Theodor Tolsdorff was born in Lehnarten, East Prussia, on November 3, 1909. He volunteered for the service in 1934 and was commissioned in the 22nd Infantry Regiment at Gumbinnen, East Prussia (now Gusev, Russia), in 1936. He was still in the 22nd on November 1, 1943, when he assumed command of the regiment. From 1939 to 1945, he rose from a lieutenant commanding a company to a lieutenant general commanding a corps. In the meantime, he earned the Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords, and Diamonds-mostly on the Eastern Front. He was wounded fourteen times. Tolsdorff assumed command of the 340th Volksgrenadier Division on September 1, 1944, and fought in the Siegfried Line battles. He took charge of the LXXXII Corps on April 1, 1945. After the war, he lived in Wuppertal-Barmen and died in Dortmund on May 5, 1978.

340th Volksgrenadier Division

Col. Theodor Tolsdorff

694, 695, and 696 VG Regiments

340 Artillery Regiment

340 Antitank Battalion

340 Engineer Battalion

(committed in late December at Bastogne under the 1st SS Panzer Corps)

Having absorbed the remnants of another division, the division had more veterans than most, but since it had only recently come from the line near Aachen, it was considerably under strength.

Kampfgruppe Tolsdorff Vilnius

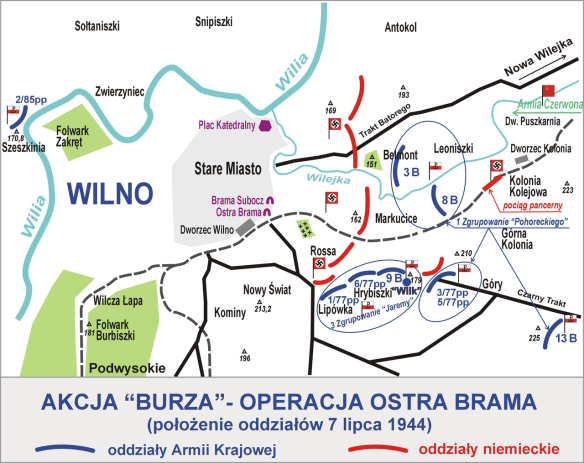

The Home Army intended to use the arrival of the Red Army as an opportunity to seize control of parts of Poland from the Germans, with coordinated uprisings in several cities under the codename Burza (`Tempest’ or `Storm’). In Vilnius, the operation was codenamed Ostra Brama (`Gate of Dawn’), after a famous landmark on the south-east edge of the old heart of the city. Late on 6 July 1944, the Home Army tried to seize Vilnius in an attempt to gain control of the city before the arrival of the Red Army. In the preceding days, the Home Army had effectively secured much of the countryside around the city, but the unexpectedly fast advance of the Soviet forces – about a day ahead of Polish expectations – resulted in Krzyzanowski moving his own timetable forward. Consequently, Krzeszowski had fewer troops at his disposal than he might have wished, and his men were left in possession of only the north-east part of the city. Much of the Polish 77th Infantry Regiment found itself held at arm’s length to the east of Vilnius, its movements further hampered by a German armoured train. Elements of the Polish 85th Infantry Regiment took up positions to the west, beyond the River Vilnia, threatening the German lines of retreat. It is striking that despite years of Soviet and German occupation and tens of thousands of arrests, the AK continued to organise itself into formations that drew their ancestry from the pre-war Polish Army.

Soviet forces arrived outside Vilnius at about the same time that the Poles launched their attack. 35th Guards Tank Brigade, part of General Rotmistrov’s 5th Guards Tank Army, was involved in heavy fighting with the German paratroopers at the airport, from where fighting gradually spread into the city. On 8 July, Krylov’s 5th Army reached the city outskirts, while the Soviet armour gradually encircled the garrison.

It had been General Aleksander Krzyżanowski’s [Polish Home Army] intention to secure the city for Poland before the arrival of the Red Army, but the planners of Burza had always intended that the Poles would cooperate at a tactical level with the Soviets, though they would attempt to set up their own Polish civil authorities before the Red Army could establish pro-Soviet administrations. Unlike in many of the other `fortresses’ that Hitler insisted were defended to the last man, the Vilnius garrison put up a stiff fight, inflicting heavy losses on their opponents. Rotmistrov’s tanks had suffered considerable losses in Minsk, and now found themselves engaged in close-range combat against a determined enemy, equipped with weapons such as the Panzerfaust, that were at their most effective in this environment. Nevertheless, there could be no question of the Germans holding on for long.

