Before that, in September 1601, the Spanish at last struck at what had always been England’s Achilles’ heel in Ireland. Juan del Águila landed with 3,000 troops at Kinsale and a smaller force under Alonso de Ocampo landed at Baltimore. They were about as far away as it was possible to get from rebel-held territory in the north and the idea seems to have been to turn the two ports, already notorious havens for pirates with no regard for English authority, into corsair ports preying on Dutch and English shipping, following the successful example of the felibotes operating out of Dunkirk.

Águila was promptly cut off by sea while Sir George Carew, Lord President of Munster, besieged Kinsale by land. When Tyrone and O’Donnell marched south their forces, joined by Ocampo, were defeated outside Kinsale on Christmas Eve by Charles Blount, Baron Mountjoy, Essex’s competent successor as Lord Deputy of Ireland. Mountjoy had already torn the heart out of the rebellion with an amphibious landing in the north and a scorched earth campaign on Tyrone’s lands.

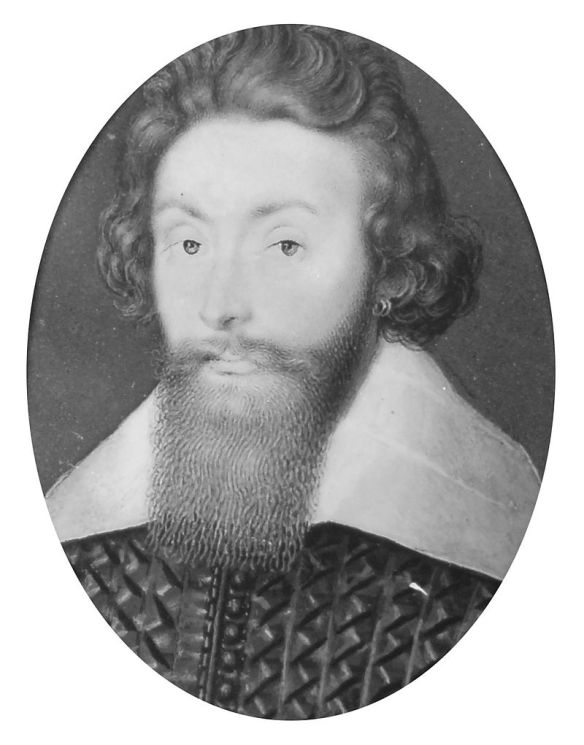

Richard Leveson

The suppression of the rebellion was possible only because the Royal Navy established control of the waters around Ireland for the first time. The naval commander was Sir Richard Leveson, one of a new generation of naval commanders in their early 30s who also included Sir William Monson, author of the multi-volume and occasionally accurate Tracts that gave historian Michael Oppenheim the hook on which to hang the first detailed history of the 1585–1604 war.

Leveson and Monson came the closest of all Elizabeth’s admirals to capturing a silver flota off the Azores during the last fund-raising cruise of her reign, in the summer of 1602. It was supposed to be a combined operation with the Dutch but they were late to the rendezvous in Plymouth. Leveson sailed on ahead with five Royal Navy ships while Monson remained behind with four to wait for the Dutch. Within a few days Monson received an order from the queen to sail immediately, as word had reached London that the flota had reached the Azores.

It had, and sailed on to Lisbon past Leveson, who attacked one of them unsuccessfully. Monson, delayed by malfunctions on his ships, arrived just too late. They found a consolation prize at the Portuguese port of Sesimbra, south of Lisbon, where on 12 June they fought off eleven galleys to capture the large carrack São Valentinho. Her cargo was sold for £44,000, which barely covered the queen’s costs, rapidly rising amid the wholesale corruption and shoddy workmanship presided over by Lord Admiral Howard. ‘If the queen’s ships had been fitted out with care’, Monson wrote, ‘we had made her majesty mistress of more treasure than any of her progenitors ever enjoyed’.

Three of the galleys at Sesimbra had come from Lisbon under the command of Alonso de Bazán, but the other eight were Spinola’s Genoese galleys, which Federico had only just joined in Lisbon to lead on the last part of their voyage to the Netherlands. The galleys had massive 60-pounder cannon in their bows and formed a tight defensive screen in the shallows around São Valentinho.

Monson, who had spent a year as a slave on one Bazán’s galleys, anchored outside their effective range and bombarded them with the 16 culverins on Garland to force them to break formation. When Bazán’s galleys did, the shallow draft Dreadnought (360 tons to Garland’s 532) sailed into the gap and took them on at close range with her 11 demi-culverins and 10 sakers. After Bazán was badly wounded his battered galleys rowed away, but Spinola stayed and fought until he had lost two and the rest were in imminent danger of sharing their fate.

