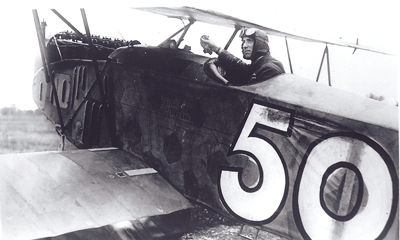

Colonel Barker, VC, in one of the captured German airplanes against which he fought his last battle.

As the Germans fell back step by step early in October 1918, much of the Allied air effort was devoted to attacks on road junctions, railway stations and other bottlenecks. The German Flying Corps continued to fight fiercely, if spasmodically, and to inflict losses on the Allied day bombers, although in doing so their own losses were far from light.

On 1 October, for instance, DH9s of No 108 Squadron had just attacked Ingelmunster station when they were intercepted by thirty-three enemy scouts. A running fight developed, and in the next ten minutes, during which the DH9s managed to stay in close formation, they shot down four of the enemy without loss.

During the first week in October the two Australian fighter squadrons, No 2 with its SE5s and No 4 with its Camels, were very active, carrying out many ground-attack sorties against enemy airfields and lines of communication. No 4 Squadron in particular received several mentions in the official communiqués, beginning on 2 October:

‘Lieutenants O. B. Ramsay and C. V. Ryrie, 4 Squadron AFC, left the ground at 4.45 am to attack Don Railway Station, where they dropped four 25-lb bombs, observing one direct hit; they then dropped four more bombs on Houplin Aerodrome and fired at machines and mechanics on the Aerodrome from 700 feet. A train steaming out of Haubourdin was also fired at and made to pull up.’

Then, on 5 October:

‘A patrol of 4 Squadron AFC, consisting of Captain R. King, 2nd Lieutenant T. H. Barkell and 2nd Lieutenant A. J. Palliser, during a flight of 1 hour 20 minutes, carried out the following work: Destroyed one balloon in flames; dropped twelve 25-lb bombs from a low height on a train in Avelin Station and on the Aerodrome, obtaining four direct hits on the station and one on a shed on the aerodrome. They also fired a large number of rounds into a “flaming onion” battery, and three times attacked horse transport, which scattered in confusion. The sheds on Avelin Aerodrome were also shot up, and finally a train was fired at, one wagon of which exploded, completely wrecking two trucks.’

In October a new German scout, the Fokker D.VIII, appeared at the front in small numbers. It was developed from the Fokker E.V, which had been assigned to Jasta 6 for operational trials in July but which had been withdrawn after three crashes involving structural failure of the wing. Imperfect timber and faulty manufacturing methods were found to have been the cause, and in September production was started again, the type now bearing the designation Fokker D.VIII. A parasol monoplane, the D.VIII was more manoeuvrable than the D.VII biplane and had a better operational ceiling, although it was slightly slower. Only about ninety had been delivered by the end of the war and, although its pilots reported that it handled well, it had little chance to prove itself in action.

With the end of the war in sight, and enemy aircraft absent from the front for lengthy periods, the leading Allied fighter pilots flew intensively, keen on adding to their scores. By the end of October, Eddie Rickenbacker of the 94th Aero Squadron had scored twenty-six victories, putting him well ahead of any other American pilot; the next in line was Captain W. C. Lambert of the RAF, with twenty-two, followed by Captain A. T. Iaccaci (RAF) and Frank Luke with eighteen, Captain F. W. Gillet (RAF) and Raoul Lufbery with seventeen, then Captains H. A. Kuhlberg and O. J. Rose (both RAF) with sixteen each. Rickenbacker survived the war to receive the Congressional Medal of Honor. After the war he was active in both the automobile and airline industries and was largely responsible for building up Eastern Airlines, of which he became chairman in 1953. During the Second World War he toured widely, visiting USAF units overseas. In one flight across the Pacific his aircraft had to ditch, and he and his crew spent twenty-one days on a life-raft before being rescued. He remained active in various fields until his death in July 1973, at the age of eighty-two.

In the Cigognes, René Fonck scored his sixty-eighth and sixty-ninth victories on 5 October. There was no one to come near him now, but sightings of enemy aircraft were so infrequent that it would be the end of the month before he scored again.

Meanwhile, in the north, the RAF took its latest fighter, the Sopwith Snipe, into action during these final weeks. No 43 Squadron had begun offensive patrols with its new Snipes on 26 September; these mostly involved bomber escort or diversionary patrols in conjunction with bombing raids, and in six days the pilots claimed the destruction of ten enemy aircraft for no loss. Unfortunately, only two of the enemy machines could be confirmed, these being credited to Lieutenants E. Mulcair and R. S. Johnston. Throughout October No 43 continued to fly escort missions, often with the DH9s of Nos 98 and 107 Squadrons. On occasions the Snipe pilots would also indulge in some bombing; on 23 October, for example, they obtained several direct hits with 20-lb Cooper bombs – four of which could be carried beneath the Snipe’s fuselage – on the railway station at Hirson.

