It had not originally been intended that the British should be responsible for securing Basra. When planning began at Central Command for Operation Iraqi Freedom in the spring of 2002, the only task allotted the British, and that to 3 Commando Brigade, was the seizure of the Fao peninsula by amphibious assault, while other British forces participated in the drive north to Baghdad. While the Americans wanted the British to participate, their military participation, as opposed to their presence for political reasons, was not judged essential. It was thought, probably correctly, that the United States had sufficient available force to liberate Iraq without allied assistance. By June, however, the plan changed. The moving force seems to have been General David McKiernan, nominated as the general commander (CFLCC – Combined Force Land Component Commander), who knew the British well from his involvement with NATO’s Allied Rapid Reaction Corps (ARRC) in Germany, liked them and was liked in return. He now offered the British not only a part in but control of operations in northern Iraq, through the ARRC, which has a British commander.

His proposal then encountered political objections. The northern operation, to include not only the British but also the American 4th Infantry Division, could only be mounted with the consent of the Turkish government, which would have to approve its transit from Mediterranean ports and airfields to and across the Iraqi border. Even before the Turks began to make general difficulties, they were expressing particular objection to admitting British troops to their territory. The Americans found the Turkish attitude difficult to understand. The British planners involved, through consultation with the Foreign Office, were able to offer what seemed a persuasive explanation. The Turks are deeply sensitive to British involvement in their internal affairs. In 1919, after the First World War, in which they had been enemies, the British installed an army of occupation in western Turkey, the Army of the Black Sea. It had only been removed by armed confrontation. Throughout their administration of the League of Nations mandate for Iraq, the British had managed the affairs of Iraqi Kurdistan in a manner the Turks found hostile to their national interest. Most important, in 1932, the British had argued for and successfully achieved the award of the Mosul region, with its rich oil fields, to its client kingdom of Iraq by the Treaty of Lausanne. Turkey’s attitude in 2002 may have been tit-for-tat. It may have expressed some deeper-seated suspicion of British motives. Whatever the explanation, the Turks were immovable. Even before they had made it clear that they would not allow American troops to traverse their territory, they had definitively excluded any British. As a result, an alternative front of operation for the British complement had to be found. On 28 December 2002, the British told the Americans that they would deploy the bulk of their forces to Kuwait and take part in operations in the south.

That left time short. While the political crisis between Saddam and the West dragged out, with the Iraqis seeking to demonstrate that there was no justification for the taking of military measures against them, and with the Americans and British insisting the opposite, planning at Central Command went on. British planning had suddenly to accelerate. Though no deadline had yet been set, it was prudent to suppose that an invasion of Iraq would occur, without a satisfactory political settlement, by early spring. The Americans were speaking of March. That left only ten weeks for a deployment, a far shorter period than had been available before the First Gulf War of 1991. Fortunately there had been an extended exercise in Oman earlier in 2002, which had revealed certain necessary measures to be taken, including that to ‘desertize’ the Challenger tanks. The exercise had also left one of the units of 3 Commando Brigade in the area. Hastily the Ministry of Defence began to reinforce, sending ships and aircraft and speeding the dispatch of ground forces. Ever since the Falklands crisis of 1982, when Britain had had to assemble a long-range expeditionary force at a few days’ notice, the planning organization had been honing its skills of improvisation. Now, in a hurry, another Commando was sent out to join its sister unit; 16 Air Assault Brigade, which was not encumbered by armour requiring heavy lift, was despatched, and 7 Armoured Brigade, the most experienced and readily deployable major formation on hand, was shipped from Germany. By February Britain had the makings of a respectable intervention force in place. No other European country could have achieved the same results in the time available, not the French and certainly not the Germans. British troops, though few in number and less technically advanced than the American, had once again demonstrated their formidable readiness to respond to a challenge and competence to meet it.

Their competence was particularly suited to the problems presented by the need to isolate, enter and subdue the resistance in Basra. The British cannot match the Americans at the highest level of modern military performance. Shortage of funds deprives them of state-of-the-art equipment in the fields of target acquisition, reconnaissance, surveillance and intercommunication. In certain military tasks, however, they are without equal. Special operations is one, as American emulation of the SAS demonstrates. Counter-insurgency is another. Thirty years of engagement with the Irish Republican Army, in the grimy streets of Northern Ireland’s cities, has taught the British, down to the level of the youngest soldier, the essential skills of personal survival in the environment of urban warfare and of dominance over those who wage it. Every man covering another on patrol, watching the upper window, skirting the suspicious vehicle, stopping to question the solitary male: these are the methods the British army knows backwards. Painfully acquired, they have resulted in a superb mastery of the technique of control of the streets. The army has created an artificial urban training ground where these skills can be taught. As a result they have become expert at reading the geography of an urban area – which are the likely ambush points, where bombs are likely to be planted, what observation point must be entered and occupied – and have used their mastery of urban geography to dominate. Irish Republicans hate those they call ‘Crown forces’ for their professionalism, since it has blocked their ambition to control the Northern Irish cities themselves. As the entry into Basra was to prove, the British army’s mastery of the methods of urban warfare is transferable. What had worked in Belfast could be made to work also in Basra, against another set of urban terrorists, with a different motivation from the Irish Republican though equally as nasty.