Relief was on the way. The rest of 16th Fallschirmjäger Regiment arrived by train near Vilnius early on 9 July, and almost immediately it was assigned to an ad hoc battlegroup, Kampfgruppe Tolsdorff, which went into action outside the western outskirts. Another formation dispatched to try to stem the Soviet flood was 6th Panzer Division, which had been recuperating in Soltau in Germany after suffering heavy casualties earlier in the year. As the men of the panzer division arrived, they were hastily organised into two battlegroups. Gruppe Pössl consisted of a battalion of tanks from the Grossdeutschland division, a battalion of 6th Panzer Division’s panzergrenadiers, and artillery support; it was ordered to advance to make contact with Tolsdorff ‘s group on the outskirts of Vilnius, and thence to link up with the garrison. Gruppe Stahl, with two panzergrenadier battalions and artillery support, would attempt to hold open the line of retreat.

The attack began on 13 July, with Generalleutnant Waldenfels, the commander of 6th Panzer Division, and Generaloberst Georg-Hans Reinhardt, commander of 3rd Panzer Army, accompanying Pössl’s group. The thin screen of Soviet and Polish forces to the west of Vilnius was unable to stop the thrust, which reached Rikantai, about eight miles outside the city. Here, contact was established with Gruppe Tolsdorff, which in turn had a tenuous connection with the Vilnius garrison. During the afternoon, German wounded were evacuated from Vilnius and along the road to the west.

The Soviet response to the German breakout was slow. Late on 13 July, uncoordinated attacks along the narrow escape route were repulsed, but the following day there were several crises as increasingly strong Soviet pincer attacks cut the road repeatedly. Finally, as darkness fell on 14 July, the Germans withdrew to the west. About 5,000 men from the garrison were able to escape, but over 10,000 were lost.

The Soviet authorities proclaimed the liberation of Vilnius on 13 July, but there was still the question of what to do with the Polish Home Army forces that had fought both against the garrison and against Gruppe Tolsdorff to the west of the city. Krzyzanowski and his fellow officers wished to use their men to recreate the pre-war Polish 19th Infantry Division, itself a controversial unit in that it was raised by Poland in the Vilnius region after that area was seized by Poland.

Rudolf Witzig

Witzig’s 1st Battalion of the 21st Parachute Engineer Regiment at Vilnius

The 954 soldiers of the 16th Parachute Regiment entrained for Vilnius, in the south-eastern corner of modern Lithuania, in July. The German High Command considered the defence of Vilnius imperative. If the city fell, it would be impossible to maintain contact between the two German army groups in the Baltic States and to stop the Red Army’s advance towards East Prussia. It had thus been declared a ‘fortress’ city by Hitler and was to be held to the last man. Schirmer’s regiment was subordinated to Field Marshal Model’s Army Group Centre and the Third Panzer Army. Under the direct control of Major General Stahel, an air-defence officer and commander of Vilnius, the 16th Parachute Regiment joined a hotch-potch of units in defence of the city, including the 399th and 1067th Panzergrenadier Regiments, an independent panzergrenadier brigade, the 16th SS Police Regiment, the 2nd Battalion, 240th Field Artillery Regiment, the 256th Anti-Tank Battalion and the 296th Flak Battalion. In addition, elements of the 731st Anti-Tank Detachment, with 25 Hetzer tank destroyers were also available, as well as the 103rd Panzer Brigade with 21 Panther tanks, the 8th Assault Gun Detachment and the 6th Panzer Division with 23 Panzer IV tanks and 26 Panthers.

Poised to advance on the Lithuanian capital were elements of the Soviet 5th and 5th Guards Armies of the Third Belorussian Front. The Soviet attack on the city began on 8 July 1944, with Russian tanks and infantry attacking across Lake Narocz towards the airfield, which was defended by the paratroopers. After bitter fighting, the Soviet 35th Tank Brigade took the airfield. Intense street fighting then commenced as the Soviets attempted to reduce German defences. By midday, the Red Army had fought its way into the city, overrunning the initial line of anti-tank obstacles and destroying a number of the ad hoc German battle groups. The following day, the Germans reported 500 dead and another 500 wounded. By 9 July, Vilnius was encircled. Two days later, the German High Command ordered a break-out. The following night, the defenders broke contact with the enemy and crossed the Vilnia River. Some 2,000 Landsers made it across. With the fall of Vilnius the Wehrmacht’s position in the Baltic States became untenable.

