28 December 1943

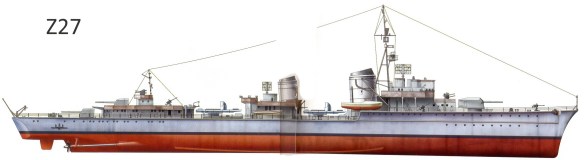

After the invasion of the Soviet Union severed German land access to strategic raw materials such as rubber and tin, blockade runners became essential to the Axis war effort, and the Kriegsmarine maintained destroyers and fleet torpedo boats on the French Biscay coast to escort blockade runners into port during the dangerous final leg of their voyage. On December 27, 1943, two German flotillas sortied to meet the blockade runner Alsterufer, not realizing that Allied aircraft had surprised and sunk it the day before. The German units were the 8th Destroyer Flotilla (Kapitän zur See Hans Erdmenger) with the Z27, Z23, Z24, Z32, Z37 and the 4th Torpedo Boat Flotilla (Korvettenkapitän Franz Kohlauf ) with the T23, T22, T24, T25, T26, and T27. Two British light cruisers, the Glasgow and Enterprise, which had been hunting the Alsterufer, were south of the Germans, and, learning of their mission from signals intelligence, they steered to intercept.

The German flotillas united just after noon on December 28 and swept eastwardly. It was a rough day in the Bay of Biscay with a strong easterly wind. Conditions were difficult aboard the German Type 36A destroyers, which were poor sea boats, and they were worse for the torpedo boats, which had green seas breaking over their bows and spray inundating their bridges.

At 1:32 p. m., the Glasgow spotted the Germans, and eight minutes later, the Z23 saw the British cruisers bearing down. At this point, the Germans were steaming south-by-southeast in three columns. Almost immediately, Erdmenger ordered a torpedo attack, which was impractical due to the range and rough seas. Meanwhile, the British closed, and at 1:46 p. m., Glasgow’s forward turret fired the first salvo from a range of 18,000 yards.

Initially both forces ran south-southeast trading long-range broadsides. At 1:56 p. m., Erdmenger ordered another torpedo attack, and the Z32, Z37, and Z34 took station to port and edged toward the cruisers. At 2:05 p. m., a shell from the Z32 struck the Glasgow, killing two men. At 2:15 p. m., the Z37 fired four torpedoes from 14,000 yards.

While this futile barrage churned through seven miles of stormy water, Erdmenger decided to divide his force, even though German shooting had been at least as good as the British. At 2:19 p. m., the T26, T22, T25, Z27, and Z23 turned north as Z32, Z37, Z24, T23, T24, and T27 continued southeast. The Z27 turned toward the British rather than away, and the flagship became the first German vessel damaged when a 6-inch shell from the Enterprise penetrated a boiler room and ignited a huge fire.

As the Germans divided, the Glasgow joined Enterprise and ranged its turrets on the three torpedo boats heading north. At 2:54 p. m., the Glasgow damaged the rear warship, the T25. Then the Glasgow shifted fire to the T26 and hit its boiler room.

After temporarily disengaging to clear some gun defects, the Enterprise joined the Glasgow, and the two cruisers sank the T26, the most southerly of the three damaged ships at 4:20 p. m. The Enterprise dispatched the T25 at 4:37 p. m. with a single torpedo. Finally, the Glasgow found the Z27 drifting with all guns silent. It closed and exploded the German destroyer’s magazines at 4:41 p. m. The British cruisers then made for Plymouth. The Glasgow had been hit once, while the Enterprise received minor splinter damage from numerous near misses. The rest of the German force safely made port.

The Germans fired 34 torpedoes from impossibly long ranges in eight separate attacks, but in rough conditions with extended visibility the better gun platform prevailed. The German commander’s decision to divide his flotilla also proved ill-advised as afterward ranges dropped. In the engagement, the Germans lost three ships.

The two British cruisers met up once more and, seeing no further signs of the German squadron and having accounted for three of them at no significant damage to themselves, withdrew toward Plymouth. They arrived on the evening of 29 December, low on both fuel and ammunition. Glasgow had received one hit that killed two crew members and wounded another three, while Enterprise had no real damage except for shell splinters.

The two German survivors, T22 and Z23, reunited and headed towards Saint-Jean-de-Luz near the Spanish border. The rest of the German ships headed back to the Gironde.

Only 283 survivors of the 672 men on the three sunken ships were rescued: 93 from Z27, 100 from T25 and 90 from T26. British and Irish ships, Spanish destroyers and German U-boats took part in the rescue. About 62 survivors were picked up by British minesweepers as prisoners. 168 were rescued by a small Irish steamer, the MV Kerlogue, and four by Spanish destroyers, and they were all interned.

References Koop, Gerhard, and Klaus-Peter Schmolke. German Destroyers of World War II. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2003. O’Hara, Vincent P. The German Fleet at War 1939-1945. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2004

Postscript

On the 26th December eleven German destroyers and torpedo boats sailed into the Bay of Biscay to bring in the blockade-runner “Alsterufer”. however she was sunk by a Liberator bomber of RAF Coastal Command on the 27th, and next day as the German warships return to base they are intercepted by 6in cruisers “Glasgow” and “Enterprise”. Although outnumbered and out-gunned they sank the 5.9in-gunned destroyer “Z-27” and torpedo boats “T-25” and “T-26”.

