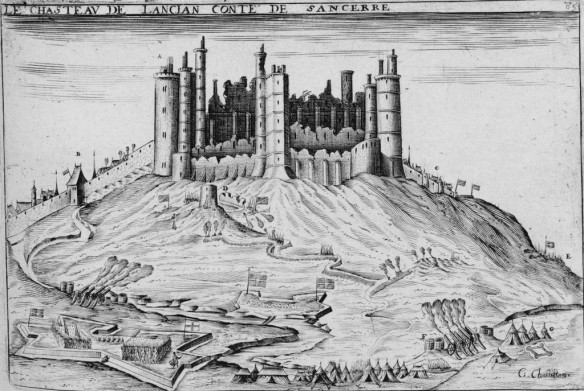

Siege de Sancerre, early 17th century print by Claude Chastillon.

Portrait du maréchal de La Châtre

Huguenot Gendarmes 1567.

In a blistering moment of France’s Wars of Religion, the hilltop town of Sancerre would suffer an agonizing siege. It was a Huguenot stronghold, walled in and built around a fortress. Overlooking the Loire, the town was located about a hundred miles west of Dijon. The siege came at the end of a chain of murders involving the slaughter of more than three thousand Huguenots in different parts of France. But the killing orgy had started in Paris on August 23–24, 1572, the Eve of St. Bartholomew’s Day, with the massacre of about two thousand people.

That autumn Sancerre took in five hundred Huguenot refugees—men, women, and children. The town’s remaining Catholics fell to a small minority. In late October, a prominent nobleman from the region, Monsieur de Fontaines, turned up suddenly, hoping to enter and seize control. Refusing to promise the Huguenots the right of worship, with the claim that he had no such charge from the king, he was refused entry to the town, whereupon he replied that he knew what he would have to do. It was war. Less than two weeks later, a tempestuous attack on the citadel was repelled.

Now, fearing a siege, the Sancerrois began to examine their stocks of food and other resources. I draw the following narrative from one of the most remarkable eyewitness chronicles in the history of Europe: Jean de Léry’s Histoire memorable de la Ville de Sancerre, published in the Protestant seaport of La Rochelle less than two years after the siege.

Born in Burgundy, at La Margelle, Jean de Léry (1534–1613) became a Protestant at the age of eighteen and spent the better part of two years (1556–1558) as a missionary in Brazil, about which he published a famous account, Histoire d’un voyage fait en la terre du Bresil, autrement dite l’Amerique. Later, after a second stint of study in Geneva, he returned to France to preach the word of God as a Calvinist minister. Fearing for his life in the wake of the August massacres of 1572, he fled to Sancerre in September. And here Léry would become one of the foremost leaders in the Huguenot campaign of resistance.

Since the kings of France were prime movers of the Italian Wars (1494–1559), Italy became a school of warfare for thousands of French noblemen, with the result that France’s religious wars would be captained by seasoned officers on both sides of the confessional divide. Sancerre had more than enough of these in November 1572, in addition to 300 professional soldiers and another 350 men who were being trained in the use of arms. There were also 150 smalltime wine producers who would serve as guardsmen along the town’s defensive walls and gates. At the peak of the fighting, the night watch would even include a number of bold-spirited women armed with halberds, half pikes, and iron bars. They concealed their sex by wearing hats or helmets to hide their long hair.

From November onward, the countryside around Sancerre rang out with frequent and bloody skirmishes, provoked mostly by the Huguenot defenders, who made daring sorties into the surrounding country to fight the enemy, seize supplies, or gather provisions for the coming siege. By December they were stealing grain and livestock in night raids. On the night of January 1–2, for example, they broke into a neighboring village and returned to Sancerre with “the priest of the place as their prisoner and four carts loaded with wheat and wine, plus eight bullocks and cows for feeding the town.” Raids of this sort went on right through the winter, but became bloodier, less frequent, and more dangerous as the gathering royal army swelled and tightened its ring around Sancerre. Meanwhile, the town itself would know internal wrangling as the mass of refugees provoked disagreements, or blaspheming soldiers offended Huguenot ears, and the pride of competing officers clashed.

By the end of January, the enemy forces massed around the base of the Sancerre “mountain” numbered about sixty-five hundred foot soldiers and more than five hundred horsemen, not counting volunteer gentlemen and others from the surrounding area. By January 11, the people of Sancerre had resolved, in a general assembly, “that the poor, a number of women and children, and all those who could not serve, apart from eating, should be put outside the town.” But the men charged with this repugnant task failed to carry it out, “partly because of giving way to the outcry raised. And so they put no one outside the town gates.” This, Léry observes, was a grave error, because at the time the unwanted could easily have departed and gone wherever they chose, “which would have prevented the great famine … and which [later on] caused so much suffering.”