Basra’s inhabitants occupy an area about two kilometres (1.24 miles) square, with a sprawl of suburbs on the southern side. The eastern boundary of the built-up area is formed by the Shatt el-Arab, the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates. The old city, a warren of narrow streets, is not, however, on the water. The modern city has grown up to enclose it. There are a number of tall buildings but they are few and scattered; nothing in Basra resembles the government quarter in Baghdad, with its complex of towers and ultra-modern buildings. It is a shabby, traditional Middle Eastern town, overgrown by the influx of population and bewildering to an outsider who does not know its street pattern at first hand.

Fortunately, in the years since the First Gulf War, the British intelligence services had done a great deal to set up a comprehensive network in Basra, in the expectation that, if trouble with Saddam continued, the largest concentration of Shi’a in the country could be turned against him; it would certainly yield useful information if properly exploited. It was greatly to the advantage of the British that, despite their withdrawal from empire in the 1960s and ’70s, they had never fully lost touch with the region. Their long association with the Indian subcontinent and with the Gulf principalities provided a bedrock of familiarity with the political and ethnic realities; their commercial involvement in Iraq, particularly through the oil industry, sustained personal contacts; and the British services’ provision of equipment and training programmes to the Gulf principalities’ armed forces kept in being a body of local experts who knew the terrain and the tribes and, above all, spoke the local language. Knowledge of Arabic was a not uncommon language skill in the British army, particularly in its Special Forces and Intelligence Corps.

After the British parted company with the US Marine Corps on 23 March, their conventional ground forces were quite well prepared to undertake the isolation and capture of Basra; 7 Armoured Brigade took over the positions vacated by the 7th Marine Regiment, 16 Air Assault Brigade those of 5th Marines. They did not, however, immediately close up to the city, but remained at a distance, forming a cordon outside the built-up area to put it under surveillance, prevent the passage of reinforcements into the city and monitor the inhabitants leaving. Each flank of the cordon rested on the river, the opposite bank of which was held by 3 Commando Brigade, while the cordon itself, about twenty miles long in circuit and crossing all the roads into the city on the west bank, was maintained at a distance of about two miles from the outskirts. The plan formed by Major General Robin Brims, the 1st (UK) Armoured Division commander, was at first to wait and watch and to gather as much information as possible from fugitives about points of resistance, whereabouts of armed bodies of fighters and the identity of leaders, military and political. Despite the efforts of the Ba’ath organization to control the population, fugitives soon began to trickle out, progressively in larger and larger groups. They sought safety, but also food and water, and were ready to talk to the British, who spread the word by mouth and printed leaflet that they had come to stay, would protect civilians and could be trusted. Meanwhile SAS and SBS teams penetrated the built-up area under cover, to reconnoitre and make touch with intelligence contacts in the city.

General Brims was resolved not to provoke a fight for the city until he was certain that it could be won quickly and easily, without causing serious damage or heavy loss of life, particularly civilian life. The policy was particularly necessary in view of the hostile attitude of much of the British media, the BBC foremost, to the war against Saddam; unlike their American counterparts, who generally supported the war and their President, home-based British journalists – not those travelling with the troops – regarded it as a neo-colonialist undertaking, doubted official justifications for its launch, particularly that Saddam possessed weapons of mass destruction, and were eager to report anything that smacked of atrocity. Ali Hassan al-Majid, ‘Chemical Ali’, the senior Ba’athist in the city, was for his part anxious to keep the population within the city bounds and hoped to provoke a bout of street fighting in the narrow byways that would feed Western media prejudice. He also hoped that the British forces would suffer heavy casualties, with a consequently bad effect on British public opinion at home.

‘Chemical Ali’s’ capacity to achieve the effects he desired was, however, severely limited by the means available to him. He was personally intensely unpopular with the Shi’a population, which he had slaughtered in large numbers after the Basra uprising of 1991. His Ba’ath party organization was thinly spread in a city where it had always been regarded as an instrument of Sunni dominance. He had, finally, only the sketchiest military apparatus with which to operate. The 11th Division, the local formation of Iraq’s so-called regular army, had already largely dissolved. Those soldiers who remained could be made to fight only by terror methods, which provoked farther desertions. As a result, those who would do his will were either local Ba’athists, all too aware of the fate that awaited them if the fight for the city was lost, and fedayeen sent from Baghdad by Qusay Hussein, Saddam’s son. Many were foreigners; few had any training beyond a sketchy course in firing the Kalashnikov assault rifle and the RPG-7 grenade launcher. Of the skills at which the British infantry excelled – marksmanship, mutual support and massing firepower when attacked – they had no knowledge whatsoever.