Spinola took his six remaining galleys back to Lisbon and with royal consent took oars and rowers from Bazán’s galleys. On 9 August the galleys departed, carrying 36 pay chests for the army in Flanders. At Santander he took on a further 400 troops to complete an on-board tercio of 1,600 men and reached Port-Blavet in Brittany by mid-September. This time there was no armada to distract attention: the English and Dutch were well informed of his movements and they were ready for him.

Off Dungeness during the night of 3–4 October Spinola ran into the 400-ton Hope, launched in 1559 and along with Victory the last unreconstructed carrack in the Royal Navy. She was the flagship of 29-year-old Sir Robert Mansell, one of the Lord Admiral’s placemen of whom Julian Corbett wrote the damning verdict that ‘it is the rise of this man that marks the commencement of a reign of selfishness and corruption that almost brought the navy to ruin in the next reign’. Mansell had little naval experience but his excellent flag captain anticipated that Spinola would try to repeat his 1599 tactic of sailing close to the English coast. The carrack savaged San Felipe before the other five galleys came up in support, and followed them until they rowed over the Goodwin Sands.

When they made a break for the Flemish coast the Dutch inshore squadron was waiting for them and sank San Felipe and Lucera by ramming. Padilla escaped to Calais, where the French interned her and used her as firewood. San Juan and Jacinto made it inside the Flanders Bank but were too badly damaged and their rowers too exhausted to do more than run aground near Nieuport. Only Spinola on San Luis, carrying the 36 pay chests, managed to row to safety in Dunkirk.

Queen Elizabeth died on 24 March 1603 and Federico Spinola survived her by barely two months. Having brought his Sluys squadron back up to its eight-galley strength, he sortied on 26 May to attack three Dutch oared ships, including Black Galley, which were accompanied by the 34-gun cromster Gouden Leeuw (Golden Lion). Spinola, standing on the forecastle as his galley led the charge against Black Galley, had an arm shot off and was hit in the stomach by swivel guns, after which his men lost heart and rowed back to Sluys.

Sir Walter Ralegh and George Clifford, Earl of Cumberland, spanned the gap between the wholly royal and wholly private naval expeditions during the latter years of Elizabeth’s reign. As such they represent the (not very close) English equivalent to the Spinolas as men so indebted or devoted to their monarch that they spent their own fortunes in her service. Ralegh was a parvenu whose fortune came entirely from the favour Elizabeth had shown him. The Barons de Clifford were an old established northern borderer dynasty, but the earldom of Cumberland was created for Clifford’s grandfather by Henry VIII as a reward for the family’s dog-like loyalty to the Tudors.

Posterity exalted Ralegh, mainly because, thanks to his Roanoke venture, he was seen as the prophet of the British Empire, but also because his five-volume History of the World, written when imprisoned in the Tower under sentence of death, was an intellectual tour de force that put him on a par with Sir Francis Bacon as the most influential English author of the 17th century. I cannot improve on the conclusion of his Dictionary of National Biography entry:

Those who came after him, who never met him, have instinctively liked Ralegh, or their version of Ralegh. He was certainly a most astonishing and compelling man, in his writings as in the rest of his life touched by genius and greatness, the focus of legend. It should not be forgotten, however, that many of those who lived in the same small world of the Elizabethan court, after long association with Ralegh, either disliked him intensely or distrusted him profoundly.

Cumberland’s loyalty was sparingly rewarded and mercilessly exploited by Elizabeth. He began to lose his hair early and was not particularly good-looking, but the biggest obstacle between him and the royal favour that cascaded on prettier men may have been that he was too awkward to indulge convincingly in the artifices of courtly love. He was also an inveterate gambler, and although granted the ceremonial role of Queen’s Champion in 1590, Elizabeth never gave him a military command or admitted him to the Privy Council. His best-known portrait, a 1590 miniature by Nicholas Hilliard, shows a man dressed in extravagant jousting armour with the queen’s jewelled glove pinned to a feathered hat that makes the whole ensemble seem rather ridiculous.

Both men were among the foremost promoters of the corsair war, but neither was solely motivated by the prospect – in Cumberland’s case the urgent need – of profit. We have seen Ralegh’s attempt to set up an operational base in Virginia from which to interdict the Spanish flotas, and Cumberland adjusted his ventures to supplement the Royal Navy’s attempt to blockade the Spanish coast, thereby saving Lord Thomas Howard from disaster at Flores in 1591. Of course both hoped for wealth as well as glory, but they would probably have achieved more of the former if they had not also wished to perform some outstanding service in the hope of tangible recognition by the queen.

