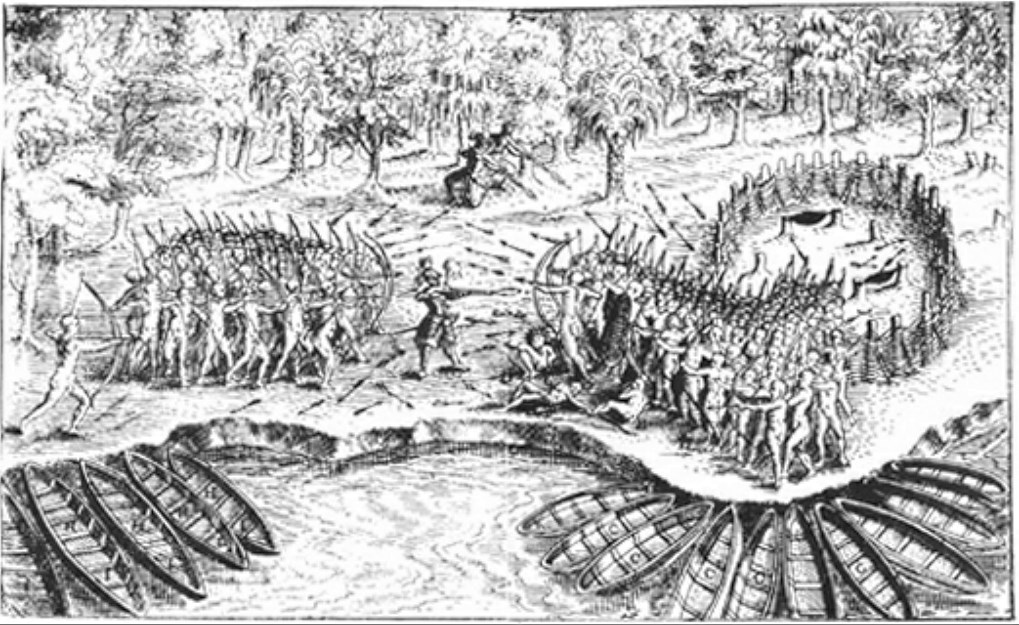

Champlain’s battle against the Iroquois near Ticonderoga in 1609.

Behind the French officer are his Huron and Algonquin allies.

Huron warrior wearing slat armour, from Champlain’s Voyages of 1619.

Ste. Marie Among the Hurons, an overview. This oblique artist’s

representation shows the extent of the Jesuit headquarters in Huronia.

Huronia in the 1600s, showing the relationship of some Huron villages

to modem communities.

The story of the first Europeans in central Canada is the

story of the struggle to control the fur trade. To any European furs were a

great bargain. Although some items exchanged for furs were useful, such as

knives, axes, kettles and cloth, many were cheap trinkets, or liquor, which did

unpardonable harm to native people unaccustomed to it. The European appetite

for furs was insatiable, and the quest to find new areas where animals were

plentiful led to the exploration of more and more of the interior.

In the process the natives developed such an appetite for

trade goods that competing European powers were able to form alliances with

individual nations or tribes to keep the Indians divided. United, they might

have been able to preserve their territories and way of life much longer. The

natives helped the newcomers by showing them how to live as they did; otherwise

the interlopers would not have taken control of the country so easily. European

penetration of the interior was done with native cooperation. The destruction

of Huronia – the land of the Huron Indians – came about as a consequence of

these alliances and rivalries.

New France began in 1608 when Samuel de Champlain founded

his little settlement of traders at Quebec, choosing the site for its defence

possibilities. If the French were to survive they needed allies. Champlain was

quick to perceive the disunity that prevailed among the different nations. By

accompanying some Huron and Algonquin warriors to attack the Iroquois in the

vicinity of Lake Champlain in 1609, Champlain committed France to an alliance

with these nations. Henceforth the warriors of the five Iroquois nations –

Mohawks, Oneidas, Onondagas, Cayugas and Senecas – were France’s enemies

despite certain successes when the French lured some Iroquois close to Montreal

to live. The real losers in the struggle between France and the Iroquois were

the Hurons.

The Hurons and the Iroquois shared an Iroquoian language,

and their longhouses in stockaded villages, and the fields where corn, beans

and squash were grown on mounds were similar. Otherwise they were rivals who

had fought each other long before the arrival of Europeans – a rivalry that the

Dutch and French, and later the English, could exploit.

Huronia, the country of the four nations that made up the

Huron, or Wendat, Confederacy, lay between Lake Simcoe and the shores of

Georgian Bay. The Hurons, whose numbers have been estimated as 16,000 at the

time of their first contact with Europeans, were a trading people. Their own

country, where they practiced their shifting agriculture and lived in some

eighteen villages, was not rich in beaver. They traded with tribes farther

afield and sold pelts to French traders. The members of the Iroquois

Confederacy, whose tribal lands lay south of the Great Lakes, had a similar

trading relationship with the Dutch in the 1600s, when they had a fur fort at

Albany.