In the meantime, the 16th Parachute Regiment had been followed to the Baltics by Witzig’s 1st Battalion of the 21st Parachute Engineer Regiment, which arrived from France. The battalion, which had an authorized strength of 21 officers and 1,011 other ranks, had been conducting night parachute training at the Salzwedel airbase when it was alerted for movement to Lithuania. ‘By means of a railway movement of several days duration via Berlin and through the peaceful and marvellously sunny summer countryside of Brandenburg and West Prussia and then through East Prussia the battalion reached the border with Lithuania,’ wrote Witzig. ‘The first deployment took place in the Kaunas area.’ Witzig’s battalion reached their planned defensive positions between Schescuppe and Wilkowischen, located only 10 km from the East Prussian border, at the end of July and began to entrench. Within a few days of arriving, the unit was reinforced with an artillery detachment and elements of an assault gun brigade.

Due to the length of the front we were deployed from right to left as follows: Parachute Engineer Battalion, 2nd Battalion, 1st Battalion, and the 3rd Battalion with the 13th Company in reserve and an assault gun brigade [recorded Witzig]. After a while the regiment, which was only equipped with its infantry weapons, received four 75-mm anti-tank guns, which were distributed among the frontline battalions. This position was held the whole of August and September 1944.

Initially the Russians were nowhere in sight. Instead, the men of Witzig’s battalion witnessed the massive westward exodus of Nazi civilian leaders and their families fleeing for their lives to escape the advancing Red Army. The German population in the path of the Russians was thus left leaderless. ‘This was the beginning of the breakdown of law and order,’ remembered Witzig.

After changing positions several times, the battalion finally made contact with the Russians. Witzig’s 3rd Company relieved the 500th SS Parachute Battalion, a punishment battalion:

Only the commander and a few members of the staff had the required rank. All of the company, platoon, and squad leaders were demoted SS officers and NCOs, who wore only an arm badge with their official position. These men had conducted a jump in a coup de main against the headquarters of Yugoslav partisan commander Marshal Tito, only a few weeks earlier. Only with great effort and at the very last moment had he managed to escape.

On the day of their relief, the SS paratroopers bloodily repulsed a Russian tank attack.

On 20 July 1944, a bomb planted at Hitler’s East Prussian headquarters barely missed killing the leader of the Third Reich. In the confusion that followed the attempt, the vast majority of the Wehrmacht’s leaders swore their loyalty to the Führer, while those opposed to the regime were hunted down, cruelly tortured and brutally murdered. A small number committed suicide; only a few survived. Hearing the news at an impromptu parade complete with loudspeakers, Witzig and his men were stunned and felt betrayed. ‘Can you imagine how you would feel if you learned, fighting in the middle of a war, that someone had tried to kill your president?’ one veteran asked the author, when recounting the incident.

But the war went on. According to Witzig, the Red Army attacked his positions about once a week, usually in division strength. Twice Soviet armour, in regimental strength, broke through the German positions:

The majority of tanks, and especially the accompanying infantry, were destroyed by our forward companies in close combat, while the tanks which penetrated deeper were shot by our assault gun brigade. The position was reformed after each attack.

Witzig noted that the Soviets had a large superiority in artillery, which they used liberally. As a result, the terrain surrounding the German defensive positions ‘looked liked the World War I Verdun battlefield’. From time to time the artillery detachment attached to the regiment neutralized a Soviet battery, but it was a losing battle. Nonetheless, Witzig’s battalion, which was deployed as infantry, fought with great determination.

In one particularly hard-fought battle, Witzig’s battalion was mentioned in communiqués for destroying 27 Soviet tanks and stopping the advance of an entire Red Army tank division. On 25 July 1944, the battalion covered a movement to, first, the Kaunas–Daugavpils road and, later in the evening, still further to the north-east to Jonava and entrenched there. ‘A few days ago a strong concentration of enemy tanks was observed and reported in this area,’ reported Witzig, ‘so it was assumed a major attack was imminent.’ The 1st Battalion, 21st Parachute Engineer Regiment, was attached to a battle group commanded by a Colonel Theodor von Tolstorff for this deployment. Tolstorff was, according to Witzig, an excellent officer, and he would win the Swords and Diamonds to the Knight’s Cross the following year as commander of the 340th Volksgrenadier Division.

