22/23 October 1943

The English Channel’s importance as a transit route for British and German shipping made it one of the war’s most bitterly contested bodies of water. When the blockade runner Münsterland and its escort of six minesweepers and two patrol boats departed Brest on October 22, 1943, the Royal Navy’s Plymouth Command ordered the antiaircraft light cruiser Charybdis (senior officer, Captain G. A. W. Voelcker); the fleet destroyers Grenville and Rocket; and the escort destroyers Limbourne, Wensleydale, Talybont, and Stevenstone to intercept the German convoy. Because Plymouth was a transit point, it often tried to maximize resources by using ships that were passing through, such as the Charybdis, but this practice had its dangers, as became clear in execution.

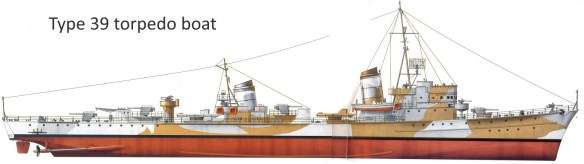

The British warships arrived off the Breton coast shortly after midnight on October 23 and, with the cruiser in the lead, began sweeping west. Meanwhile, the German 4th Torpedo Boat Flotilla, T23 (Korvettenkapitän Franz Kohlauf ), T26, T27, T22, and T25 reinforced the escort. Based on past operations, the Germans had a good idea when and how the British would come. When T25’s hydrophone detected ships to the northeast, the 4th Flotilla turned toward the contact.

At 1:30 a. m., the Charybdis’s radar detected the Germans 14,000 yards ahead. As the columns rapidly converged, Captain Voelcker ordered his column to come to starboard and increase speed, but there was confusion and only the rear ship received his signal. A minute later at 1:43 a. m., the German commander saw the cruiser’s large silhouette illuminated against the lighter northern horizon only 2,200 yards distant. He ordered an emergency turn to starboard. As they came about, the T23 and then T26 emptied their torpedo tubes toward the enemy.

British radar was registering contacts and the British were intercepting German radio traffic. The Charybdis fired star shell, but the rockets burst above the clouds and only brightened the overcast sky. The Limbourne, which had lost touch with the flagship, plotted a contact off its port bow and, unsure whether it was hostile, likewise fired rockets. The fleet destroyers came to port and crossed ahead of Limbourne. Then lookouts aboard the Charybdis reported the tracks of torpedoes.

The cruiser came hard to port, but at 1:47 a. m., a torpedo struck it on the port side. As this happened, the German column was still turning and both the T27 and T22 fired full torpedo salvos as they came about. Only the T25 failed to launch. At 1:51 a. m., the German column withdrew on an easterly heading.

Another torpedo struck the Charybdis, and within five minutes its deck was under water. A minute later, a torpedo slammed into the Limbourne and detonated the small destroyer’s forward magazine. The Grenville and Wensleydale barely avoided the massive explosion. The Charybdis sank at 2:30 a. m. Attempts to tow the Limbourne failed and it was scuttled.

The British force was an improvised one following a scripted plan and had blundered into a massed, close-range torpedo salvo. The British were fortunate in that they only lost two ships. Admiralty staff studied the action off Les Sept Iles intensely and drew many of the right conclusions. Not coincidentally, it was the last clear victory German surface forces would win during the war.

References Smith, Peter C. Hold the Narrow Sea, Naval Warfare in the English Channel 1939-1945. Ashbourne, UK: Moorland, 1984. Whitley, M. J. German Destroyers of World War Two. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1991

Blockade Running

In the early stage of World War II, the main lines of communication between the Axis powers were either over land via the Trans-Siberian Railway or, when Japan entered the war in December 1941, across the sea by surface blockade runners. Japan used German blockade runners to send such goods as rubber, cooking oil, lead, tin, and tea to Germany. In return, the ships carried industrial products such as locomotives and machinery and various pieces of technical equipment, scientific instruments, and chemical and pharmaceutical products to Japan. In addition, ships carried supplies and spare parts for German warships in the Far East. Some blockade runners also supplied German armed merchant cruisers operating in the South Atlantic, Indian Ocean, and Pacific.

After Germany invaded the Soviet Union (Operation BARBAROSSA ) in June 1941, the continental line was cut, and only sea routes remained. Blockade running that began in April 1941 and ended in October 1943 involved a total of 36 ships traveling from Asia to Europe. Six of them were recalled or returned after sustaining damage, and, of the 30 that remained, 11 were sunk by Allied forces or were scuttled by their own crews to prevent capture. Another 2 were accidentally sunk by German submarines, and 1 was seized by a U. S. cruiser. Thus, 16 ships actually completed their voyages and delivered their cargo to the port of Bordeaux in German-occupied France.

In the other direction, 23 ships, including 5 fleet supply ships, were sent from Europe to the Far East between September 1941 and April 1943. Of these, 16 reached Asian ports, 5 were sunk or scuttled, and 2 were recalled or returned to port.

Overall, 45.8 percent of the blockade runners on the Far East route were lost. However, annual ship losses rose dramatically over the course of the war. Between April 1941 and October 1942, only 12.1 percent were lost, whereas in 1943, losses rose to 85.7 percent. Of 104,700 tons of materials loaded on the ships, only 26,600 tons reached their destinations. In addition to raw materials and equipment, these ships also transported passengers. Some 900 passengers embarked to travel from the Far East to Europe, but fewer than half of them arrived safely. A total of 136 died when their ships were sunk, and the remainder became prisoners of war or remained in the Far East after their ships turned back.

From early 1944, submarines took over the blockade runners’ mission. Between then and early March 1945, 16 German U-boats sailed to the Far East as combat cargo transporters. But only 8 actually arrived in Far Eastern ports, carrying some 930 tons of cargo. The other 8 boats were lost, most of them to hostile action. Through the end of 1944, only 3 submarines reached Europe, but none got to Germany: the U-843 arrived at Norway but was sunk in the Kattegat Straits; the U-510 and U-861 reached French ports.

Under the code name AQUILA, 5 Italian submarines also participated in blockade running. Departing France, they carried some 500 tons of supplies for German/ Italian submarine bases in the Far East as well as personnel and cargo for Japan. None of them returned to Europe. The Japanese also sent five submarines to Europe to transport German military technology and to exchange personnel. Ultimately, four of them reached the Continent, but only three returned: two to Singapore and one to Japan. All these submarines had Japanese and German technicians, liaison officers, and equipment and blueprints of German’s newest weapons. Of 89 passengers aboard Axis submarines traveling from Japan, 74 arrived in France; the remainder died when their boats were sunk. A total of 96 passengers sailed in the opposite direction, 64 of them arriving safely; 22 were lost while under way, and 10 others fell into U. S. hands.

References Boyd, Carl, and Yoshida Akihiko. The Japanese Submarine Force and World War II. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2002. Krug, Hans J., and Yoichi Hirama. Reluctant Allies: German-Japanese Naval Relations in World War II. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2002.