No one specific site can be called a battlefield, but a

number of archaeological sites have been identified. The most important is

Sainte Marie among the Hurons, near Midland, which has been restored, even to

locks on the Wye River that runs through this Jesuit mission to the Huron

people. At a visitors’ centre a film recreates life in the mission. Above

Sainte Marie on the hill stands the Shrine, built to commemorate the six

priests and two lay brothers who were killed by the Iroqouois. More of the

Huron way of life is shown at the Huronia Museum and a reconstructed Huron

village in Little Lake Park, Midland.

Four other sites have been identified and marked. One is St.

Ignace II. A plaque marking the site is on the south side of Highway 12 between

Coldwater and Victoria Harbour in Tay Township. Cahiagué, an important Huron

village, has been partly excavated, near Warminster, fifteen kilometres west of

Orillia off Highway 12. A marker in Victoria Harbour commemrates the St. Louis

mission; the site is about three kilometres up the Hogg River. Sainte Marie II

is on Christian Island, the marker on the east side of the island above the bay

and close to the shore.

The first Frenchman to live in what is now Ontario was

Etienne Brulé, a teen-aged servant of Samuel de Champlain. At Tadoussac in

1609, New France’s first governor met some Hurons who had come to trade their

furs. Champlain decided to send young men to live among these natives to learn

their language and customs. When more Hurons came with furs the following year,

Champlain sent Brulé home with them. He spent the winter of 1610-1611 in

Huronia, but the exact location is uncertain. (The first Englishman to visit

Ontario was spending the same winter in James Bay. He was Henry Hudson, and his

ship Discovery was frozen in for the season.)

Trade was a powerful motive for having contact with the

Indians. The propagation of the gospel of Christianity was another, especially

for the French. Almost from their first contacts with the natives, the French

sent Roman Catholic missionaries among them. The first missionary to the Hurons

was Father Joseph Le Caron, in the grey robes of the Récollet order, who, in

1615, travelled with some guides up the Ottawa River, along Lake Nipissing and

the French River to Lake Huron, thence to Huronia. Not many days later Champlain

followed the same route, accompanied by some Frenchmen and native guides. In

Huronia he found that a large war party was forming at Cahiagué to go to attack

the Iroquois in their own country. Impressed by the Frenchmen’s ‘fire sticks’

the warriors asked Champlain and his men to accompany them, and the governor

agreed.

South of Huronia was the country of the Petuns, and along

Lake Erie that of the Neutrals. Like the Hurons and Iroquois, the Petuns and

the Neutrals spoke an Iroquoian language. The latter two tried to avoid the

rivalry that existed between the Wendat and Iroquois Confederacies. The war

party Champlain and his men accompanied travelled by canoe through the Kawartha

Lakes and the Trent River to Lake Ontario, and from there they ascended the Oswego

River into the country of the Oneidas. The Hurons were defeated and forced to

withdraw. Champlain received an arrow in the leg and was taken back to the

Huron country to recuperate. When he returned to Quebec the following year,

Father Le Caron went with him.

For a time the French missionaries concentrated their

efforts at conversion among the tribes of the eastern woodlands — nomadic

hunters who were not easy to find. Hoping for better luck with natives who

lived in more permanent agricultural villages, the Missionaries turned their

attention to Huronia. Several Récollets went there, and more of Champlain’s

young men joined Etienne Brulé.

The Récollets were a very poor order, lacking the money for

an effective mission, and consequently, they invited the wealthy Jesuit order

to join them. The first black-robed Jesuits arrived in Quebec in 1625. At that

time the Récollet, Nicolas Viel, living in a cabin at the Huron village of

Toanaché, on the west shore of Penetanguishene Bay, was exhausted. He set out

for Quebec to have a rest, but his canoe was swamped in the rapids near the

Island of Montreal and he drowned.

In 1626 three priests went westwards – the Récollet La Roche

de Daillon, and Jesuits Jean de Brébeuf and Anne de Nouë. They occupied Father

Viel’s cabin at Toanché, where Brébeuf remained for three years. The other two

left in 1628.

In 1629, Captain David Kirke was sent with three ships to

Quebec to capture the stronghold for England. Etienne Brulé and Nicolas

Marsolet went to pilot in a French fleet Champlain was expecting. Instead,

Brulé and Marsolet met Kirke’s ships at Tadoussac and agreed to guide them into

Quebec’s harbour. Champlain surrendered, and Kirke sent the governor and all

the missionaries back to France. Three years later, in 1632, by the Treaty of

St. Germain-en-Laye, Canada was returned to France. Etienne Brulé, living at

Toanché, was murdered by the Hurons, who feared Champlain’s wrath if he caught

them sheltering the turncoat. Thus ended the life of the first Frenchman to

explore Ontario.

Champlain returned from France, accompanied by black-robed

Jesuits but no Récollets, for economy reasons. The Jesuits could pay their own

way. In 1634 the Jesuit Fathers, Jean de Brébeuf, Antoine Daniel and Ambroise

Davost, with some hired men, went to Huronia. At Ihonatiria, near the northern

tip of the Penetanguishene peninsula, they started a mission named St. Joseph.