As had been so often the case, one of Witzig’s companies was detached from the battalion and Witzig was forced to defend with his three remaining companies. The ground on which the battle was fought was open, although the battalion’s flanks were covered by a large forest. The 1st Company, commanded by Lieutenant Kubillus, deployed on the left of the Kaunas–Daugavpils road, while the 2nd Company, commanded by Lieutenant Walther, deployed on the right as it was clear that the Soviets would focus their attacks on this road. Elements of Lieutenant Schürmann’s understrength 4th Company were attached to the 2nd Company, while the remainder served as a battalion reserve. The 3rd Company, commanded by Lieutenant von Albert, was detached from the battalion to serve as a corps reserve in the rear. According to Witzig, several assault and anti-tank guns were deployed with the battalion, located at the edge of a wood and in battle positions in a cornfield, but were not attached to it. The battalion’s own T-mines, stored in stacks of a hundred, had been left in the woods in forward positions. Witzig notes that every squad was equipped with anti-tank weapons of some sort, including at least one Panzerschreck and three to five Panzerfausts.

The Panzerschreck (‘Tank Terror’) or Ofenrohr (‘Stovepipe’) was similar to the American Bazooka rocket-launcher. More than 1.5 metres long and weighing more than 11 kg it was a handful for any soldier to carry, much less use effectively. However, its 88-mm, 3-kg, anti-tank rocket was capable of stopping any Allied tank at ranges of up to 120 metres. The Panzerfaust, on the other hand, was the world’s first truly disposable anti-tank recoilless launcher. Weighing only 6 kg and easy to use, this shoulder-fired launcher shot a hollow-charge anti-tank grenade, which could pierce 200 mm at ranges of 30–80 metres. This was literally point-blank range against a tank and it took a great deal of raw courage, steady nerves and patience to use the weapon effectively. By 1944, both weapons had acquired a fearsome reputation. In the last year of the war, the Allies would find themselves losing hundreds of vehicles a week to the Panzerschreck and Panzerfaust.

During the night of 25/26 July, Witzig’s companies entrenched in fighting positions optimized for anti-tank defence, with two to three men in each position. To defend against surprise attacks, a string of forward outposts had been established, especially in the 1st Company sector. These preparations all took place against a backdrop of the constant sound of Russian tanks moving into place just forward of the battalion’s positions. ‘The defensive position was too exposed,’ complained Witzig, who was convinced that the Russians would attack in strength. The battle began that night, with a combat patrol by the 4th Company, which surprised and captured a Soviet tank crew and a commissar. A short time later, a Russian patrol evened the odds by capturing two outposts of the 2nd Company. Shortly afterwards, a third outpost disappeared. ‘Another outpost was gone,’ remembered Witzig. ‘Only the soldier’s rifle was left in his foxhole.’ The sound of tanks massing continued throughout the night and at the crack of dawn the next day they were visible across a wide front some 1,200 metres from the battalion’s positions.

At the break of dawn on July 26, 1944 the men of the battalion were aware that a day was starting that would demand the greatest efforts from them. With a provoking directness an armada of steel and iron, aware of its superiority, deployed so that even the bravest individual felt depressed. Countless T-34 tanks, artillery pieces and the dreaded ‘Stalin Organ’ [multiple rocket launcher] and assault guns were deployed to break through the defensive positions of the parachute engineers. Yet not one round was fired. There was an uncanny silence on both sides, the calm before the storm.

The silence, however did not last long. ‘And then, flashes from the other side, from thousands of barrels simultaneously’, and shells were pounding the German positions unmercifully: ‘Again and again, pounding, hammering, shattering, pulsating, bursting and cracking,’ recorded Witzig. The incessant barrage lasted for an hour without any reduction in intensity, inflicting numerous casualties on the battalion. As it began to lift, Witzig’s men noticed that the German assault guns had abandoned their battle positions and were nowhere to be seen. But there was nothing that could be done, for the Russian tanks, heavily laden with foot soldiers, were already advancing on the paratroopers through the smoke and the dust with more infantry running alongside the tanks.

Witzig’s men held their fire until the first line of enemy tanks were only twenty metres away, then unleashed a devastating barrage of antitank rounds. At this range, nothing, not even the thickly armoured Josef Stalin tank, was immune from the deadly German volley:

The men of the 1st [Company] took heart and set themselves against this colossus. It came to furious fighting directly on the highway. Lieutenant Fromme fired his Panzerfaust at a T-34 which ground to a halt, engulfed in flames. He himself was wounded. Then Lieutenant Kubillus, the company commander, who had hastened to the highway after realizing the focal point of the attack, went down seriously wounded. Sergeant Weber took command of the company. He himself blew apart three tanks, which stood burning and shattered in front of the company foxholes. Then he saw Sergeants Scheuring, Hüchering and a few other engineers, whom he could not recognize because of the dust and smoke, obliterate another three tanks. Within a short period, the men of the 1st Company, using Panzerfausts and Ofenrohr, had turned fifteen tanks into burning, smouldering iron.