Both of them built giant galleons that could not possibly pay their way simply as corsairs and must have been intended to supplement the Royal Navy. Ralegh, as we have seen, was relieved of the expense of his Ark, which became Lord Admiral Howard’s flagship. In 1595 Cumberland built an even bigger (600 tons burden) ship named Malice Scourge at the queen’s suggestion. In it he led, brilliantly, the largest entirely private military-strategic operation of Elizabeth’s reign to take San Juan, Puerto Rico, three years after Drake had failed to do so during his last voyage.

It did nothing to change Elizabeth’s opinion of him and after 1598 he was compelled to sell off his fleet. Malice Scourge, renamed Red Dragon, became the flagship of the new East India Company in 1600. Rather pathetically Cumberland tried to console himself with the thought that ‘I have done unto her Majesty an excellent service and discharged that duty which I owe to my country so far as that, whensoever God shall call me out of this wretched world, I shall die with assurance I have discharged a good part I was born for’.

He spent less time at court, curtailed his gambling and devoted his last years to salvaging some of the lands he regretted having ‘cast into the sea’. He also made himself useful to James VI of Scotland and, despite having been among those who condemned James’s mother to death, was finally made a privy councillor when the king became James I of England. Cumberland died in 1605.

Ralegh’s meteoric career stalled after he got with child and secretly married Bess Throckmorton, one of Elizabeth’s ladies in waiting. When the truth emerged in April 1592, after the birth of the child, the queen was incandescent. Husband and wife were put under separate house arrests, but after Ralegh grossly misjudged the situation and indulged in some insultingly theatrical expressions of contrition the queen had them both consigned to the Tower. He was let out a month later to salvage what he could of the queen’s share of the richest single prize taken during her reign.

This was the great Portuguese East Indies carrack Madre de Deus. According to the results of an ‘exquisite survey’ given in Hakluyt, she was about 1,450 tons burden and in excess of 2,000 tons fully laden. The model in the Lisbon Museu de Marinha confirms she had a two-storey forecastle and a staggered three-storey sterncastle. With 32 guns, 10 of them sakers or larger firing through main deck gunports, and a complement of 600–700 men, she was a formidable challenge.

How Madre de Deus was taken and what followed provides a suitable microcosm through which to explain the corrosive failure of public–private ventures in the English guerre de course. Three groups met by chance off Flores in the Azores. With the scandal of his secret marriage hanging over his head, Ralegh made a desperate effort to put together an expedition involving the ever-popular queen’s ship Foresight (295) under Robert Crosse. The private component was Ralegh’s own Roebuck (240) under Sir John Burgh, John Hawkins’s Dainty (200) under Thomas Thompson, Bark Bond (56) sent by John Bond and partners of Weymouth under Nicholas Ayers (the previous Bark Bond had been used as a fireship in 1588), and a number of pinnaces and frigates.

Ralegh tried to get away on 6 May but, blown back, he was superseded a week later at the queen’s command by Sir Martin Frobisher in Garland (532) and recalled to London. Frobisher may have been accompanied by some unnamed ships grudgingly sent by London merchants in response to the conditional release by the queen of £6,000 on the money due to them for prizes taken by the London squadron in 1591. This was something new: the queen was not only retaining the proceeds of her subjects’ ventures as a forced interest-free loan, but was also using it to tell them what to do.

The objective was to intercept five East Indies carracks expected at the Azores in July. Ralegh intended to lead the whole flotilla to the Azores, but Frobisher brought with him instructions for the main component to sail with him to Cape St Vincent while a smaller group under Burgh patrolled the Azores. Frobisher was not one to question orders, but Crosse on Foresight and Thompson on Dainty knew it was folly to divide the command and slipped away to join Burgh’s Roebuck.

Cumberland’s ships made up the second component, led by John Norton in Tiger (170), followed by Abraham Cocke in Sampson (260), Phoenix (60), the frigate Discovery (12) and two other small ships, Grace of Dover and Bark of Barnstaple. Gold Noble (200), owned by the London merchants John Bird and John Newton, was supposed to sail with them but became separated and sailed instead to the coast of Portugal, where it took a 900-ton (presumably ‘tons and tonnage’) prize.

The third component was two ships returning from an already highly successful West Indies voyage, in which they raided San José de Ocoa and captured Yaguana on Hispaniola, and then cut a prize out from under the guns of the fort at Trujillo and captured Puerto Caballos in Honduras. The syndicate that sent the expedition was headed by John More and included John Newton (again), Robert Cobb and Henry Cletherow, all of London. It was led by Christopher Newport in Golden Dragon (130) followed by Hugh Merrick in Prudence (70). Golden Dragon carried two demi-culverins, six sakers, seven minions and four falcons. She had a crew of 70–80 men with 31 muskets and three arquebuses.