In October a second unit, No 4 Squadron Australian Flying Corps, also began to exchange its Camels for Snipes at Serny. The first patrol with the new aircraft was flown on the 26th, when nine Snipes led by Lieutenants T. C. R. Baker and T. H. Barkell ran into fifteen Fokker D.VIIs over Tournai. Barkell, although wounded in the leg, shot down two of the enemy, while Lieutenants Baker, E. J. Richards and H. W. Ross got one each. On the following day the Squadron lost Lieutenant F. Howard, shot down and killed in a dogfight over the same area.

The next three days saw some of the greatest air battles of the war as the German Flying Corps threw its dwindling reserves into action against the Allied aircraft that were now swarming everywhere behind the enemy lines. On 28 October, fifteen Snipes of No 4 Squadron AFC, led by Captain A. T. Cole, came upon twelve Fokker D.VIIs which were attacking a formation of DH9s over Peruwelz and destroyed five of the enemy for no loss. Later in the day, ten Snipes under Captain R. King were detailed to escort twelve SE5as of No 2 Squadron AFC in a bombing attack on Lessines, north of Ath on the Dendre river. The SEs carried out their bombing attack and then climbed to join the Snipes, which were engaging about thirty Fokkers. By the time the SEs arrived the fight was virtually over; two of the Fokkers had been destroyed by Lieutenant A. J. Palliser, a third by Major W. A. McLaughry and a fourth by Lieutenant T. C. R. Baker, who had already shot down a D.VII while out on patrol by himself that morning. Another Fokker was destroyed by Lieutenant E. L. Simonson of No 2 Squadron, who shot the enemy off a Snipe’s tail.

In the afternoon of 29 October, fifteen Snipes of No 4 Squadron in two flights under King and Baker were patrolling near Tournai in fine but hazy weather when they encountered an equal number of Fokker D.VIIs at 14,000 feet. Conscious that there were other strong formations of Fokkers in the area – probably sixty aircraft in all – the Australians quickly engaged the first gaggle, which were apparently preparing to attack some Allied two-seaters lower down. A fierce battle ensued, during which two Fokkers were shot down in flames by Lieutenant G. Jones. Two more were destroyed by Lieutenant Palliser, while Lieutenants Baker, P. J. Sims, O. Lamplough and H. W. Ross accounted for one each. Unfortunately, Sims failed to return from this fight.

On 30 October, the bomb-carrying SE5as of No 2 Squadron AFC joined other aircraft in an attack on Rebaix airfield. The bombs were dropped from a very low altitude – sometimes as low as twenty feet – destroying several hangars and buildings as well as three LVG two-seaters parked nearby. The raid was escorted by eleven Snipes of No 4 Squadron, but no enemy aircraft were sighted.

There followed a spell of poor weather which finally broke on 4 November, when No 2 Squadron AFC formed part of a force that carried out a highly successful attack on Wattines airfield. The raid, which was escorted by No 4 Squadron AFC and the Bristol Fighters of No 88 Squadron RAF, was hotly contested by the enemy, and in the running battle that developed six Fokkers were shot down. But it was a bad day for No 4 Squadron: Lieutenant Goodson was hit by anti-aircraft fire, crashing into the canal at Tournai, and Lieutenant C. W. Rhodes was shot down in combat, both airmen surviving to become prisoners. They were luckier than Captain T. C. R. Baker and Lieutenants Palliser and P. W. Symons, all of whom were shot down and killed.

It was a hard loss for the Australians to bear, with the end so near. The Germans were now in full retreat from the Scheldt, and in the days that followed both Australian squadrons were engaged in attacks on enemy forces near Ghislenghien, rolling stock at Enghien and on Croisette airfield. No opposition was encountered in the air, and so the Snipes of No 4 Squadron came down to join the SEs in strafing attacks. The last offensive sortie by the Australian Snipes was carried out on 10 November, when enemy columns were strafed in the Enghien area.

The sturdy Snipe had fulfilled all its expectations in the hands of the Australians; but it was the extraordinary exploit of a Canadian pilot, Major W. G. Barker, that was to enshrine the fighter in aviation history during those last weeks of the war.

Bill Barker had arrived in France in 1915 with the Canadian Mounted Rifles, and after spending his twenty-first birthday in the mud of Flanders had applied for a transfer to the RFC. Accepted as an air gunner with the lowly rank of Air Mechanic, he had been posted to No 9 Squadron RFC, which in the closing months of 1915 was flying BE2c observation aircraft from Allonville. He was an expert shot, having hunted elk from horseback as a boy, and his skill was rewarded when he destroyed a Fokker monoplane that attacked his BE behind the enemy lines.