Between 23 and 31 March the siege of Basra took the form of a stand-off, with ‘Chemical Ali’ trying to tempt the British inside and the British refusing to move major units downtown. They waited and watched, gathering intelligence and interrogating fugitives. Small units infiltrated the city, SAS and Royal Marine Commando SBS teams, patrols from the regular units and individual snipers, who chose fire positions and observed. The Iraqis tried to provoke a fight, by launching sorties with tanks and armoured vehicles and by mortaring the British lines. Sometimes they overreached themselves. On the night of 26–27 March a column of Iraqi tanks headed out into open country. At daylight it was intercepted by the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards, who destroyed all fifteen tanks at no loss to themselves. The Iraqi tanks involved were Soviet T-55s, when built after the Second World War excellent fighting vehicles but, by the twenty-first century, museum pieces. The British Challengers, with their 120mm guns, could destroy them at ranges too great for their own guns to reach.

By 31 March the British were becoming more aggressive. General Brims decided that his intelligence picture was sufficiently clear for him to begin infiltrating larger units into the city. One task given them was to attack Ba’ath party leaders, whom snipers were able to identify by their habit of using cell phones on the streets and visibly issuing orders to people around them. Engaging at several hundred yards, with an updated version of the bolt-action Lee-Enfield rifle, in use in the British army for over a century, they achieved a dominant psychological effect. Major Ben Farrell, a company commander in 1st Irish Guards, described the technique to The Daily Telegraph: ‘Our snipers are working in pairs’ (one man used the rifle, the other a telescope), ‘infiltrating the enemy’s territory to give us very good observation of what is going on inside Basra and to shoot the enemy as well when the opportunity arises.… They don’t kill large numbers but the psychological effect and the denial of freedom of movement to the enemy is vast.’ An Irish Guards sniper later described to a Daily Telegraph reporter how their missions worked. ‘It’s a bit scary going into buildings because they haven’t been cleared and we don’t know if they have left any booby-traps for us. But once we are here they don’t know where we are and it feels OK. We can report back what is going on – to call in air strikes or direct artillery – and if they are within range of our rifles we will shoot them.’

This sort of operation – targeting armed terrorists acting singly or in small groups, without causing harm to the civilian population – is one at which British troops excel. They have learnt the skills in many terrorist-ridden environments, including Beirut and Sierra Leone as well as Northern Ireland, over the last thirty years and more.

British technique paid off in Basra, in what could be viewed as a repetition of the success of Operation Motorman against the Irish Republican Army in Londonderry in 1972. There the IRA had seized control of a large area of the city, proclaimed it to be ‘Free Derry’ and denied entry to the security forces. Anxious to avoid both the widening of disorder and a bad press, the army did not intervene. Over several months, however, it constructed a detailed intelligence plot and secretly rehearsed a plan to retake ‘Free Derry’ without provoking a costly fight in the narrow streets. When ready, it struck. Early one morning, columns of military vehicles penetrated ‘Free Derry’ from several directions simultaneously and within a few hours had reoccupied the whole area and re-imposed civil order, without provoking armed resistance. Motorman was the indirect inspiration of the operation to take Basra.

Because Basra is much larger than Londonderry, with a far greater population, its capture could not be staged as a single coup. Having assembled an intelligence picture of where the Ba’ath power structure was located and how it worked, 1st (UK) Armoured Division began in early April to launch raids into the city, down the main roads leading into it, by columns of Warrior fighting vehicles. The Warrior is well adapted to such tasks. Relatively well-armoured and well-armed, with a 30mm cannon in its turret, and capable of speeds of 50 miles per hour or more, the Warrior has the capacity to make quick penetrations of a position and speedy withdrawals. For several days the Warriors raided in and out, destroying identified Ba’athist positions and adding to the divisional staff’s stock of intelligence. Such intelligence, amplified by information gathered by the SAS, SBS and Secret Intelligence Service teams, allowed point attacks to be launched by artillery outside the city and by the coalition air forces. Among the successes achieved was the destruction of a building in which the Basra Ba’ath leadership was meeting, causing many fatalities, and another attack on what was believed to be the headquarters of ‘Chemical Ali’ on 5 April. It was later found to have been based on false intelligence but it was for a time believed by the population to have been successful and so helped to weaken Ba’athist control.