Burgh arrived at Flores on 21 June to learn that he had missed the first of the East Indies carracks, which also slipped past Frobisher during the night of 7–8 July. Immediately afterwards Burgh sighted Santa Cruz, pursued by Cumberland’s ships. In a dead calm he rowed to examine the carrack, intending to board her next day, but during the night a storm came up and she ran herself aground, where her crew were seen frenziedly unloading the carrack before setting her on fire. Burgh and Norton sent a landing party that routed the Portuguese and captured some of the cargo, as well as the ship’s purser, who was coerced into admitting that three more carracks were 15 days behind. He did not know that two of them had already wrecked.

When Newport arrived he agreed to ‘consortship’ with Burgh, but Norton refused to acknowledge that Burgh’s commission from the queen had seniority over his own from Cumberland. Despite this, the two agreed to act in concert and stationed their ships in a screen west of Flores, each ship spaced about 6 miles/10 kilometres from the other on a south–north axis. From the southern (windward) flank the sequence was Dainty, Golden Dragon, Roebuck, Tiger, Sampson, Prudence and Foresight.

In the morning of 3 August Dainty sighted Madre de Deus and attacked her at about midday, followed at two-hour intervals by Golden Dragon and then Roebuck, joined by Foresight – which was either out of station or sailed past Cumberland’s ships and Prudence – at about 7pm. Dainty had her foremast shot away and lost contact for five days. Burgh and Crosse, desperate to prevent the carrack running herself aground, crashed Dainty and Foresight into her, under her main deck guns, and disabled her by cutting the bow rigging.

After that it was a pell-mell night assault with the crews of Golden Dragon, Sampson and Tiger pouring aboard alongside the men of Foresight and Dainty in a looting frenzy that nearly resulted in the loss of the ship and all aboard her, as recounted by Purchas: ‘The English now hunted after nothing but pillage, each man lighting a candle, the negligence of which fired a cabin in which were six hundred cartridges of powder’.

There never has been honour among thieves. When Thompson’s Dainty rejoined he asked Burgh for a share of the silks, jewels and coins that now filled the cabins of the other captains. Burgh gave him a seaman’s chest that had already been broken open. Norton, who had promised the Portuguese captain that his passengers would not be personally robbed, kept his word and gave them Grace of Dover to take them to Flores. But Nicholas Ayers on Bark Bond intercepted the pinnace and stripped them naked, collecting hundreds of diamonds, rubies and pearls sewn into their clothing.

The extent of the preliminary looting can be judged from the fact that Madre de Deus drew 31 feet when she left Cochin but only 26 when she sailed into Dartmouth harbour on 9 September. There, theft on an industrial scale began with two thousand buyers flocking to the port. When it became apparent that Sir Francis Drake, vice-admiral of Devon and Cornwall, and the other queen’s commissioners were taking a decidedly broad view of this, Burghley sent his son Robert Cecil to try to stop the carrack being emptied of all her contents. He reported from Exeter that everyone he met within 7 miles/11 kilometres of the city smelled strongly of pepper, cloves and other spices.

Finally the queen ordered the release of Ralegh from the Tower to recover whatever he could. He managed to have what was left of the bulkier goods to the value of £141,200 loaded on Garland and Roebuck for transport to London. Elizabeth, whose investment had been a mere £3,000, tried to claim all of it, ‘challenging the services of her subjects’ ships, which are bound to help her at sea’. The Lord Admiral, anxious to preserve the income from his tenth, persuaded her that ‘it were utterly to overthrow all service if due regard were not had of my Lord of Cumberland and Sir Walter Ralegh and the rest of the adventurers, who would never be induced further to venture’.

The point being that the looting had cost the ship owners, promoters and suppliers – who were entitled to two-thirds of the value of the prize – far more than it had diminished the Lord Admiral’s tenth and the twentieth due to the queen for customs duties. Nonetheless she took the lion’s share of the remainder, arguing that the sailors had already taken much more than they were entitled to and that the adventurers must recover what they could from their ships’ crews. Cumberland’s syndicate was allowed £37,000, with which he was deeply unhappy but which gave them all a reasonable return. Ralegh and his partners were allowed only £24,000, which was a stinging slap in the face. Against this he had earned the queen’s forgiveness, which he must have considered worth the price. But he was still banned from the court until 1597, and never recovered her favour.

The conclusion to be drawn from this episode is obvious. Elizabeth’s public–private ventures did severe damage to the subjects of King Philip II and on occasion caused the Spanish monarch acute financial embarrassment. However, she herself gained much less from those ventures than she might have done because she presided over a kleptocratic state and was herself guilty of dishonest dealing. Majesty is the first casualty when a monarch descends to squabbling with her subjects over the division of loot, and it’s perfectly clear that it was not just her increasing age that caused Elizabeth’s moral authority to drain away during the last decade of her reign.