Early in 1916, Barker was commissioned and posted to No 4 Squadron RFC, which also flew BEs, as an observer. After taking part in the air operations over the Somme, during which he was slightly wounded in a skirmish with an enemy fighter, he applied for pilot training in the autumn of 1916. He was awarded his pilot’s brevet in January 1917 and posted as a captain to No 15 Squadron, flying on artillery spotting duties. He survived the bloody fighting of 1917 and was awarded the Military Cross; in September he was posted to No 28 Squadron, which took its Sopwith Camels to France in October. He was given command of ‘C’ Flight, and adopted Sopwith Camel serial number B6313 as his ‘personal’ aircraft. Together, pilot and machine were to make a formidable team.

His first victory with No 28 Squadron came on 20 October 1917, when he shot down an Albatros near Roulers. This was followed, six days later, by two more. These were Barker’s last victories in France for the time being, for in November No 28 Squadron was sent to the southern front as part of the Allied effort to bolster the Italians, who had suffered a series of reverses in their campaign against the Austrians. When Barker went to Italy, so did his faithful B6313.

Barker shot down an Albatros on 29 November and another on 3 December, the first of nine victories he was to score with No 28 Squadron on the Italian Front. On 8 March 1918 B6313 was damaged when it crash-landed in mist at Asolo, but it was flying again a week later and Barker celebrated the Camel’s return to action by destroying an Albatros D.III at Villanova on 18 March, followed by another near Cismon the next day.

On 10 April 1918 he was posted to command No 66 Squadron at San Pietro, and once again he took B6313 with him. By 13 July his score stood at twenty eight enemy aircraft and four observation balloons destroyed. One of his victims during this period was Oberleutnant Frank Linke-Crawford, the third-ranking Austrian ace with thirty victories.

On 14 July 1918 Barker was promoted Major and given command of No 139 Squadron, which was then flying Bristol Fighters at Villaverla. Once again, his Camel went with him; to keep the paperwork straight, it was officially transferred to ‘Z’ Aircraft Park, which was a maintenance unit, and attached to No 139 Squadron. Barker had it painted in the markings of No 139: multiple narrow white stripes applied vertically between the fuselage roundel and the tailplane.

Although Barker flew Bristol Fighters on some occasions, he usually accompanied the two-seaters in his B6313, and while flying this aircraft he destroyed six more enemy machines, the last on 18 September 1918 over the Piave front. The useful life of B6313 was now coming to an end; the Camel had already been re-engined several times, and its airframe was showing dangerous signs of wear and tear. Accordingly, the commander of the RAF contingent in Italy, Colonel P. B. Joubert de la Ferté (later Air Chief Marshal Sir Philip Joubert de la Ferté kcb, cmg, dso), directed that the aircraft be dismantled and the pieces placed in storage for spares; Major Barker was to be allowed to take any souvenirs he wished. As a long-standing fighting partnership between one man and one aircraft, it was probably unique.

At the beginning of October 1918 Barker returned to the United Kingdom and was posted to No 201 Squadron at La Targette. The Squadron was then still equipped with Sopwith Camels, but was due to receive Snipes in the near future. One Snipe, serial E8102, was allocated to Barker for use in the Squadron; his overall brief was to test the aircraft to the fullest extent in action and to develop new air fighting techniques.

By the time he joined No 201 Squadron, Barker’s score of aircraft destroyed stood at forty-six. His decorations included the DSO and Bar, MC and two Bars, the Croix de Guerre and the Italian Cross of Valour. He was just twenty-four years old.

Barker’s time with No 201 Squadron, however, was short-lived, amounting to little more than a refresher course, and in the last days of October he was ordered back home to take up a new and safer posting as CO of a flying school at Hounslow in Middlesex. On the morning of the 27th, he took off from La Targette for the last time and set course westwards towards the English Channel.

Suddenly, as he cruised high over the Forêt de Mormal, something caught his attention: a flicker in the sky, several thousand feet higher up. It was the wing of a turning aircraft, glittering in the sun, and Barker knew that in this area the chances were that it was a Hun. He decided to climb up and investigate.

The strange aircraft turned out to be a Hannoveraner two-seat observation aircraft, flying at 21,000 feet. At this altitude, which was well above the normal patrol level, its crew possibly thought that they were immune from attack. Nevertheless, the enemy observer was wide awake, and put a burst of Spandau bullets through the Snipe’s wing as Barker closed in to make his attack. The Canadian fired back and saw his bullets strike home, but the Hannoveraner flew steadily on. Twice more the Canadian closed in, exchanging bursts of fire with the enemy gunner. Both aircraft were hit repeatedly. Suddenly, Barker decided to change his tactics. Long ago, he had removed the conventional radial sight from his twin Vickers machine-guns and replaced it with a simple peep sight, which he claimed was more accurate. He now concentrated on hitting the German gunner, and after a burst or two saw the man throw up his arms and collapse in the cockpit.

