The population of Darwin was

convinced that a Japanese invasion was only hours away and streamed out of the

town, heading south in what became known later as ‘The Adelaide River Stakes’.

At least half of the civilian population left, the panic spreading to the

Australian servicemen based in Darwin, who deserted their posts in great

numbers. Three days after the attack, 278 soldiers and airmen were still

missing.