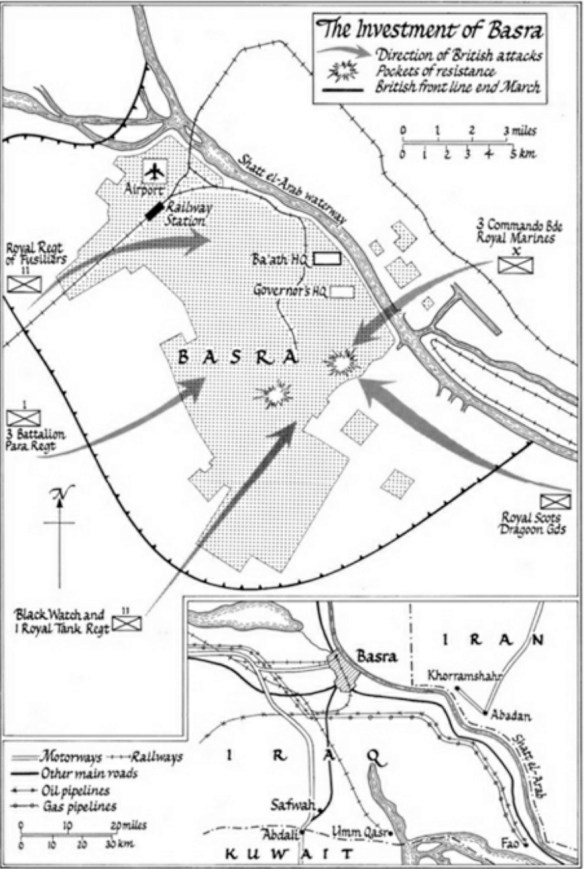

Finally, on 6 April, General Brims launched a full-scale assault. The city was now ringed with British units, the 1st Royal Regiment of Fusiliers to the northwest, the 3rd Battalion Parachute Regiment to the west, the Black Watch with the 1st Royal Tank Regiment to the southwest, the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards to the south and the Royal Marines across the river, but with amphibious capability, to the east. The original plan was that, after the units had launched simultaneous but individual drives down the streets leading to the centre, they should withdraw and wait the night outside before repeating the procedure. The initial penetration, however, went better than expected: in an uninhabited factory complex, where there was no risk of causing civilian casualties, it proved possible to call in helicopter gunship strikes directed by Air-Naval-Gunfire Company (ANGLICO) liaison teams of US Marines allotted to the British armoured division. The firepower deployed inflicted heavy losses on Ba’athists and fedayeen defending the complex.

Such was the early success achieved by his forces that General Brims decided to persist. They were organized in ‘battle groups’, an improvised formation much favoured by the British and viable in a small army where everyone knows everyone else. General Brims’s battle groups consisted typically of one or two companies of infantry mounted in Warrior armoured vehicles and a squadron of Challenger tanks. One battle group, which had cleared out the factory complex, was switched to attack the area of the College of Literature, a university campus occupied by 300 fedayeen, mostly non-Iraqi Islamic terrorists from other Arab countries, including Morocco, Algeria and Syria. Reducing the resistance of the fedayeen, who lacked military skills but were eager to fight to the last, took four hours, in a battle in which the British troops could not call on fire support, because of the danger of causing civilian casualties, but had to depend on their own infantry skills.

By the evening of 6 April the British were largely in control of Basra and 7 Armoured Brigade, the core of 1st (UK) Armoured Division, set up its headquarters on the university campus. The next morning, 7 April, 16 Air Assault Brigade, with two parachute battalions and the 1st Royal Irish Regiment under command, entered the narrow streets of the old city where armoured vehicles could operate only with difficulty, and set about chasing the remnants of the Ba’ath and the fedayeen out of the area. It proved that there was little to do. Saddam’s régime recognized that it was beaten and its representatives were leaving the city.

On 8 April the British began to adopt a postwar mode. Anxious to reassure the Shi’a population that they had come to stay, they took off their helmets and flak jackets, dismounted from their armoured vehicles and began to mingle with the crowds. Soon afterwards General Brims withdrew his armoured vehicles from the city centre altogether, leaving his soldiers to patrol on foot, with orders to smile, chat and restore the appearance of normality. It was an acknowledgement that the war in the south was over. The struggle to win ‘hearts and minds’ – a concept familiar to British soldiers in fifty years of disengagement from distant and foreign lands – was about to begin.

The British campaign had been an undoubted success. They had secured all their objectives – the Fao peninsula, the Shatt el-Arab, the oil terminals, Iraq’s second city – quickly and at minimal cost. British loss of life was slight. They had also conducted their war in a fashion that appeared to leave them, as the representatives of the coalition, on good terms with the southern population of defeated Iraq. The inhabitants of Basra made it clear, to the British soldiers who took possession of their city, that they were glad to be rid both of the representatives of Saddam’s régime and of the foreign fighters who supported it. If a new Iraq were to be created from the ruins of the old, Basra seemed the most promising point at which to start.