The Sancerrois did not even bother to answer the regional governor’s call to surrender, made on January 13. Claude de La Châtre informed them that his troops were there to subjugate Sancerre, in accord with the king’s orders, so he and his men now began to dig in seriously, both by building a network of trenches and fortifying the houses in the village of Fontenay, at the foot of towering Sancerre. They hauled in artillery early in February and soon began a daily bombing of the Huguenot fortress. In four days, from February 21 to 24, the town took more than thirty-five hundred cannon shots. Léry speaks of “a tempest” of bombs, debris, and house and wall fragments “flying through the air thicker than flies.” Yet very few people were killed—it was God’s doing, he opines—and the attackers were dumbfounded.

That winter, Léry points out, the weather was dreadfully cold, with a great deal of ice and snow, and for this the Huguenots praised God, because it was especially hard on the encamped enemy soldiers. La Châtre, nonetheless, was already having Sancerre undermined, with an eye to planting explosives and blasting breaches in the town walls.

Léry’s comments on the weather were revelatory. In the Europe of that day, there was an all but universal feeling in towns under attack that time destroyed besieging armies by working through hunger, painful discomfort, disease, and desertion. Living in squalid conditions, mercenaries were likely to succumb to malnutrition, wounds, and sickness; and desertion was a tempting solution, particularly when men stole off in pairs or in small groups. One thing was almost certain: Though a besieging army might begin with money in its pockets, as the weeks passed, that money ran out and desertion became more and more enticing. So, when not negotiating an immediate surrender, the best hope for a besieged town was to hold out for as long as possible until, in despair, the ragged remainders of the besieging army pulled away. To hold out, however, the besieged had to have ample stores of food.

Warned by a prisoner, the Sancerrois were ready to receive and repel a major assault on March 19, preceded by mine explosions and a furious bombardment. The assault was repelled, and Léry, in his description, touches fleetingly on a girl who had been working near him, carrying loads of earth for the defenders, when she was hit by a cannon shot and disemboweled before his eyes, “her intestines and liver bursting through her ribs.” Dead on the spot. His own survival, he felt, was God’s work. The defenders lost seventeen soldiers and the girl, but enemy casualties amounted to 260 dead and 200 wounded.

The bombardment of Sancerre continued, but always, Léry observes, with little loss of life in the town. When the royalists erected two towering, wheeled structures near the walls, with arquebusiers on the top, aiming volleys at the defenders on the walls, groups of Huguenot soldiers made stealthy nighttime attacks and set fire to them. Throughout their many armed engagements, seeking to maintain unity and to keep up their spirits, the besieged Huguenots sang hymns, flagging their evangelical bent. Yet all the while a silent enemy was slowly taking shape, and it was to be more fatal than the daily cannonades of the royalists. It was taking form around their dwindling food supplies. There was wine galore, but beef, pork, cheese, and—most important—flour were running out, with the remaining stocks turning, in value, to gold.

The Sancerrois sent messengers to Protestant communities in Languedoc to plead for military help, but there, too, the Huguenots were at war. Step-by-step, in the teeth of shrill complaint, Sancerre’s town council was forced to commandeer all wheat still in private hands and to put it into central storage for communal bread.

In March and April, they slaughtered and cooked their donkeys and mules, used for transport up the town’s steep rise of more than 360 meters, until all had been eaten up by the end of April. Later, as the siege continued, they would regret having consumed their pack animals with such greedy abandon. In May, they began to kill their horses, the council ruling that these had to be slaughtered and sold by butchers. Prices were fixed at sums that were lower than would have been allowed for by the tightening pincers of supply and demand. But in July and August, as Sancerre went to the wall, prices for the remaining horse meat soared, despite strict policing; and every part of the horse was sold, including head and guts. Opinion held, Léry observes, that horse was better than donkey or mule, and better boiled than roasted. He was coldly reporting, but also, possibly, adding a sliver of gallows humor.

Then came the turn of the cats, “and soon all were eaten, the entire lot in fifteen days.” It followed that dogs “were not spared … and were eaten as routinely as sheep in other times.” These too were sold, and Léry lists prices. Cooked with herbs and spices, people ate the entire animal. “The thighs of roasted hunting dogs were found to be especially tender and were eaten like saddle of hare.” Many people “took to hunting rats, moles, and mice,” but poor children in particular favored mice, “which they cooked on coal, mostly without skinning or gutting them, and—more than eating—they wolfed them down with immense greed. Every tail, foot, or skin of a rat was nourishment for a multitude of suffering poor people.”