The German aircraft was defenceless now, and Barker closed in to finish it off from point-blank range. After a few moments it broke up, its fuselage spinning down towards the forest and its wings drifting in the air. It was Barker’s forty-seventh victory.

Elated, he did not see the Fokker D.VII coming up under his tail. The first indication of its presence came with a confused sensation of whiplash cracks as bullets spattered his aircraft, followed by a spasm of searing pain as one of them tore into his right thigh. The Snipe fell into a spin which Barker corrected by instinct, half dazed with the shock of his wound. Looking round, he found that he had dropped into the middle of a formation of about fifteen more Fokkers and immediately flung his Snipe into a steep turn, loosing off an inconclusive burst at an aircraft that flashed across his nose. He fired at a second, again with no apparent result, but almost at once found himself on the tail of a third.

This time there was no mistake. There was a short burst from Barker’s guns and the Fokker trailed a short stream of white fuel vapour before bursting into flames and rolling earthwards in a ball of fire.

By this time, the Germans were queueing up for a shot at Barker’s twisting aircraft. Bullets crackled around his ears and ripped savagely through the Snipe’s wings and fuselage. Two Fokkers attacked simultaneously from behind. Barker throttled back and hammered one of them as it flashed past, seeing part of the enemy’s tail break away. Then another Fokker came up from below and fired a burst into the underside of the Snipe. Bullets shattered Barker’s left leg and he blacked out. The Snipe nosed over into a dive, and the rush of icy air brought the pilot round. At 12,000 feet he managed to pull the aircraft out of its plunge.

The Snipe creaked and groaned alarmingly, and smoke poured from its overworked engine. When another Fokker came at him head-on, Barker, thinking that his aircraft was on fire, weak as he was through loss of blood and with both his legs smashed, made up his mind to ram it. Then, almost at the last moment, he saw an opportunity and opened fire. The Fokker disintegrated in a cloud of fragments and Barker flew unscathed through its floating wreckage.

Suddenly, Barker realized that his left arm was useless. Looking down, he saw that his sleeve was soaked with blood; a bullet had shattered his elbow. For the second time in this incredible, one-sided battle, Barker fainted.

Again, it was the rush of slipstream that brought him to his senses. Pulling out of the dive, he saw his avenue of escape cut off by eight more Fokkers, which split up to attack him from several directions. One Fokker made a fatal mistake and turned in front of him; Barker’s guns chattered again and the enemy aircraft went down to crash. Resigned now to the fact that he was going to be shot down by the others, he fired his remaining ammunition at them. Miraculously, they broke off the action and flew away eastwards.

Barker, his strength failing rapidly, dived to within a few feet of the ground. Both his legs and his left arm were completely useless, preventing him from using the rudder bar. Somehow, he managed to keep a firm grip on the control column as the tattered, smoking, oil-slicked wreck of the Snipe sank lower. Finally, the wheels struck the ground with a jarring crash; the Snipe bounced into the air and fell on its back. By some miracle it failed to catch fire.

The aircraft had crashed near some British observation balloons, whose ground crews pulled him barely alive from the wreckage. He was taken to Rouen hospital and was still there, deeply unconscious and fighting for his life, when the Armistice came. He eventually went on to make a full recovery, and to receive one of the best-earned Victoria Crosses in the history of air warfare. Sadly, he was killed while working as a test pilot in 1930, at the age of thirty-six.

While Barker lay in hospital, the war entered its last days. After 4 November, a day of intense air fighting, the RAF’s daily summaries noted that enemy air activity was slight; sometimes it was absent altogether. Officially, between 4 and 11 November, the RAF claimed sixty-eight enemy aircraft destroyed and twenty-four ‘driven down out of control’ for the loss of sixty of its own.

In the last hours of the war, the weather was fair but misty. During the night of 10/11 November, No 214 Squadron’s Handley Page 0/400s dropped 112 bombs on Louvain railway sidings, the crews reporting many direct hits. Some of the bombs hit an ammunition train, causing explosions and fires all over the sidings.

At 11.45 am on 11 November, an RE8 observation aircraft of No 15 Squadron touched down at Auchy. Its crew, Captains H. L. Tracy and S. F. Davison, reported that no enemy aircraft had been seen; British troops were in Mons, where the British Expeditionary Force’s long retreat had started more than four years earlier, and enemy AA fire was nil.

On the Western Front, at last, all was quiet.