Regarding the blockade-runner “Alsterufer”….Sunderland aircraft operating from Castle Archdale…201 & 422/423 RCAF also helped in the tracking and took part in several attacks on the ship.

‘Sixty-four survivors were rescued by the cruisers and several more by an Irish steamer, a Spanish destroyer and U-boats.

KERLOGUE, Wexford S.S. Co. Built in Holland in 1938 for the Wexford S.S. Co. In 1957 the KERLOGUE was sold to Norwegian interests and wrecked in 1960 off Tromso.”

All Irish ships leaving Ireland had to call at Fishguard to obtain a British Navicert before proceeding and likewise when returning to Ireland. In the early hours of the 29 December 1943 when the Irish Vessel Kerlogue was enroute from Lisbon a Focke Wulf 200 circled and signalled ” SOS follow” the ship picked up 168 survivors from the encounter with HMS Glasgow and HMS Enterprise. The little ship with a crew of 12 under Capt Donohue set course for Ireland direct. The senior German officer Kplt. Quedenfeldt requested that they be taken to Brest but he refused. They Irish crew could have been easily overpowered but the refusal was accepted. Despite repeated requests by Lands End radio, to proceed to Fishguard they continued to Ireland and landed the survivors there. They were interned. The Irish captain was at the receiving end of a very abusive Naval officer when he next called to Fishguard, who threatened to have him interned for his humanitarian act.

Bay of Biscay Offensive (February-August 1943)

Major anti-U-boat operation conducted by the British and U. S. air forces. Beginning in January 1942, Allied maritime patrol aircraft carried out air antisubmarine transit patrols in the Bay of Biscay. The advent of the new 10-cm radar in late 1942 and new methods of operations research encouraged a fresh approach to the flagging campaign there. The revised concept foresaw a continuous barrier patrol of the U-boat transit exit routes from the Bay of Biscay into the Atlantic by a total of 260 aircraft equipped with brand-new ASV Mk. III 10-cm-band radars. Operational command would lie with the Number 19 Group of the Royal Air Force’s Coastal Command. Allied projections for success were vague and excessively optimistic, but the planners assumed correctly that it would take the Germans at least four months to respond effectively to the new 10-cm radar.

The actual offensive was preceded by three trial phases: Operations GONDOLA (February 4-16, 1943), ENCLOSE I (March 20-28, 1943), and ENCLOSE II (April 5-13, 1943). Beset by difficulties, such as the withdrawal of the U. S. Army Air Force’s B-24 Liberator bombers, slow delivery of the ASV Mk. III radar, and lack of aircraft, the operations were nonetheless a success in that they demonstrated an increased efficiency in aircraft allocation and in U-boat sightings.

Air Marshal Sir John C. Slessor, head of Coastal Command, decided to launch the full-scale offensive (Operation DERANGE ) on April 13 with 131 aircraft. The repeated, accurate night attacks by the Vickers Wellington medium bombers of Number 172 Squadron, then the only Coastal Command aircraft equipped with new ASV Mk. III radars and Leigh lights, produced instant, although unforeseen, results. The failure of the German threat receivers to warn the U-boats of the incoming aircraft and the success of two U-boats in shooting down the attacking planes convinced the German U-boat command that the remedy was to give up the night surface transit and to order the U-boats to fight it out with aircraft while on the surface during daylight hours.

Coastal Command aircraft wreaked havoc among the grossly overmatched U-boats during those daylight battles. In May alone, six U-boats were destroyed and seven so severely damaged that they had to return to their bases. In turn, the U-boats accounted for only 5 of 21 aircraft lost by the Coastal Command in the Bay of Biscay that month.

The German withdrawal from the North Atlantic convoy routes following the “Black May” of 1943 allowed Slessor to step up the operation with additional air assets. The Germans took to sending the U-boats in groups in order to provide better antiaircraft defense, yet in June, four U-boats were lost and six others severely damaged. DERANGE peaked in July, when Allied aircraft claimed 16 U-boats- among them three valuable Type XIV U-tankers-compelling Grossadmiral (grand admiral) Karl Dönitz to call off a planned operation in the western Atlantic.

German losses in the Bay of Biscay dropped considerably thereafter, but the air patrols remained a formidable obstacle throughout the remainder of the war by forcing the U-boats to stay submerged for most of the time during transit. Although the Battle of the Atlantic was ultimately won around the convoys, the Bay of Biscay Offensive contributed to the success by preventing many U-boats from reaching their operational areas in time to saturate convoy defenses as they had done in March 1943.

References Blair, Clay. Hitler’s U-Boat War. Vol. 2, The Hunted, 1942-1945. New York: Random House, 1998. Gannon, Michael. Black May. New York: HarperCollins, 1998. Morison, Samuel Eliot. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Vol. 10, The Atlantic Battle Won, May 1943-May 1945. Boston: Little, Brown, 1956. Roskill, Stephen W. The War at Sea, 1939-1945. Vols. 2 and 3. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1957 and 1960