During the 1635 growing season, both drought and disease

struck Ihonatiria, and the survivors left the village. When new Jesuits arrived,

Brébeuf moved to the village of Ossossané on Nottawasaga Bay, and opened a new

mission, La Conception de Notre Dame. In 1637, Father Jérôme Lalemant opened

another mission, St. Joseph II, at Teanaustayé on the upper reaches of the

Sturgeon River.

Seeing the need for a well-fortified, centrally-located

mission, Lalemant built Sainte Marie (now restored) on the shore of wye River.

His workmen opened the first canal in central Canada, with three small locks to

divert water within the stockade of Sainte Marie. The Hurons began to trust the

missionaries but these were also years when new diseases swept the country. The

well-meaning priests and their helpers, all unaware, were the cause of these

misfortunes. Measles and smallpox, introduced by Europeans, took a fearful toll

despite the efforts of the missionaries to care for the sick.

In the 1640s, when the Hurons had been weakened by disease,

the Iroquois saw their opportunity to end the threat posed by the Wendat-French

alliance, and to gain control of the fur trade for themselves. Both native

confederacies wanted the fire sticks but the French were reluctant to trade

such weapons. The Dutch had no such scruples, and they supplied their Iroquois

allies with muskets and ammunition. In 1642 the Iroquois attacked the Huron

village of Contarea, near the shore of Lake Simcoe (south of Orillia), killed

everyone they found, and put the settlement to the torch. Next, they isolated

the Hurons by occupying lands along the Ottawa River that belonged to the

Algonquin tribe, cutting off communication with Quebec for months, since they

also had villages close to the St. Lawrence.

In 1645, Father Jérôme Lalemant left Huronia and the new

Superior was Father Paul Ragueneau, who was based at Sainte Marie. By that time

the Jesuits had fifty-eight men in Huronia — twenty-two soldiers, eighteen

priests, the rest engagés who were allowed to earn money trading, or donnés who

were unpaid volunteers. The Jesuits had opened a dozen missions, nine to the

Hurons, and three among the Petuns and Algonquins. Land around Sainte Marie had

been planted with crops so that the Black Robes, as the Hurons called them,

could feed the hundreds who visited them.

The first of the Jesuit martyrs met their fate in 1646.

Emboldened by their success in Huronia, the Jesuits attempted to found a

mission to the Iroquois. They chose Father Isaac Joques, who had been in

Huronia but was then on the Island of Montreal, to go into the Mohawk Valley.

In late August, Father Joques set out, accompanied by a lay brother, Jean de

Lalande. The Mohawks killed them, placed their heads on a palisade, and threw

their bodies into the Mohawk River.

At Teanaustayé, Father Antoine Daniel was in charge of St.

Joseph II mission. On 4 July 1648, the Iroquois attacked, and Father Daniel was

among those killed. On 14 March 1649, they struck the mission of St. Ignace, on

a tributary of the Coldwater River. Hurons fleeing from St. Ignace stopped at

St. Louis mission, to the west, to warn the two missionaries then living there,

Fathers Jean de Brébeuf and Gabriel Lalement (a nephew of Father Jérôme

Lalement). The two priests refused to desert their flock at St. Louis and both

were subsequently tortured to death. Word reached Sainte Marie, where Father

Ragueneau decided to evacuate the mission. A war party of Hurons headed for St.

Louis mission (on the Hogg River south of Victoria Harbour) to try and turn

back the Iroquois. They fought furiously while Father Ragueneau and his

followers burned Sainte Marie. The black robes and some Hurons headed for

Christian Island for safety, and there they started a second Sainte Marie.

While the destitute Hurons fled to the new Sainte Marie for

succour, the Iroquois attacked the three missions to the Petun and Algonquin

Indians, and they killed Fathers Charles Garnier and Nöel Chabanel. At Sainte

Marie II, the winter was exceedingly severe, for there was not enough food on

the island for all the refugee Hurons. In the spring Father Ragueneau evacuated

the mission, and with about sixty Frenchmen and 300 Hurons, he set off in

canoes for Quebec. The Jesuits’ plan for Huronia had ended in flames at the

hands of the Iroquois.

Now the Iroquois turned on the rest of the Petuns, and on

the Neutrals, killing them and driving the survivors west and south; later they

regrouped and called themselves Wyandots. When the warriors of the Iroquois

Confederacy returned to their own country deep inside New York State, the lands

of their fellow-Iroquoians lay desolate and deserted. Gradually the

Mississaugas, who spoke an Algonkian language, drifted southwards and hunted

through the once fertile fields.

In 1664, England wrested the colony of New Netherlands from the Dutch and renamed it New York. The change only intensified the rivalry over the fur trade, and convinced the French to move farther inland. As beaver disappeared from one area through over-trapping, explorers moved on in search of new territory where the animal was still plentiful. As the fur traders moved on towards the west, so did the missionaries, until Britain finally succeeded in acquiring New France slightly more than a century after the demise of the Jesuit missions to Huronia.