June 2 brought a decision to expel some of the poor from the town, although their numbers had already been reduced by starvation and disease. That very evening “about seventy of them departed of their own accord.” And the essential ration was now lowered to one half pound of daily bread per person, irrespective of rank or social condition, soldiers included. Eight days later this ration was reduced to a quarter pound, then to one pound per week, until flour supplies ran out at the end of June.

But the imagination of the starving Sancerrois found more to eat than any of them could ever have dreamed of, and it was in the leather and hides that came from “bullocks, cows, sheep, and other animals.” Once these were washed, scoured, and scraped, they could be gently boiled or even “roasted on a grill like tripe.” By adding a bit of fat to the skins, some people made “a fricassee and potted pâté, while others put them into vinaigrette.” Léry goes into the fine details of how to prepare skins before cooking them, noting, for example, that calfskin is unusually “tender and delicate.” All the obvious kinds “went up for sale like tripe in the market stalls,” and they were very expensive.

In due course, the besieged were eating “not only white parchment, but also letters, title deeds, printed books, and manuscripts.” They would boil these until they were glutinous and ready to be “fricasseed like tripe.” Yet the search for foods did not terminate here. In addition to removing and eating the skins of drums, the starving also ate the horny part of the hooves of horses and other animals, such as oxen. Harnesses and all other leather objects were consumed, as well as old bones picked up in the streets and anything “having some humidity or taste,” such as weeds and shrubbery. People mounted guard in their gardens at night.

And still the raging hunger went on, pushing frontiers. The besieged ate straw and candle fat; and they ground nutshells into powder to make a kind of bread with it. They even crushed and powdered slate, making it into a paste by mixing in water, salt, and vinegar. The excrement of the eaters of grass and weeds was like horse dung. And “I can affirm,” Léry asserts, all but beggaring belief and alluding to Jeremiah’s lamentations, “that human excrement was collected to be eaten” by those who once ate delicate meats. Some ate horse dung “with great avidity,” and others went through the streets, looking for “every kind of ordure,” whose “stink alone was enough to poison those who handled it, let alone the ones who ate it.”

The final step was cannibalism, which must already have been taken, sooner than Léry himself could know. He turns to the subject by first citing Leviticus 26 and Deuteronomy 28, with their references to the starving who ate their children in sieges, and then says that the people of Sancerre “saw this prodigious … crime committed within their walls. For on July 21st, it was discovered and confirmed that a grape-grower named Simon Potard, Eugene his wife, and an old woman who lived with them, named Philippes de la Feuille, otherwise known as l’Emerie, had eaten the head, brains, liver, and innards of their daughter aged about three, who had died of hunger.” Léry saw the remains of the body, including “the cooked tongue, finger” and other parts that they were about to eat, when caught by surprise. And he cannot refrain from identifying all the little body parts that were in a pot, “mixed with vinegar, salt, and spices, and about to be put on the fire and cooked.” Although he had seen “savages” in Brazil “eat their prisoners of war,” this had been not nearly so shocking to him.

Arrested, the couple and the old woman confessed at once, but they swore that they had not killed the child. Potard claimed that l’Emerie had talked him into the deed. He had then opened the linen sack containing the body of the little girl, dismembered the corpse, and put the parts into a cooking pot. His wife insisted that she had come on the two of them as they were doing the cooking. Yet on the very day of their arrest, the three had received a ration of herbal soup and some wine, which the authorities had regarded as enough to get them through the day.

Looking into the life of the Potards, the town council found that they had a reputation for being “drunkards, gluttons, and cruel to their other children,” and that they had lived together before they actually married. It was found, indeed, that they had been expelled from the Reformed Church, and that he, Simon, had killed a man. The council now took swift action. He was condemned to be burned alive, his wife to be strangled, and l’Emerie’s body was dug out of its grave and burned. She had died on the day after their arrest.

Lest any of his readers should think the sentence too harsh, Léry remarks, they “should consider the state to which Sancerre had been reduced, and the consequences of failing to impose a severe penalty on those who had eaten of the flesh of that child,” even if she was already dead. “For it was to be feared—we had already seen the signs—that with the famine getting ever worse, the soldiers and the people would have given themselves not only to eating the bodies of those who had died a natural death, and those who had been killed in war or in other ways, but also to killing one another for food.” People who have not experienced famine, he adds, cannot understand what it can call forth, and he reports a curious exchange. A starving man in Sancerre had recently asked him whether he, the unnamed man, would be doing evil and offending God if he ate the “buttocks” (fesse) of someone who had just been killed, especially as the part seemed to him “so very pleasing” (si belle). The question struck Léry as “odious” and he instantly replied that doing so would make the eater worse than a beast.