As the enemy tank attack was broken up, leaving dozens of T-34s and Soviet assault guns engulfed in flames, the Russian infantry sprang from their carriers to the ground, intent on making the paratroopers pay. Instead, they were cut down at close range by MG 42s. Caught in the open and without their tanks to suppress the machine guns, the Red Army soldiers were slaughtered. Within minutes, the first Russian attack had collapsed under the massed and accurate anti-tank and machinegun fire of Witzig’s parachute engineers. But the battalion, in turn, suffered heavy losses, with the 1st Company reduced to thirty men.

In the meantime, to the south of the Kaunas–Daugavpils road the 2nd Company, reinforced with the understrength 4th Company, was having a more difficult time containing the Russian assault. A group of some fifty T-34s succeeded in fighting their way through the company positions and cutting off the road behind the two companies. ‘The mounted infantry were taken under fire first and forced to jump off,’ wrote Witzig. ‘Engineer Stauss engaged a tank with his Ofenrohr and suddenly a second tank was also on fire. But the remainder rolled westward without bothering about their infantrymen left behind.’ The German assault guns, which might have defeated the Russian tanks, had already left the battlefield and these had been followed by the surviving anti-tank guns, leaving the paratroopers to fight unsupported. ‘I engaged the tanks which were passing close by my right as the Russians did not attack head on,’ remembered Sergeant Hans-Ulrich Schmidt, from Hamburg, relating his escape in the midst of the advancing Red Army:

After the first echelon passed by, I discovered about five Russian soldiers on every T-34. At the same moment another T-34 showed up about 100 metres to the right of me. I fired one shot with my Ofenrohr and hit it, but after two minutes it began moving and firing again. I charged my Ofenrohr with a second shell immediately as I heard the noise of battle behind me. I tried to establish contact to the right and left of me, but no one had remained in their positions. So I left the position and ran back into the cornfield behind me. Here I found myself between several Russian tanks, which surrounded me. I raised my Ofenrohr, aimed and fired, but the electrical firing trigger failed. One of the tanks discovered me and fired with its gun. I was knocked to the ground by the blast of the shell and hit my forehead against the Ofenrohr. That was my salvation. I pretended to be dead and the tanks moved on. After they were out of sight I ran as fast as I could to the rear, concealed by the cornfield.

By this point in the battle, there were Russian soldiers to the front, on the right flank and behind the battalion’s position. Now it was only a matter of breaking contact with the Soviets as quickly as possible, withdrawing before the battalion could be encircled and annihilated, and regrouping on defensive positions to the west. But the Soviet tanks which had broken through had been followed by masses of Russian infantry, which attacked the German paratroopers as they sought to cross the 2 km of open ground to reach the safety of the forest and cover. Now it was the Russian machine guns which fired unremittingly, mowing down the German paratroopers as they sought to escape. Few made it. Only twelve unwounded survivors of the 1st Company made it to the battalion rally point, along with only ten men from the 2nd Company. Major Witzig led the remnants of his battalion through the forests, bypassing the Soviets and avoiding battle until the survivors reached the German lines.

We set out towards the north under heavy fire along a small trail [remembered Private Anzenhofer]. For some time we strayed through the forest in column formation led by Major Witzig, meeting remnants of the battalion. The commander led us, through Russian tank and crowded troop formations, back to our own lines without further losses. To this day, everyone who survived still gives him credit.

Witzig himself had only praise for his men, especially his medical personnel, as he wrote after the war:

Their sense of duty saved the lives of hundreds of German and Russian soldiers. Only someone who has been in the inferno of death and destruction can measure how these men fought. Selfless and fearless, animated by the thought of helping their wounded comrades, no matter which uniform they were wearing and bringing them back safely as quickly as possible.

Many of the German medics were killed or seriously wounded, while others disappeared, never to be seen again.

Over the course of the next several days, other paratroopers rejoined the battalion, which, according to Witzig’s account, numbered sixty-five men. Witzig used these to establish blocking positions and prevent the Russians from breaking through. This remnant of Witzig’s battalion was committed again and again in a futile attempt to stop the Red Army. By the end of August, the 1st Battalion, 21st Parachute Engineer Regiment, had a total strength of 8 officers and 274 men. Of these, however, only 4 officers and 184 men were frontline soldiers. Karl-Heinz Hammerschlag, who fought under Witzig in Lithuania, remembered that from a battalion of more than 1,000 men in the summer of 1944, only 30 remained by September. ‘We had no tanks, no field artillery, no anti-tank artillery and no Luftwaffe,’ he told the author. ‘We fought mostly with Panzerfausts and anti-tank mines.’