In the meantime, there had been another purge of poor folk. Many of them had been ejected from the town in June. As expected, however, the besiegers blocked their passage at the siege trenches, killed some, wounded others, no doubt mutilating the faces of a few, and then, using staves, battered the rest back to the walls. Unable to reenter Sancerre, the outcasts lived for a while by scrounging about for grape buds, weeds, snails, and red slugs. In the end, “most of them perished between the trenches and the moat.” But the inner spaces of the town itself offered no guarantees. There, too, people died at home and in the streets, children more often, and those “under twelve nearly all died,” their bones sometimes “piercing the flesh.”

Murmuring was to be heard by late June. The rabidly hungry, their voices rising, wanted Sancerre to surrender. The town, however, was in the clasp of religious hard-liners, of the better-off, and of soldiers. Hence the complainers were ordered to shut up or get out of town. Otherwise, came the warning, they would be thrown from the town’s soaring walls. Sancerre was an island in a vast countryside of hostile Catholics. Yet the starving kept stealing away, passing over to the enemy even when threatened with death, knowing, in any case, that they faced a sure death in that walled-in fortress. As late as July 30, seventy-five soldiers paraded through the streets in testimony of their will to hold out for “the preservation of the [true] Church.” But they were a minority, for at that point Sancerre still had at least another 325 soldiers. Then, on August 10, affected by rumors about Huguenot losses in other parts of France, the despairing garrison captains announced that the army was ready to surrender, that they preferred to die by the sword rather than hunger. A debate in council ignited passions, differences broke out, tempers flared, and men drew out swords and daggers. But by the next day common sense had prevailed.

Informal negotiations with the enemy, already broached, revealed that the commander of the siege, La Châtre, was ready to spare all their lives. Talks went on for over a week. The countryside was a waste for thirty miles in all directions around Sancerre. Surrender terms were finally fixed and approved on the nineteenth.

In a changed climate and in accord with the king’s new mandate, the Sancerrois could go on worshipping as Huguenots. The honor and chastity of their women would be respected. They retained full rights over all their goods and landed properties. There would be no sequestrations. However, they had to face a fine of 40,000 livres, intended as pay for the besieging army. It was a sum that would undo the well-off families; hence residents were given the bitter right to sell, alienate, or remove any or all of their goods.

On the twentieth of August, bread and meat began to arrive from the outside. And now, in the moving about of people, Léry was the first man to be let out of Sancerre. Although he had negotiated the surrender agreement for the besieged, he was provided with a special pass and accompanied by several soldiers, because La Châtre feared that he might be assaulted, owing to his office as pastor. The enemy also maintained that he was the one who had taught the Sancerrois how to survive on leather and skins. Léry was followed out of Sancerre by the Huguenot soldiers, some of whom were accompanied by wives and children.

La Châtre seems to have offered his surrender terms in good faith. But he was rushing off to a royal assignment in Poland, and in the furies of the time, it was going to be next to impossible for the king’s ministers to guarantee the terms. Hatreds were intense, and Sancerre presented a chance for plunder.

Priests and monks entered the town at the end of August. Catholics began to dismantle walls and defensive points. They removed the town clock, the bells, “and all the other signs” of a busy municipality, in effect reducing Sancerre to the level of a mere village. Many houses, especially the empty ones, were robbed and stripped of their furniture. In due course, residents who sought to leave Sancerre were compelled to pay ransoms. And those who remained, although seeing some of their possessions confiscated, had to pay special taxes, leaving them, in the end, all but destitute. In time their church was suppressed. The destiny of Calvinism in France would be hammered out in Paris, La Rochelle, Rouen, and other cities.

Once it was published, Léry’s memoir transformed the siege of Sancerre into an event of legendary resistance, particularly among Huguenots. But the strange foods of the famine intrigued all who heard about them. Had the eating of “powdered slate” actually taken place? Some of the foods seemed to lie beyond the utmost limits of the imaginary. Paris was to learn a thing or two from Léry’s recipes.

Since the Huguenot pastor soon rushed his memoir into print, it is likely to carry moments of exaggeration and even of fiction, particularly with regard to the scale of the cannonades directed against Sancerre. His general outlines of the siege, however, and of the wild workings of hunger, are perfectly in accord with the consequences of sieges in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.